The US Is Failing in the Face of the Next Pandemic

Millions of birds are dying. And it looks like it will get worse, much worse.

Photo by Manuel on Unsplash

This article is dedicated to Tom and Billy who wanted to know more about avian flu.

In January of 2022, US health officials detected the presence of avian influenza among wild aquatic birds, commercial poultry, and backyard or hobbyist flocks. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported the spread of the disease to cattle in Texas in March of 2024. Many non-avian wildlife have also been identified as victims, including 18,000 dead baby elephant seals in Argentina. Additionally, sixty-seven human cases have been reported, resulting in one death.

While the human health effect remains low, the impact of the contagion on the lives of animals and the food economy has been extraordinary. More than 17 million chickens and perhaps as many as 52 million birds of various species have died since the initial outbreak, just in the United States. Other animals have died as well, but the number remains unclear. Experts estimate that, so far, the outbreak has cost between $2.5 and $3 billion.

Reminiscent of the early stages of the COVID pandemic, public authorities have not engaged in an exemplary response with clear messaging. Agencies have squabbled over what responsibilities belong to whom. State officials have often been left with limited or no information from their federal counterparts. And many have asserted that the federal government is conflicted between its mission of protecting public health and its business of “promoting and protecting America’s $174.2 billion agriculture trade.” Worse, funding for scientific research is sitting on a knife’s edge.

So what is avian flu, how does it affect animals and farmers, and what could happen next?

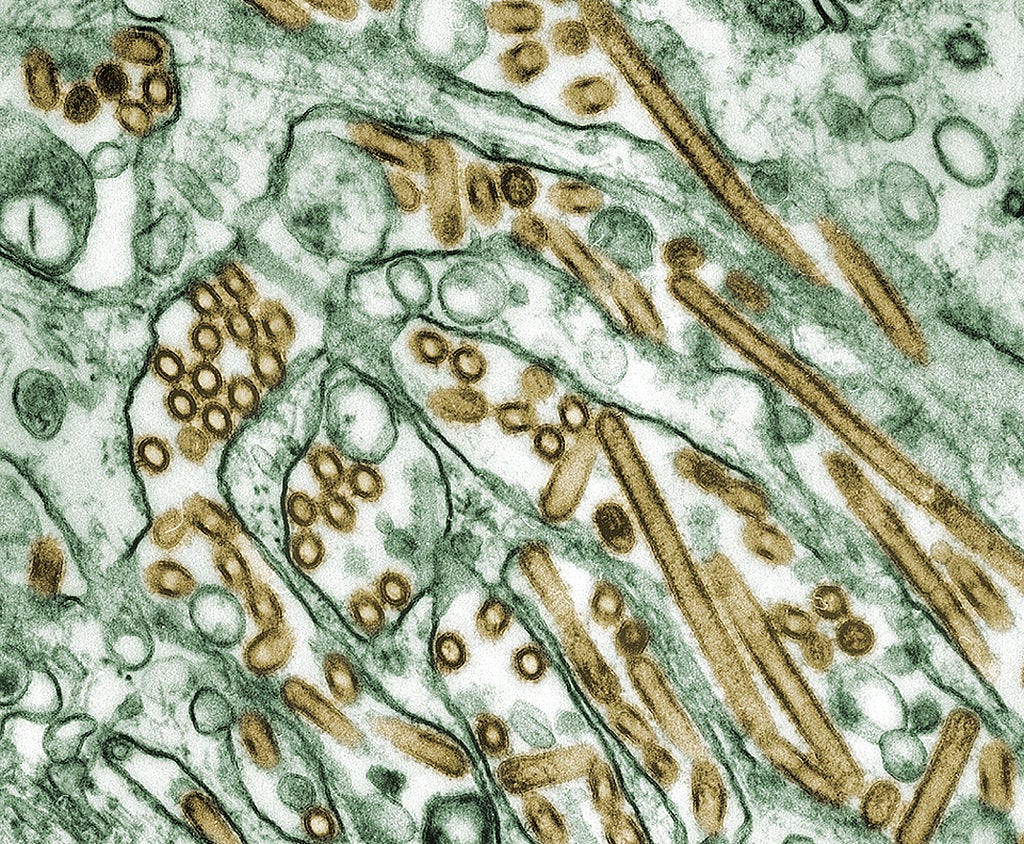

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (seen in gold) grown in MDCK cells (seen in green). Photo Credit: Cynthia Goldsmith / CDC

What is avian influenza?

