The AI Sham Continues

Anthropic's "Constitutional AI" is just more lipstick on a pig

Image by author using photoshop - the robot head is ironically sourced from craiyon.com

As the criticisms and lawsuits about publicly released AI programs1 have been piling up, companies and investors have begun working to distance themselves from the thieving dumpster fire that most of these “products” actually are, whether by legal manipulation, marketing deception, or full-blown flight.

AI as a wide scale commercial product has been the greatest technology-based fraud on mankind of all time, and all but the most starry-eyed fans know it. The question is, when will society take control of the problem and hold its perpetrators accountable?

The core issue is not specifically which law was broken, though plenty have, despite the legal system’s woeful inadequacies. It is about co-opting culture, and profiting from it, at the expense of those who actually created it. To use the words of a Professor of Innovation at IE Business School and popular writer on Medium, Enrique Dans, who was strenuously arguing against this very point:

it is about isolating [culture], degrading it, and preventing it from being able to feed future evolution, to be the basis for new creations.

Generative AI is a scam

The very definition of generative AI is a lie—at least as it pertains to most publicly released, for-profit products:

A type of AI that can create new content like conversations, stories, images, videos, and music. It can learn about different topics such as languages, programming, art, science, and more, and use this knowledge to solve new problems.

Generative AI does not ‘create new content’ by its very nature. The reason there are hundreds of lawsuits in multiple countries against practically every AI developer is because the foundational element of its development requires the theft of vast troves of human output.

If it was indeed intelligent, it could function well on limited instruction and craft original work of its own accord—the same way humans do. But it cannot. It “synthesizes” oceans of content created by humans without any of the context, experience, emotion, or intelligence. And, most importantly, without any of the credit or benefit going to those who put the work in before.

Here’s a cogent description of how Meta treated copyright and privacy law in building its AI, which is quite similar to the modus operandi of every other AI company (edited slightly for clarity; links added that substantiate the claims made):

When [Meta developers] went to [book publisher] Harper Collins and they went to these other people who had archives of books, they realized it was going to be a big pain in the butt to license everything and it was going to cost them money. So, according to their internal leak documents, which have already come out in other court proceedings, they said that they would rather just pirate the materials. They even used the word pirate and they talked about how this was probably illegal, and that they were exposing themselves to risk. So, they directly sought authorization from Mark Zuckerberg himself. [Who allegedly gave it].

Even after taking huge amounts of copyrighted or otherwise protected material for training, generative AI does not produce “new content.” That is, unless you count the abundance of nonsense—quaintly called ‘hallucinations’ by some—that sane people would simply not waste time creating. AI companies have claimed that work generated by their products are derivative, but not identical. Still, the lack of perfect parallel does not obviate plagiarism or legal infringement.

Moreover, even arguably ‘new’ stuff produced by AI is severely problematic.

About a year ago, the Dudesy podcast was forced into submission by the estate of late comedian George Carlin. The company had the nerve to create an hour-long special featuring an AI version of Carlin, without permission from anyone. Chris Williams, from Above the Law, described the opening of the show:

The special begins with a disclaimer that paints the AI venture as no different than a human comedian doing an impression of a famous comedian. And, after repeatedly saying that they are NOT George Carlin, they begin the set by inviting the viewer to give a warm welcome to George Carlin. Pick a battle, dude.

AI companies have been pulling a similar stunt with art. Without permission, they promote their AI’s ability to mimic specific artists’ style by using those artists’ names. Some observers have even identified the tattered remnants of artists’ own signatures on “new” images created by AI programs. Others worry about images being generated in their distinct style (or name) that they themselves would “never make,” which could cause harm to their brand or to society generally.

It has less to do with what AI produces that has confounded the legal system than the way in which AI stores and uses protected material. Obviously, if an image contains identifiable pieces of another work—such as the signature—it should hardly be a question whether a violation occurred (although even this has not uniformly persuaded courts). But most AI models do not store whole works, they instead tokenize them and store the tokens.

