He thought of the telescreen with its never-sleeping ear. They could spy upon you night and day, but if you kept your head, you could still outwit them. With all their cleverness, they had never mastered the secret of finding out what another human being was thinking.

—George Orwell, 1984

Many televisions now employ a surveillance technology called Automatic Content Recognition (ACR). It allows them to spy on everything you watch. Quietly mounted software takes a snapshot of your screen twice per second. It runs the images against a database of content and ads, then pairs it with the “profile” data of the user. Purportedly, the personally identifiable information of the user is removed. Whatever is ultimately amalgamated is then used to pummel the user—you—with targeted ads.

Smart TV manufacturers earned $18.6 billion in smart TV ad revenue in 2022. In a VIZIO earnings call, Adam Townsend noted that its SmartCast platform grew by 1.3 million users from 2022 to 2023, with a 58% increase in watch time. Coupled with an 8% decline in unit shipments and price over the last year, this indicates that the desire of manufacturers to generate ad revenue will only increase. In a world already littered with surveillance mechanisms, including within your own household, it seems Orwell’s 1984 is well upon us.

Eyes everywhere

Most people have known—or at least believed—for some time that their devices spy on them. People often remark about how an ad appears in their Facebook or other feed, seemingly targeted to them based on a conversation had just previously. Thousands upon thousands of articles have been written on some facet or another about the abuse of this information dragnet, yet governments across much of the world continue to ignore it.

Recently, I gave an interview to Online Khabar, the most viewed news portal in Nepal. In it, I commented on the issue of data privacy, snooping, and hacking. In addition to encouraging “a culture of responsible digital behaviour,” I emphasized the need for governments “to focus on robust regulation coupled with substantial penalties proportional to the scale and impact of violations.”

Source: Online Khabar

The closest any government has come to implementing a strong legal framework for data privacy protection is the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This regulation provides a good guideline for other governments, but without more following suit it will not be enough.

Many governments have instead opted to targeting specific applications. In Nepal, for example, the government recently banned TikTok just as the US state of Montana has. I made a long argument about why this approach is both foolhardy and pointless. On the former, banning a specific app opens the door to increased vulnerability. Regarding Montana, I wrote:

Users who have already downloaded the app or who do so after the ban while out of state will run into another vulnerability caused by the law. Because the law does not require users to delete the app if they already have it, they will almost certainly continue to use it.

Unfortunately, without access to it via the Google or Apple stores, they will not receive updates and security patches that would normally occur automatically. If an attacker finds an exploit in any versions of the TikTok app, they can simply target Montana users who will not have the available fix for the vulnerability to steal data or money (including Chinese spies, if they choose to).

Attackers can specifically target Montana users simply by trolling their social media to find people who locate themselves there. Rest assured that the dark web will contain lists of Montana users of outdated TikTok apps before long. Undoubtedly, this will be a sufficient pool to satisfy their malevolent intent.

But this applies to anywhere a ban is implemented.

Banning one app is pointless, anyway. Absent a wholesale ban on all social media, including websites with comment sections, chat applications, and anywhere else people can collectively meet and speak, misinformation and spying will nonetheless proliferate.

Technological Ignorance - Weaponizing Xenophobia

Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share! The Evidence Files is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Montana became the first US state to

Banning applications represents a lazy way to show a government is doing something about privacy without actually doing anything substantive. Ever-present data vacuuming remains a true threat to security, and a true threat to privacy. Failing to take broad regulatory action allows the continuance of wide-scale theft. Vindictive governments abuse free-flowing data to commit crimes against their own citizens. Free-flowing data also poses threats to national security when inept politicians expose themselves to potential blackmail.

