Photo by Tobias Bjerknes on Unsplash

Some scientists think that the entire cosmos might be two-dimensional data projected as a 3-D image that is perceived as reality. They call this idea the holographic universe, and there is substantial evidence for it. If someday an entity exists that can read that data like people read books, what will humanity’s chapter look like?

This essay explores the path humans took to arrive at the present moment, and speculates on the conclusion it portends. It is meant as a thought exercise — a way to think about who we are, what we’ve believed, and why. And, most importantly, what it all means for who we will become.

If most of human misery and inequality and conflict and violence is a matter of the stories that people are telling themselves, then you see that virtually all of human suffering and chaos is just tissue thin… it's a bad dream. It's just thoughts that people are finding compelling and they could cease to find those thoughts compelling. —Sam Harris (2025)

Introduction

Thousands of human generations lived and died before a plucky naturalist with a ‘burning zeal’ for learning recognized the impact of the environment on the evolution of creatures, that certain barriers could create substantial variations between members of the same species. Charles Darwin observed this among many creatures, but finches were perhaps his most famous example.

Humans were not fully excepted from this process. Time and space caused them to develop certain traits that seemed to distinguish them. Their skin colors spread across a spectrum of light to dark; bodily features, language, and cultural proclivities took on various manifestations.

But these differences were mostly superficial. Humans had lived for only a blip of epochal time before they embarked on a radically new route, one that carved a future from them that was unique among earthly species. As a result, they never diverged from each other all that much.

Ancestors of modern humans dispersed from one region and interbred with other hominids, ultimately culminating in a new species later pretentiously named homo sapiens. Small groups became larger social units that crashed together to form a super society—an enormously complex, but singular community.

The development of this super society occurred slowly, in fits and starts, leaving ample time for the fear of others to infect then fester, but its momentum was persistent and irreversible.

This is not to say humans stopped evolving. Many evolutionary biologists argued that humans were evolving faster than ever, though perhaps affected more heavily by cultural rather than environmental factors. Dissimilarities caused by physical origin and separation were relegated to a matter of minimal degree, while cultural influences that advanced conformity spread at the literal speed of light, carried by a vast global network.

By the 21st century, most people ate the same or similar food, were treated with the same medicines or received the same medical procedures. They adapted to their environment through artificial manipulation, such as controlled heat or air conditioning. Media and entertainers spread social and political trends to worldwide audiences.

Communal choices and their subsequent effects were felt nearly everywhere, for better and worse. Indeed, certain scourges arising from shared habits became global problems, such as lifestyle-induced heart disease or diabetes.

Group habits also had a profound impact on the environment, which steered the species toward an evolutionary cliff. Some experts warned that there were high odds that the progression of human development had rendered the species incapable of adequately stemming its destruction of the environment—and, thereby, itself. They wrote:

When the patterns and processes of long-term human evolution in the environment are also considered, there is no clear and safe path through the Anthropocene.

With the knowledge that humanity evolved into a single civilization, dependent upon yet able to manipulate its external environment, an objective observer would assume that establishing wise governance would have been among the highest of priorities. Millennia of experience should have ensured that people could identify the traits requisite to capable leaders, those who would do their best to avoid ruinous policies, and would choose them over self-interested charlatans. Alas, that is not what happened.

The human propensity for stubborn persistence knew no bounds, despite famous apocryphal warnings. People preferred to make excuses for past failures, excuses that allowed them to continuously reduce their standards to accept present-day shortcomings. It was an apologetic deference to the easy path. It derived from a desperation to be ruled, to be absolved of all responsibility for ongoing travesties, to blame bogeymen for systemic and personal failures.

The delusions of their poorly chosen leaders permeated the realities that humans generated for themselves. From early on this set the species on a path of doom, with many others suffering as collateral damage. Numerous opportunities arose to change course, but humans repeatedly ignored them.

Civilization is the limitless multiplication of unnecessary necessities.

—Mark Twain (ca. 1870)

The Homo convergence

As humans capitalized on the benefits of social connections, some learned that they could strengthen their position in nature by creating shared spaces—civilizations. Organizing structured societies enabled people to bolster their ability to satisfy many of their needs. Collectivity increased security, which made successful procreation more achievable. Agriculture provided consistent sustenance. Construction allowed for storage of critical supplies and protection from the elements. And, later, specialization increased the efficacy of all of these.

Early civilizations remained largely isolated from one another, a product of the vastness of the planet and a comparably small number of people. Population sizes depended upon collective success, and those successes were heavily dependent upon and influenced by environmental conditions.

As humans became more adept at overcoming natural impediments, they grew their power within the hierarchy of living creatures, in no small part due to their ability to increase their population. Those that achieved this sooner began to dominate other creatures, including other human social units. This occurred over thousands of years.

Scholars regularly debated the fundamental factor behind humanity’s ascendence. One treatise that gained unusual popular appeal—Guns, Germs, and Steel, by Jared Diamond—was criticized for emphasizing what amounted to luck and dismissing the active choice of individuals. As one critic put it:

For Diamond, guns and steel were just technologies that happened to fall into the hands of one’s collective ancestors. And, just to make things fair, they only marginally benefited Westerners over their Indigenous foes in the New World because the real conquest was accomplished by other forces floating free in the cosmic lottery–submicroscopic pathogens. [quoting Wilcox 2010 : 123]

It seemed that, to some, it was sacrilege to proclaim that humans were barely responsible for their self-perceived successes, that external factors no one controlled made all the difference. But this reaction was wrong-headed, a reflection of the arrogance that long-infected the species.

For, despite their conceit, agency was important but peripheral. Luck was crucial. While it was certainly true that societies could dominate their neighbors, success required many elements to come into alignment just so. Likewise, individuals could assume power over their societies, but the realization and desire to actualize it was not enough without the benefit of chance.

