A Simple Math Error Revealed the Problem with Access to Knowledge

The black plastics case study

Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash

A recent story to briefly explode in the news advised people to start emptying their kitchens of black plastic utensils. The reporting warned of imminent danger, which justified the instructions to take drastic steps. It turned out to be another round of fearmongering driven by a simple mathematic mistake—one discovered by a cook on YouTube. That YouTuber’s discovery only happened because in this case, the study behind the panic was open-access. Unfortunately, far too many are not.

The access paradigm

Academic scholarship is published in various journals, most of which require a paid subscription to access. Many universities and colleges have institutional accounts, which grant rights to their staff and students. For the rest of the public, there are limited options available if one wants to read a specific article:

Purchase the individual article (expensive);

Try to find it posted online somewhere (limited success);

Reach out to the author for a copy (limited success and time consuming);

Read third-party reporting on the study, but not the original work (many problems with this).

None of these solutions are ideal because they effectively restrict the audience that can analyze conclusions. Moreover, they limit the creativity of potential critiques because most people simply will not put forth the effort necessary to acquire more than a few—if any—scientific articles if those folks are not directly involved in the relevant discipline.

While many academic articles are dense and not easily consumed by a curious public, this is not a good justification for locking them behind paywalls that only scholars can bypass (through their institutional accounts). A recent occurrence proved it. This study made a claim that led to an abundance of fright-inducing reporting:

The problem? It had a major mathematical mistake that led to a vast overstatement in its conclusion.

The reason why this incident provides profound support for making all academic scholarship open-access is because the study passed peer review and was published. It was not a mathematician or scientist who discovered the mistake. It was a YouTuber.

Scary black kitchenware

The apocalyptic reporting in the graphic above arose from conclusions reached in a scientific paper titled, “From e-waste to living space: Flame retardants contaminating household items add to concern about plastic recycling,” published in the journal Chemosphere, Vol. 365, Oct. 2024. The authors made the article open-access, which will be explained further below. It is available in full, here.

The authors described their research as follows:

This study explored the presence of FRs [flame retardants] in plastic household items on the U.S. market, particularly in items with high exposure potential, hypothesizing that some black plastic products on the U.S. market would be contaminated with emerging, phased-out, and commonly-used FRs and that products containing electronics-associated polymers would have higher levels of contamination.

From their testing, they made the following conclusion:

These results show that when toxic additives are used in plastic, they can significantly contaminate products, made with recycled content, that do not require flame retardancy. Products found in this study to contain hazardous flame retardants included items with high exposure potential, including food-contact items as well as toys.

Within weeks of the release of the paper, media began picking up and running the story that black kitchen utensils are dangerously toxic and people should “throw them away.” A highly-read essay posted by the Food Network, for example, recommended throwing away these kinds of utensils and replacing them with stainless steel or glass ones. It added:

If you choose to get rid of the black plastic items you have in your kitchen, you should throw them in the trash instead of the recycling bin. Yes, they’ll end up in a landfill which presents its own sustainability issues. But it’s better than letting them re-enter the plastic recycling chain to further contaminate other black plastics.

What added to the credibility of the Food Network piece was that its author, Christine Byrne, included the credentials Master of Public Health (MPH) and Registered Dietician (RD) to her name. Unfortunately, she—like many others—did not detect a key flaw in the study.

Black spatulas for sale on Amazon.

Flame retardants (FRs) contain toxic chemicals that, if consumed by humans at significant enough rates, can cause cancer or other maladies. Food utensils create an acute vector of transfer because they touch food that is consumed immediately thereafter. They are typically warm or hot at the time of contact, which increases the transfer capability among certain chemicals used in FRs. This is the “exposure potential.”

The authors of the study determined that the black kitchenware contains “high” exposure potential based on the “estimated daily intake” of FRs through contaminated products. They calculated this daily intake amount from black plastics to average 34,700 ng/day (an ng or, nanogram, equals 10−9 grams). US public health authorities have determined the maximum overall safe intake value to be 42,000 ng/day for a 60 kg (132 pound) adult, according to the authors.

People already suffer exposure to FRs through various sources, though the intake rate is typically extremely low per source. These include dust, food with FR exposure from packaging or manufacturing, and household products like furniture. Dust ingestion, which is generally the most prolific source, leads to an average of 250 ng/day for most people.

Using black kitchenware, according to this study, contributes to at least 80% of the allowable safe consumption of FRs. This is problematic because the percentage will be much higher for smaller people, particularly children. (Safe allowable intake is based on the parts per gram of latent FR chemicals as a percentage of overall body mass). Furthermore, because the intake value represents an average, some people who use black kitchenware will ingest greater volumes of FRs, potentially putting them over the daily limit.