They basically break a work down into tiny pieces and assign each a mathematical value, or token. To identify a “style,” for example, the component pieces are treated the same way as words are in LLMs—they function on probabilities and patterns. Basically, the AI guesses what token would likely follow a previous one. The tokens might be selected from the specifics of a user prompt or from their association to other tokens.

As two professors writing on the subject noted:

When AI learns about Miyazaki’s work, it’s not storing actual Studio Ghibli frames (though image generators may sometimes produce close imitations of input images). Instead, it’s encoding “Ghibli-ness” as a mathematical pattern – a style that can be applied to new images.

Whether copying styles is infringement remains in question. Returning to Dans, he claimed:

If the system does not literally copy, reproduce, or distribute the original content, there can be no infringement.

This may be the direction courts take on copyright cases related to AI, but it is a fundamentally flawed approach. Or, at a minimum, the law has failed us. Many who hold views like Dans’ miss the very purpose behind protecting intellectual property, whether courts or AI enthusiasts or companies. A commentor on Dans’ article concisely identified the issue:

[AI] allows to “scale” [the] intellectual part which [creates] asymmetry between effort and result… Intellectual property laws were created to protect investment.

In a paper on the philosophy behind the objections to AI-generated creative works, Trystan S. Goetze from Cornell University wrote:

There are established expectations for who is permitted to take which kind of information from us without explicit permission, and who is required to ask. In creative contexts, there are permissive norms of sharing artworks, and established expectations that other human beings will draw upon these for developing their own skills and for inspiration in creating original or derivative works. But there is no such established norm for the mass appropriation of such works for the purposes of creating text-to-image AI models. The lack of such an information norm means that explicit consent is required in the case of AI development, but not in the case of human artistic practice.

In short, AI companies should be required to ask for permission to include others’ works in their training sets, a request for which creators can—and should—demand compensation or credit. And this should not be the currently in vogue, twisted version of permission—the ever-insidious ‘opt out.’ This is when permission is assumed unless a creator actively takes steps to deny it.

Given the purely profit-driven business models that virtually all generative AI follow, the companies behind them should be liable for failing to get explicit permission while profiting from their crime. Kids get tossed out of school for committing plagiarism. How is this any different?

Moreover, plagiarism cases have gone to court in the past, with the violators often paying court-ordered restitution or settlements. Some high-profile figures have lost prominent jobs. Plagiarism cases can invoke various civil and even criminal statutes, some of which do not require a “literal copy.”

Edvard Munch, 1893, The Scream (public domain)

This isn’t some kind of Technophobia

Instead of addressing the matter at hand, apologists will resurrect the ghosts of Luddites, as if the reaction to intellectual theft is merely a fear of new technology. But the fear isn’t for the ability of AI to more swiftly produce. The fear is over what ultimately is produced, and what credit is given to those whose work came before that made the the effort—however minimal it might be for AI—possible.

And so far, we know the answer to both.

In addition to creating “close imitations of input images,” among other likely infringements, AI has already been used in a pathetic attempt to manipulate the 2024 US election, to generate a stupid framework of tariffs, to impersonate celebrities, and to make porn, so one can imagine how it could be used toward other nefarious ends that injures creators (and society).

There is a frighteningly long list of even more messed up things AI has caused or committed, such as when Character.ai’s chatbot allegedly convinced a teenager to kill himself. Or when Microsoft’s Tay.ai chatbot turned into a “sexist, racist monster” within 24 hours of its release. Or when an AI program in the Netherlands caused serious havoc among families:

Parents were branded fraudsters over minor errors such as missing signatures on paperwork, and erroneously forced to pay back tens of thousands of euros given by the government to offset the cost of childcare, with no means of redress.

Or when the Australian government drove three people to suicide and hundreds of thousands into debt, many of whom were wrongly slapped with criminal charges based on faulty AI. Or when landlords engaged in “an unlawful information-sharing” and price-fixing scheme to raise rents, contributing to a growing housing crisis in the US.

One could write a series of books on the tragedies inflicted by shitty AI promoted by these fraudulent companies. That alone should have been enough to put the brakes on its distribution and profitability. But greed knows no ethical bounds.