This was proved by the great number of wannabes who tried and failed to become dictators irrespective of their skill and tenacity, and by those who obtained power while never actively pursuing it or whose station in life all but guaranteed they would acquire it.

In any case, when these forces combined—agency and luck—power became possible.

What made power so dangerous was that after acquiring it, maintaining it was often the easier part — for the self-anointed elite class, if not for the individuals. Early seekers of power discovered that fabricating narratives of divine selection or mandates provided the foundation for generational control. Generational control made the hoarding of resources possible. Amassed resources allowed for the manipulation of the structure of society itself, an exploit that removed most obstacles to continued control both over the civilization’s development and its requisite resources. From there, the empowered class became entrenched.

There was scant evidence that the consolidation of power started with the brightest of the species and, even if it did, intelligence did not remain a selected-for attribute. The continued guarding of its inner circles — where nepotism or even inbreeding became a staple — led to a proportional shift: upwards of its hubris, and downwards of its compassion and wisdom. In short, deficiencies in all the necessary features of good leadership became apropos.

The ruling class recognized early its abundance of weaknesses, so the smarter of its membership turned its attention toward redefining what strength and weakness meant.

A tyrant should appear to be particularly earnest in the service of the Gods; for if men think that a ruler is religious and has a reverence for the Gods, they are less afraid of suffering injustice at his hands, and they are less disposed to conspire against him, because they believe him to have the very Gods fighting on his side.

— Aristotle; Politics, Book V (350 B.C.E.)

The war of truths

The value of information was not only in who possessed it but, more critically, who did not. To sustain a tenuous hold on unearned power, it was essential to find an unassailable justification. The ruling class needed to control something their subjects could never wrest away. Resources dwindled. Technology changed.

Over time, the answer became clear: information. But it was not state secrets that they worried over. Those were obviously stealable. No, they needed to know things—to be something—no one else could.

And so was born the system of god-favored men.

It was genius, really, though certainly not thought up by some cadre of villains in a smoky room. Divinity emerged as all mythologies do—fanciful efforts to answer questions for which none could immediately provide more grounded explanations. Prometheus’s gift explained fire until the mechanism of combustion was discovered. Zeus’s fury filled the conceptual gap until more astute observers came to understand the role of charge separation and field generation.

The beauty of mysticism was in its comprehensiveness. Any phenomenon’s function could fall within its purview. For as long as there remained unanswered questions, there remained divine explanations. But godly answers alone were not enough to leverage power. If anyone’s mythos could solve any mystery, then no advantage was to be had. Thus, to buttress power there came the need to ostracize any competing explanatory narrative.

Only one god or pantheon of gods could be real, only one storyline true. Regardless whether competitors derived their narratives from the same canonical lineage, only the preferred version and its associated directives were acceptable. Adherence to others constituted an affront to the power of those relying upon a certain tradition rather than a difference of philosophical interpretation.

In different places and times, different dogma reigned. But in nearly all large societies, just one enjoyed superiority at any given time, only succumbing to another when political power changed. The gods, it seemed, were indifferent to their own primacy.

The demand for singular obeisance served as the quintessential restraint on information. If just one doctrine constituted truth, then there was no need to study or even know of any other. The chosen doctrine became the subject of teachings, the message of missionaries, and the basis of law. Most importantly, it became the foundation of the right to rule.

Controlling the theocratic construct involved more than simply elevating one’s preference. The problem with rule that was justified by religious doctrine was that advancements in understanding undercut the prescribed teachings of the allegedly omnipotent deities.

When evidence-based comprehension of the world was in its nascent stages, the greater threat lay within the teachings themselves. Any explanation of complex matters that had been woven together by countless people over centuries — in different languages, with different agendas — was bound to be rife with contradictions or logical inconsistencies. Aristocrats themselves did not always agree on which texts from their shared canon applied to their version of truth and justification for authority.

So, at least as early as the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, powerbrokers in governments and religious institutions across the globe went to great effort to prevent their subjects from actually reading the very texts whose words were used to control them.

This did not always occur in a systematic or consistent fashion, but it dominated the trajectory of history for centuries. The purported written words of god(s) — esoteric as they may have been — were hidden away from the public or given only in “excerpts chosen to fulfill a particular ideological, theological, or didactic purpose.” When debates were held, they were typically conducted by appointed men; public participation came at great risk to the the uninvited.

But gods could not satiate the avarice of earthly rulers. They could not provide adequate creature comforts to the subjects of those rulers to quell dangerous discontent. And information could not be withheld forever. So, despite enduring great personal risk in many instances, the more enterprising humans took it upon themselves to upheave this paradigm.

They put the system of rule by arcane mysticism at considerable risk.

Purveyor of baubles. Photo by David Tip on Unsplash

“You have desires and so satisfy them, for you have the same rights as the most rich and powerful. Don't be afraid of satisfying them and even multiply your desires.” That is the modern doctrine of the world. In that they see freedom. And what follows from this right of multiplication of desires? In the rich, isolation and spiritual suicide; in the poor, envy and murder.

― Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (1879)

Out with the old, in with the new

Maintaining an iron grip on ‘truth’ suffered a catastrophic blow with the invention of Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden. Gutenberg, as he is now known, invented the movable-type printing press (MTP), which revolutionized the distribution of information. Like all major breakthroughs, his built on the work of many researchers and engineers before him, but the MTP’s function, timing, and uniqueness nonetheless made it groundbreaking.

Perhaps no further proof of the MTP’s threat to the aristocracy was Gutenberg’s choice for its first mass-produced text, Latin Bibles. For the first time, the masses had relatively easy access to prints of the book that for over a thousand years not only informed their belief system, but provided the basis for any number of atrocities committed by or against them on behalf of the ruling class.