Where the authors of the study went wrong is in calculating the safe allowable daily intake of FRs. They determined the number from the official reference dose formula of 7000 ng/kg bw/day. YouTuber Adam Ragusea saw this and posted a video titled “The worry about black food plastics,” just a week or so after the flurry of dark reports came out. He said:

I don't know if I want to say this, but there seems to just be a basic arithmetic error in here, and I'm totally open to the possibility that I'm the idiot and I'm seeing it wrong. [12:00]

Mr. Ragusea was not wrong. The study authors, who asserted that the maximum safe intake per day is 42,000 ng/day for a 60kg person, were off by a factor of 10.

7,000 ng x 60 kg = 420,000 (not 42,000).

If the remainder of their data and calculations are correct, exposure caused by black kitchen utensils raises the daily rate to only 8% of the safe allowable maximum, a far less perilous situation.

To be clear, mistakes happen. Detailed studies contain numerous calculations and scientists are human. It is for this very reason that scientific journals adopt the peer review process, to put more eyes on any area where potential mistakes can occur. This study was not an exception—it underwent peer review. So what happened?

Photo by Raghav Modi on Unsplash

The problem with peer-review

Put simply, the peer reviewers missed the error. They apparently focused so intently on the methodologies involving the exposure vectors and consumption rates, that none bothered to confirm the actual safe allowable limit.

Those who work in academia or have experience with publishing in academic journals are quite familiar with the peer review process, and its growing failures. Academic journals and book presses rely on a system of volunteer reviewers. Publishers seek specialists in the requisite field to read and analyze proposals for errors just like the one found in the study at issue in this essay. A key problem is that reviewers are not paid for this work, and it is burdensome.

I have acted as a reviewer myself. The process can take hundreds of hours, depending upon the nature of the reviewed work. Whether of the sciences or humanities, reviewers must fact-check first, which might involve conducting high level math or extensive tertiary reading. Reviewing also requires confirming footnotes and sourcing. In my case, this included works in multiple languages, some of them as dense as the proposed study. Then, the conclusions of the paper itself must be analyzed. This may demand parsing more math, statistics, scientific processes, etc.

As humans are wont to do, keen attention is often given to the bolder claims with less rigor applied to simpler or more widely understood matters. Because reviewers all have specific areas of expertise and different histories and experience, engaging several of them helps to ensure that all claims—even the provincial ones—in a proposal are carefully examined. Unfortunately, this is becoming very difficult.

Researchers and scholars live busy lives. Some teach, some perform time-sensitive research, and still others have administrative obligations or other responsibilities associated with their position. Academia often involves imminent deadlines. During the pandemic, many endured lockdowns leading to a brief uptick in the availability of reviewers. Since then, however, the situation has worsened beyond pre-pandemic levels.

A key problem is that the process requires people to willfully contribute great amounts of time and effort without pay. While many academics share my view that disseminating information is more important than making a buck, we still suffer from the vicissitudes of our capitalist system. In other words, if someone is paying us to do something, we have to give that priority over volunteer activities.

Older, more experienced researchers who have accumulated greater levels of expertise are increasingly either refusing to participate or only offering their services for compensation. They argue that for-profit publishers make huge sums of money and should share some of that with the people who are critical to the process.

Roland Hatzenpichler, assistant professor of environmental microbiology at Montana State University, for example stated:

I’m not saying I have the solution to the problem, I’m just saying that I cannot offer my services to a company that gives nothing back to the community.

Publishers tend to ignore experts who have resisted offering their services for free despite the fact that many of these companies make millions—or even billions—in profit. Instead, these companies seek out those who are willing to take on the role for no pay because they are newer to their respective field and hope to gain favor to bolster their own chances of getting published later. This is resulting in peer reviews being conducted by less experienced, overburdened scholars much of the time. And it is difficult to recruit even them.

James Heathers, a scientist who writes on Medium, articulated the issue well:

Journals, as privately owned or publicly traded companies, have made it even clearer. They publish P&L statements. They have investors, and boards of directors, and they calculate revenue growth, and operating income. Part of their revenue growth and operating income is made out of your research…

They want to publish research within a closed environment, not building community resources, not making processes transparent, not sufficiently weeding out bad research, etc.

In Heathers’ view, publishers don’t prioritize the dissemination of accurate information—the core reason for their existence—because they are worried more about satisfying investors. Such is the 21st century concisely described. And he is not the only one who has identified this problem. The evidence clearly shows that this model is a failing endeavor.

The solution to this, as perfectly exemplified in the black kitchenware incident, is to make all academic publishing open-access.

