The Engagement Economy Is A Legal Fraud

Medium, TikTok, YouTube, and many others are just ripping people off

By Loïc Ventre, CC BY-SA 2.0

Suppose you went to college to become a veterinarian for exotic species. You graduate and begin the job hunt. Before you even entered the program, you knew that it would be a challenging field to break into, but your extreme passion led you to take the risk. You achieved excellent grades and buttressed your resume with experience in veterinarian hospitals that treated more commonplace animals. Since then, you have submitted resumes to every zoo and preserve within 100 miles.

Finally! You land a job at your local zoo.

The money isn’t great, but you are told you will get to work with endangered species and that, if you perform well, you will eventually establish yourself as an expert, which will lead to even more opportunity. With a skip in your step, you show up for your first day.

Indeed, it is quite challenging at first. You are mostly just cleaning pens and changing food supplies. Rarely do you ever come any closer to a wild animal than the visitors do. Nevertheless, you persevere, taking every opportunity to illustrate what a terrific, diligent, and skillful worker you are.

Months go by and over that time you find the chance to get a little bit closer to some of the resident creatures. Not that close, but it gives you the sensation that success is just around the corner. Once in a while, the powers-that-be nod in your direction, allowing you to enter a particularly intriguing enclosure with one of the senior caretakers. With it comes a boost in pay. You are delighted. I can really succeed at this, you exclaim to yourself.

Almost a year into your tenure, you have lucked your way into this opportunity a small handful of times. You’re never really sure of the exact reason why, but you suppose it is acknowledgement of your exceptional work ethic and capability at performing. Regardless, you are making some money each month, which helps keep you striving for further selections.

Then one day, you receive an email from the administration. It informs you that you will no longer be paid much for your routine duties, except in the instances when you are given that golden invitation into an enclosure. The message is replete with excuses for why this is so, but none of them have anything to do with you, really. A quick online search reveals that the zoo is having a very good financial year, so that cannot be why your pay is all but gone. It also downplays the change, calling your loss of income a mere “tweak” in their pay structure.

The signor of the email claims that it must account for “shifts based on the interests of visitors,” whatever the hell that means. It also hints that any criticisms of the policy will hurt your chances for future golden invitations, asserting “we often hear from our visitors that these kinds of statements aren’t the ones they want to see.” It follows by proclaiming that the company “loves to support all authentic workers.” Authentic or obedient, you wonder.

The message rings hollow, regardless, because despite having performed admirably over the last several months, the golden invitations have come far less frequently for you and their associated pay has declined each time.

With a frustrated sigh, you close the email. Sure, you could find another place to work, but zoos and exotic animal facilities are few and far between. Moreover, rumor has it that the rest of them are adopting the same paradigm. You could just quit, but then your dream of working with such exquisite creatures might well die with your resignation. But if you don’t resign, you are conceding to what feels an awful lot like corporate exploitation.

The business will still benefit from your work, and its shareholders will still profit handsomely from it. Meanwhile, you will be left toiling for hours per day to earn — at best — pennies, except on those rare occasions when the powers-that-be decide to throw a few extra bones in your direction. You also will not get the exposure you had hoped for — indeed were promised — unless you are profoundly lucky. Worst of all, you can’t even strive to improve your efforts to model them more toward what the administration wants because no one has, or will, tell you what it is they actually want.

Your friends ask you why you don’t just run your own startup operation. You will be your own boss and make your own rules, they enthusiastically gush. But to succeed, you would have to start as a vet for normal animals, household pets or maybe livestock. And there are already an abundance of those, most with existing — and loyal — customer bases. To attract enough business, you would have to spend a lot on marketing, something you know little about and for which you have virtually no capital. Not to mention, the startup costs for basic functions is also prohibitive.

You feel justifiably misled, but worse than that, backed into a corner. Do I want to do this job or not, you ask yourself. Is it worth struggling for free while enriching others on the long odds that somehow I will succeed? Is there any other way to go?

On the last point, you know the answer is yes. Yet, you put a great deal of effort into building your reputation at this zoo. You gave them your all. You were willing to do even more, if only they would have explained what it was that would have satisfied them while simultaneously advancing your career. But, alas, they could not be bothered.

So, you are left with the burning question: should I stay at the zoo?

This is what the engagement economy is like.

Credit: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102–12762 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

People seeking to endeavor in creative careers — writing, music, visual art — have gravitated toward platforms like Medium, Spotify, and YouTube, among many others.

These outfits essentially offer free or very low-cost platforms for creatives to introduce their work to the world. They provide the infrastructure for which many creatives lack the skill, time, or resources to establish themselves. To earn money, creators typically have to meet certain qualifications set by the platforms.