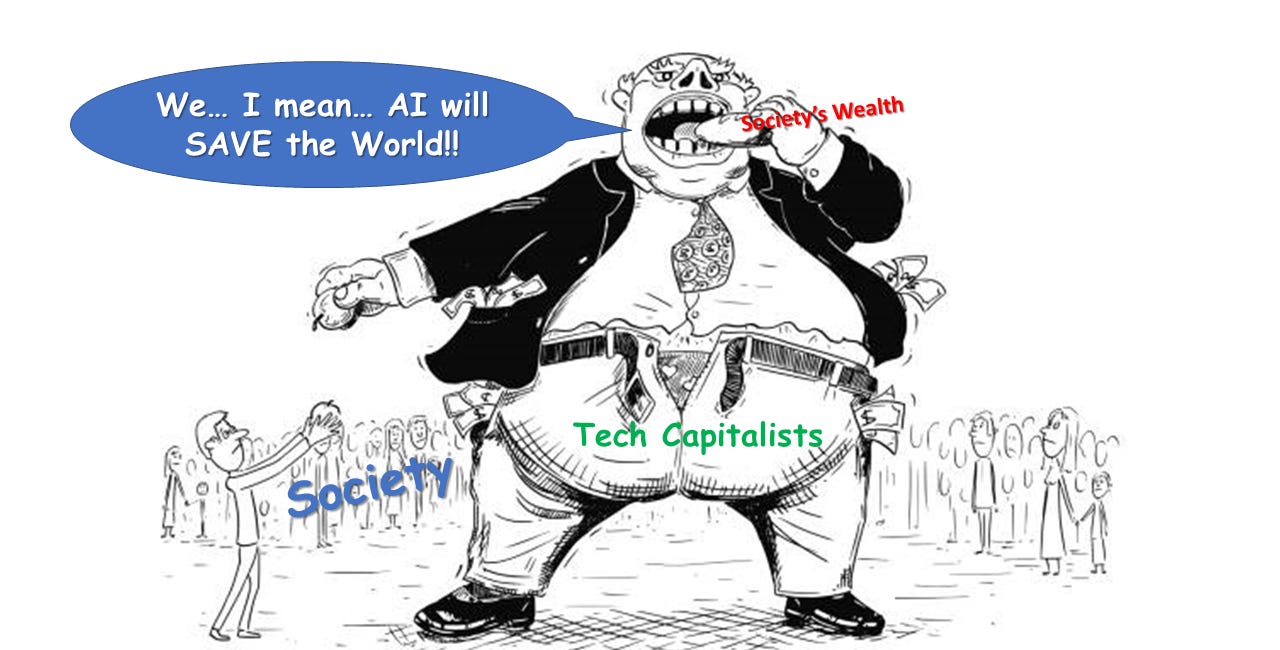

The release of woefully underdeveloped programs characterized as “Artificial Intelligence” enriches bloviating idiots at the expense of a society that increasingly cannot discern what is real or not. These programs steal data from across the internet to function. Some companies readily admit their product’s own potential for causing harm, but release them anyway in the name of profit.

All of this finds its roots in governmental apathy. Failing to engage in real, toothy regulation means that a very small segment of the population can perpetuate its widescale fraud against society, irrespective of the consequences.

Selling out

One needs only to look at the erosion in Silicon Valley to see the inevitable outcome of allowing this free-for-all to continue.

Huge scandals such as the Theranos fraud, the imminent collapse of Facebook (ineffectively renamed Meta), the rapid destruction of Twitter, and the recent failure of Silicon Valley Bank (including what looks an awful lot like pre-collapse insider trading by its executives) have smeared the entire community with the stain of greed and filth.

And those only overshadow the myriad other scandals, such as the nearly $400 million Google paid for allegedly tracking private internet use, the donor-advised funds (DAFs) issue, or simply the typically lousy work conditions, among others.

The apparently precipitous fall of nearly all the big names of Silicon Valley seems like it should have resulted in a virtual explosion of startups. Alas, like the Carnegie days of steel, big business does not concede power easily, and it rarely eschews monopolizing the market. Raghuram G. Rajan, Luigi Zingales, and Sai Krishna Kamepalli explained how when big companies acquire startups, they tend to create “kill zones.”

These researchers noted that because big tech companies trade in user data, there is little incentive for new application developers to attempt to build their product. Selling out to the big companies is far more lucrative, and easier. The big tech companies maintain their hold on the industry, and innovation is limited to the agendas or business models of them only. As a result, the previous two decades have seen a significant decline in overall innovation.

In addition to their actions, their words also give them away.

