The Psychology of an Email Attack

A multi-million-dollar firewall can be defeated by a single employee

Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

In 2014, Aleksey Belan, a Latvian hacker working as a contractor for Russian Cyber Intel, sent a spear-phishing email to a Yahoo! employee. What happened next was a series of events that led to the compromise of up to 3 BILLION accounts. Cyber experts generally define spear-phishing as a “targeted attack… addressed directly to the victim to convince them that they are familiar with the sender.” Spear-phishing attackers research their targets through social media and other open-source methods to craft a highly convincing—and extremely effective—message. This message tricks the user into doing something: often clicking a link or opening an attachment to provide an opportunity for the attacker to gain access to the target network. In the Yahoo! hack, the attacker gained access to the network through his spear-phishing message. Once in, he found the user database and the Account Management Tool, where he acquired information such as names, phone numbers, password challenge questions and answers, and recovery information for billions of accounts. After gaining access, Belan also installed a back-door that provided him continued access to the network, and eventually downloaded an entire backup copy of Yahoo’s userbase, gaining access to the content of billions of email messages. The fiasco cost Yahoo! over USD 117 million.

Spear-phishing is so effective because the attack method— sending emails to users on the target network—is carefully crafted to appear as authentic as possible. Because most people are on social media, either themselves or by proxy through family and friends, a clever OSINT researcher can find plenty of information to create very convincing messages. Add to that the ability to spoof email messages, and an attacker has a very powerful tool at his/her disposal.

Spoofing means disguising the true information behind an email. This might be as crude as generating an email with a spelling very similar to the authentic email address by exchanging one character for another. One might look as follows:

Real address: myboss@work.com

Fake address: myboss@w0rk.com

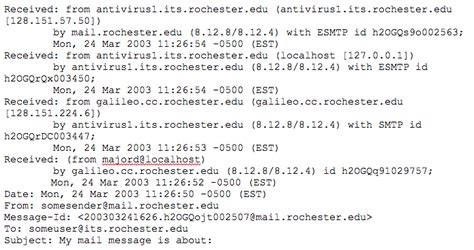

More advanced techniques for spoofing are possible through freely available tools online. These tools allow someone to create the appearance of (almost) any email address, and they route traffic through the tool’s proxy server back to the attacker’s real address. From the victim end, the email might look wholly legitimate, even possibly appearing as an email from within their company’s domain, but the underlying data found in the header will reveal that the traffic to and from this address actually goes somewhere altogether different. In other words, the text of the email will appear as if it came from myboss@work.com, but the header will reveal that the return path for a reply goes to something like hacker@34343.com. Put simply, what the user sees in his/her usual email client is falsified information to cover the real data. An email header looks like this, (source tech.rochester.edu):

Unfortunately, very few user-employees will ever look at this data. User complacency or unawareness is a big reason why these attacks are so effective.

Certain employees are especially vulnerable. A study conducted in 2015 by the USC Viterbi School of Engineering's Computer Science Department found several trends that are instructive on how email users fall prey to spear-phishing. The study examined the time it took for users to reply to email messages. Logically, swifter reply times suggest that the user is paying less attention to the potential illegitimacy of any specific message. The study found that younger users tended to reply more swiftly than older users. Emails received on and replied from a mobile device showed the shortest turnaround time of all, irrespective of the demographic of the user. Employees who hold busy schedules or send and receive high volumes of emails are among the most vulnerable group to phishing attacks because they are less likely to pay close attention to individual email messages, especially those appearing legitimate at a glance.

Now, imagine an attacker who has done a lot of homework. Having created a spoofed address to look like someone from within the victim’s own company, the attacker selects an employee whom he knows handles a large volume of emails, is younger, and is at least somewhat likely to receive and respond to emails on a mobile device. By acquiring a good amount of information about his victim as well as the person the attacker himself is pretending to be, the attacker sends an email with a hint of urgency. It asks the user to click a link or open an attachment for some reason—either of which contains malware that will create a vulnerability on the company’s network. The chances that his victim might respond by clicking a link or opening an attachment will have grown substantially because of the research the attacker has conducted. The result could be similar to what happened to Yahoo! in 2014 (and many thousands of companies since then).

The situation is not hopeless. Companies can take several measures to mitigate this threat, both technological and psychological. On the technological side, companies should keep and maintain robust security measures. Hackers are often lazy. They frequently use known malicious programs or links that many security systems can detect. Keeping the company’s security up-to-date with vigorous detection measures will all but prevent lazy hackers from succeeding. Implementing security protocols that compare display names to reply path names should immediately identify many spoof attempts. Security should also detect and notify users of possible re-directs in the reply. (Note that sometimes this is legitimate, but at least identifying them will increase the chance that proper attention is paid). Even adopting the simple measure of always-on spellcheck on emails can assist users with identifying unusual or suspicious email messages.

