Photo by Zachary Kadolph on Unsplash

In 2021, the World Economic Forum reported that “China could lose between 600 and 700 million people from its population by 2100” because of a “fertility collapse.” Many people assumed that it had to do with China’s infamous One Child Policy and the impact of the COVID pandemic.

But it turns out the phenomenon is far more widespread, both in place and time.

A study published in the Lancet analyzed global trends covering the past 70 years and found that:

By 2050, over three-quarters (155 of 204) of countries will not have high enough fertility rates to sustain population size over time; this will increase to 97% of countries (198 of 204) by 2100.

To put it more bluntly, people just aren’t having babies like they used to—pretty much everywhere. The question is: why?

Demographic Transition

In the past, low fertility was typically associated with wealthier countries. As economic and social conditions improved, there was an inverse relationship to reproductive productivity. Sociologists refer to this as ‘demographic transition.’ The specific reasons for the phenomenon are hard to nail down and likely vary among different cultures, but could involve any of the following factors:

more young people choose careers over children;

better healthcare improves survivability (so a family does not need to produce as many children to ensure at least some reach adulthood);

children are not needed to help sustain the family (through their labor);

raising children is extraordinarily more expensive than in the past;

lifestyle precludes the desire to rear children;

contraception is more widely available.

Seventy years ago marked the beginning of the period following the post-WWII transition — the point at which the Lancet study started its analysis. Many countries saw a wellspring of wealth and prosperity over the next couple decades. Better education, labor unions’ success at ensuring fair treatment of workers, and higher expectations from the citizenry forced wages ever upward in these places. Countries who ultimately benefitted economically endured declines in birth rates while developing countries saw rising rates.

But it didn’t last.

Business ownership began to shrink as massive corporations consumed competitors at a frantic clip. This was bolstered by technology and the banking sector’s financing tactics. Unions faced opposition, both by companies and by some of the public as corporate bosses launched campaigns to smear and defang them. As a result, the world has undergone an historically large economic schism, where a tiny portion now controls the vast majority of wealth and income.