Sam Altman, former CEO of OpenAI, whined to the press about his “many concerns” about the EU’s effort to regulate AI there. His complaint centered on the possible designation of ChatGPT as “high risk” under the impending law. Notably, Altman confessed that he did not know if OpenAI could meet the “safety and transparency requirements,” which might force them to remove access to ChatGPT in any EU jurisdiction.

Think about the implications there, for a moment. Altman openly admitted that he did not know if the company could meet safety or transparency standards. Replace ChatGPT with “automobile” and ask yourself if anyone would agree to still allow the company to release the product.

Ignoring the safety issue for a moment, one also must wonder why Altman did not believe OpenAI could (not would) meet transparency requirements, if in fact that is what he meant. The reason is clear: no regulation means a massive boon to venture capitalists and companies that profit from invading the public’s privacy. It is why they go to such lengths to stop regulation.

Altman essentially threatened the EU with the removal of a product that at the time was a very sought-after item (despite the fact that it was, and in many ways continues to be, garbage). He did not care about the quality of the product or safety of its users, just about its ability to make money.

Cory Doctorow, a journalist out of Canada, created a rather apt term for this: “enshittification.” Enshittification is when “platforms go from being initially good to their users, to abusing them to make things better for their business customers and finally to abusing those customers in order to claw back all the value for themselves.”

Modern snake oil salesmen

To maintain the flow of capital despite the decline of their products’ true worth, modern-day Frank Abagnales like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Marc Andreessen, and others leverage their wealth and ludicrous narratives of genius and vision.

They tell tall tales of how their newest fancy gadget will “save humanity” and other twaddle. Because this group of clowns cannot produce viable platforms that make money from a legitimate, useful function they instead need to profit from the very identity of the users themselves. And sadly, it seems all other tech is headed in that direction.

Returning to televisions, the market for “dumb” TVs—a serious misnomer given the vulnerabilities, spying software, and other refuse that comes with so-called “smart” ones—has shrunk precipitously in the last few years. In some cases, one needs to have a business account with a retailer to even purchase a non-internet connected (dumb) TV.

Even where retailers still offer them, consumers find limited choices. Many major brand names no longer produce them, leaving consumers stuck with scouring the internet for hours on end to find more obscure brands. As the earnings call for VIZIO—cited above—made clear, companies do not profit much from manufacturing anymore, so they rely on selling their users’ data to the highest bidder. In a few years, successfully locating a dumb TV for purchase may require the same effort as finding a dot matrix printer or phonograph.

Making people the commodity

The result of this economic shift to making people the commodity has severe implications. First, people will soon find it impossible to function in society at all without living under daily surveillance—if we are not there already. Living without a car in many locales or for certain demographic sections of society is near impossible, yet modern cars spy on their drivers. Foregoing owning an automobile, though, remains easier than living without a cell phone.

So many daily functions either require having one, or have become so tedious to do without one that people simply do not have the time or patience to go without them. Moreover, many jobs require an immediate, ongoing connection leaving those employees without the choice of living without one. As the Supreme Court noted in 2014:

The term "cell phone" is itself misleading shorthand; many of these devices are in fact minicomputers that also happen to have the capacity to be used as a telephone. They could just as easily be called cameras, video players, rolodexes, calendars, tape recorders, libraries, diaries, albums, televisions, maps, or newspapers.

The court a decade ago recognized the disproportionate amount of data collected on that single device. What it could not consider then, however, is that the enormity of the volume of data scooped up by cell phones would soon be rivaled by almost everything else.

The IoT—Internet of Trash

IoT (“Internet of Things”) devices have become ubiquitous and collect obscene amounts of data from even our most private spaces. Toys, refrigerators, thermostats, security cameras, fitness trackers, lights—all of these come with internet connections nowadays.

Retail outlets employ spy cameras, Bluetooth beacons, in-store WiFi tracking, and other methodologies to track you. Traffic cameras watch your every move. Static and dynamically mounted license plate readers log every time your car passes by. Every one of these devices uploads this information into massive databases.

Notwithstanding this sort of physical invasion of privacy, what happens on the internet is far worse. Cookies and supercookies, adware, and malware all secretly collect data, but others do it more openly. Amazon, Google, and Meta, for example, provide a way for users to see the data they collect (though not easily for most people), but they unabashedly continue scooping insane volumes.

