Writing Good Science News Headlines is Hard, But Critically Important

Unfortunately, this is not a priority for many in this TL;DR society

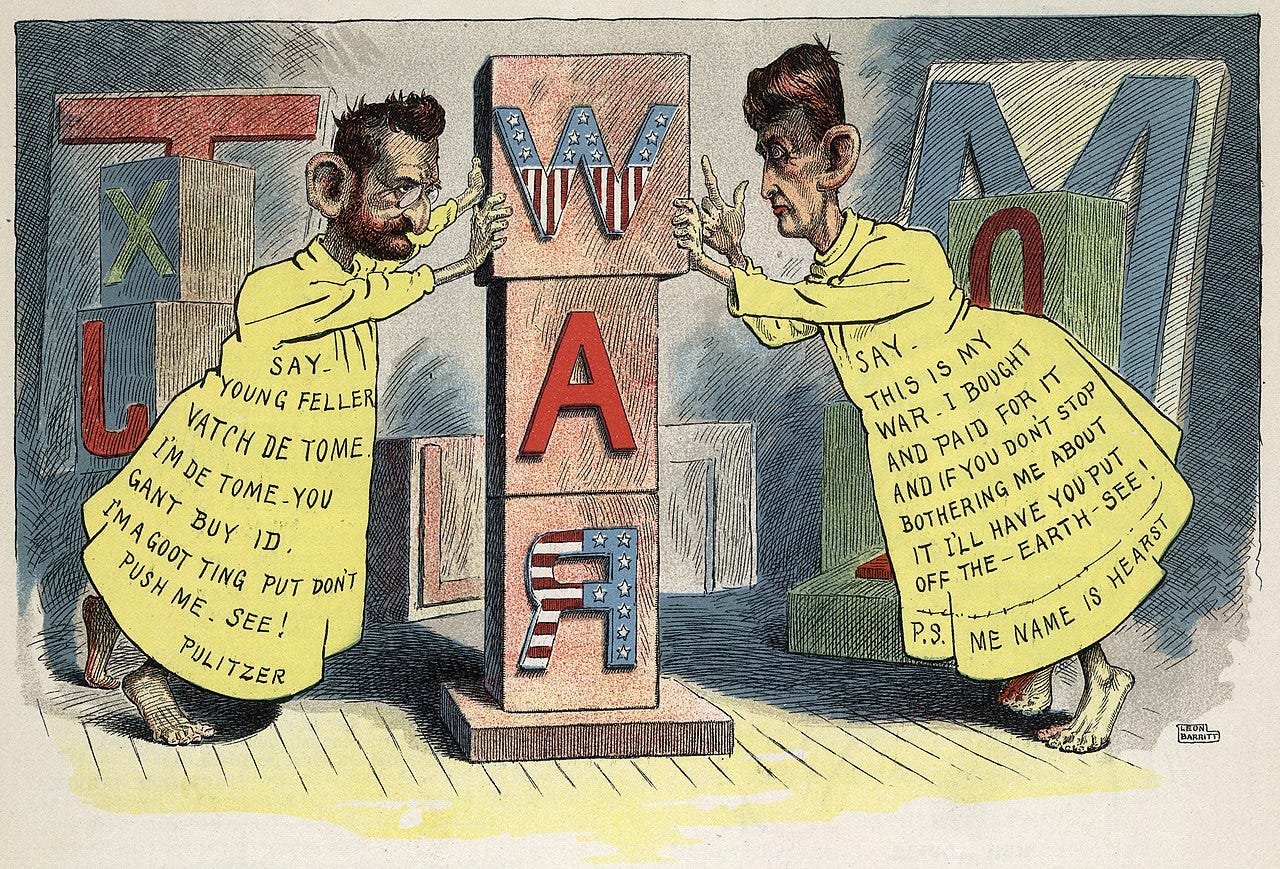

"Yellow journalism" cartoon about the Spanish–American War of 1898. Cartoon by Leon Barritt, first published in "Vim", v. 1, no. 2, 29 June 1898. (Public Domain)

Journalism outlets have no excuse for introducing stories with misleading or false headlines. They employ people trained in the art and typically have many sets of eyes to review material before it is published. That so many tend to use the tactic is an ethical failing.

Blog writers like myself have a responsibility to title their pieces with honesty and accuracy as well. It is perhaps more forgivable when we fall short at writing good ones, however, because most of us do not have editors or training in how to write a good title or headline, and it requires a decidedly different skillset than research and writing content. Nonetheless, there is no justification for using obvious clickbait.