Just as generative AI does not ‘create new content,’ commercialized AI does not ‘solve new problems.’ Instead, it has made a business out of creating them. And those that have invested in this scam are learning that the hard way, much like they learned of their gullibility during the dot-com bubble.

Source link.

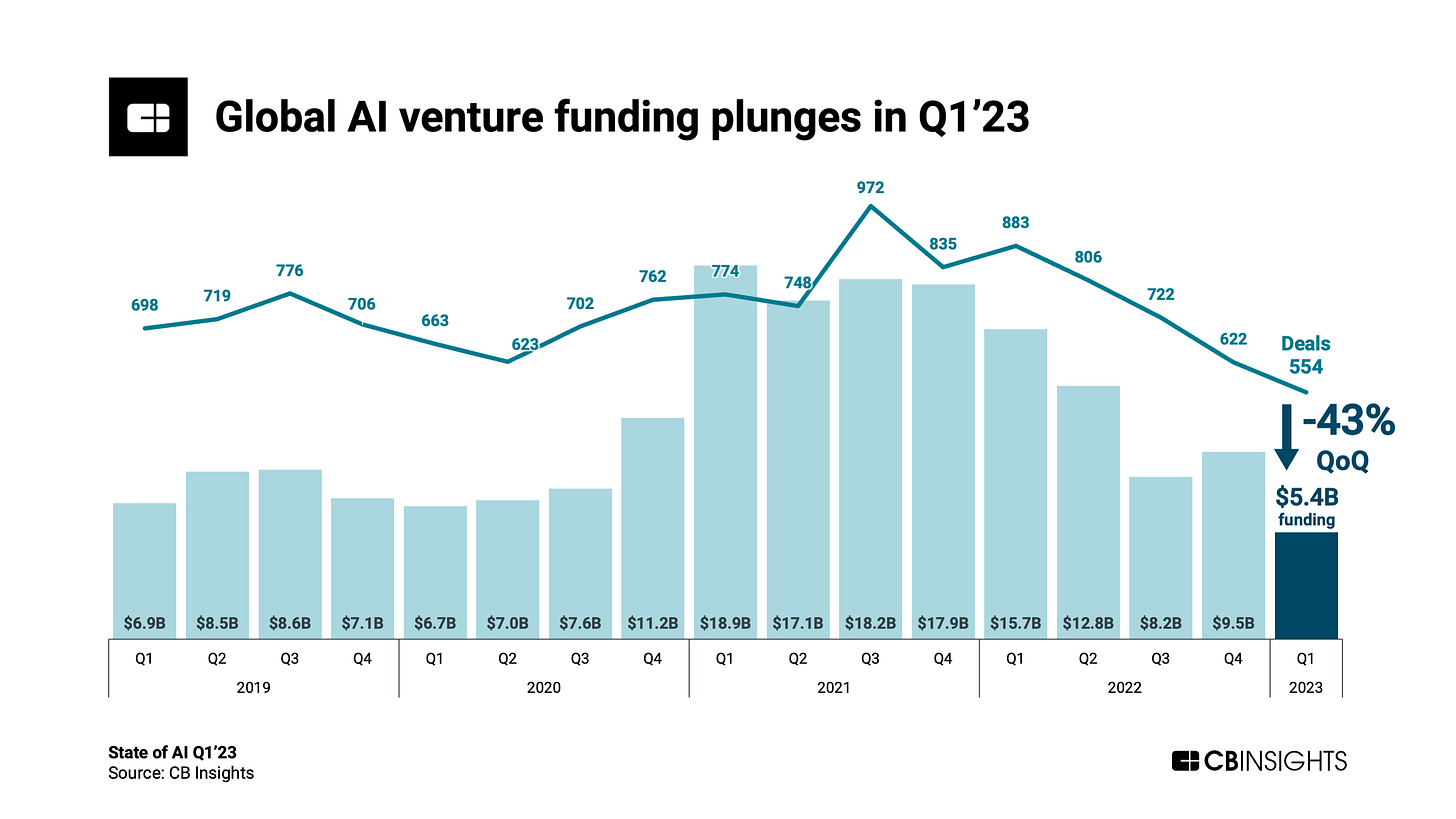

The failed venture

Increasing numbers of companies are scrapping AI projects altogether, with 42% of them reporting having done so in 2024, up from 17% in 2023. Of those desperately clinging to their investments, two-thirds of the 600 businesses asked reported that they have been “unable to transition [their investment] into production.” Researcher John-David Lovelock from Gartner noted:

GenAI is sliding toward the trough of disillusionment, which reflects [Chief Information Officers'] declining expectations for GenAI, but not their spending on this technology.

