Right Wing Populism Has Been A Disaster for U.S. Counties and States

Now it is gripping the nation

Populist far-right parties are not a homogeneous group, but they share several core ideological positions, such as nativism, populism, and authoritarianism.

Quality of life is dependent upon public support resources and institutional equality. When either of these erodes—either through poor policy choices or active intent—public health suffers, and leads to lower average life expectancy. As the general well-being of a populace declines, populist candidates tend to make gains at the ballot box.

The mantra of right wing populist candidates is to offer simple solutions to complex problems, often identifying one or more scapegoats as the source of society’s woes. If elected, they usually satisfy at least some of the promises they made to acquire power by executing policies that ultimately make the problems worse.

In the United States—where life expectancy, poverty, and public welfare are worsening, or already at their worst in decades—populists have held ground or made substantial gains at both the federal and state levels. This was especially true in the 2024 election.

[P]opulism [is] a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups: “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite,” and argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.

— Dutch political scientist Cas Mudde

Right Wing Populism defined

Current extremist populists in America exhibit distinct parallels to their counterparts of Europe in the 1980s. They primarily target immigrants and national minorities.¹ Under this rubric, immigrants and minorities function as the tools of ‘corrupt elites.’ This belief is illustrated in commentary like this one from Peter Kirsanow at the National Review:

Millions of illegal aliens have flooded the country during the Biden presidency. An indeterminate number — estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands — have been flown into the country by the Biden administration and deposited in certain jurisdictions.

Increasingly, Democrats needn’t be concerned about persuading American voters. They’ve gained electoral votes by the addition — strategic or otherwise — of illegal immigrants. [Emphasis added]

Although views like this are not new — immigration has been a political foil for nearly all of American history and especially following demographic changes that started in the 1960s — Donald Trump may be the first politician to acquire the American presidency almost entirely on a populist wave of xenophobic and racist furor since Andrew Jackson.

Nevertheless, the politics of exclusion, division, and otherizing in the modern context pre-date Trump’s political career by decades. This history enables analyses of their effect on the populations that have adopted the rhetoric into their leadership structures. The results are consistently bad for the public both economically and in terms of public health and well-being.

Right wing populism is an ideology built on unsubstantiated fears. This authentic image, featuring Donald Trump from an old clip most platforms have scrubbed from the internet, is devilishly apropos. Source: Meidas Touch

According to populists, no issue is complicated, there are only simple and immediate solutions. Their fundamental Manichaen worldview leads them to select scapegoats… Their idea of the nation is based on ethnicity and identity, thereby rejecting foreigners and immigrants.

— Marc Lazar, Senior Fellow — Italy, Democracy and Populism

American Populism

The two primary indicators of government failures that influence elections are economic prosperity and life expectancy (which is directly linked to or inextricable from public welfare policy).

Voters who are mired in the miseries of economic, public, or health service deficiencies can be easily persuaded that the best choice in an election is the candidate who ostensibly seeks to “burn down” the system and take vengeance on enemies.

Scholars and commentators may debate what “kind” of populist an individual politician is, but as Sidney Milkis and Nicholas Jacobs wrote, “we see a common refrain.” Populists “have routinely exploited the pervasive belief that the country’s political system is rigged and illegitimate.” The enemies targeted by populists include anyone they can associate with facets of these alleged illegitimacies.

Because realistic and effective solutions tend to be complex and opaque to many voters, successful candidates necessarily weave narratives of simplicity that are highly amenable to the unsophisticated. This is evident in the Trump administration’s messaging about tariffs:

The extraordinary threat posed by illegal aliens and drugs, including deadly fentanyl, constitutes a national emergency… Until the crisis is alleviated, President Donald J. Trump is implementing a 25% additional tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico.

The underlying message appears to be that the United States will use tariffs as a form of punishment until the Canadian and Mexican governments do… something… to “[halt] illegal immigration and [stop] poisonous fentanyl and other drugs from flowing into our country.”

On its face, it sounds reasonable to some. But of course, if those governments had some magic wand that could solve such difficult problems, they would have done so already. Moreover, this rhetorical tactic operates under the presumption that the United States holds no blame — or role — in the problems or their solutions.