Historians asserted that Gutenberg’s press was critical to the development of the Renaissance movement, which promoted the “genius of man... the unique and extraordinary ability of the human mind.” The Renaissance movement was not a wholesale rejection of religion, but it sparked a dangerous time for the governing class who ruled in its name.

In the disruptive period following, the ‘Age of Reason,’ many began to question religiously based authority. The content of the holy texts still permeated the beliefs of the vast majority of the populace, but while existential questions remained such that people still accepted the purported profundity of the canon, they could pursue answers without the subjugation of the divine right of kings.

A window of opportunity had opened. The time for new kings was nigh, but the security of their power and prestige required trappings that unequivocally differentiated them from the tyrants of yore. There was no turning back the clock on the dissemination of information, so the manifestation of any new dogmatic justification for control would need to be insulated from the catastrophe of exposure.

Instead of asserting authority through the fear of divine reprisals, the new cudgel took on a far more insipid form. Where once the admission into heavenly realms drove the populace, the next centuries birthed a new motivation: acquisition. The bauble became the new god, industry the new spiritual exercise.

There was little question that the Industrial Revolution initiated one of the most significant redistributions of wealth in human history. Unlike in the time of serfdom, workers received wages that provided them the ability to make expenditures not solely driven by survival. This was because starting in the 18th century, most saw consistent growth in income year-upon-year. However meager that growth was, it remained better than the rises and falls of the past.

In addition, the period led to extraordinary developments in technology, which helped reshape the very fabric of human civilization. The urban center overtook rural living as the principal cultural paradigm, and this created trends in all kinds of areas such as art, fashion, cuisine, and even language. Cultural competition opened the door to consumerism as growing numbers of people with disposable income sought to keep pace with the fashionable milieu.

On the heels of the Enlightenment, the explosion of new technology concretized the belief that humans possessed the most advanced intellect and reasoning skills among the lifeforms on earth. Their scientific and technological progression made them fully capable of providing more than the adequate amount of necessities for everyone to have an enjoyable existence. Violence, forcible deprivation, and other abuses should no longer be necessary for the proliferation of the species.

Unsurprisingly, the unscrupulous lot driven by the desire for power disagreed. They believed that they alone possessed the planet’s most advanced intellects, and they alone should decide who technology could enrich. To achieve this supreme authority, they needed to promote themselves to the top of the social pyramid. This would bestow upon them a modern version of divine right based on their ostensible individual superiority.

These so-called industrialists climbed their way to extraordinary wealth, supposedly through their brilliance and innovation, but as often if not more through “cornering and watering stock… political corruption and the bribing of legislatures.”

Whichever was the dominant feature — innovation or corruption — the robber barons, as many called them, did not abandon religious justifications for rule, they simply changed the nature of god. Andrew Carnegie, for example, wrote:

Material prosperity is helping to make the national character sweeter, more joyous, more unselfish, more Christ like.

Notably, the religiosity of Carnegie and his cadre of fellow criminals put their material prosperity above all else, and they were willing to invoke violence to defend it. They effectively laid the foundation for the theft from and murder of millions of people that persisted long after their deaths. As Professor Eugene McCarthy explained:

Aspects of corporate law and business education induce white-collar fraud, which costs the public trillions of dollars and kills more Americans than violent crime. This system arose when nineteenth-century robber barons captured legislatures, courts, and universities to empower privileged individuals to profit at society’s expense. John Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, and Leland Stanford transformed state laws and Supreme Court doctrine to enable antisocial commercialism. Capitalists like Joseph Wharton contemporaneously founded profit-centered business schools to normalize patriarchal economic exploitation.

Already, widescale destruction of the environment had begun with vigor and only grew worse during this phase of ‘modernization.’ Under the guise of progress, the new upper class exploited everything. They engaged in thinly veiled colonialism and absconded with local treasures, often leaving devastation in their wake. The resource powering this revolution shifted from water to coal. Pollution became endemic. With godliness contained within the shiny bauble, the entranced populace hardly protested as the skies above and water around them turned fetid.

Truly sophisticated thinkers—anomalies among the broader population—pointed out the chasm between the claim of human superiority and its application.

They identified the culprits, both systemic and individual, behind the creation of a tripartite division among their brethren—the haves, have-nots, and have-nones. They identified their motive—to hoard an unfair share of the planet’s bounties at the expense of those that the misfortunes of history relegated to the lower classes.

They described their modus operandi—advocate a mass delusion, one in which resources are supposedly limited to a finite pie that cannot accommodate all wants or needs. For this the perpetrators fabricated a hierarchy based on gratuitous, self-serving criteria that granted select members large slices, and left little for the rest.

Scarcity, as the idea came to be called, was the fundamental core of economic theory. The economic system that derived from it accelerated the notion that humans suffer from “non-satiation of desire.” For that system to function, and later thrive, it needed to endorse the myth that happiness—the obtainment of desire—can never be achieved without acquiring more stuff. It identified success as having more than another, and gave value to value-less things.

Humans came to tie their self-worth to this concept. They saw the destitution of others as a key mark of their own superiority, and not just economically. The comparatively higher volume of things possessed proved, in their broken minds, their supremacy in morality, culture, intelligence, and value.

But the power of this new dynastic endeavor was fragile. Carnegie and his ilk could not sustain it and pass their ill-gotten gains onto their silver-spooned progeny without developing a broader strategy to firmly entrench the new divinity above the old one.

Credit: CreationistGuy

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the founders of corporate exploitation and abuse laid a sturdy groundwork for their successors, but their actions also revealed that unabashed dominance would ultimately create resistance. Elitism necessarily situates the few against the many. In the monarchic era, raw power worked because populations were diffuse and typically small. Geography limited any potential collective threat. The transformation brought about by the Industrial Age changed that.