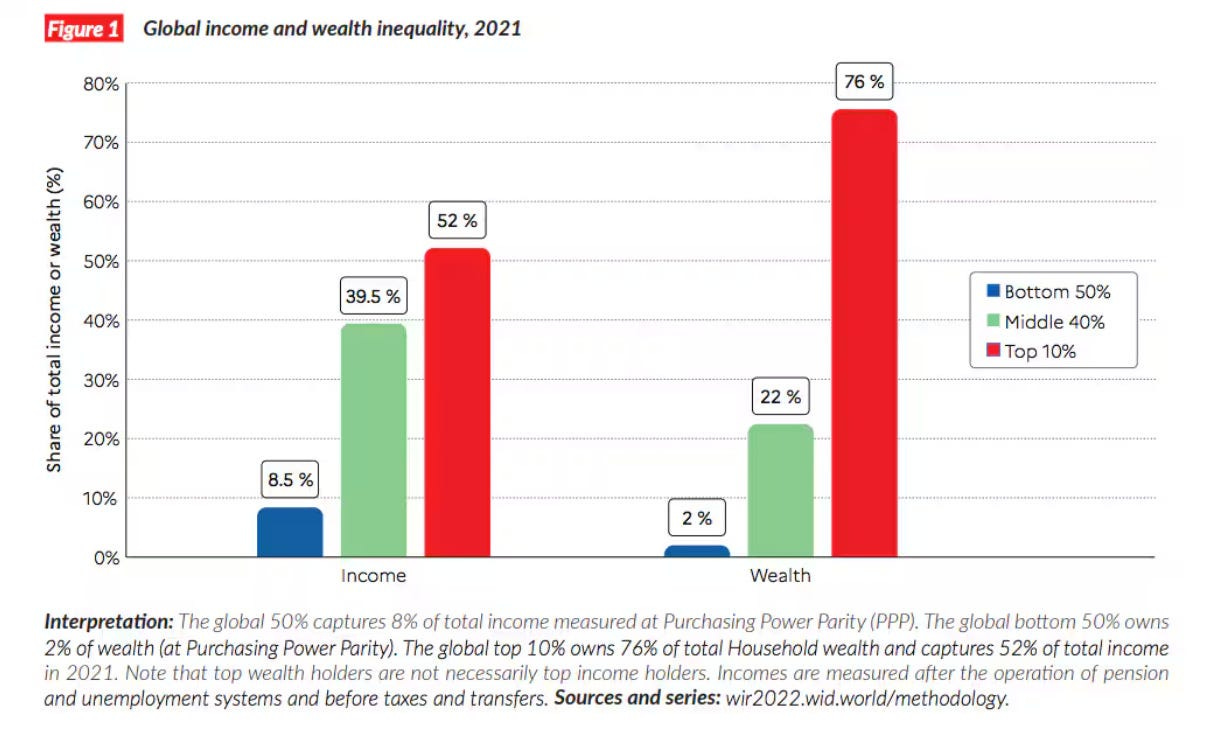

Credit: World Inequality Report, 2022

The divide is not just between the developing and developed worlds, however. In the graph above, the distribution of income and wealth is measured by the global population, but when broken down within the richest countries, the disparity is even more remarkable. Take a look, for example, at the United States since 1983:

Credit: Pew Research Center

Not only is the difference stark, but the gap is growing. The same is true in much of Europe, Latin America, and Asia. The data shows that inequality is growing between the top class and everyone else, not between nations or cultures.

Economic inequality leads to more than just a difference in living conditions. As companies and individuals amass wealth, they also amass power. It is not simply that big business can violate the law with impunity, it is that big business can make the law to its benefit. Roy Shapira, writing in the Cordoza Law Review, explained:

Super-large firms can wield their power to influence the regulatory framework that governs them so that their behavior falls within the law. When these firms nevertheless transgress the lines, they can water down the prospect of both private and public enforcement. They leverage their market power to sign their counterparties on class action waivers and gag clauses, thereby diluting private enforcement.

As for public enforcement, the fragmentation of knowledge inside these super-sized organizations makes it harder to prosecute top individual decision makers. And the firms’ systemic importance and big war chests make enforcers reluctant to vigorously pursue sanctions at the entity level, for fear of collateral consequences and the enforcers’ own reputation concerns.

From this, society has ended up with an environment that teeters on collapse. Wage theft is perhaps the most common and financially destructive crime. Products and services are undergoing widescale enshittification. Education is about producing workers, not enlightened contributors to the human condition. Everything is starting to feel like a scam, and most of it actually is.

Based on the trajectory of fertility rates over a much longer time period than the Lancet study covered, one might have expected to see birth rates shift upward as economic conditions took a turn downward in many countries, but that is not what happened. Instead, they continue to plummet.

The Global South

The Global South did not enjoy an economic ‘golden period’ like the Global North did. For clarity, the Global South refers to “spaces and peoples negatively impacted by contemporary capitalist globalization,” typically — though not always — areas that once were colonized by Western powers.

Neocolonial exploitation persists there, though among the public it is hardly talked about. The phrase refers to the mistreatment of societies by world powers that adopt some of the same tactics as colonial powers, but under the veil of modern capitalism and legalistic autocracy. The victims suffered long-term oppression from colonialism, neocolonialism, or both, and still struggle to be treated fairly economically, politically, or culturally.

An important aspect of this is the flow of cultural exports. To briefly explain what a cultural export means, consider the content of movies or books. Roughly 95% of them are created by and, to a lesser extent, targeted toward those who are “(a) affluent, (b) majority white, and (c) have historically benefitted from relationships of domination, including enslavement, colonialism, and conquest.”

This kind of hegemony reaffirms an historic hierarchy in which Western culture sits at the top and the rest are effectively positioned as ‘abnormal’ or ‘weird’ and, often, something to be ‘fixed.’ Moreover,

[it frames] the worldview of the ruling class, and the social and economic structures that embody it, as just, legitimate, and designed for the benefit of all, even though these structures may only benefit the ruling class.

Dominance over currency, particularly by the United States, has also contributed — even fostered — the continued subjugation of developing countries. In a detailed analysis of this issue, Ntina Tzouvala of Australian National University College of Law, wrote:

[W]hatever the role and potential of the dollar domestically, internationally, it operates as a form of despotic power. This can happen indirectly insofar as dollar dependency can curtail the monetary sovereignty of states. It can also occur directly, as in the case of financial sanctions that allow the United States to exploit dollar hegemony in order to inflict pain on its foes.

Likewise, technology has always been a powerful element in driving the inequities between the Global North and South, and the latest is artificial intelligence.

Studies have shown that transnational companies push for deregulation and engage in “labor outsourcing to regions with the lowest wages and weakest social safety nets,” often with the support of dominant governments. AI’s very success as a commodifiable product is heavily dependent on these tactics.

