Flat Earth is a Microcosm of Big Tech Futurism

Emotional fragility, vapid promises, and the hope for a comeuppance

Image by author

People on a daily basis are spewing out all sorts of delusional pantomimes to try and justify it when all you really need to do is just stand by what is and in doing so the pain and suffering comes to a very abrupt ending.

— Level Earth Observer (YouTube)

Level Earth Observer, a YouTuber who claims he is ‘not’ a flat earther while simultaneously building a 12k+ subscriber count by spewing a great deal of flat earth nonsense, made the above statement during a live stream with SciManDan, a YouTuber and conspiracy theory debunker. Level Earth Observer’s “delusional pantomimes” referred to the way people employ scientific principles to debunk flat earth. Nestled within his outburst, however, was a very keen insight that he probably did not intend to make.

When you watch a flat earth video, you cannot help but feel dismayed by the level of ignorance it requires to accept the premise. Even if one can dismiss online imagery, the statements from astronauts or pilots, or the Antarctica Cup Yacht Race (that circumnavigates the continent), other very basic concepts utterly demolish the idea.

That these videos exist and their creators exhibit some earnest in making them leaves you wondering: what gives? Is our education system so broken that adults still debate a thing that scientists and mathematicians disproved millennia ago?

Well… yes, to some extent.

The problem, though, is not so straightforward that we can lay blame solely upon our mathematics and sciences departments.

Emotional versus intelligent belief

To keep this article to a reasonable length, I will not explore the very long history of scholarship on this dichotomy — I have written about it in some detail already. In summary, the issue comes down to understanding versus wanting. Con artists, politicians, and marketers thrive on elements of the latter.

Marketing and scams both work so well because they convince their marks to do something without really thinking about it. For fraudsters, especially, the task requires a strategy of longevity because if at any point their victim spends enough time pondering the pitch and thus uncovers the deception, the consequences are likely to be severe. Big Tech, flat earthers, and certain ‘futurists’ have all adopted the fraudster approach.

The not-so-hidden secret behind the strategy is to embed an emotional commitment into the acceptance of a premise. It is why, in the hundreds of interviews I conducted while in law enforcement, the hardest ones involved convincing fraud victims that they were in fact victims.

In Level Earth Observer’s case, if the “globers” (their silly word, not mine) simply concede that flat earthers are correct, the ostensible intimation is that the globers will no longer feel the pain of being humiliated by flat earthers. They will no longer suffer the constant revelations of their millennia-long gullibility.

What Level Earth Observer did not intend to illustrate is that this emphasis on emotion is precisely what drives adherence to nonsense in the first place. It is what earns him subscribers.

There is an innervation implanted within the message that suggests that people who know very little will eventually enjoy their moment of intellectual superiority. Level Earth’s audience is tacitly instructed to merely wait for their aha! moment when the globers finally come around. On that day, the flat earthers will be vindicated and elated.

There is an innervation implanted within the message that suggests that people who know very little will eventually enjoy their moment of intellectual superiority. Level Earth’s audience is tacitly instructed to merely wait for their aha! moment when the globers finally come around. On that day, the flat earthers will be vindicated and elated. Thus, the long game begins.

Constantly pushing the emotional narrative, the grasp for a moment of intellectual superiority, overcomes what rational thinking would readily eviscerate. For example, it allows a car mechanic to presume a deeper understanding of vaccines than an epidemiologist. It allows people to gravitate to something so fundamentally preposterous as flat earth.

Big Tech mouthpieces, venture capitalists, and so-called futurists likewise target emotion to garner acceptance of their own vaporware promises. They are, in effect, selling the equivalent of flat earth to anyone who will buy it.

Vaporware

The term ‘vaporware’ started with the computer industry, but generally describes a product or technology that “is late, never actually manufactured, or officially cancelled.” In short, it is hype that fails to materialize in any meaningful way, including development that falls far short of expectations built on pie-in-the-sky promises.

Lately, it comprises much of what drives the stock market. Examples include almost anything hawked by Elon Musk, AI, quantum computing, carbon capture, self-driving cars, LLMs, etc.

Each of these companies profited early from having “AI” in their name. Other companies publicly announced the addition of AI to their own services — no matter how irrelevant — or added AI to their names to achieve similar spikes in the months following. Sourced from thereformedbroker.com

For emotionally uninvested people, hype is easily identifiable. Promises made simply exceed any reasonable timeframe, outcome, or reality. Think of Marc Andreessen’s claims of AI “saving the world” or Michio Kaku’s assertions about the “quantum computing revolution.”