Unfortunately, in the United States, voters have re-elected populist politicians or chosen their ideological successors who have repeatedly posited failed policies over decades. For example, in areas of low or decreasing life expectancy, poor public health services, and economic depression in the United States, voters selected populist Republicans more often in the 2016, 2020 and 2024 elections, irrespective of prior voting patterns.

[Former Alabama Governor George] Wallace’s base was among voters who saw themselves as middle class — the American equivalent of “the people” — and who believed themselves to be locked in conflict with those below and above.

Modern Republicans are the progeny of right wing populism

Sociologist Donald Warren credited former governor of Alabama, George Wallace, with creating “a new rightwing variety of populism” in a seminal work published in 1976.² Wallace’s politics were founded upon racism and segregation. But he also incited anger against many entities that voters today will find strikingly familiar:

[Wallace stoked] his campaign fires with popular rage and resentment against hippie radicals, Black Power activists, and urban rioters… he blamed their elite enablers: newspaper editors, television producers, college professors, government bureaucrats.

Other Southern politicians ran on similar platforms, such as John Bell Williams, governor of Mississippi from 1968 to 1972, and Orval Faubus, governor of Arkansas from 1955 to 1967. Faubus once proclaimed, “No school district will be forced to mix the races as long as I am governor of Arkansas.”

Giovanna Campani et. al. note that evolving views on racial equality and increasing numbers of immigrants to the US shifted political targeting toward the latter group.

Regardless, the two are not mutually exclusive, and present-day populists have not eschewed a racially charged message. Arguments invoking immigration and racism are often intermingled and proffered in a way to sound sufficiently refined, while still maintaining the necessary provinciality to appeal to those predisposed to ‘othering’ political rhetoric. They are, in effect, pseudo-intellectual bigotry masked as criticisms of institutional problems.

Furthermore, they do not elide other equally vapid complaints. So-called paleoconservatives long clamored against the “global liberal ideology,” which purportedly targets ‘‘traditional social orders, states, ideas, and identities that oppose its expansion.” Today’s populists have carried on the fight to preserve fabricated versions of these traditions, employing rhetoric similar to that of their predecessors.

Sam Francis, a journalist with the Washington Times and advisor to failed presidential candidate Pat Buchanan, explained in 1996 the plight of what he called “Middle Americans.” This helped to form the framework for positioning paleoconservatism into current populist messaging:

They find that their jobs are insecure, their savings stripped of value, their neighborhoods and schools and homes unsafe, their elected leaders indifferent and often crooked, their moral beliefs and religious professions and social codes under perpetual attack even from their own government, their children taught to despise what they believe, their very identity and heritage as a people threatened, and their future — political, economic, cultural, racial, national, and personal — uncertain. They find that no matter which party or candidate they support, no matter what the candidates and parties promise, nothing substantially changes, except for the worse.

From this emerged the “America First” concept. It is an openly nationalist platform that situates itself as the “foundation of our cultural and social identity.” It is not merely an effort “to revert to an idealised account of 19th-century nationalism.” What it postulates is an arguably more nefarious purpose:

What the radical right wants more than anything is to take control of globalisation to build an alternative order in which free-market capitalism thrives but which is firmly anchored in notions of shared civilizational heritage, myths of inherited communities and their traditional sources of authority, and in which the West is redefined accordingly against the cultural and demographic threats from Global Islam and the Global South.

It is the quintessential “us versus them” ideology that depends on imagined culture and history, along with presumed superiority. Through traditional applications of force, it condones the subjugation of those that fall outside of the accepted paradigm — those who are non-white, non-Christian, or some form of ‘other’ — to extract from them any benefits to sustain the material, moral, and political authority of “true Americans.”

Contrary to the claims made by many pro-populists today, this is an experiment that has been tried and failed. An analysis of the results in places governed under this ideology unequivocally show that the public has suffered under the principal metrics that drive the very votes that put populists in power in the first place.