Other methods combine technological with psychological. One example is creating pop-up notices asking if a user wishes to engage in the desired activity—such as clicking on a link. Such a pop-up could emphasize the danger in doing so, which often will give the user a moment to reconsider his or her next move. Another pop-up should indicate to users unusual days or time of emails. If, for instance, a user receives a “security check” supposedly from the company’s IT department at 4 am, a pop-up noting the odd time of this message might make a user think twice before acting. Some firms also identify emails that have similar domain names as the company and flag them to the user. This helps identify spoofed emails using misspellings in the email to or from category. Sending regular phishing attempts to employees by in-house cybersecurity is also a great way to alter the psychology of employees. Employees who succumb to such ‘attacks’ should receive a second email later, identifying how they fell for this tactic. In business, people are often competitive and do not wish to “lose” to other employees by being the one who was duped by a fake phishing attempt. Even though other employees would not even know it happened, the “victim” will tend to think twice about the next message for fear of being the only one foolish enough to fall for it. Still others might fear they could lose their job if fooled enough times, and will therefore pay closer attention.

In addition to these methods, policy requirements can greatly enhance resistance to potential attacks. A commonly adopted policy now involves password protection. Many companies enforce password changes every 30 to 60 days. While this annoys employees, it nonetheless provides an important security measure. Policies should include prohibitions against:

using previous passwords

using passwords set for other company programs

using common passwords or dictionary words

using passwords of fewer than 11 characters, or without special characters

using passwords with too many repeated keys

using passwords that the employee uses in their personal accounts

The misstep in using previous passwords is obvious, but many companies still do not forbid the use of passwords that employees are currently using for other systems. Employees should not be allowed to use the same password for logging into their computer, email, and a customer database, for example, no matter how complex the password. In terms of complexity, employee passwords should be at least 11 characters long, forbid common words, and prohibit repeated keys (such as Wer23cd!!55551). In brute force attacks, repeated keys and dictionary words can be guessed much more quickly, which reduces the efficacy of a long password. Moreover, a longer unique password can add months, years or even centuries to the amount of time it would take a brute force program to guess. Thus, the policy should require a minimum of 11 characters, and encourage going even higher.

Some companies also use disable or quarantine policies for external links and attachments in emails. External links can be disabled so that a user cannot simply click the link and go to the website. Another method prevents copying and pasting external links. This then forces the employee to manually type the URL into the address bar. Doing so necessarily causes the employee to think about it before just following the link. Many employees simply will not bother typing it out of laziness. Furthermore, if employees know that only internal links are readily clickable, they will proceed with greater caution with links that cannot be clicked.

For attachments, many companies employ a quarantine where the employee must request release of attachments from external senders. This enables IT Security to analyze files before releasing them. Files flagged as potentially malicious or executable require further steps before the IT Security will release it to the employee. One agency with which I am familiar allowed users to identify “trusted entities” where attachments from certain external senders identified by the user were treated like internal senders, but the header details had to match in every case or the attachment would automatically enter quarantine.

Perhaps the most important policy is conducting frequent training. Human beings become complacent when things are going well, which is exactly when they become most vulnerable to attack. Performing regular training helps keep employees on guard for possible attacks, and makes them aware of new attack tactics identified by law enforcement, researchers, or other authorities. A key part of training is making sure employees know what the company’s security policies are and articulating to them their specific responsibilities as part of the security infrastructure. This is too often ignored. Training should also cover old attack methods as well as new ones. Include many examples, especially those in which a company suffered significant damages as a result of an effective attack. Good trainers provide numerous ways to identify fraudulent emails, links or attachments, and help to instill some common-sense thinking. Many employees who succumb to attacks later admit to having “had a bad feeling” about something, but did not pay enough attention to their suspicion to prevent their vulnerability. Proper training can prevent that.

Technology provides one important aspect of the defense of company information, but the human element cannot be ignored. Without proper training, employees will undoubtedly be the major weak point in a company’s defenses.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run the EALS Global Foundation non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

For more on cybersecurity, see below.

How Strong are your Passwords?

In today’s world we all have so many passwords. Banking, social media, email, online retailers, employment… so, so many. It is hard to keep track of them all. Yet, the password remains the primary point of security for a great many things we wish to protect. Heck, there is even a thing called the

Saturday Shorts: VPNs

A Virtual Private Network (VPN) is basically a piece of software that tunnels your internet traffic from your device to a VPN server, then out to the internet. VPNs encrypt your data and prevent your Internet Service Provider [ISP] (and others) both from reading that data and from seeing where it goes onto the internet. The only thing the ISP knows is t…