Both have been saying the same thing for some time now, yet AI is doing quite the opposite of “saving” anything, while quantum computing is nowhere near even provincial application despite huge investments in it that began over a decade ago.

Self-driving cars are another — possibly the most visible — example. Elon Musk said of full self-driving (FSD) Teslas in 2015, “we’ll be there in a few years.” By 2017, he was saying that FSD cars would be ready that year, which he then would repeat just about every year since.

In an email sent to customers in just the last month or two, a person or persons from Tesla wrote “At our We, Robot event, we unveiled the future of autonomy. Now, you can experience a part of the future for the next 30 days with a Full Self-Driving (Supervised) trial in your own Tesla.”

In reality, the We, Robot event was plagued with technical difficulties and a lot of apparent fraud — perhaps participants were in fact experiencing “a part of the future,” but not the one they want or expect.

The word “supervised” is constantly added to its claims because Teslas are no nearer to FSD than they were last year, or the year before. Indeed, a video released in July of this year showed the “FSD” Tesla driving on the wrong side of the road.

It has been a decade since Musk’s first assertions about fully automated cars. The company has been taking people’s money for this feature for quite awhile. And these systems still can’t tell left from right, among other important things, something Tesla lawyers admit in court even while Musk publicly proclaims otherwise.

Vaporware relies on still another kind of emotionally driven hype: that its promoters are visionary geniuses who can see or understand things the rest of the world cannot (and thus we should uncritically believe their claims and buy their junk).

Desperate for the ‘commoner’ genius

Assigning brilliance to those who exhibit barely none arises from what I call the ‘Good Will Hunting effect’ (my apologies if someone has already coined the phrase). For those who are unfamiliar, Good Will Hunting was a 1997 movie starring the late-great Robin Williams, Matt Damon, Minnie Driver, and that annoying guy who played Daredevil. Damon played Will Hunting, a rough-and-tumble fella from the streets of Boston who also happened to be a genius.

Will could look at a chalkboard containing confounding math problems, set aside his janitor’s mop, and solve them when even Ivy League mathematicians could not. He could instantly recall passages from archaic texts, including specific page numbers. He had limited or no education, swore and fought a lot, and primarily used his intellect to avoid criminal convictions and pick up women. His character was the quintessential display of the lone, unorthodox genius.

It is an absurd depiction.

The idea appeals to people who want to believe that ‘true’ genius requires no work; that some people are so super-duper smart that they just know things no one else can. Those clinging to this belief are easily persuaded by any level of bullshit paraded by charlatans who can weave a deft-enough narrative that preys upon their underlying laziness.

Reality, unfortunately, works very differently.

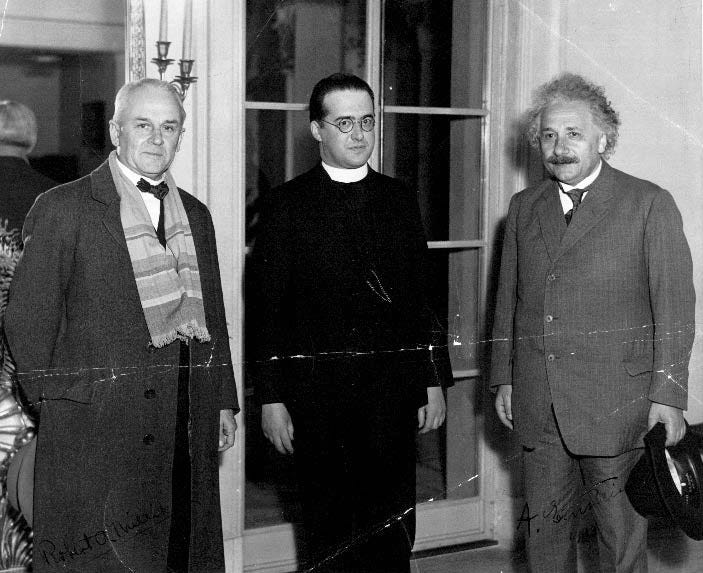

People who buy into this nonsense would probably label as geniuses of this type figures like Albert Einstein, Isaac Newton, or Mozart. But even those people — as bright as they unquestionably were — did not magic up the things that proved their exceptional intelligence overnight or in a vacuum.

Newton, for instance, spent decades laboring over the math and logic that would one day manifest as calculus. Einstein’s Relativity built off of centuries of work by earlier and concurrent physicists and mathematicians (and no, Einstein was never bad at math). Mozart, who by all accounts possessed unparalleled talent, nevertheless learned music from his father.