Perhaps this will change if AI eventually gets better—something that looks increasingly unlikely—but investing in it now or over the past few years is like investing in a toaster that can only toast one side of the bread, and perhaps will only ever toast one side.

Just as there are those who are investing in AI without any demonstrable return, many are now being outed for claiming to have AI in their product or service structure when, in fact, they do not. It’s a phenomenon called “AI washing.”

A report found that in 2019, about 40% of supposed AI startups didn’t incorporate the technology in their business at all. Since then, the US Securities and Exchange Commission began targeting them for fraud. Now, many are reluctant to mention AI as part of their business model, even if they actually use it.

Many companies that did incorporate AI into their infrastructure—typically at the expense of far more capable human employees—have become laughingstocks, lost money, or both, and often try to conceal their failures.

Take Google as an example. During the Olympics, Google ran the so-called "Dear Sydney" ad that tanked so badly it had to pull it. In it, the dad basically tells his daughter that her fan letter to an Olympic star isn’t good enough, so she should use AI to make it better. A writer at TechCrunch wrote that it was "hard to think of anything that communicates heartfelt inspiration less than instructing an AI to tell someone how inspiring they are."

Toys "R" Us ran an ad that made it seem like the company endorsed replacing filmmakers with AI. It resonated about as well as Google’s disastrous commercial, with one comedian writing:

Toys R Us started with the dream of a little boy who wanted to share his imagination with the world. And to show how, we fired our artists and dried Lake Superior using a server farm to generate what that would look like in Stephen King’s nightmares.

Lawyers have humiliated themselves by citing fake, AI-generated precedential cases in court. Companies have been sued for discriminating based on poorly designed AI. Healthcare providers have led patients astray with bad medical advice generated by AI. Drivers of malevolently misnamed “self-driving” cars have faced criminal charges for killing pedestrians while the AI controlled the wheel (even though the driver’s parent company escaped any liability).

MIT professor Daron Acemoglu stated that companies are losing money on AI because they are spending fortunes on it “without understanding what they’re going to do with it.” A study from Boston Consulting Group found that “75% of executives rank AI as a top-three priority… however, only about a quarter of companies are seeing ROI from the investments they’ve made so far.”

In one survey, 20% of companies claimed that they would “deliberately [avoid] AI as a strategic move to differentiate themselves in response to mounting concerns surrounding generative AI.” Whether respondents were being truthful or not, answering that way indicates their fears about the growing public disdain for the incessant wave of AI bullshit.

The Pretenders

Many AI developers have finally come to the realization that vast swaths of the world’s population hold them in visceral contempt for their thievery and subpar products. In an effort to keep riding the gravy train of stolen wealth and cultural degradation, some have tried to paint themselves as moral paragons in an otherwise immoral industry.

Don’t be fooled.

Let’s examine one of the latest: Anthropic.

Anthropic was founded by former OpenAI executives Dario Amodei and Daniela Amodei. The two are siblings. These founders supposedly disliked the corporate direction OpenAI took when it started receiving substantial investments, including over $2 billion from Microsoft.

Dario Amodei described the decision to branch out:

So, there was a group of us within OpenAI, that in the wake of making GPT-2 and GPT-3, had a kind of very strong focus belief in two things. I think even more so than most people there. One was the idea that if you pour more compute into these models, they’ll get better and better and that there’s almost no end to this. I think this is much more widely accepted now. But, you know, I think we were among the first believers in it.

And the second was the idea that you needed something in addition to just scaling the models up, which is alignment or safety. You don’t tell the models what their values are just by pouring more compute into them. And so there were a set of people who believed in those two ideas. We really trusted each other and wanted to work together. And so we went off and started our own company with that idea in mind.