As Dr. Salvador Santino F. Regilme noted in the SAIS Review of International Affairs:

The human rights implications are profound: workers in these countries often perform monotonous, repetitive tasks that are essential for training AI systems, such as tagging images, reviewing content, and processing data. Yet, these workers are often rendered invisible in the global narrative of AI innovation, existing as “ghost laborers” whose contributions are exploited while they remain outside the frame of AI’s celebrated progress…

Energy demands are often offloaded to data centers in regions with weak environmental regulations, like the Global South. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have constructed data centers in Africa and Southeast Asia, attracted by cheap electricity and limited governance oversight. These centers worsen local environmental degradation and natural resource depletion in areas already heavily impacted by climate change.

While facing continued cultural, political, and economic mistreatment or exclusion, the Global South is also seeing some of the greatest negative consequences of climate change. Uncertainties generally have a profound effect on people’s choice to have children. Concerns about the stability of the future environment have added significant uncertainty to people’s broader outlook and are believed to be a major factor in the declining birth rates in many such areas.

When one’s culture is rejected by the rest of the world, the surrounding environment is collapsing, and the economic gains of the rest of the world are earned on the backs of their labor, it is no surprise that many are making the decision not to have children in such places.

Photo by Zac Harris on Unsplash

Failing to see the problem and, thus, the solution

Governments and big business almost always see declining birth rates as a problem. As fertility declines, the population undergoes a shift where the working-age class gets smaller while the retired population grows considerably. A dwindling supply of workers means that wages will rise and so will costs to government primarily to fund programs designed to take care of the elderly, like social security or Medicare.

The fear of suffering an economic hit has prompted many countries to take action to rectify this ‘problem.’ These include offering childcare subsidies or long-term paid family leave; launching fertility initiatives; giving out tax exemptions or subsidized loans; or even making IVF free for qualified mothers. Some places have tried what might be called a ‘conservative’ approach. They have banned contraception, or restricted or banned abortion.

For virtually all of them, these efforts have failed and continue failing. The reason seems to be rampant uncertainty, fueled by the public’s inability to pinpoint the real problems and, thus, develop effective solutions. Short-term incentives to have kids are simply not enough to displace anxieties about the long-term outlook.

Upheaval seems to be happening almost everywhere — the economy, regional and global politics, technology, environment, etc.

Despite an unprecedently large library available at most of the world’s fingertips, for many it has become much harder to discern what is true or to think critically about the arguments presented. They thereby target their ire at the nonsensical rather than real problems.

For example, anti-immigration sentiment has risen in many places despite the fact that immigration helps overcome some of the challenges associated with dwindling populations and has historically benefitted societies far more than hurt them.

Some insist on demeaning scientists and academia as if examining issues and proposing solutions is a greater transgression than causing those issues. Communities are splitting down political lines like their people are attending a football match rather than scrutinizing what the parties are actually doing (or not doing).

This has situated the battle for leadership of world governments between the corrupt and the brazenly corrupt. Vacuous populism is growing despite the utter inanity of the candidates and their supporters. And the citizens keep getting left holding the bag.

Using social media and other bullhorns, the rot at the top persists in infecting the populace. It has convinced people that virtually any measure to help their brethren is wrong — somehow — while handouts to the wealthiest continue unabated.

Through a deluge of bullshit — often daintily referred to as ‘misinformation’ — the powers that be have fooled some into believing that the historic climate disasters ravaging their neighborhoods are hoaxes or ‘normal’; that trans people are a greater threat to their children than religious institutions or unrestricted child labor; that the murder of a single, corrupt CEO is terrorism while committing genocide or deporting or imprisoning people without due process of law is not.

Views like these are repeated on social media ad nauseum. As real-world interaction is displaced by the trivial discourse there, hateful and ignorant views flourish and real-life social relationships suffer. The consequences of being despicable are simply less impactful when protected by the keyboard firewall, with or without anonymity.

The security of the family and friend circle continues to erode and the outside world is sinking into a pit of despair. Yet, a large part of the population cannot seem to identify the root causes. This has instilled a feeling of hopelessness, a worry that nothing will — or even can — improve. People are suffering unprecedented rates of anxiety and depression and, therefore, are declining to expose future progeny to this disastrous environment.

What prospective parents are saying

On Reddit, there’s a community called Fencesitter where people express their concerns over having children. The commentary reveals that the hesitance about reproducing is deeply personal and arises from a range of issues. But underlying the threads is one clear theme: that uncertainties about the future are substantial and often quite influential in the decision to forego parenthood.