Technological development increased at an exponential pace, with little sign of stopping. It began to connect the world so effectively that soon geography would prove to be no barrier at all. As the global population soared alongside innovation, the supremacy of raw power began to wane. In just 60 years, the population grew by a factor of three. The self-declared elites were vastly outnumbered and facing an increasingly informed adversary. More people understood the concept of exploitation and fought against it. Workers’ unions became powerful competitors to the wealthy industrialists.

One thing the oligarchy learned from the labor movements of the latter 19th and early 20th centuries was that in this new era where information traveled swiftly and people had great capacity to come together, they cannot know when they are being abused. It seemed an impossible contradiction, but there were glimmers of hope from examples like Henry Ford, who made it very publicly known how well he paid his workers compared to his competitors.

Ford did not pay them well because of his beneficence or to ensure his workers could buy the very cars they produced. He did so because working at the Ford plant at the time was one of the worst jobs of its kind out there. Until his epiphany, Ford could not keep workers.

He was chiefly responsible for creating the soul-sucking workday—eight hours of slogging through repetitive tasks that ultimately destroyed the mind and body. But by obfuscating that degradation of humankind with high comparative pay, he effectively convinced people—perhaps for the first time—to volunteer to trade their lives for the ability to collect baubles. In effect, Henry Ford opened the door for consumerism to become the religion of the 20th century.

The days when stories of resurrective miracles or obscure moral parables still held some sway over society were all but over. People now had a taste for wealth, however small by comparison, and would inevitably want more. But powerbrokers did not care to share. They found themselves in need of yet another innovation, a novel tactic of oppression, a way to convince the populace to willingly accept exploitation and degradation in exchange for crumbs.

And thus, a new era began, prompted by the closing gaps between populations and bolstered by ever more sophisticated dissemination technologies.

Losing an illusion makes you wiser than finding a truth.

— Ludwig Borne; Gesammelte Schriften von Ludwig Börne, vol. 6 (1862)

The turning tides of the information war

Just as the Gutenberg press disrupted religious narratives in the 15th century, another revolution in the distribution of information problematized capitalist dogma near the end of the 20th.

The internet.

No one — not even Al Gore — invented the internet. It was a seedling of an idea that germinated into a behemoth. J.C.R. Licklider of MIT envisioned a “galactic network” of globally connected computers in 1962. With him at the head of its computer research program, DARPA took on the role of creating the foundation for the internet of the next century. By 1990, researchers developed TCP/IP. It overtook previous iterations to become the primary protocol that enabled cross-network communication among many entities, not just governments or research organizations.