Whatever the basis that allows creators to become revenue generators, profitability on almost all these kinds of platforms is dependent on engagement.

The fallacy of ‘partnership’

Engagement is generally defined as any instance in which an online entity does something in relation to the creative work. (I used ‘entity’ rather than ‘person’ because there is a growing problem of fake engagement, but that’s a discussion for another time).

The ‘something’ typically includes the following:

Liking a piece. On different platforms, it is referred to by various monikers — a ‘clap’ on Medium or ‘thumbs up’ on YouTube — but the notion is largely the same;

Commenting. Everyone is familiar with this, so it needs no further explanation; and, of course,

Consuming. Reading, listening to, or watching the production.

To become eligible to start generating revenue, one must qualify in various ways that vary by platform. On Medium, for example — a platform that I currently use — it costs a writer $50 per year to post paywalled stories that generate income based on engagement numbers. The “qualification” is simply paying for a membership.

On YouTube, a videographer can load work for free, but only begin earning once these metrics are met:

500 subscribers with 3 public uploads in the last 90 days; and

either 3K valid public watch hours in the last 12 months OR 3M public Shorts views in the last 90 days.

For Spotify, two key standards are:

Hit at least 10,000 consumption hours on Spotify in the last 30 days; and

Hit at least 2,000 people who have streamed on Spotify in the last 30 days

Curiously, a common theme among the largest platforms for these qualifying programs is to employ the term ‘Partner.’ Spotify, Medium, and YouTube are prime examples. The idea seems to be that creators become stakeholders in the platform by developing the content that makes it successful and, in exchange, they receive monetary benefits for doing so.

As the allegory that opened this article illustrates, however, this is a decidedly one-sided partnership. Creators are essentially asked to perform the same function repeatedly — create content that people will consume on a large scale. Meanwhile, the platforms are held to no such consistency or, perhaps more importantly, transparency.

Every platform concedes that the value of their existence is wholly based on the content, yet they have no qualms with hiding that value from the creators themselves, and “tweaking” the associated benefits to creators as they see fit, irrespective of the harm both causes. Worse, many of them have toyed with the idea of demonetizing any criticism of such an unfair relationship.

This is not a Partnership. It’s coercion.

In contract law, there is something called an Unconscionable Contract. It is defined as one that is “so severely one-sided and unfair to one of the parties that it is deemed unenforceable under the law.” A court looks for any of the following elements to make the determination that a contract is unconscionable or abusive:

Undue influence;

Duress;

Unequal bargaining power;

Unfair surprise; or

Limiting warranty

Three of these sound strikingly familiar.

Undue Influence

The 2nd Appellate Division of California provided a good explanation for the concept of undue influence as it pertains to business agreements:

By statutory definition undue influence includes “taking an unfair advantage of another’s weakness of mind, or … taking a grossly oppressive and unfair advantage of another’s necessities or distress.” … To make a good contract a man must be a free agent. Pressure of whatever sort which overpowers the will without convincing the judgment is a species of restraint under which no valid contract can be made.

The victim of undue influence need not suffer some serious infirmity like mental decline, poor health, or specific emotional anguish. It only requires “a lessened capacity of the object to make a free contract.” Courts also consider “an application of excessive strength by a dominant subject against a servient object” as an important factor.

People who have spent time on a platform building an audience and producing a library of work are necessarily dependent on the expectations engendered by the platform. They are the servient object.

Making unnegotiated changes after creators have built a brand and come to rely on the revenue and other benefits of the platform unquestionably “lessens” their capacity to do anything about them, let alone overcome the pressure exerted upon them by the new conditions. In effect, they are left with accepting those changes against their will, or leave.

While pro-business types will rest their arguments on “just leave,” this ignores a critical point. Creators who have curated an audience or supplied a large body of work have bestowed upon the platform lasting value, one that is retained by the platform but lost by the creator who departs. Moreover, this is not a legally justifiable position.

David versus Goliath, By Osmar Schindler (1888) Public Domain

Unequal bargaining power and unfair surprise

The balance of power between the parties to a contract plays a role in determining the fairness of the overall agreement or its provisions. This is probably because:

courts view businessmen as possessed of a greater degree of commercial understanding and substantially more economic muscle than the ordinary consumer.

Creators on platforms like YouTube are, without doubt, far more akin to “ordinary consumers” than evenly-situated businesspeople. This normally shifts the responsibility to maintain fairness on the stronger party. As the Ohio Supreme Court has noted,

where the written contract is standardized and between parties of unequal bargaining power, an ambiguity in the writing will be interpreted strictly against the drafter and in favor of the nondrafting party.

The nondrafting party in every instance of the engagement economy is the creator.