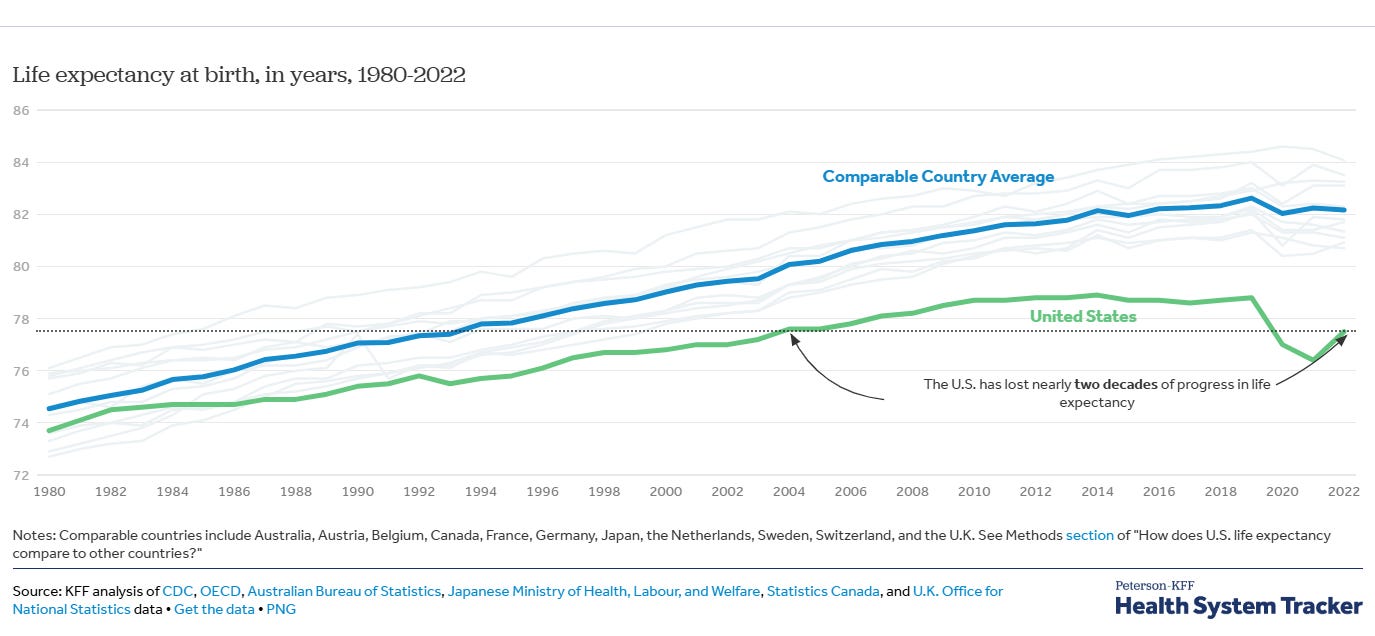

Source: Healthy System Tracker

Life expectancy under localized populism

Among the wealthy countries of the world, people in the United States live the shortest despite spending extraordinarily more on healthcare. This does not tell the whole story, however. At the granular level, the disparity within the country is significant and correlates directly with the political affiliation of localized leadership.

Life expectancy among American males ages 25 to 64 began declining in the 1990s within certain causal categories. By 2010, mortality rates worsened across all causal categories. This led to a decreased general life expectancy across all demographics starting in 2014.

At the state level, life expectancy remains highest in Democrat-led states, with only Republican-led Utah ranking in the top-ten. The states with the lowest life expectancies are Mississippi (74.6), West Virginia (74.9), Alabama (74.9), Kentucky (75.1), Arkansas (75.4), Oklahoma (75.5), Louisiana (75.5), Tennessee (76.1), South Carolina (76.2), and Ohio (76.6).

All ten are historically Republican-majority states, and nine of the ten (in bold) also contain the largest proportion living below the poverty line.