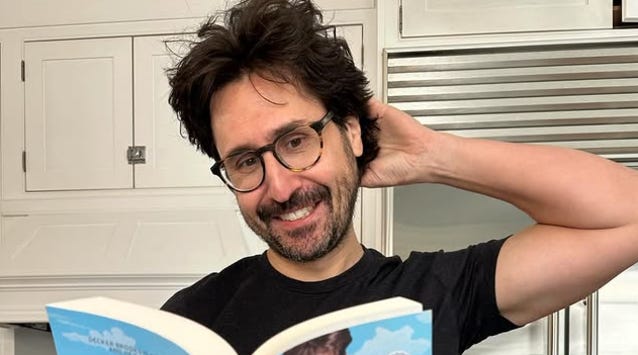

A screenshot of Adam Ragusea from his Instagram.

What is open-access?

Adam Ragusea appears to have been the first person to identify the mistake in the black kitchenware paper. He is not a scientist. Instead, I will allow him to describe himself:

I cook on the internet, mostly YouTube. I post a recipe video on Thursdays and some other kind of video about food on Mondays. In between, I put stuff on Instagram. I’ve been doing this since a pizza-making video I did randomly went viral in March, 2019. I taught journalism at Mercer University 2014-2019. Before that, I was a public radio reporter. Before that, I was (trying to be) a composer. I still sometimes do journalism, write music, make podcasts and teach.

Ragusea located the mathematical miscalculation because of one key fact: the article was available to the public (thus, open-access). Open-access simply means that a publication offers the full text and content of a published article for free. Any person, irrespective of whether they are an account-holder, can search for, find, and read a given piece in a journal. There are two basic ways an article becomes open-access.

The first is that it is published in an open-access journal. According to the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), there are 13,639 academic journals that do not charge fees for access to their content. This sounds pretty good, but it is important to note that many of these are highly specific. Some examples include: Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science; Music & Politics; Scientific Journal of the Military University of Land Forces; and Journal of Copyright in Education and Librarianship, to name a few.

Moreover, many of the journals included in that thirteen thousand figure are in languages other than English, some of them rather obscure. For instance, there are 24 open-access journals published in Basque. Globally, about 800,000 people speak the language—0.01% of the world’s population.

The most well-known and widely read journals—such as Nature, Science, and The Lancet—are typically not open-access. These names offer some open-access articles, but most of the content is locked down. Publishing in these journals does not come with a cost to the author (in most cases), but accessing the article is restricted to account-holders or those willing to pay exorbitant fees to purchase it.

The alternative to fully open-access journals is the publication of individual open-access articles.

Scholars who wish to make their articles accessible to the public can choose to publish in open-access or subscription-based journals. In either case, they pay an Article Processing Charge (APC) (with rare exceptions). MDPI, a publisher of many journals, explains the process this way:

Authors pay a one-time Article Processing Charge (APC) to cover the costs of peer review administration and management, professional production of articles in PDF and other formats, and dissemination of published papers in various venues, in addition to other publishing functions.

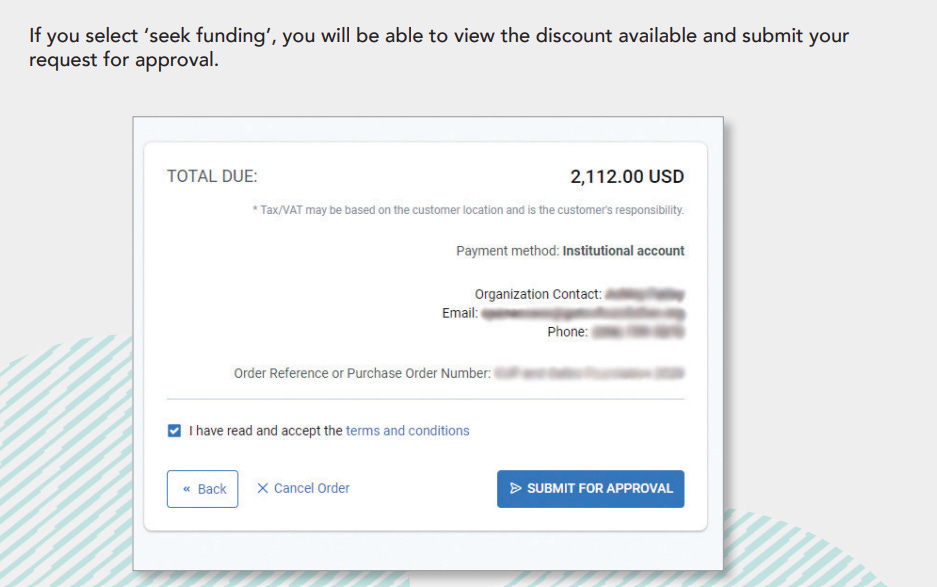

The cost of the APC can vary, but an example given by Cambridge University Press showed an image suggesting it is at or around $2,000 USD. For new scholars who often make low incomes, this is an absurdly high amount. Cambridge University Press reported $1.29 billion in revenue in 2023-2024.