Avian influenza is a virus of the family Orthomyxoviridae, in the genus Alphainfluenzavirus (influenza A). Of the seven influenza genera, influenza A affects birds. In the news, articles about Bird Flu — as the illness is often called — are sometimes accompanied with character sequences, such as H5N1.

The ‘H’ and ’N’ refer to the spikes that cover the surface of the associated virus; haemagglutinin (H) and the neuraminidase (N), respectively. There are 17 different types of haemagglutinin in A viruses (H1 to H17), and nine different types of neuraminidase (N1 to N9). Different combinations of H and N spikes present in influenza A viruses are part of what separates them into strains.

A viral strain is a variation of the genetic blueprint that distinguishes one genetically distinct lineage from another through one or more mutations. A viral variant is similar, but the mutation(s) is not sufficient to declare the new version as a separate entity (or strain).

H5N1 is the strain currently ravaging bird populations across the USA, specifically the 2.3.4.4b clade. (We needn’t go into granular detail regarding clades, but if you’re interested in what they are, see here.) Certain H5 and H7 strains are considered high-pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI), meaning they spread prolifically, typically through ingestion or inhalation. Notably, aside from H5 and H7, avian influenza viruses are generally low-pathogenic and, therefore, do not cause widespread death or damage.

Transmission of H5N1 can occur among flocks via “movement of infected poultry or contaminated feces and respiratory secretions on fomites such as equipment or clothing.” In other words, both infected wild birds and humans stained with the virus on their clothes or equipment can spread it, even to isolated domestic birds.

H5 and H7 infections often affect multiple internal organs causing a mortality rate of as much as 90% to 100% in chickens. Many do not display symptoms prior to death, which typically occur within 48 hours of infection. This makes it challenging to identify sick birds before they infect large populations, especially among those held in congested conditions, such as on a commercial farm.

Commercial chicken farm. Photo by Animal Equality International, via The Human League.org.

Protect the flock

** A “flock” here refers to any type of bird people collect in numbers greater than one, as any avian species is potentially susceptible to infection from bird flu.

For most small-flock owners, surveillance methods are simply ineffective forms of protection. There is no practical way to test for pathogens to isolate infected birds prior to transmission, and identification by visual observation will almost always be too late. The only viable solution for small-flock owners is to practice biosecurity.

The USDA has a guide available online to help. Among its guidance, the chief method for protection is preventing cross-contamination. Avoid carrying the virus between or among separated groups by keeping tools and clothing clean. Using disposable boot and clothing covers is a highly effective method akin to wearing fresh rubber gloves for individual tasks in a kitchen or hospital.

When feeding, use a neutral implement that does not touch anything associated with any of the flocks directly. For example, do not dip food bowls into a bulk container; use a separate scoop instead. Likewise, do not interchange feed bowls among flocks without proper prior sterilization.

Note that the virus can be transferred for uncertain periods of time by people tainted with contaminants. Therefore, while the disease continues to proliferate, it is wise to limit visitors, especially those who have contact with other birds or wildlife. In the event visitation is necessary, provide guests with protective coverings before entering your flocks’ living spaces (boot covers, coveralls, gloves, etc.).

Avian flu can pass among various species, but it remains unclear how easily and which species present the greatest potential threats. The most obvious danger is birds, including ducks, geese, and other types. Do not allow flocks to have direct contact with other domestic or wild ones. Transmission can also occur from wild bird droppings, so limiting or preventing their exposure to domestic flocks is important. Regular cleaning or even covering open-air pens are critical measures.