This comment encapsulates the idea:

I am SO scared of making the wrong decision right now, and feel like my time is almost up for having a baby... I think of all that can go wrong, and if something happens to the kids, how is the world going to look like in 10–20 years ? What if I am not doing a good job? Do I have the skills to do such a huge job ? What if they dont have a good life ?

Others provide more specific reasons for their concerns:

- The environmental, political, and economic climates of the world all seem as though they will only become more hostile in the future. I am scared for what I will have to live through in 30 years, let alone what kids being born today will live through in the next 70.

- I save 10% to retirement for what lol. I fully believe the area of the country im in will be un livable before I pay this mortgage off.

- We are JUST starting the painful part of climate change. What we are seeing now isn’t the main event, it’s the dimming of the lights in the theater before the previews start.

- Climate change won’t affect everyone in the same way. I’m not really that scared of climate change per se for my children where we live. What I do fear is the political climate and maybe even wars that climate change might bring. That’s what makes me pause.

Among women, the uncertainties extend into the home itself. Professor Pragya Agarwal, author of (M)otherhood: On the choices of being a woman, notes that women today are forced to balance child-rearing with their professional lives in a society that does not consider the two equal. She says:

It’s fantastic that women are able to say, ‘this is the kind of life I want, I’m not prepared to compromise on that’, but some women are being forced to make this choice even when they want children, because the alternative is that they just take on all the burden, or they become mothers and then don’t progress in their careers. They don’t have the support in the workplace or at home, and they’re exhausted all the time: financially, emotionally, physically.

Eroding social bonds and increased economic obstacles are contributing toward a “negative momentum,” a term Penn neuroscientists Michael Platt and Peter Sterling use to describe a conflagration of soaring rates of sadness and suicide, as well as physical maladies.

This negative momentum means that some women are not physically or mentally well enough to choose motherhood. Those who are not so afflicted are forced to worry about the potential lack of structural support from the family and workplace once they have children.

Amy Blackstone, a sociologist who authored, Childfree by Choice: The Movement Redefining Family and Creating a New Age of Independence, concluded:

The pandemic has really revealed to us how poorly we support parents in the US. We’ve come to see the truth that we’ve always known but never speak out loud, which is that parenting is really hard. And we don’t really support parents in that role.

Concerns about raising children in an unsupportive social system are exacerbated by fears of the consequences of a collapsing environment. A study conducted in 2022 found that climate change is a significant factor in choosing not to have children in many places across the globe.

Source link: BBC

Julia Borges, a 23-year-old student from Brazil stated, “I cannot see myself as responsible for the life of another human being, for generating a new life that would become another burden to a planet that is so overloaded already.”

After visiting her home village that was ravaged by drought, Shristi Singh Shrestha, a Nepali animal rights campaigner, said, “Understanding how this world works, how climate change is changing lives for the worst, for animals and children — this realization made me cry everyday. It was pretty horrible to me.”

Nancy Madrid, a 34-year-old American, told Yahoo Life:

The climate crisis specifically brings me a lot of anxiety, especially as we have begun to see more of the impacts in wildfires, extreme temperatures and displacement of communities… So, if there was ever any real desire to become parents, it would be greatly outweighed by the fact that we feel we are currently unable to provide a safe environment and future for our children.

These kinds of sentiments are repeated by women everywhere, and are often shared by men.

What to do?

At a macro level, there are some obvious solutions. First, stop electing corporate sycophants. This is, of course, easier said than done because politicians of every party benefit immensely from big-money support both in their campaigns and in their lifestyles once elected and after their tenure. But that doesn’t mean the electorate can’t chip away at the problem. It requires work — one must be well-informed about a candidate’s history, not just the malarkey they say in front of cameras.

In the US, for example, choosing a self-proclaimed billionaire to be president, who speaks about being born rich like it was an achievement, ensured that a host of billionaires would occupy the top levels of his administration. And it has indeed come to fruition—he appointed a baker’s dozen of them, in fact.

Governments run by the super rich are not going to look out for the ‘regular’ people, as clearly evidenced by initiatives like America’s farcical “DOGE,” which has cut important programs for the middle and poorer classes, and fired numerous working class people, yet has not rooted out any real fraud or waste. Moreover, it has made cuts that will likely further embolden the rich, such as by diminishing the IRS’s ability to prosecute tax cheats who are overwhelmingly wealthy.