MDPI’s description is rather ridiculous on its face. Most of the “publishing functions” it describes cannot conceivably cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars per article. We already know that publishers do not pay peer reviewers and, based on my own experience, the ‘management’ of them consists of exchanging emails every few weeks to months.

Likewise, the cost of producing a ‘professional’ PDF cannot be very high. Authors generally provide graphs and images themselves, which leaves the publisher to do some basic formatting. And this is likely done with preestablished templates. As for the ‘various venues’ of distribution, in most cases this is a website.

Sourced from “An Author Guide to Paying an Article Processing Charge (APC).”

There are some benefits to open-access publishing in the current paradigm. Those who choose this option typically retain at least some rights to their work, which allows the author to publish or use it elsewhere (depending upon a number of circumstances). It also increases the chance of getting the article published in the first place because open-access journals tend to have more favorable ratios of submission-to-acceptance.

Why all academic journals should be open-access

In my view, there is no prohibitive cost to turning all academic journals into open-access. That it would destroy the market where investors enjoy their current windfall is not a compelling counter. After all, without having to pay a bunch of shareholders, it would take only very modest revenue streams to support publishing enterprises, even ones that include paid reviewers. Many have offered ideas toward this end, so I won’t rehash them here.

Current arguments against publishing in open-access journals revolve around the potential for fraud or predatory publishers. If the profit motivation is removed, however, then most of these problems will go away. Furthermore, if journals paid peer reviewers, it would strengthen that process and abrogate potential abuse even more.

A critical reason why this shift is necessary is exemplified in the black kitchenware incident, but there are many others. For one thing, it would make it harder for people with nefarious agendas to misrepresent the conclusions or contents of studies because more people would have the ability to conduct their own analyses. This would strengthen public dialogue about topics, especially those with political importance.

As the black kitchenware case showed, there are plenty of intelligent people who do not work in the relevant discipline, but care deeply about what scientists and researchers conclude about certain topics. Broader access to studies enables such people to examine research related to their areas of interest rather than rely on reporting that does not necessarily involve careful scrutiny. This can help identify errors or to create a more informed field of people who depend upon scientific findings for various reasons.

Allowing the public to access all academic content might have the ancillary effect of improving the writing and presentation of papers. While some fields unquestionably require jargon to make complex findings clear to other experts, not all fields or studies demand this kind of language.

Certainly, some scholars will write to a broader audience if they know many more people could potentially read their work. Indeed, of the relatively few scientists who have become famous, most of them are exceptional writers. This could be motivating to others.

Stop monetizing everything—especially critical functions

A global paradigm shift is coming, whether the investor class likes it or not. It may not happen in my lifetime or yours, but the question is not one of if. Rather, it seems to be a matter of whether it happens because as a species we begin an evolutionary process into something more sustainable and sensible; or we suffer a cataclysmically forced change.

Demarking the success of everything, no matter its necessity to the human condition, by the amount of profit it can generate is a fool’s quest. Just as healthcare, climate preservation, or our general wellbeing as a species should not be commodifiable, neither should we put a price on access to information derived from the scientific process.

Doing so creates a division that leads to destruction. It splits society into critical thinkers and gullible super skeptics. Although not the sole reason, it greatly contributes to why charlatans have found our interconnected age so lucrative. They profit handsomely off the latter. Because so many people get their information from social and legacy media, if access to information is limited, it allows the crowd who fabricates it to dominate the discussion.

Changing the publication of scientific knowledge into a fully accessible system would definitely not solve the world’s problems. But it would be a good start toward putting a dent in the massive propagandic machine that is effectively destroying politics, human psychology, and society at large.

See you Wednesday.

* Articles post on Wednesdays and Saturdays - please consider sharing *

I am the executive director of the EALS Global Foundation. You can find me at the Evidence Files Medium page for essays on law, politics, and history; follow the Evidence Files Facebook for regular updates, or Buy me A Coffee if you wish to support my work.

And. Black plastics are separated from others early in most recycling processes. Black pigments can make it difficult for NIR sensors to discern, for example, polypropylene from polyethylene, which makes for a lower quality pellet mix in the end. Or at worst, makes it so low quality that it becomes incinerator fuel.