There is no question that when it comes to educational articles, the topic matter is often complex and cannot be easily distilled to just a handful of words. Finding the balance between provoking interest and remaining true to the substance is in no way simple. But it is critical that publications put forth the most strenuous effort to achieve that balance.

In the 21st century’s TL;DR (too long; did not read) society, headlines have as much—or more—influence on what a large chunk of the public believes as the content itself does. If a writer or publication truly seeks to impart accurate information, then properly titling a piece is as crucial as ensuring that the content is appropriately sourced and correct.

Yellow Journalism

The use of “eye-catching headlines and sensationalized exaggerations” to sell news is hardly new. Sometime in the 1890s, media critics coined the term yellow journalism to describe the phenomenon. During that and subsequent decades, many newspaper magnates left the business of objectively reporting world events and turned to disseminating any level of nonsense that would inflame the public and raise sales.

When clicks and engagement rule the day, it seems the content of the article hardly matters. It’s all about the headline. This is evident in reading the comments on any story with a provocative lead. For example, I came across this piece when researching a topic on cell regeneration:

“Brought back to life” certainly sounds like a rather “shocking scientific achievement.” But, the headline is—unsurprisingly—false. Or, in the most generous reading possible, it is highly misleading. Even the lead author of the study quoted in the article said so:

While some evidence of biological processes were seen, the damage the elements had on the cells are not enough for bringing the mammoth back to life.

Nonetheless, the comments showed the power of the headline. At the time I reviewed them, there were 754 in total. Thirty-three percent (33%) offered political statements based on the headline that either had little to do with the subject matter or evinced a complete lack of understanding of the topic and instead rehashed common tropes heard in certain media, including social media.

Forty-three percent (43%) made jokes primarily related to the headline, but not the content.

Only 6% had anything intelligent to say on the actual subject matter and points raised within the article itself. The rest of the comments were either spam or the ramblings of people (or bots) who simply wanted to insert some text somewhere on the internet.

Even outlets that tend to do a decent job of reporting the story rely on headlines that start the reader from a position that can influence their understanding of what they are about to read. See if you can spot the problem in this one:

The key here is in the sub-heading. What the main headline is effectively asserting is not necessarily what may have happened, but rather what the researchers claimed may have happened. Upon reading the article, however, it is apparent that experts in the field do not necessarily agree with the claim about “500 million years” of evolving.

AI-generated proteins are not new, and some have argued that the problems with applying them to real-world uses are not solved by this experiment. Thus, the “groundbreaking” nature of this research is potentially overhyped.

Digging a little deeper into the matter, I found that the authors of the research are also hoping to commercialize the AI they used for their result. It comes as no surprise that they would offer potentially bombastic claims about what they accomplished. Introducing the news piece with what they said rather than what their experiment did rings more like an endorsement than an objective report.

Here is another:

Once again, the headline is centered on what an entity with a vested interest had to say about a scientific story rather than what happened. In discussing the number of computations allegedly performed by the latest quantum chip, the founder of Google Quantum AI was quoted in the story with the following:

This mind-boggling number exceeds known timescales in physics and vastly exceeds the age of the universe. It lends credence to the notion that quantum computation occurs in many parallel universes, in line with the idea that we live in a multiverse.

Many have scoffed at this notion. Sabine Hossenfelder, a physicist YouTuber, explained the opposition quite clearly:

This is why… the Google press release uses this vague term “parallel universes” which no one really knows what it means, rather than the many-worlds interpretation, and why it says their experiment is “in line with” a multiverse rather than “proves the existence of a multiverse.” And then they blame everything on David Deutsch.

Because they fully know that just demonstrating that quantum computers work is not evidence for the many world’s interpretation. It’s evidence that quantum physics works as we think it does, which requires these superpositions.

[Deutsch is a physicist who has claimed that quantum computers support the viability of the many-worlds interpretation].

COVID also provoked a plentitude of yellow journalism:

One should immediately pause when a headline claims 100% efficacy in anything. If that wasn’t skepticism-inducing enough, the article’s opening all but gave away the pending sensationalism:

an attorney familiar with the details, claimed that a world-renowned French researcher had tested a promising cure for coronavirus.

So stipulated, your honor.

What is particularly revealing about this story is that it never discusses the details of the alleged study—no mention of the number of participants or the methodologies—nor does it link to the study itself. Few here will be surprised to learn that the “miracle” drug mentioned is not even recommended for treatment of COVID, let alone a cure.