An essential element to a finding that there is unequal bargaining power among the parties is when there is “no real negotiation and an absence of meaningful choice.” This can lead to a “contract of adhesion,” which affords the “subscribing party only the opportunity to adhere to the contract or reject it.”

Some contracts that seem similar to adhesion contracts are allowable under law, such as employment contracts, but nonetheless have restrictions. Agreements between creators and platforms bear some semblance to employment contracts.

Many employment contracts contain nonnegotiable provisions. While a nonnegotiable employment contract is not per se unconscionable, even though there is an acute imbalance of power between the parties, surprise elements can render it so.

Surprise involves the extent to which the terms of the bargain are hidden in a “prolix printed form” drafted by a party in a superior bargaining position.

A “prolix” form is one that is tediously prolonged or wordy.

The ability to arbitrarily change the payout structure, or “tweak” it — in the words of Medium’s administration — constitutes a surprise, as a matter of law. This includes applying different weights to the engagement metrics as well as imposing new (i.e. surprising) content-based restrictions or bans that lack any legal justification. And all of this is typically hidden in prolix Terms of Service (if revealed at all).

The business relationship between large platforms and creators is undeniably one of unequal bargaining power littered with unfair surprise.

So how is it legal?

Aaron Swartz killed himself because he faced 35 years in prison for computer-related crimes. His case shined a brief light on the pernicious nature of Terms of Service, but that light faded quickly. Source: The Atlantic

Terms of Service as the excuse

High-paid corporate attorneys for these platforms will claim that all of this is irrelevant because they do not offer contracts at all. Rather, they provide a service with which creators engage in the hopes that they will earn some revenue, governed under their Terms of Service (ToS).

What they may be more bashful about admitting is that in providing that service, they effectively strip creators of most of their legal rights while retaining their own. Consider this portion of YouTube’s ToS, that are quite similar to all major tech platforms out there, including social media:

By providing Content to the Service, you grant to YouTube a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free, sublicensable and transferable license to use that Content (including to reproduce, distribute, prepare derivative works, display and perform it) in connection with the Service and YouTube’s (and its successors’ and Affiliates’) business, including for the purpose of promoting and redistributing part or all of the Service.

Here are Medium’s:

Unless otherwise agreed in writing, by submitting, posting, or displaying content on or through the Services, you grant Medium a nonexclusive, royalty-free, worldwide, fully paid, and sublicensable license to use, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, translate, create derivative works from, distribute, publicly perform and display your content and any name, username or likeness provided in connection with your content in all media formats and distribution methods now known or later developed on the Services.

Cleverly concealed within all that legal jargon is an entirely unequal agreement. It is claiming substantial rights to a license to creator content, with little guaranteed in return (note the ‘royalty-free’ phraseology, for example).

Despite not offering any concrete reciprocation, they admit that they can use that content to bolster their own business “for the purpose of promoting and redistributing part or all of the Service.” In Medium’s case, the ToS even enshrines its right to your content through “methods now known or later developed.”

After reading the ToS of several platforms, one might reasonably conclude that their lawyers simply traded the same boilerplate template (worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free, sublicensable and transferable) to create them.

ToS become suspiciously close to a contract of adhesion with statements like these:

We’ll let you know in writing when we make changes that might impact you. If you do not agree to the modified terms, you may stop using the relevant feature, or terminate your agreement with us.

Or:

You’re free to stop using our Services at any time. We reserve the right to suspend or terminate your access to the Services with or without notice.

There is no better way to interpret this than how the 9th Circuit defined one type of unequal agreement. That is, one that affords the “subscribing party only the opportunity to adhere to the contract or reject it.” Basically, accept our terms or get out.

A while back, I quoted a blogger who perfectly articulated the general character of ToS:

[ToS] are long, boring and often baffling. Reading them is a tedious, joyless pursuit, and for the majority of us who aren’t legally trained, trying to understand them amounts to little more than our best guess. What’s more, there’s just so many of them. And they’re frequently changing, which means keeping up to date is far from easy. Faced with all this potential hassle, it’s no surprise we opt for convenience by choosing instead to simply click our acceptance. After all, we’re busy people with things to do, and ultimately, we just want stuff now — the site, the app or the online service.

To that, I added “Companies write them this way purposely to hide critical provisions to which consumers unwittingly agree.” This is especially true when the ToS apply to creators.

The entire ToS universe is a fraud perpetuated on the people who generate value, so that those who buttress it with relatively little investment or effort can benefit. If there is doubt, consider what amount of actual work and capital it takes to maintain a writer’s platform.

It needs a space on the internet, data storage, a payment system, and some level of anti-fraud processes. Additional features, such as nonsense algorithms to “boost” certain material, often harm the creators more than they produce general value.