Rodents and other non-avian species have also been known to spread the contagion, including back to birds, so make efforts to block them from entering pens or accessing food. Bear in mind that pets—cats, dogs, and others—can also contract avian flu, so protecting the flock helps protect them too.

Watch for signs of infection. While it will possibly be too late by the time signs or symptoms are witnessed, immediately separating potentially sick birds may nevertheless save at least some of the flock.

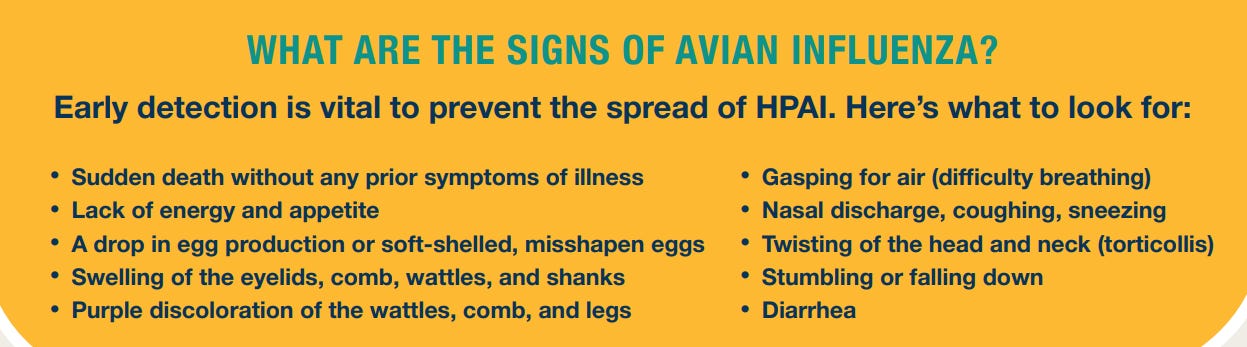

Source: USDA

The above list includes signs frequently seen among chickens infected with bird flu. PLEASE NOTE, identification of one or more of these does not positively indicate infection by any of the avian influenza strains. Nevertheless, under the circumstances, the presence of such signs should generate greater caution, closer scrutiny, and (possibly) reporting. Remember that in most cases of H5 or H7 infection, mortality rates are high and happen fast.

As noted, elements on the above list might indicate problems that are not the result of avian flu. For example, a reduction in egg laying can be caused by many things besides illness. Age of the egg layer, quality of food, weather, species, and light all may affect egg production.

Most species have laying cycles. During their lows, they may produce diminished numbers or none at all. Egg production sometimes reduces in winter because the shorter days (i.e., less available light) and cold weather both can affect the process of developing eggs. Heat stress can also negatively influence egg laying, especially in over-heated coops in winter. Some chickens reduce production in winter because they are kept in coops with too little space.

Torticollis (wry neck) can happen because of malnutrition or illness, such as Newcastle Disease. Infectious bronchitis can cause sneezing, gasping and coughing, or nasal discharge. Either of these afflictions (and others) can result in purple discoloration of the wattle, legs, or combs. Unexpected deaths among poultry also sometimes occur.

The point here is that while flock owners should exercise caution and watch for signs of illness, the presence of any of the above signs should not induce panic that the birds are infected with avian flu.

If bird flu is suspected, or you have concerns or want more information, the USDA recommends:

Contacting your agricultural extension office/agent, local veterinarian, local animal health diagnostic laboratory, or the State veterinarian, or call USDA toll free at: 1-866-536-7593.