From bad headlines to misbegotten beliefs

These kinds of headlines often suggest a level of technological or scientific development that either does not yet exist, may never exist, or cannot achieve the results that laypeople will think it can. It is this kind of distortion that gives rise to conspiracy theories and misapprehension of critical or foundational matters.

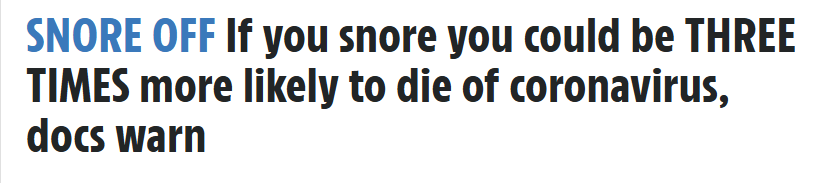

Others, like this one, ignore key pieces of information that make things sound more daunting than they are:

The conclusion of the study to which the article referred applied to people specifically diagnosed with sleep apnea who contract COVID, not people who snore for other reasons.

Articles crafted this way create fear in people where it is unwarranted. This also leads people to act on conspiracy theories or other dangerous beliefs that can cause real world harm.

This is a concise, well-written headline describing one consequence of sensationalism.

Writing good headlines is hard; writing deceptive ones is easy

Writing good headlines is tough, even if the writer is mostly unconcerned with traffic. After all, most people do not spend the time researching and putting together essays for their own edification. Whether the goal is to entertain or educate, there is at least some desire to see that people interested in the topic can find and read it. The headline functions as the signpost for this purpose.

But creating a really good one is far harder to accomplish than one who has never tried might appreciate. A headline that is too dry or technical may dissuade people who are only somewhat interested or have limited knowledge of the topic. One that fails to provide a strong indicator of the content may not capture the attention of readers who are selective about what they choose to explore further.

These problems all but go away when the motive is profit or attention. If the goal is simply to entice people to open a link, all that is needed is something that provokes emotion—good or bad, it makes no difference. It is why many blog writers have chosen to write exclusively on politics or social issues.

This genre makes it easy to craft outrageous headlines that will bring clicks. Most of the content is unsupportable nonsense, but that is of little import because the intended audience is comprised of those seeking to validate their emotionally driven views. They are not engaging to learn or debate ideas or grapple with evidence; they are merely seeking the reverberations of their chosen echo chambers.

Some publications seem intent on drawing from this same strategy even on science and education matters. You may recall my piece on black kitchenware. In that case, a mathematical error led researchers to dramatically overstate the conclusion. News outlets did not waste any time in running with it to stir their readers’ emotions (and get clicks) as a result.

Not a single one of these platforms appear to have read the study (other than the conclusion), so not a single one of them caught the (very simple) math error within it. (And yes, the reviewers should have detected the error prior to publication in the journal, something I discuss in my article linked below, but that does not exonerate the media).

Instead, the media focused on its sky is falling narrative. Only after YouTuber Adam Ragusea discovered a missing zero in the researchers’ calculations did the issue come to light. Nevertheless, The Los Angeles Times and others did not post follow up news stories with equally compelling headlines, such as:

Your cool black kitchenware is almost certainly not poisoning you. We just didn’t thoroughly analyze the study before reporting on it!

Readers have some responsibility in this, too

Avoiding clickbait and sensationalism is not solely the job of writers.

It seems that by now we should all be aware that using deceptive headlines to increase engagement is common, perhaps even overwhelming. Just as writers (or editors) have a moral obligation to craft worthy headlines so, too, do readers shoulder the responsibility not to rely on them as sources of information.

Not only do headlines provide little, if any, useful information themselves, but they often fail to accurately introduce readers to the associated content. Forming opinions or reposting stories on social media solely from reading a headline is an untoward activity akin to spreading playground rumors. One way to improve our rapidly withering social discourse is to stop doing this.

If a headline captures your attention, that’s great. That is what they are intended to do. But it is necessary to read the subsequent article before forming any opinion on the subject. Oftentimes, the reader will find that it says something notably different than what is initially proclaimed or implied.

For help with identifying and dissecting sensationalized or misleading science reporting, see USC Berkeley’s excellent primer here.

If you enjoyed this article, consider giving it a like. It helps placate the all-controlling algorithm. Or if you wish to give a nod to my work, I would be eternally grateful if you Buy me A Coffee.

* Articles post on Wednesdays and Saturdays *