Many companies, including Google, can and do read or at least scan your email. They do this purportedly to check for spam or malware, but they do it nonetheless. Every major platform collects “public” information as a matter of routine. This includes keywords, URLs, device specifications, browser history, and virtually anything else a person might do or reveal while online.

Why We Need Strong Data Privacy Laws

Information is power. Throughout the annals of history, acquiring and strategically using sensitive or private information has led to everything from the revelations of the immoral to the toppling of entire empires. For the common folk of today, the dissemination of private data leads to cyberstalking, cyberbullying, theft, scams, and various other crimes or personal embarrassments.

What is worse is that the people who benefit most from these uninhibited data collection regimes tend to be the worst human beings on the planet. They corrupt governments, impoverish people, pollute the environment, and just generally violate the law with impunity.

Even when an occasional legal authority steps in, the punishments are laughable. The highest penalty under the GDPR, probably among the most stringent data privacy laws on the books anywhere, is only 5% of a defendant company’s annual revenue. When it slapped Meta with a “record” $1.3 billion fine in 2023, the company still pulled in $113 billion in revenue. Under that law, a fine can only be imposed at all if the violation was “intentional and negligent.”

The lack of sufficient regulation allows companies to operate in regular violation of law as a “cost of doing business.” Or, to avoid violations at all, they engage in chicanery to confuse or inconvenience users to force them into “voluntary” disgorgement of their personal information. By this I refer to the routinely challenging ways companies enable consumers to “opt out” of certain policies. Even if a user manages to navigate the process correctly, they have no real means to discern whether the privacy violations have stopped.

Experts note that what constitutes a violation is frequently unclear, helped in no small part by the mishmash of laws that poorly define terms like data, collection, purpose, and other important concepts. Critics note that the GDPR also largely fails in this regard. Shortly after its enactment, Mindaugas Kiskis wrote:

“Legitimate business interest” is one of the grounds for legal processing of personal data provided by the GDPR, what it means is not clear, even though official explanations on the legitimate interests to process personal data under the previous rules (admittedly much simpler) span almost 70 small print pages.

Other data dealers are happy to remain in the shadows and manage risks by doing their business through corporate shells or from outside of the EU. The EU itself seems to have second thoughts about the extraterritoriality of the GDPR. The concessions in the leaked travaux préparatoires of the EU free trade agreement negotiations with third countries imply the willingness to limit the reach of the GDPR.

In other words, the so-far most robust data protection regime in the world contains enough loopholes to render it almost useless.

Understanding the effects of no data privacy are obvious; how to legislate it is not. Failing to restrict private data contributes to severe intrusions of individual privacy. From a psychological perspective, personal privacy allows introspection, avoids embarrassment, and is critical to mental health. One need only look to celebrities who very publicly fall into disrepute often from the challenges associated with their fame as illustrations.

Personal privacy is fundamental to freedom. The revelation of certain details might cause reputational damage, especially in the absence of any contextual aspects that might clarify a fact pattern. Cyberbullies use this kind of information to target their victims, and the age of victims continues to drop. In 2019, one survey found that 47.7% of children six to ten years old had suffered online bullying. Six to Ten Years Old. Even pre-teen kids are not safe in an environment where data privacy remains unregulated.

In addition to the personal detriments faced by individuals whose data passes freely across businesses and others, the dangers to society at large also raise blaring alarms. The Renaissance Fair-turned-Coup-Attempt in the United States in 2021 was driven in large part by conspiracy theories and misinformation carefully patched together with the help of the personal data of hundreds of millions of people originally stolen to help elect Donald Trump in 2016.

Facebook settled with the US government for allowing Cambridge Analytica to scrape that data. Trump and his cronies weaponized many of the nonsensical stories that emerged from that campaign in addition to their own Big Lie campaign to convince thousands of people to descend upon the Capitol and engage in violence in 2021.

Aside from the attempt to overthrow the US government, Cambridge Analytica’s crimes alone led to similar crises In Ukraine, Malaysia, Kenya, and Brazil, among others. They are not the only ones doing it. No data privacy regulation directly contributes to bloody coups and even wars. This is not a sustainable system.

What to Do?

While it is impossible here for me to provide a full legislative proposal for addressing this complex, global problem, there are some simple ideas from which any framework of law should work.