The wealthy class and corporations have also been among the greatest enemies of those seeking to find solutions to the degrading climate. For the former, their opposition stems from the fact that their opulent lifestyles contribute to climate change at obscenely higher rates than everyone else.

Oxfam International estimates that fifty billionaires emit the same amount of carbon pollution in 90 minutes as an average person does in a lifetime. The wealthiest 10% were responsible for half the world’s emissions — back in 2015. It is surely worse now.

Corporations repeatedly prove that concern for the environment is a business decision, not a moral one. When anti-climate administrations take power, businesses cower to protect their pecuniary interests. Aron Cramer, the president and CEO of BSR, a network of businesses dedicated to sustainability, explained:

Companies see a bully in the schoolyard, and they are off in the corner, doing their homework, and hoping the bully picks on someone else.

Shell Oil backed away from previous commitments to reduce its carbon footprint, saying it was concerned about “uncertainty in the pace of change in the energy transition.” BP flat out said it would rescind its previous commitments partly because of “the increased profitability” of oil and gas production.

Second, empower workers. Many people have succumbed to the idea that labor unions are bad. But in the United States, the golden age for the middle class occurred when labor unions were at their strongest. Ronald Reagan — possibly the worst US President for labor in the 20th century — sought to break them and workers have suffered ever since. His model for attacking unions and workers has been adopted in many places across the globe.

Workers need to come together and rebuild them en masse. This is especially important in regions where mega-corporations have engaged in systematic exploitation of labor and resources. It is possible anywhere, as content moderators proved in Africa. Governments across the planet are working hard to prevent this, which strongly indicates its potential for resetting the balance between workers and big business.

There is a grave concern about AI taking jobs. If this comes to pass, then society will need to undergo a far greater evolution than can be discussed here. In the meantime, however, unions can limit AI’s most destructive tendencies by forcing its regulation — something at which world governments are hopelessly failing so far.

Third, support and promote institutions and politicians seeking to mitigate the effects of climate change. While it seems hopeless, the worst effects of climate change can be avoided still, but not without serious effort. Electing politicians who call it a ‘hoax’ is certainly not going to move the needle in a good direction.

Aside from the power of the ballot, people have the power of the purse. Avoiding patronizing businesses that abuse the environment would have a profound effect if many people do it. Contributing funds to research organizations will help find and implement solutions.

Individually, adopting environmentally friendly habits serves two purposes. First, it tends to shift economic advantage toward businesses that are attempting to operate in a beneficial manner. Market forces are the strongest factor influencing the way companies conduct operations, so as people change their own habits, they tend to sway these forces. Second, over time it creates an unconscious shift in the public thinking about climate change, which will benefit all.

At the micro level, there is a rather easy solution, but it requires courage and tenacity to see it through. That is, individuals should stop forming strong opinions about things for which they have little knowledge.

They need to quit believing every ridiculous post on social media simply because it belittles someone they don’t like. They need to quit reading only headlines and assuming that they have sufficiently acquired information on the subject matter. And most importantly, they need to quit not-liking whole groups of people for trivial or even mythical reasons.

The reality is that most people are facing largely the same problems, all driven by the same root causes. And the culprits behind those root causes do not live on neighboring streets. Giving a person a break on student loans or inviting an immigrant population into a community is not creating the strife in the the lives of regular people.

Even a large proportion of crime can be attributed to poverty and its societal offshoots (like discrimination or poor education), the root causes of which can be traced back to wealthy elites and corrupt governments.

If you think the immigrant on the left is more dangerous to you than the one on the right, you are exactly where the powerful want you. (Image credits: CNN, MSN).

Women and men alike do not want to start a family on a planet that is enduring a tide of ignorance that pits regular people against each other while self-proclaimed elites plunder humanity’s treasures; where the avarice of a few is exacerbating natural disasters and intensifying misery for the many.

They do not want to start a family in a world where they get no financial or moral support; where government promotes reproduction as a panacea to systemic problems, but fails to create a legislative paradigm that will help ensure success.

Until the public can see what truly ails it, the problems will continue to worsen. Those who already have children will leave them an avoidable tragedy. Those who do not are rightfully hesitant to subject future offspring to such a mess.

This rising tide of dimwittedness and infighting is giving the worst people in existence the power to decide and execute their worst impulses. It will lead to a hopeless dystopia that brighter minds of the past have warned about for centuries, one in which almost no one will want to introduce new life. Right now, it seems that the global population has already accepted this as inevitable and has simply given up.

If you found this essay informative, consider giving it a like or Buying me A Coffee if you wish to show your support. Thanks.