Visit the new Evidence Files Law and Politics Deep Dive on Medium, or check out the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here. If you enjoy my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thanks!

Meet Alice Augusta Ball. She was the first woman, and first African-American, to receive a master’s degree from the University of Hawaii Mānoa (U.H. Mānoa).1 She also performed one of the most remarkable achievements in medicine, over one hundred years ago. Yet, you have likely never heard of her.

Source: UW Tyee Yearbook, 1911-1912

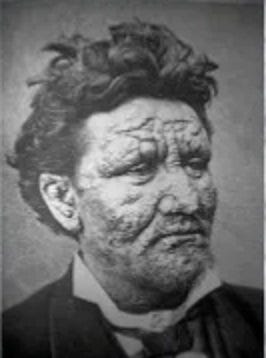

In 1866, the United States government established a leper colony in Kalaupapa, Hawaii, called a leprosarium. Leprosy, now known as Hansen’s Disease for the discoverer of its bacillus, is caused by an infection from a bacterium called Mycobacterium leprae. Today, it is curable if caught early enough, and treatable if not. But prior to the early 20th century, the disease caused blindness and crippling deformities usually of the hands, feet, and sometimes face, often caused by subsequent infections resulting from a diminished immune system. Even now, scientists do not understand the precise mechanism of transmission of leprosy, but the disease is quite contagious. Because scientists back then knew it passed from human to human, but did not know why, a diagnosis meant a lifelong exile to places like Kalaupapa. And once infected, one could hardly hide the fact. Moreover, not only did the government force victims to go to these leprosariums, it was no secret that “you were brought [there] to die.”

Kalaupapa colony, 1922.

It is hard to adequately describe the scourge of leprosy. Virtually unchanged since medieval times, the disease sprang up from time to time causing significant public outbreaks. For much of its thousand-plus-years history, people believed the malady represented an “expression of the wrath of god” and thus left priests to deal with it. As sufferers of leprosy typically depended upon priests for survival, when the Black Plague ravaged the priesthood in 14th century Europe, vast numbers of lepers starved to death. That was due in large part because society assumed that those who contracted leprosy were essentially sentenced to death, and thus shunned them to isolated colonies like that of Kalaupapa, or to homelessness outside of society to avoid spreading the infection. From the 1300s to the early 1900s, most leprosy patients lived squalid, painful lives in near total isolation until their deaths.

Leprosy victim, ca. 1886. Used under Creative Commons license.

Alice Augusta Ball would change all of that. Having earned her undergraduate degree in pharmaceutical chemistry at the University of Washington in 1912, Ball then co-published her first paper on Benzoylations in Ether Solution in 1914. That same year she finished her second bachelor’s degree at U of W. On the success of her first publication, Ball earned a scholarship to U.H. Mānoa to pursue her graduate degree. Later, in 1917, she published again in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, the first African American female ever to do so twice.

Ball returned to Hawaii, where she had lived briefly as a child, to begin her master’s degree program in 1915. At U.H. Mānoa, she studied the Hawaiian ‘awa root, called kava. In modern medicine, kava is used to alleviate anxiety. Hawaiians traditionally ground the plant into a drink imbibed during ritualistic ceremonies. Ball was testing it for its medicinal qualities as an injectate. Having isolated its component parts, her research determined a method for making it injectable without the usual skin abscesses previous efforts had caused. This caught the attention of Harry T. Hollman, the medical director of the Kalihi Leprosy Hospital in Hawaii, who was exploring the application of chaulmoogra oil to the treatment of leprosy. Hollman believed that, based on her thesis on kava, Ball could also develop an injection using an extract from chaulmoogra to more effectively treat leprosy. At 23 years old, Ball did just that. The University of Hawaii offered her an instructor position in chemistry as a result, another marked achievement at the time.

Ball’s solution was so effective that by 1918, seventy-eight people presented completely free of lesions and were actually discharged from the Kalaupapa colony, an unprecedented occurrence. Unfortunately, Ball did not live to see her success. In 1916, she died at the age of 24, possibly from tuberculosis. Nevertheless, between 1919 and 1923, no more leprosy patients went to Kalaupapa. They instead were treated in Kalihi hospital and released using chaulmoogra injections. Ball’s treatment mechanism remained in use until the 1940s when antibiotics took over, but its widespread application basically shut down Hawaiian leprosy colonies altogether, ending a very sordid chapter in America’s history of medicine.

As often happened to women in those days, Ball’s achievements were stolen by Arthur L. Dean, the president of the University of Hawaii Mānoa. Dean repackaged Ball’s work into his own, calling it the “Dean Method” and published it in the Journal of the American Chemical Society in 1920, with no mention of Ball at all. Hollman apparently took umbrage with Dean’s theft, publishing his own paper in 1922 titled, “The Fatty Acids of Chaulmoogra Oil in the Treatment of Leprosy and Other Diseases.” In it, he referred to “the Ball Method” and asserted that Dean’s paper showed “no improvement whatsoever” on Ball’s work.

Despite Hollman’s noble attempt to keep Ball’s name alive in the scientific community, her contribution largely disappeared from the annals of science until about 1997. Then, a man named Stan Ali discovered a vague reference to Ball during his research on the African American community in Hawaii. That reference, found in a 1932 work titled “The Samaritans of Molokai," by Charles Dutton, only noted some remarkable research conducted by a “young Negro chemist.” Coincidentally, three staff members of U.H. Mānoa stumbled upon Ball’s name while working on a comprehensive history of the university around the same time. Upon collaborating, Ali determined “to make sure you [Ball] get the recognition you are due.” Further research suggested that Ball’s race—both as an African American and a non-Hawaiian—her gender, and Arthur Dean’s academic dishonesty all contributed to essentially burying her deep within the shadows of the historical record.

Finally, in the year 2000, U.H. Mānoa placed a bronze plaque on a chaulmoogra tree on its campus in recognition of Ball’s work. At the commemoration ceremony, Governor Ben Cayetano proclaimed the day as Alice Augusta Ball Day. In 2007, the Board of Regents of the University of Hawaii posthumously awarded her the Regents Medal of Distinction, its highest honor. Paul Wermager, whose research played a significant role in uncovering Ball’s story, established an endowed scholarship in her name at U.H. Mānoa. The scholarship provides support to students seeking a degree in chemistry, biology, or microbiology. While Ball’s work may have gone long-forgotten, hundreds of people afflicted with leprosy had her to thank for a return to normalcy from their previously shattered lives, even if they didn’t know it. Although a century late, at least Ball’s remarkable work is finally receiving some of the accolades it has long deserved.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement. Today I work both in the United States and Nepal, and I currently run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas. For detailed analyses on law and politics involving the United States, head over to my Medium page.

Read about the feats of a legendary mathematician, Genevieve Grotjan Feinstein:

The word is often written as Hawaii or Hawai’i. The former spelling reflects the Romanization of the local spoken language developed by Catholic missionary translators in the late 17th century, who did not adequately represent the glottal stop (‘okina) now indicated in the latter formulation. To keep consistent, I used the traditional Romanized version. For more on the subject, see here.

Amazing I always wondered who cure leprosy. It is such a shame she left so young I wonder if she would have kept living how many other cures she would have made.