Terms of Service

To start, do away with the current way companies create, distribute, and use Terms of Service (ToS). Most companies compose their ToS in language consumers find difficult to understand. As one blogger wrote:

[ToS] are long, boring and often baffling. Reading them is a tedious, joyless pursuit, and for the majority of us who aren’t legally trained, trying to understand them amounts to little more than our best guess. What’s more, there’s just so many of them. And they’re frequently changing, which means keeping up to date is far from easy. Faced with all this potential hassle, it’s no surprise we opt for convenience by choosing instead to simply click our acceptance. After all, we’re busy people with things to do, and ultimately, we just want stuff now – the site, the app or the online service.

Companies write them this way purposely to hide critical provisions to which consumers unwittingly agree. For example, some companies retain ownership of a purchase—even a physical object—under their ToS, effectively selling you only a license to the item, not the thing itself.

In other cases, ToS provide companies rights to use your own content. Facebook, for instance, obtains “a nonexclusive, transferable, sublicensable, royalty-free, and worldwide license to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, translate, and create derivative works of your content.”

Put in plain English, Facebook can do whatever it wants with the photos you post on its platform, including profit from them. Intel prevents its consumers from publishing benchmark or comparative tests of its software. In other words, users cannot publicly post reviews of Intel’s software.

After writing their ToS in dense, often incomprehensible language they then make it challenging for consumers to read at all. This often happens when purchasing a phone. Companies provide their ToS on a company tablet where the customer must click a link to read it or can go to the company’s website instead. Of course, few will do this while in a store before signing the dotted line.

In many cases, reading the whole document in the store would be wildly impractical. Some ToS exceed 50 pages. Still others attempt to bind users to their ToS by employing a method called “Browserwrap.” This occurs when a pop-up emerges as a user attempts to enter a website or platform, the pop-up notifies the user that proceeding to the site means that the user agrees to the ToS (which is often represented as a link in the pop-up the user must click). The user effectively “agrees” to the ToS simply by proceeding, without having read a single word of them.

Regulators must prohibit these types of activities or at least render them unenforceable in court. For ToS to be binding, they should be required to use simplified language and be made available with ease—including to the general public—for scrutiny. To be enforceable, consumers must actively agree by checking boxes along the way indicating they read various sections, or through another method like this.

Companies should not be allowed to change the ToS without the explicit consent of users (except in specific circumstances that might include security or core functionality). In other words, a user should not have to adhere to new ToS to keep using an application they already have used or risk losing their data or access merely because a company wants to procure and sell more user data. ToS should not function as a coerced “agreement” forcing customers into one-sided giveaways to utilize popular or necessary services.

Data Collection

All company data collection of an application, program, or device should only commence upon an “opt-in” from the consumer. Data collected out of necessity should also require an opt-in from the consumer. This means consumers would actively select the option to allow the selling or sharing of their data. Eliminate automatic opt-ins.

Governments should dispense with any characterization of data for sale or sharing to prevent loopholes like those in the GDPR. Establishing robust regulations on data collection practices improves companies’ security practices, according to Wojciech Wiewiórowski, the European Data Protection Supervisor. Moreover, companies have reduced the production of applications designed primarily to profit from user data under such legal regimes.

One study examined apps in the Google Play Store from 2016 through 2019, before and after the implementation of the GDPR. The researchers found a one-third reduction in new apps following the advent of the law. At the same time, usage of apps increased by around 25%. This means that people are using more quality apps more often, and people are producing fewer of the lousy ones. This enhances overall security.

Consent for data collection, sharing, and selling needs to extend to all uses, especially in training Artificial Intelligence. The OECD.AI Policy Observatory has outlined aspects of data privacy law that legislation directed to AI must include. Examples are employing data cards (which evaluate training sets to determine their appropriateness for their expected use), protections against producing likenesses, and standards for transparency. In addition, AI regulation should, like other frameworks, require that companies scraping data for training must first receive consent, including for publicly available information.

Punishment

As the lagging compliance by the richest companies under the GDPR shows, punishment for violations of data protection laws demands proportional and painful punishments.