Humanity’s body of knowledge evolves much the same way as the physical species, over time and in response to external cues. These external cues comprise both contemporary and historical problems, as well as contemporary and historical efforts to solve them. Solutions require knowledge that is not intuitive — i.e., it must be collected over long periods of time, then generationally taught. True geniuses work for their acclaim — hard.

And in an increasingly complex world, what must be learned is ever more complicated and difficult.

Learned, not inherent, geniuses. Robert A. Millikan, Georges Lemaître, and Albert Einstein at the California Institute of Technology in January 1933. (public domain)

Lazy solutions

People gravitate toward self-proclaimed geniuses because they offer an easy way out. If alleged techno-wizards can come along and rectify all the woes of the world without the rest of us having to exert any effort or sacrifice in any way, is it any wonder why such people make billions of dollars duping investors and the public at large?

But thinking about how to responsibly build and rollout world-changing tech is much harder than developing a half-assed LLM that only looks like futuristic magic because it uses cheats (like huge, arguably stolen, training sets). Marketing cheats as magic ad nauseum serves to sell the illusion, but after a time the failures of vaporware become too apparent to ignore. Solving major global problems will never happen through a strategy of sell garbage until it becomes a product that works.

I keep beating this drum, so I will only say it again briefly here, quoting from a piece that I wrote previously discussing the same problem in the political context:

Far too many people are filled with hate because doing the right thing, and solving problems is hard. It requires collecting information, thinking about complex topics, and compromising on close-call issues.

Pretending there is a magic button to cure the ailments of the world is infinitely easier — whether Alpha Pills or ‘alpha’ politicians. Such fantasizing does not require any action or follow-through. It does not require thinking. It does not require any effort whatsoever. Accepting mediocrity, be it in entertainment or politics, is more desirable if no one has to lift a finger to change it.

And what we’ve gotten from the tech world lately is unquestionable mediocrity.

Solutions

My own family and friends sometimes accuse me of excessive pessimism. For their sake, I hope they are correct. Nevertheless, identifying a problem is only half the process. Lest I fall victim to my own complaint, here are some potential solutions.

First, the way we teach the young to critically think has to change. Even among the youth in my own circles I see the tendency to quickly accept interesting or seemingly ‘fun’ ideas, no matter how flawed they are. The adage “if it’s too good to be true, then it probably is” is almost anachronistic in our current times. Providing better guidance on managing emotional intelligence is essential.

Perhaps a necessary preemptive step is focusing on grown-ups. I cannot shake the imagery of adults — allegedly mature humans who, almost to the individual, were taught as children to cover their mouths when they cough or sneeze — screaming at the top of their lungs in public about having to wear masks during the pandemic. Clearly, our education on engaging in thoughtful deliberation has failed them, too.

Like this guy. Screenshot from a video posted on NBC News.

Without critical thinking skills, the populace too easily succumbs to the constant parade of bogus promises made by Big Tech elites. Instead of preventing serious problems by identifying flaws ahead of time, the tendency seems to be that millions of people dive headlong into a new platform or tech and only learn the hard way all the ills that come along with it. We are seeing this with AI and LLMs in particular.

For a case in point, see here.

Second, we need to apply greater emphasis on teaching the limits of technology. On this I mean from as much of a philosophical perspective as a technical one. This would include exploring previous tech hypes that amounted to practically nothing, or at least only very long-term change.

If we did this, perhaps the officials in Las Vegas who greenlit Elon Musk’s hyperloop — an idea discarded numerous times over the last century — would have opted not to waste hundreds of millions of dollars on a glorified tunnel full of slow-moving Teslas. Maybe we would have prevented the desecration of low earth orbit long before allowing its current crisis to develop by encouraging the funding of ground-based internet instead of its inferior sibling — satellite internet. And so on.

Finally, voters need to start demanding that societal goods belong in the hands of the people who pay for and depend upon them. Like healthcare, pervasive, world-altering tech should not be controlled by profiteers. I have pontificated on this at length in the article linked below.

The world is facing many significant turning points. More than eight billion people’s fate currently rests in the hands of a tiny cadre of lords who have expressed virtually zero interest in the general welfare. This is a recipe for disaster. Instead of one day enjoying a legitimate futuristic utopia, we might be left with a choice between endless suffering or jumping off the edge of the flat earth. I suppose if that day comes, we will all happily acknowledge that the Level Earth Observers of the world were right all along.

Why Private Capital is Bad for the Future of Tech

Example of a quantum cryptosystem layout; (Public Domain)

* * *

I am the executive director of the EALS Global Foundation. You can follow me at the Evidence Files Medium page for essays on law, politics, and history follow the Evidence Files Facebook for regular updates, or Buy me A Coffee if you wish to support my work.