Understanding the epidemiology of avian flu. Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Protect yourself

Human cases of infection by avian flu are rare, but not unheard of — at least 878 cases have been reported since 2003. Positive infection is very dangerous, however; the human mortality rate is around 50%. So far, transmission of the disease to humans primarily comes from handling sick birds. Airborne transmission is unlikely… for now. Although, one study reported:

Owing to similarities to humans in their susceptibility, ferrets are a valuable model in which to evaluate influenza virus transmission and pathogenesis, and ferrets are routinely used to assess pandemic risk…

To date, no subclade 2.3.4.4b highly pathogenic H5N1 virus has exhibited the ability to transmit by the airborne route, a feature thought to be critical in limiting their outbreak potential in humans. However, experimental studies have demonstrated the potential for an ancestral clade 2.1.3.2 H5N1 virus to become airborne transmissible in ferrets.

The vast majority of human cases are from contact with contaminated droplets in sputum, blood, or feces, which can travel 80 meters (87 yards) or more under ideal conditions. This is why handwashing, equipment sterilization, and general biosecurity is so important.

Considering the very high number of known cases of infected birds, the incidence of human infection is extraordinarily low at present. Thus, even chicken farmers who end up with a sick bird should not suffer too much anxiety. Nonetheless, because the illness is severe for humans, taking precautions is extremely important. And circumstances may change.

What happens next?

Medical professionals are preparing for the possibility of an increase in zoonotic (animal-to-human) transmission. While the scientific community has known of avian flu since at least 1955, and H5N1 since 1996, there are some noteworthy factors in its current spread that provide cause for concern:

This is the largest bird [flu] outbreak ever recorded historically. This scale of infection raises concerns about the potential for the virus to spread rapidly and have a significant impact on avian populations;

The current outbreak has seen a higher number of bird and mammal species being infected compared to previous outbreaks. This expanded range of hosts increases the potential for the virus to persist, evolve, and potentially cross species barriers, posing a threat to both animal and human health;

The wider geographic range of infections and the involvement of new species create opportunities for the emergence of new and potentially more dangerous variants of the virus;

The easy transmission observed between certain mammalian species, such as Spanish minks and Peruvian sea lions, raises concern about the potential for the virus to establish reservoirs in different animal populations and pose ongoing risks to both animal and human health.1

If people were mad about mandates during the COVID pandemic, they will really be mad about what will come if avian flu goes airborne and infects people en masse. Credit: screenshot from Global News report, October 17, 2020.

Viruses require compatible receptors to infiltrate host cells. Compatibility can be acquired through mutations. To head off possible disasters, such as outbreaks or pandemics, scientists study the types of mutations a virus might undergo through what some call ‘Gain-of-Function’ (GoF) research.

While some have criticized as too risky the concept of GoF following the SARS-CoV2 outbreak, researchers point out that critical advances are owed to it, such as the discovery of antibiotics and some cancer treatments, combatting antibiotic resistance, and preventing zoonotic spread of certain diseases.

(It is actually difficult to nail down what precisely constitutes GoF research, but a large portion of supposed GoF studies are not considered risky — see a detailed report on the issue here).

The H5N1 2.3.4.4b strain has shown a relative inability to infect humans on a massive scale, but a single amino acid mutation could change that. Scientists have identified a specific one they call Q226L. Biochemist James Paulson explained:

This mutation gives the virus a foothold on human cells that it didn't have before, which is why this finding is a red flag for possible adaptation to people.

In their study of the Q226L mutation, the researchers noted:

With the continuous and massive circulation of 2.3.4.4b viruses in both avian and mammalian species, it may be just a matter of time before different adapted gene segments collide. It is, therefore, vital to know which mutations in NA and HA are essential to adapt to the respiratory tract of humans. One such phenotype, human-type receptor binding, is described here, and we demonstrate that previously circulating 2.3.4.4e viruses only needed a single Q226L mutation to do so.

One variant identified among cattle in Nevada is an example of just the type of mutation about which scientists worry. It represents the first spillover of the H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, genotype D1.1, into cattle from birds. The USDA said in a statement:

While genotype D1.1 has been the dominant strain circulating in migratory wild birds across all four North American flyways during the winter of 2024-2025, these Nevada cases represent the first detection of a genotype other than B3.13 in U.S. dairy cattle.