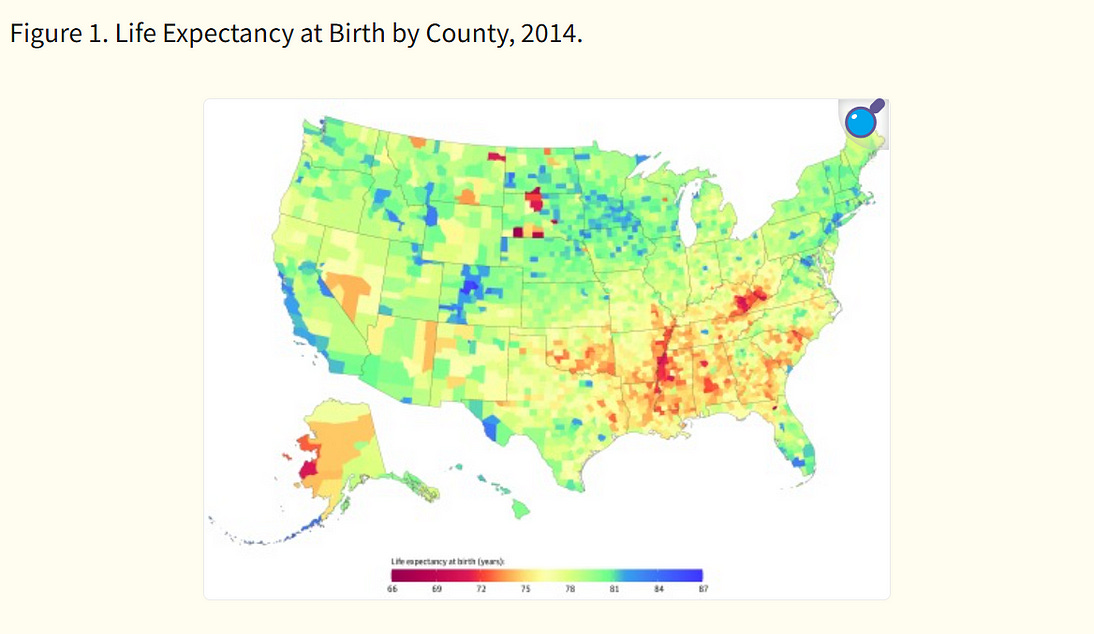

In 2017, researchers showed that life expectancy varies even more widely among counties. There was a 20.1-year gap between the best and worst. As the image below indicates, life expectancy is the lowest primarily in the southeastern United States.

Life expectancy rates are worst in the red and improve up to blue. Sourced from Dwyer-Lindgren, et. al.

These researchers determined that “socioeconomic and race/ethnicity factors alone explained 60%” of the differences among counties. Behavioral traits brought that number to 84%, though these factors are often directly related:

[R]esearchers now recognize that the relationship between socioeconomic status and health likely reflects causal pathways running in both directions (ie, from better health to higher socioeconomic status as well as from higher socioeconomic status to better health).

Worsening economic conditions lead to poorer health outcomes and lower life expectancies and vice-versa. Such conditions already trend lower for racial and ethnic minorities, exacerbated by demonizing political rhetoric because it contributes to negative behavioral elements. Combined, all of this affects people’s perceived well-being. When well-being scores decline, votes for populists tend to go up and the cycle continues.

Red economies

Economic indicators trend unfavorably in Republican controlled political units. For example, the states with the highest poverty, listed here in order starting from the worst, are almost all led by Republicans:

Mississippi; Louisiana; New Mexico; West Virginia; Kentucky; Arkansas; Alabama; Oklahoma; Tennessee; South Carolina.

Only New Mexico and South Carolina have notable ideological diversity in their state level leadership.

States indicated by party strength; dark red indicates heavily Republican and dark blue heavily Democrat. Source: A Red Cherry , CC BY 4.0.

New Mexico’s poverty level is somewhat of a statistical outlier because 49.3% of its population is of Hispanic ancestry — the highest in the US — and it has the second largest population by percentage of Native Americans. Both of these groups have faced historic discrimination in education and the labor market. They are also routine targets of right wing populist politicians and pundits.

Despite being the poorest states in the Union, only two of those listed above spend within the top-ten per capita on public welfare programs — Kentucky and New Mexico — as these programs have come to be associated with the opposing political ideology. In 2024, fourteen Republican-led states even turned down federal aid offered to help the impoverished.

These fourteen states included some of the poorest: Louisiana, Alabama, South Carolina, and Mississippi, specifically. Some of them rejected the aid on overt ideological grounds. For example, Republican Gov. Tate Reeves of Mississippi, in a speech explaining the choice to decline the aid, stated:

[If Democrats had their way] Americans would still be locked down, subjected to COVID vaccine and mask mandates, and welfare rolls would’ve exploded.

The numbers indicate that Republican social and economic policies have failed their constituents particularly severely in the last decade or so. In 2019, the Brookings Institute released a report that concluded:

[T]he two parties have in just 10 years gone from near-parity on prosperity and income measures to stark, fast-moving divergence.

Some of the key indices it identified included:

Democratic districts median household income rose from $54,000 in 2008 to $61,000 in 2018; Republican households began slightly higher in 2008, but then declined from $55,000 to $53,000.