There is a lot that could be unpacked there, but relevant here is the principle of safety. A paper produced by Anthropic team members, which included Dario Amodei, opened with this line:

We would like to train AI systems that remain helpful, honest, and harmless, even as some AI capabilities reach or exceed human-level performance.

They call the principle, “Constitutional AI.”

In that 34-page paper, a version of the word “harm” is used nearly 300 times, and “honest” 15 times. But like virtually every other large language model AI, Anthropic’s privacy policy says very little about harm or honesty and generally suggests that neither is a priority. Its own summary largely dismisses any concerns that would inconvenience the company in its quest for profit:

Our Privacy Policy… includes your right to request a copy of your personal data, and to object to our processing of your personal data or request that it is deleted. We make every effort to respond to such requests. However, please be aware that these rights are limited, and that the process by which we may need to action your requests regarding our training dataset are complex. [Emphasis added].

In its more detailed policy, the company explicitly states that it collects data “through commercial agreements with third party businesses.” This phraseology has been a boon to every data thief in the United States, including those who (sometimes, at least) operate as legitimate companies.

While third-party brokers might violate the law to acquire data, purchasers (i.e. AI companies) can claim a layer of protection from liability because of the veneer of legitimacy provided by these so-called “commercial agreements.” This is because the US government has taken virtually no steps toward codifying privacy or data protection, and the latest administration has obliterated the miniscule efforts undertaken by the previous one, as detailed here:

Added to Anthropic’s vague description of (probably) stolen data dressed up as “commercial agreements with third parties” are the following proclaimed catchall uses. AI companies have staked a significant chunk of their defenses on such provisions:

To provide, maintain and facilitate any products and services offered to you with respect to your Anthropic account, which are governed by our Terms of Service;

To provide, maintain and facilitate optional services and features that enhance platform functionality and user experience;

To improve the Services and conduct research; and

To enforce our Terms of Service and similar terms and agreements, including our Usage Policy.

As I have discussed on both Substack and Medium, Terms of Service have essentially superseded law in many places, but in the United States especially. I noted:

[Terms of Service] effectively strip creators of most of their legal rights while [corporations retain] their own… [ToS claim] substantial rights to a license to creator content, with little guaranteed in return.

These are one-sided “agreements” that put all the power in the hands of multi-billion dollar companies to exploit everyone else for profit. Not only that, but they stand on extremely shaky legal ground under existing contract and other law, but American courts—who adjudicate the largest volume of claims against them—are often too incompetent or too fearful of Big Tech to treat them with objectivity or fairness. (And there is the glaring problem of ‘arbitration clauses,’ but that’s a matter needing far more space to dissect).

It is Gilded Age corruption at a technologically enhanced level, described further here:

Same crap, despite its messaging

Anthropic’s claims of honesty, transparency, and a do-no-harm philosophy ring as hollow as any other. It is no surprise that its founders are progeny of OpenAI. But a class action suit seeks to test part of its purported philosophy in court. On August 19, 2024, three authors filed a class action lawsuit accusing Anthropic of using “pirated copies of their books to train its artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, Claude.”

Classaction.org explains:

According to the filing, the defendant intentionally downloaded hundreds of thousands of copyrighted books from illegal websites and fed unlicensed copies of the works to Claude, all without permission from or compensation to the rightful copyright owners.

This sounds eerily similar to a suit Meta is facing. The article continues:

The complaint claims Anthropic has admitted to training its AI model using the Pile, a dataset that includes a trove of pirated books. A large subsection of the dataset known as Books3 consisted of 196,640 titles downloaded from an infamous “shadow library” site, the case charges.

According to reports, a website called The Eye hosted a dataset of illegally copied books for sale for AI research. These books were kept in a set called Books3, which was part of a larger dataset of mixed content called the Pile. Rights Alliance, a group that represents publishers and authors in Denmark, demanded that the dataset be taken down after discovering works from some of its members.