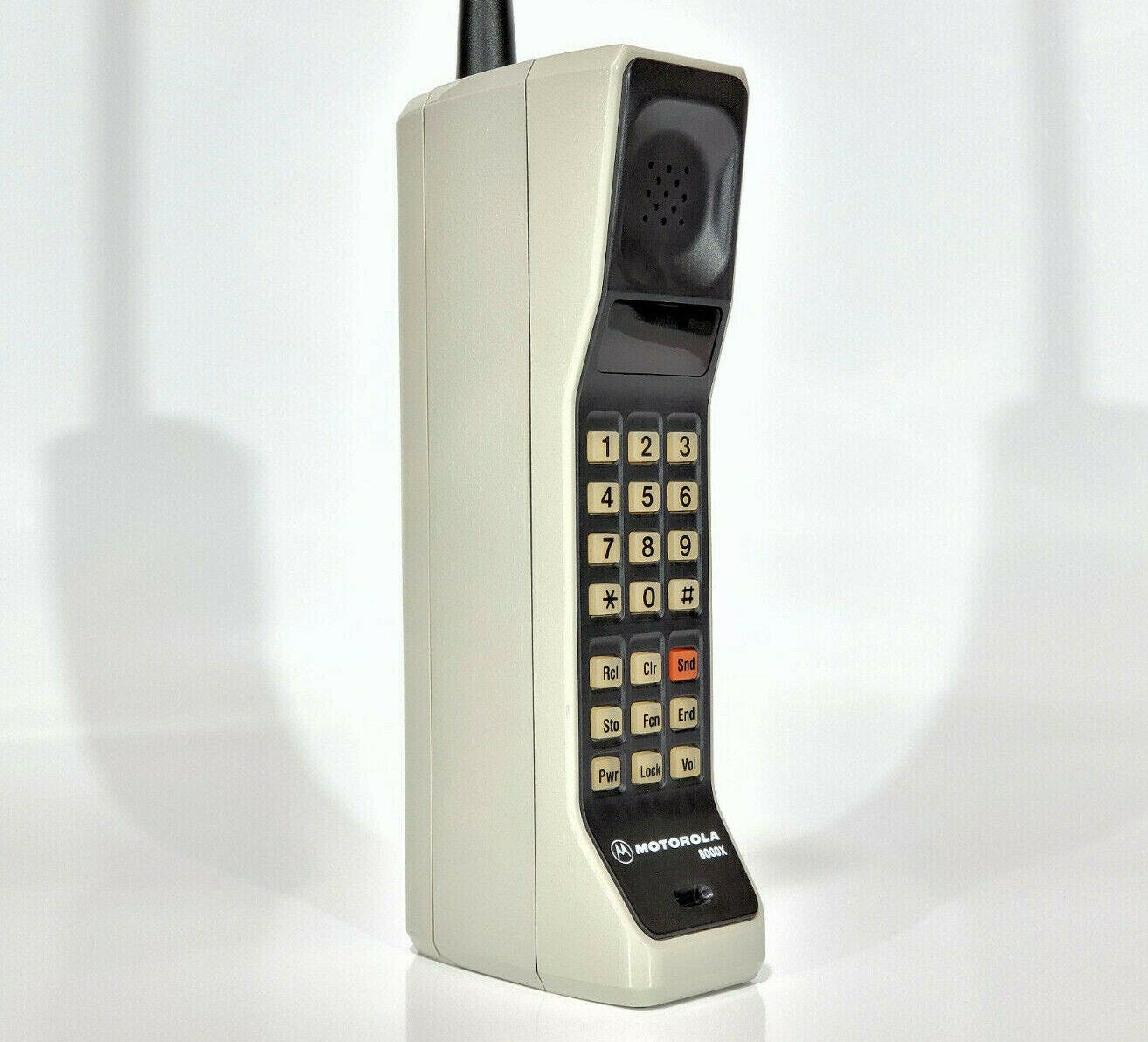

Other milestones ensured that the internet turned into a household commodity. Perhaps chief among these was the graphical user interface (GUI). This obviated the need to understand programming and command line functions and still operate a computer deftly. Browsers and URLs gave easy-to-remember addresses and a postal service to reach places across the world wide web. Handheld cellphones of manageable size replaced the old ‘bricks,’ and would soon provide a mobile connection to the ever-growing global network.

A Motorola DynaTAC 8000X popular in the late 1980s; source: eBay.

In its youthful days, the public internet was thought of as a ‘Wild West.’ As Steven Livy wrote:

[The Wild West internet] implied two things. First, the thrilling feeling of possibilities — anything goes, and that means even the most febrile imagination can not envision the opportunities in this virgin turf. The second was a scarier feeling that comes from the lawlessness of a territory too new for rules to be drawn. Anything goes, and that means you have to watch carefully for ripoffs and scams.

Early search engines like W3Catalog produced only raw results. Until 1996, there was no Google, and its first version was creepily named BackRub. “Optimization” and “Personalization” of search results came just a few years later, two tactics Google used to procure unmatchable dominance.

In 2007, Steve Jobs—who seemed to blame his own arrogance for his early death—introduced the iPhone. While Android phones overtook the market later, Apple provided much of the architecture to turn mobiles into an everyman product. Social media already existed by then, with about 5% of internet users in the US having an account, but the relative contemporaneity of those two things quickly started a new revolution. In effect, the so-called Information Age was about to go viral.

By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, the internet and particularly social media practically obliterated other outlets for obtaining information. Television had already put a severe dent into newspaper sales, starting in the 1950s, but did so with greater efficacy following the introduction of 24-hour cable news in the 1980s. As the internet eroded cable news’s grip, networks consolidated, carved spaces online, and turned to political pandering, with objective news comprising ever decreasing amounts of air time. Print papers all but vanished.

The attraction to opinion-presented-as-news may have prompted social media to become the primary source of news for most people. Surveys in the UK in 2020 showed that respondents spent an average of only 3% to 6% of their online time looking at journalistic sites. In 2022, one study found that 52% of users in the UK used social media for news. In America, 20% of people reported getting their news from “digital influencers” on social media platforms, and more than half from social media generally.

Unfortunately, the design of social media promoted the spread of false information and reduced users’ ability to discern what was true or not. In such an environment, whatever people wanted to be the truth became their truth, no matter how far removed from objective reality. The confusion and infighting among the public destroyed the unified resistance and effectiveness of collective bargaining and generated a new kind of disconnect, one not all that dissimilar from the geographic barriers of old.

Only now, the barriers existed directly within the heads of the exploited. There could be no upheaval against those in power because their duped supporters would fight against any cause, even those that benefitted them, if instructed to do so. The power class needed to do little more than ignite a new controversy, something easily accomplished with the bullhorns fully at their disposal.

They spread buzzwords that defined the lines of these ‘culture wars.’ They generated evil phantasms with pure lies or exaggerations of real, but isolated, events. They carved distinct ‘sides,’ as if existence itself was a zero-sum game between combatting ideologies. Most importantly, they deflected scrutiny away from themselves.

From there, they could sow distrust in the institutions and processes that allowed humans to thrive, the same that put the brakes on their own greed. Through continued haranguing, they persuaded many to believe that doctors, scientists, and academics conducted their craft with political or financial agendas, but they themselves did not.

In this way, powerbrokers discredited those correctly calling out their obvious frauds. Supporters were told to pretend that previous conflicting words or actions either didn’t matter or were faked, that tangible problems were not real or not as they seemed. In short, everything became as untenable as a conspiracy theory.

This had profound effects. Fear and stupidity, relics that should long before have been abandoned once the hard lessons were learned, drove attacks on the compassionate and intelligent. The trivial became critical, the critical became dangerous. Self-righteousness displaced careful deliberation. Quality gave way to quantity. Opinion usurped fact. Logic became an endangered species.

It was a house of cards waiting to collapse.

We've arranged a global civilization in which most crucial elements—transportation, communications, and all other industries; agriculture, medicine, education, entertainment, protecting the environment; and even the key democratic institution of voting—profoundly depend on science and technology.

We have also arranged things so that almost no one understands science and technology. This is a prescription for disaster. We might get away with it for a while, but sooner or later this combustible mixture of ignorance and power is going to blow up in our faces.

— Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (1997)

Enshittifying the future

Desperate to squeeze every last drop from the people, the swindler class proffered a new target of salvation—futurism. Like the fiction of heaven, a technological utopia was dangled to bedazzle the downtrodden into quietly accepting their pitiful station. After all, life was a mere waiting room that would be traded for paradise once the moment arrived.

The architecture for this wondrous vision was already in place, they claimed, and needed only a few tweaks to fully realize it. Drawing upon the whims of artists of previous generations, they gave it a name that breathed life into the fantasy — artificial intelligence.