In 2021, Amazon received its own “record-breaking” fine of about $887 million for violations of data privacy. Amazon’s revenue in just the 4th quarter of that year reached $137.4 billion—more than 100x the amount of the fine. The company said of the outcome, “The decision relating to how we show customers relevant advertising relies on subjective and untested interpretations of European privacy law, and the proposed fine is entirely out of proportion with even that interpretation.” It also filed an appeal.

Data regulators in Europe have a history of reducing fines by nearly a factor of 10 on appeals, such as in the case of British Airways and the Marriott Hotels. In the worst case for Amazon, the appeal will uphold the fine. In either scenario, the punishment hardly fits the conduct and does absolutely nothing to deter future abuses.

Compare that fine to that of the EU’s Antitrust Commission. In an antitrust case against Amazon the same year, that regulatory body reached a settlement requiring the company to change its business practices—a rather weak-kneed result. But, had the Commission elected to impose a fine, it had the legal authority to levy an amount of 10% of Amazon’s global annual revenue—about $47 billion in that case.

Vox described the result of the agreement this way:

The deal marks the first time in Amazon’s history it has made a bevy of changes as the result of a government investigation, and it could serve as a blueprint for deals that regulators in the US could push for over concerns of anti-competitive behavior.

While this probably still comprised a win for Amazon, especially given that some experts believe Amazon intended to make the changes anyway, it does indicate that truly hefty fines can compel even the biggest tech companies to comply with regulators. For a data privacy legal regime to succeed, it must contain similar punitive provisions—ones fierce enough to frighten companies earning hundreds of billions of dollars every quarter into compliance.

Conclusion

Commentators on the subject often state that “the costs associated with more stringent data privacy regulation are felt most acutely by smaller companies.” What they are suggesting is that creating legal frameworks is essentially unfair because it stifles startups and small businesses who cannot bear the costs of compliance. They point to a reduction in investments in small to medium companies that occurred in concert with the implementation of the GDPR. From this, they conclude such things like:

Advocates for stringent privacy regulations point to the value of a right to privacy, but this right does not exist in a vacuum. Analysis of the impact of Europe’s GDPR suggests that there is a cost to over-valuing privacy through stringent regulation, both in the economic damage and the tradeoffs to other rights. As policymakers consider potential data privacy regulation in the United States, they should avoid an approach that prioritizes privacy above all else and seek to build on the benefits of the current U.S. approach that focuses on identifiable and quantifiable harms.

The notion of “over-valuing” privacy stinks of the same rot that much louder venture capitalists regularly spew. While others have argued that regulation like the GDPR interferes with user rights, the evidence suggests that even that supposedly stringent law still favors business economic interests over individual privacy rights. In other words, we have no example to show how a proper data protection regime would work because one does not yet exist.

Despite its series of flaws, including its defanged punitive provisions, the GDPR illustrates that an even stronger set of laws, ones that appropriately punish violators, is exactly what is needed. Concerns about stifling competition and innovation can easily be dismissed by incorporating a proper level of proportionality. This will likewise eviscerate the current practice of the biggest companies accepting enormous fines as mere costs of doing business.

As the onslaught of breaches over the last few years continues to victimize people by the millions, the time is long past for governments to act. It would be exciting to see smaller governments lead the charge on this as the bigger ones have shown an uncomfortably cozy relationship with big tech companies. In places like the United States where the government seemingly continues to court relationships with some of the most corrupt companies and executives on the planet, action may need to start with the states as California has done with its CCPA.

To read my analysis of Marc Andreessen’s argument against regulating AI, click below. Thanks for reading!

Venture Capitalist Makes a Strong Argument for Regulating AI (without meaning to)

Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share! Marc Andreessen has published a long-winded, self-indulgent piece on the future of AI, that includes a broad range of “analysis” on what he thinks people are right—and, mostly, wrong—about regarding their fears about the future of an AI-driven world. Andreessen is a ve…

* * *

I am the executive director of the EALS Global Foundation. You can find me at the Evidence Files Medium page for essays on law, politics, and history; follow the Evidence Files Facebook for regular updates, or Buy me A Coffee if you wish to support my work.

We are all a product of our environment and now this is forcing us into being controlled by things we aren't capable of fighting. We have been lynched by these companies and our governments that get monies secretly funneled to them.