Anthropic is the latest company accused of acquiring and using hundreds of thousands of works for their own profit without paying for them. For those equating this to taking books out of a library, try going to your local branch and borrowing 100,000 books. If these allegations are proved true, Anthropic should be forced to pay each author for every work that was incorporated into their model—at a minimum.

Meta has been one of the largest users of this dataset and is facing a class action suit of its own as a result. OpenAI is also facing a lawsuit for similar allegations involving a different dataset source.

OpenAI itself is suing Chinese company DeepSeek for… appropriating its content! The English language lacks adequate words to highlight the hypocrisy.

As Lea Frermann and Shaanan Cohney, both of the University of Melbourne, explained, OpenAI is accusing DeepSeek of infringement through a process called model distillation:

Model distillation is a common machine learning technique in which a smaller “student model” is trained on predictions of a larger and more complex “teacher model.”

When completed, the student may be nearly as good as the teacher but will represent the teacher’s knowledge more effectively and compactly.

One has to wonder how the apologists will reconcile this with the complaints of creators should OpenAI win. The company is staking their claim on the notion that this is a violation of their Terms of Service, which Big Tech seems to think supersedes any statute when engaging in its typical chicanery.

Even some political right wingers, who lately have practically advocated for Big Tech to be above the law now that they have thrown their support in the other direction, sued when they saw hits to their own pocket books or reputations, such as they are. Funny how that works.

It has been noted that it may be “impossible” to determine which AI outputs derived from illegally procured books. This may be by design or the result of incompetence. Alex Reisner, from the Atlantic, examined LibGen, one of the databases that provides access to pirated books. Reisner described it this way:

Over the years, the collection has ballooned as contributors piled in more and more pirated work. Initially, most of LibGen was in Russian, but English-language work quickly came to dominate the collection. LibGen has grown so quickly and avoided being shut down by authorities thanks in part to its method of dissemination. Whereas some other libraries are hosted in a single location and require a password to access, LibGen is shared in different versions by different people via peer-to-peer networks…

There are errors throughout. Although I have cleaned up the data in various ways, LibGen is too large and error-strewn to easily fix everything…

Bulk downloading is often done with BitTorrent, the file-sharing protocol popular with pirates for its anonymity, and downloading with BitTorrent typically involves uploading to other users simultaneously. Internal communications show employees saying that Meta did indeed torrent LibGen, which means that Meta could have not only accessed pirated material but also distributed it to others—well established as illegal under copyright law, regardless of what the courts determine about the use of copyrighted material to train generative AI.

One solution is easy. Force AI companies to purchase a copy of every work they use in their training sets, irrespective of whether they can be tied to any specific output.

For those who tend to be critical of creators asserting copyright violations, the question is simple. Why, if this way of procuring data for training sets is so legitimate, are companies going to great pains to evade licensing law or giving credit to those whose works they use? If the answer is ‘cost,’ that itself is a tacit admission to theft.

The ‘safety’ of “Constitutional AI”

Assuming, however, that Anthropic was only referring to what its Claude LLM puts out, rather than whatever morally (or legally) questionable way it acquired its training set, the company’s notion of ‘safety’ leaves a lot to be desired.

Anthropic produced a detailed article titled, “Tracing the thoughts of a large language model.” It revealed the gravest transgression of the rush to distribute AI. It can be distilled to a single statement:

There are limits to what you can learn just by talking to an AI model—after all, humans (even neuroscientists) don't know all the details of how our own brains work.

We don’t know all the details of how our own brains work.

It cannot be anything less than a cardinal sin to create a copy of something dangerous—which humans unquestionably are—without knowing whether the copy will be equally dangerous or even more so, and then releasing it on the public to ‘see what happens.’ That is, at its core, the AI model. And before the apologists go into a huff, this does not mean lethal cyborgs (see above for plenty of non-Terminator examples).

If it is true that AI can learn faster, more efficiently, or just better, than humans, then the invention has already entered perilous territory. This is especially true given that it is learning from humans, and adopting all their worst tendencies. The researchers for Anthropic readily acknowledge this:

While the problems we study can (and often have been) analyzed with other methods, the general "build a microscope" approach lets us learn many things we wouldn't have guessed going in, which will be increasingly important as models grow more sophisticated.