For several years, I developed, hosted, and maintained a website and mobile application that was far more complex than any of these, including YouTube. All of that cost about $12,000 per year.

Yes, big platforms require more storage and employees, but that is both a consequence and benefit of added content (i.e value). The idea that most of these billion-dollar platforms can only afford to pay creators peanuts is an insult, to be as charitable as possible.

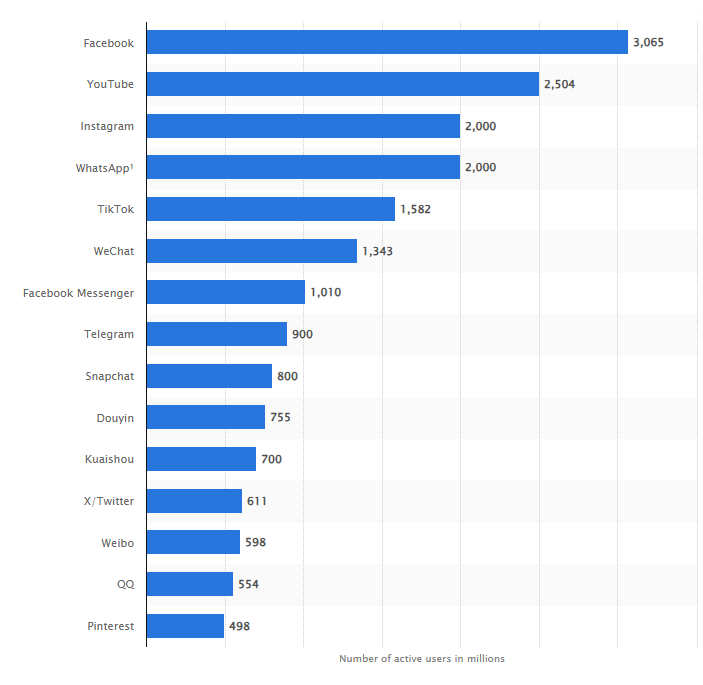

Source: Statista

The engagement economy can be made fair for creators

YouTube generated $36.1 billion revenue in 2024, a 14.6% increase year-on-year, according to businessofapps.com. The number of creators on YouTube was estimated to be around 64 million that year. If every single creator received an equal annual check, it would have amounted to around $500.

Partner programs are not per se unfair. But they are in the way that platforms currently run them.

Returning to the YouTube example, limiting payments to only those in its Partner Program would have raised the income per qualified creator. It would be fair as a business practice to further dissect that amount by engagement (i.e. more popular works get paid more). But only if the terms were and remain clear and consistent.

In other words, YouTube, Spotify and the others could operate under their current paradigm in a moral way simply by making it clear to the creators what the pay rate and other standards actually are, and keeping them consistent. This would enable creators to develop their content with the various metrics in mind (if that’s their goal), and to receive the expected benefit of doing so.

Notably, I think this is a dangerous way to distribute content for a variety of other reasons, but here we are talking about contractual legality, not social responsibility.

I discussed in detail fixing the ToS debacle in another article here on Substack, so I will only provide the summary here:

Companies should not be allowed to change the ToS without the explicit consent of users (except in [very] specific circumstances that might include security or core functionality). In other words, a user should not have to adhere to new ToS to keep using an application they already have used or risk losing their data or access merely because a company wants to procure and sell more user data. ToS should not function as a coerced “agreement” forcing customers into one-sided giveaways to utilize popular or necessary services.

In that case, I was talking more about consumers of various services, such as social media, but the principle applies here. Unless governments and courts begin to treat ToS more like contracts, they will remain coercive tools to steal from the public and creators.

Source: peakprosperity.com

Take the union approach

No politician is going to fix this without extreme pressure put upon them. For half a century, the United States government has shifted to a business-first political paradigm that has served an incredibly small population of thieves while slowly destroying the lives of everyone else. If history is any proof, it will take a widespread, unified movement to end the abuse.

Sadly, partisanship and self-destructive ideology is severely impeding such unity, bolstered in large part by these same thieves who own nearly all the major distributors of information. It is reflected in social media, comments sections, and voting booths.

Blind allegiance to frauds has convinced many to bite off their noses to spite their own faces. Indeed, this is evident in the composition of the recently elected administration, which consists of an unprecedented number of billionaires. A development that surprises no one who has paid attention.

Until people see the harm they are doing to themselves by allowing this to continue, things will only continue to get much, much worse. Good creators will disappear, replaced by content-mill garbage. Meanwhile, venture capitalists and investors will keep widening the wealth gap as society becomes ever more bland and intellectually blunt.

** Articles post on Saturdays. **

If you found this essay informative, consider giving it a like or Buying me A Coffee if you wish to show your support. Thanks.