This technological elixir would solve all the world’s problems, supposedly, though no one really explained how. That was because it was pure absurdity. Artificial intelligence was precisely what its name expressed: insincere, or not truly intended, intelligence. Just as assertions of divinely bestowed rule were nothing more than the manipulations of the immoral, so were the claims about this newfangled technological wizardry.

Built on decades-old technology designed for faster, more accurate computing and statistical analysis of large datasets, ‘modern’ AI simply exceeded old standards in the same categories. It was an upgrade from a Chevette to a Ferrari—still a car, albeit a better one.

Without its purported ‘special’ abilities, it could solve the world’s problems no more capably than any other tool. Regrettably, those special abilities were as real as Gandalf’s magic. Only with massive datacenters that stripped the land of natural resources could AI manage to imitate certain facets of human capability. And even then, it did so successfully only in the eyes of its devotees or the uninformed. Those not so easily hoodwinked could readily identify its flaws and failures.

AI could not think or reason, or solve complex problems that required creativity or flexibility. It wholly depended on troves of works stolen from humans to offer an inferior facsimile. Furthermore, it tended to emulate the worse aspects of its human contributors—political dogmatism, racism, conspiratorial or delusional thinking, and ignorance. Its infusion into so many commodities ruined virtually all of them.

When it wasn’t failing at what it allegedly should do well, AI was often not functioning at all. Its greatest proponents, the capitalists funding this latest con on the people, used real humans behind the scenes to give the appearance of equivalency or even superiority when the machine could accomplish neither.

Elon Musk—perhaps the most notable fraudster of that century—put people in robot suits or had employees control Chuck-E-Cheese-styled automatons remotely. Amazon’s “Just Walk Out,” a program that the company claimed was a:

combination of computer vision, object recognition, advanced sensors, deep machine learning models, and generative AI,

was really just 1,000 people in India “watching and labeling videos to ensure accurate checkouts.”

Eric Siegel, who taught graduate-level courses on AI at Columbia University, aptly summed it up:

AI is BS… AI is nothing but a brand. A powerful brand, but an empty promise. The concept of “intelligence” is entirely subjective and intrinsically human. Those who espouse the limitless wonders of AI and warn of its dangers – including the likes of Bill Gates and Elon Musk – all make the same false presumption: that intelligence is a one-dimensional spectrum and that technological advancements propel us along that spectrum, down a path that leads toward human-level capabilities. Nuh uh.

For a while, businesses jumped on the AI brand-wagon, vigorously inserting it into their advertisements and startup proposals, no matter how little AI was truly involved. As what happens with all shams, however, people grew discontented when the results never came. Pathetic last-ditch attempts by venture capitalists could not sway them.

Despite nearly a decade of trying, the majority of businesses failed to see a return on their AI investments. Even the biggest companies, those wishing to corner the market, saw tremendous losses. Governments began cracking down on AI hucksters, at least the ones who falsely claimed to use it to raise funds. Protecting investors was, after all, the primary purpose of governments in the 21st century.

To overcome their losses and realize their vision — one in which they ruled a world of machine and human servants who satisfied every one of their desires — proponents of futurism could not simply give up. More so than ever, they needed the continued spending of consumers and investments of the foolhardy to keep buying off craven politicians because they could not risk the power of governments run by the uncorrupted being aimed in their direction.

Advertisements emerged as a critical source of funds. Search engine results became real estate rented to the highest bidder. Platforms that sold subscriptions on the basis of being ad-free suddenly were inundated with them. Services meant to bolster creativity and give anyone a voice were overrun by heavily funded operations intent on acquiring the most views and ad revenue. Cellphones chirped with notifications designed to coerce users onto apps. Websites plagued visitors with relentless popups. Anywhere ads could be pushed was flooded with them.

What made ads so tantalizing was their targetability. As every function in day-to-day life turned digital, it allowed companies to collect endless streams of data about consumers. This wasn’t limited to the obvious places, such as websites or online stores; it included driving a car, walking into a physical store, or heating a home, among others. Spineless governments made no attempt to curtail the collection. Data-driven advertising was presumed to be highly effective and, therefore, highly valuable, but it came with the summary execution of privacy.

With capital flows secured, oligarchs next turned toward stifling resistance.

They made sure governments effectively held a monopoly on the use of force, governments they owned and profited from. Atrocities committed by states were sold as moral or necessary, while resistance to them was criminal. Those rebelling against even the most oppressive regimes — once labeled ‘freedom fighters’ — became terrorists.

Oligarchs convinced hundreds of millions of people to condemn killers motivated by the desire for freedom or equality, but champion the murderers who instigated their rebellion. But as the bodies piled up, especially of children, this became an increasingly hard sell.

Large swaths of a hypnotized public broke free of the spell and, despite the threat of lethal retaliation, took to the streets in protest. Angry masses decried the acts and condemned their perpetrators and co-conspirators. They saw through the excuses given, dismissing them for the corrupt farces that they were.

That was only the beginning.

Things fell apart all over. The enshittification of the future was in full swing.

For fifteen thousand years, fraud and short sighted thinking have never, ever worked. Not once. Eventually you get caught, things go south. When the hell did we forget all that?

—Mark Baum (channeling Steve Eisman in the Big Short ; 2015)

On the precipice

In the country home to the most oligarchs, a bullet ripped through the back of one of them, killing him there on the street. At the behest of the victim’s terrified peers, the government focused every one of its resources on finding the shooter — something it almost never did despite an average of 44 murders per day in that country. This crime was different, officials proclaimed. It “was a killing that was intended to evoke terror. And we’ve seen that reaction.”