These findings aren’t just scientifically interesting—they represent significant progress towards our goal of understanding AI systems and making sure they’re reliable.

They concede that researchers are still striving toward the goal of reliability and that they are only just now “building a microscope” to improve our understanding. An ethical scientist would not synthesize a new bacteria that he hopes would benefit human health and release it on the public before he even had a microscope to analyze it. Yet here we are.

Moreover, the Anthropic researchers point out that even this advancement (if it is one) in understanding existing AI, that they developed, is hopelessly inadequate:

At the same time, we recognize the limitations of our current approach. Even on short, simple prompts, our method only captures a fraction of the total computation performed by Claude, and the mechanisms we do see may have some artifacts based on our tools which don't reflect what is going on in the underlying model. It currently takes a few hours of human effort to understand the circuits we see, even on prompts with only tens of words. To scale to the thousands of words supporting the complex thinking chains used by modern models, we will need to improve both the method and (perhaps with AI assistance) how we make sense of what we see with it.

No matter how one tries to justify it, this is the epitome of irresponsibility. That Anthropic or any other AI company is working to “look under the hood” of its AI is admirable, but that this is occurring so long after these systems have been incorporated into many critical functions of society is a crime against humanity.

The largest crime ever committed

It seems that Anthropic is no different than Meta, OpenAI, or any other major AI company, either morally or legally. All are in an arms race to acquire the most data possible (whether legally or not) the fastest, and to make billions off the people who actually put the work in to create this body of knowledge. The people who deserve the compensation.

It is not the same as when VCRs or other copying technologies emerged. At least then, the creators got recognition for their creations and the distribution of even pirated copies elevated their popularity. Furthermore, their creations were not “synthesized” or, more aptly put, distorted, into inferior versions of themselves.

Generative AI is an affront to the very thing that humans have long pointed to as what differentiates themselves from other species. It is not innovation, or a “complement” to human creativity, it is the sterilization of human ingenuity into mathematical quantification. It is the democratic imposition of the masses on the standouts whose genius and creativity is what made their work so enduring.

Advocating AI as a “complement” is essentially equating the value of a Facebook meme with that of the Mona Lisa, or suggesting that the former somehow improves the latter. The problem is that the speed with which AI can enable the output of vacuous garbage will eventually overtake and drown that which actually provides value.

Bernie Madoff, infamous for his 65 billion-dollar Ponzi scheme, was infinitesimally small potatoes compared to what criminal enterprises posing as tech companies are doing in the name of artificial intelligence. What is occurring now will not be resolved by scattershot civil suits, half of which will be dismissed by judges who don’t know an algorithm from alchemy.

It will not be resolved by half-assed antitrust suits where the penalty barely reaches a measurable cost of doing business—if such prosecutions are conducted at all, which is rare. (Though it will greatly help if huge companies are broken up like Ma Bell, but for now it is hard to be optimistic).

Source: Judge Beryl A. Howell, Commissioner on the U.S. Sentencing Commission 2004 - 2010. “Sentencing of Antitrust Offenders: What Does The Data Show?” Full text here.

The only solution is to treat this like the massive, global crime that it is. It is the stealing of the foundation of human intellect and distorting it into something trivial, lifeless, and worthless.

AI will not be the savior of humanity because of its emotional indifference and calculational superiority, at least not if it is built to abscond with every remaining shred of value from human intellectual and cultural output. It will be a virus, a plague upon mankind that zombifies the human condition into one in which ruthless efficiency and productivity are the driving force.

But, we’ve already lived that act of the movie. And it sucked. The world isn’t better off because of it. Rather, most are seeing their situations worsen. Depression is on the rise, life expectancy and reproduction are on the decline. The environment is falling apart. Animal species across the world are dying en masse.

Champions of this historic fraud are of two groups—the one that is already benefitting, and the one who thinks it will soon. Both are fools.

If you found this essay informative, consider giving it a like or Buying me A Coffee if you wish to show your support. Thanks.

note that throughout, when using “AI,” this essay is referring to publicly released AI that either is already targeted for large scale profit, or will be, based on its business plan or funding sources.