Overall, “blue” territories have seen their productivity climb from $118,000 per worker in 2008 to $139,000 in 2018; Republican-district productivity remains stuck at about $110,000.

Since 2008, Democratic districts’ share of professional and digital services employment surged from 63.7% to 71.1%; GOP districts’ professional and digital employment fell from 36.3% to 28.9%.

Democratic-voting districts have seen their share of adults with at least a bachelor’s degree rise from 28.4% in 2008 to 35.5%; Republican districts have barely increased their bachelor’s degree attainment beyond 26.6%.

Correlation versus causation

The correlation of poverty and decreasing life expectancy to Republican control is apparent in the facts and figures above. But correlation does not necessarily prove causation. Nevertheless, in many of these states, the longevity of high poverty rates that remained under right wing populist control strongly suggests that it heavily factors in causation.

For example, in 1959, Mississippi, Arkansas, and South Carolina comprised the most impoverished states. They rank first, fifth, and ninth today. By 1979, while some southern states saw economic upticks built on energy development, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, and Louisiana remained among the poorest. Today, these five states are all still among the top-ten poorest in the nation.

Juvenile politics are a top-down malady in the United States right now. Source: clipped from Fox News

Their leadership has continued to embrace populism with fervor. Arkansas governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders, for example, frequently makes comments like this:

Most Americans simply want to live their lives in freedom and peace, but we are under attack in a left-wing culture war we didn’t start and never wanted to fight.

Louisiana governor Jeff Landry said in a statement:

A vein of populist conservatism has been running through the country for the past decade now. That really suits the politics of Louisiana as well.

Some of them have embraced populism in more juvenile form, following in the President’s footsteps. The governor of Mississippi, Tate Reeves, for example, embarked on a back-and-forth with other state Republicans over a legislative dispute. Tate wrote on social media:

Happy Gulf of America Day… Plastic straws are back, baby … And the sharks munching through the ocean are gonna be just fine!

The Mississippi Sun Herald called it “a chat between some petulant third graders,” that occurred “because Mississippi Republicans have such control of state government, they don’t have any powerful Democrats to harangue.”

Juvenile or even immoral behavior has become the rule, not the exception, among populist Republican leaders. This despite their claim to comprising the “moral majority.” It seems to have overtaken any concern for enacting intelligent policy.

The best of bad choices

There is no question that other factors contribute to poverty and, therefore, lower life expectancy. But the notion that the simplistic, populist politics of Donald Trump or the Republican party will provide effective solutions is simply unsupported by the numbers. Even a surface level review of their recent proposals indicates their patent absurdity.

Many who vote in that direction will point to the myriad deficiencies of the Democrat party as justification. Their discontent is not unwarranted. After the Reagan administration, which began the most rigorous assault against the middle class in nearly a century, both parties have since cozied up ever more closely to the rich, leaving everyone else adrift.

The United States is now ranked fifth worst in economic inequality of all G20 nations, better only than South Africa, Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina. Nevertheless, a meta-view of legislation in the decades from the Reagan administration to now shows that the public benefitted more often under Democrat-led majorities than Republican.

Gross inequality. (Higher number means higher inequality). Source: Statista

Flawed as it clearly is, the United States government is simply too big to dismantle all at once. Trump’s efforts to eviscerate it from within the executive branch is sure to end in disaster, regardless of whether it has popular appeal. Unfortunately, Congress has shown no backbone to thwart the ongoing, decades-long corporate coup or Trump’s childish agenda. And the Supreme Court is at best, ideologically favorable toward elitism, and at worst, corrupt.

Over the next four years, the American people are likely to become more disenfranchised than ever, which may open the door to an authoritarian populist who is even more dangerous than Trump, and wise enough to surround himself with others who are as well. Given its integration into the affairs of the world community, a collapse of the United States political system will be catastrophic for everyone, not just Americans.

Notes

1 — Berezin, Mabel. 2013. “The Normalization of the Right in Post-Security Europe”, in: Armin Schaefer and Wolfgang Streeck (eds.), Schaefer, Armin and Wolfgang Streeck. eds. Politics in an Age of Austerity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

2 — David I. Warren. 1976. The Radical Center: Middle Americans and the Politics of Alienation. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

If you found this essay informative, consider giving it a like or Buying me A Coffee if you wish to show your support. Thanks.