Members of the public who had been victimized by the dead CEO’s company, and countless others who had grown sick of his class’s exploitative tactics, didn’t argue the point — just the moral justification for it. Comedian Bill Burr cogently described the sentiment:

You know what's funny, I was sitting there reading an article, and a guy was like, 'Oh my God, he's such a great guy. He had a wife and kids, and he's such a great guy.' And then you find out, he and the other guys he's working for are getting sued for $121 million for dumping a stock, and not letting the other people know. It's like, there's your motive!

On TikTok, someone added a touch of frosting:

Thoughts and deductibles to the family. Unfortunately my condolences are out-of-network. Sympathy denied. Greed is considered a preexisting condition.

And on it went.

Defenders of the oligarchs, especially corporate media, went on the offensive, pretending that this singular killing was a defect of ‘one political side’ while ignoring their own abundance of violent rhetoric and cheering of criminals or the reason for people’s disdain for the deceased. It was the usual divide-and-conquer strategy meant to turn attention away from what the act seemed to represent to many.

And it worked… for a while. Like every other newsworthy event in the 21st century, this one was more-or-less forgotten with the rise of the next controversy. In fact, governments and commentators operated this way purposely—keep the controversies flowing so the public cannot give any one of them sufficient attention—but few were as prolific as the United States government.

Its leadership, comprising an array of some of the stupidest people in political memory, said or did anything almost daily that in an even modestly rational world would have destroyed their careers. Some of their theatrics were contrived, but most were a product of a true absence of intellect or maturity. Members of the political minority condescendingly lectured about civility or ethics, despite their own storied history of acting without either.

In any case, the broken political environment meant few of them suffered any particular consequence. Ideological tribes favored ideological tripe.

Unfortunately for all of them, chaos across the globe was coming to a head. Environmental disasters cost billions, a figure that grew year-on-year, yet governments and insurance companies increasingly denied people assistance to recover. Crises in some parts of the world were waved off altogether. Deaths from them had substantially dropped over several decades between the 20th and 21st century, but the evisceration of scientific agencies focused on predicting and warning about pending emergencies, and the gutting of aid agencies reversed that trend.

Despite rampant xenophobia fueling draconian anti-immigration policies among the wealthiest countries, people still flooded their borders in an effort to flee the decay or abuses in their homelands. The continued exploitation by the so-called G7 and their corporate owners rendered many places unlivable, either because of devastated environments or violence supported by clandestine agencies chartered with stirring trouble to protect the mechanisms of that exploitation.

Politicians, oligarchs, and their shills resorted to the ages-old tactics of maligning and dividing, referring to refugees and immigrants as vermin who committed horrors such as eating people’s pets or whose goal was “to take us over.” They blamed the most destitute people on earth for the ills that they themselves caused. The supposedly compassionate supported immigrants, so long as newcomers didn’t settle in their neighborhoods.

But both positions became untenable. Rich governments and their financiers were the source of mass emigrations, and their citizens knew it. Even those motivated by contempt for the foreign or the impact on the value of their property began to recognize that absent substantial change, the problems would build.

Some sought to change things from within the system. They launched campaigns to vote out the worst of the cretins, in many cases running for office themselves. They boycotted products of companies led by openly sinister executives. They contributed to crowdsourced efforts to assist refugees and the poor.

Others declined to participate, insistent that the system was too crooked to be redeemable, that money ruled and the people comparatively had none. Instead, they adopted violence and other jolting tactics. Rulers called them terrorists, unsurprisingly, but resisters wore the moniker like a badge of honor.

The discord frothed until it erupted into a global civil war, first cold, then hot. Sides were drawn—again—ostensibly between those who continued to benefit from the capitalist system and those who did not. But politicians and oligarchs clouded the meaning of ‘benefit,’ effectively keeping opposing factions aligned by existing ideologies, with many left rudderless in the middle.

This led to divisions from top to bottom. Businesses advertised toward one faction or another, never able to capture markets across the aisle, which further divided people. Friends and family became enemies, their allegiance to political ideologies somehow more powerful than personal relations. School curriculums morphed into raw propaganda machines, an assembly line churning out fresh partisans. Attention to the calamities caused by the separation of classes drowned under the ideological schism.

Democratic governments swung like erratic pendulums, with each administration brutally exercising its power against its political enemies of the last while never solving any specific problem. Dictators in the most forsaken parts of the globe prospered from the chaos by selling their resources and people down the river to richer governments and mega-corporations.

Meanwhile, the world’s problems reached critical mass.

The dissolution of personal relationships led to an explosion of depression and anxiety. Suicides spiked alongside stress-induced illnesses. An eroding communal psychology fueled the rise of violent crime as people lashed out against real or imaginary foes with much more regularity, and often impunity, depending upon the target.

Rising temperatures paved the way for the proliferation of disease. Ancient pathogens found new life, released by devastated ecosystems and invigorated by people who rejected effective interventions, particularly vaccines. A deficiency of medical professionals and scientists reduced options for or availability of treatments. Many turned instead to snake oils promoted by con artists, some with official titles, and paid for it with their well-being or their very lives. A collapsing environment made a sick population sicker.

With regulations against industrial pollution essentially gone, natural resources became unusable or even dangerous. Waterborne illnesses and dehydration swept through the populace, killing hundreds of thousands. Farms lost whole yields, their water consumed by technology datacenters and other guzzlers. Heat domes and globally rising temperatures caused droughts, some on epic scales, that rendered entire regions infertile. Starvation became commonplace. The pace of the mass extinction of animals and insects exponentially accelerated.

The ecosystem was eventually wrecked beyond repair.

As disasters took lives by the hundreds of thousands at a time, then by the millions, other infrastructure crumbled. Already, the world suffered from a dearth of workers. In the years leading toward the end of the 21st century, countless couples stopped having children. They were simply unwilling to bring progeny into the dystopia nearly all predicted, but only some would admit had come.