University of Minnesota epidemiologist Michael Osterholm pointed out that this finding suggests that “the virus is not going away, contrary to those who thought B3.13 would burn itself out.” This is because it shows that the H5N1 virus is evolving, allowing it to infect mammalian species repeatedly, through differing variations.

Cutting off the defenders

The longer a virus spends within mammalian populations, the greater the chance that it will eventually mutate into something imminently dangerous to humans. This is especially concerning because the President of the United States — where H5N1 is proliferating the most and presents the greatest danger of triggering a human pandemic — has declared that the country will pull out of membership with the World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO coordinates the global response to health emergencies.

In addition to leaving the WHO, the President cut medical research funding distributed by the National Institute of Health (NIH), the world’s largest funder of biomedical research. A federal court temporarily blocked implementation of the cuts among states that joined a lawsuit filed in January. Nonetheless, the cuts could still happen as intended.

The Association of American Medical Colleges released a statement on the matter, saying:

The government’s support of facilities and administrative costs allows medical research to happen. These real and documented research expenses include physical lab operations and maintenance, security, data processing and storage, and daily operations of critical research infrastructure. Make no mistake. This announcement will mean less research. Lights in labs nationwide will literally go out. Researchers and staff will lose their jobs.

Dr. Andrea Love, an immunologist and microbiologist who also posts on Substack, outlined many of the items required to conduct successful research that will potentially lose financial support as a result of the President’s cuts:

access to computers, software, data analysis tools, journal subscriptions, libraries, animal facilities, veterinary care personnel, microscopy and imaging core facilities, genomics cores, flow cytometry cores, pathology facilities, clinical tissue banks….and yes, we do also need administrative support, finance teams, and legal teams.

She described in no uncertain terms where this will lead:

[I]f this is allowed to go into effect, a cap on indirect costs by the NIH will not only cripple US biomedical research, it will also make us sicker, worsen our healthcare, and cause serious economic damage to our entire country.

Notably, the NIH provided over $6 billion in funding to develop vaccines for COVID, which built on research previously funded by the US Department of Defense.

If the researchers who develop vaccinations and other preventive measures have their work shut down, avian flu will proliferate. Proliferation all but guarantees mutation until such time as it becomes a wholly human malady.

Currently, avian flu has a 1-in-2 mortality rate among infected people. It could grow worse if it jumps to humans. The “law of declining virulence,” or the notion that viruses evolve to become less lethal over time, is simply not true. Since the 1970s, scientists believe that the evolution of viral lethality is determined by “trade-offs” between virulence and transmission. Existing immunity and the availability of vaccines tends to lead viruses to favor transmission over lethality.

Massive public investment and coordination among researchers globally—helped in large part by the WHO—prevented the COVID pandemic from becoming far worse than it could have been. All of this is now at risk.

Gravediggers like these could become the next hot job in America. Credit: Gustavo Basso, CC BY-SA 4.0.

‘America First’ — but first what?

Attacking the science community through funding cuts and other political tomfoolery is not putting ‘America first.’ Shutting the doors on research labs could prevent scientists from getting ahead of further mutations of avian flu viruses (among others). This may open the door to another human pandemic, one far worse than the COVID saga.

If this happens with a pathogen that has a high transmission and mortality rate, mask mandates, lockdowns, and mass unemployment will be pleasant memories compared to what will come, especially under the ‘leadership’ that once called COVID — a disease that killed more than 384,000 Americans, and possibly as many as 3 million globally, in its first year — the “new hoax.”

Viruses do not respect national boundaries. Thus, ‘America first’ may come to mean the first country to suffer catastrophe and mass death under the crushing weight of the next pandemic, one that this inept administration is all but inviting.

** Articles post on Saturdays. **

If you found this essay informative, consider giving it a like or Buying me A Coffee if you wish to show your support. Thanks.