With fewer youths to take their place, adults were forced to stay in the labor pool far longer, especially after social safety nets lost the last of their funding so governments could keep propping up corporate welfare and shareholder profits. But failing healthcare and the vicissitudes of aging made elderly employees mostly unproductive.

Machines managed some of the laborious tasks, but they also could not meet the minimum standards to keep society running. Electricity, privatized to enrich a few, failed regularly and sometimes for long stretches. Even when the lights stayed on, sorely underpaid and undereducated human techs could not correct malfunctions in reasonable times. Droves of robot repairers never came to fruition because they were overly reliant on the myth of artificial intelligence.

Companies without pliant politicians in their pockets went defunct. Mega-corporations filled the gaps with slave labor, often prisoners or the homeless, under government contracts that ensured their profitability. They cheekily called it the ‘Next New Deal,’ rather than the raw deal that it was for the majority, pretending that they were benefactors keeping communities afloat rather than the source of their decline. Regardless, scarcity became very real and widespread. So, too, did imprisonment and homelessness.

Forced free labor lowered the wages of those still clinging to normalcy, who somehow held onto a job, to the point that the middle class vanished. Bankers stole property under the guise of delinquent repossession, which they then re-rented through a form of serfdom. People could keep the same roofs over their heads if they spent more hours doing what was needed to keep the rich comfortable and satiated, while giving up any comforts of their own. If they did not, they only avoided compelled servitude by moving to the secret ghettos dispersed within the toxic ruins of shattered cities.

Life mirrored the plots of pessimistic writers of years past, whose books were banned under the premise of shielding people — especially children — from the ‘taboo’ or untoward.

In truth, rulers wanted to eliminate “thought patterns” that might fuel resistance. Both in print and speech, they adopted language intended “to diminish the range of thought… by cutting the choice of words down to a minimum.” When the minimum of words did not suffice, they simply changed the meaning of existing ones. Media, entertainment companies, and technocrats used their platforms to validate these linguistic distortions.

Still, no matter how they tried to obscure reality their efforts amounted to putting lipstick on a pig. Likening the pandemic of 2020 to the spread of a common cold failed to trick those whose loved ones succumbed to the disease. Similarly, redefining the apocalypse of the late 21st century failed to fool the legions of people starving or dying from poisoning or overwork. When forty years old once again signified old age, no amount of newspeak was going to win hearts or minds, even among the dumbest.

The most powerful scurried into hiding as the world crumbled. They barricaded themselves within their estates, hoarding dwindling food and water supplies. Simply stepping out on the street meant certain death if they were identified. Billions of people openly advocated the murder of anyone thought to be ‘elite,’ and they did not exercise circumspection in deciding who this constituted.

Prisoners in their own palaces, the ‘elites’ slowly shed any sense of loyalty. They routinely sacrificed their comrades when it was necessary to preserve themselves. Survival in their gilded halls required keeping a scapegoat at the ready. Despite controlling militaries and living behind super-funded defenses, they were vastly outnumbered. Although unified assaults were rare, when they happened they posed a clear and present danger.

At first, they chose the stupidest amongst their ranks for forfeiture. It worked for some time because wealth and power in no way correlated with intelligence, even centuries after in-breeding fell out of favor. Nepotism still ruled the day and rotten apples did not fall far from the tree. Options were, therefore, abundant. But blood begat blood, and soon the people demanded regular offerings. The overall numbers of the upper crust fell, which emboldened their vengeful subjects.

At the turn of the 22nd century, violence was the global currency and scarcity the chief economic engine.

Within a few decades, the human population declined so dramatically that class division fell with it. There simply were not enough people for some to live off the efforts of others. Civilizations did not cease to exist, but they no longer resembled their previous peaks, either in modern times or ancient ones.

Once you’ve arrived at the end of the world, it hardly matters which route you took.

— Isaac Marion; Warm Bodies and The New Hunger (2016)

The End

No plot twist ever came in humanity’s story. There were only two ways it would end.

One was the devolution of the species, a primeval shell of its former self, subdivided by external factors, exactly as Charles Darwin observed in others. For humans, this might manifest in forms similar to H.G. Wells’ Eloi and Morlocks. Once capable of advanced thinking, they would turn to living like their closest cousins, exhibiting sufficient instinct to survive in the wild and intellect to exact violence upon their neighbors when the mood struck them, but incapable of dominating their environments like they had in the past.

Perhaps eons later, history would repeat and give them another chance. Or, evolution would select for a different trait of dominance, rendering them either as eternal prey or so inconsequential that they would quietly go extinct.

The other possibility was their sudden and comprehensive extermination that, in their enfeebled state, they could no longer prevent. Whether by a natural disaster like a meteor or volcano, or a final self-inflicted wound like a nuclear holocaust, at the moment of its inception some would beg ancient deities for mercy that would never come. Others would refuse to acknowledge the reality even as their earthly hell overtook them.

Either way, their sordid legacy would be buried deep with the earth’s strata. If another lifeform in the universe who did not fall victim to the same vanity and foolishness happened upon evidence of their existence, it would benefit from the lesson these flawed creatures taught about the perils of division, short-sightedness, and the lack of basic sense.

If not, the universe would persevere as it always did, its secrets never unlocked by the one lifeform that had the opportunity to unlock them, an opportunity squandered by selfish pettiness.

In order to leave a comment it stopped and sent me an email with a six-digit code I had to put in first.

Reading it I wasn't sure which point you were trying to drive in this other than whoever is making things or changing things and inevitably new leaders come and change things some for it some against it. I think there's a lot more and a more simplified version because some of it you kind of lost me basically because I wasn't going to look up the word lol I know you're a vocabulary is huge. And I know you put a lot into this. I'll give you an A- 😉