The Origins of the World's most Mysterious Book

Installment 3 - Tracing the history of the Voynich Manuscript

Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here. Be sure to read the other articles in this series.

Where did it come from?

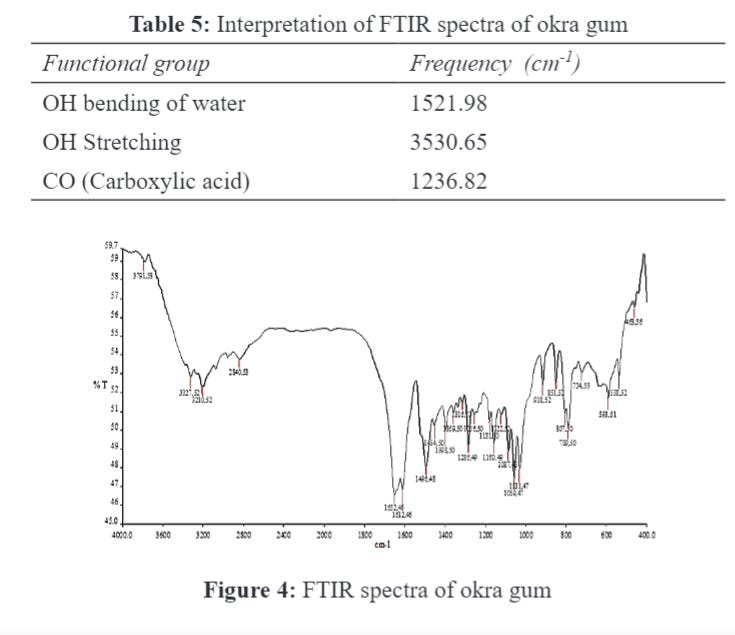

The Voynich Manuscript—the world’s most enigmatic text. Researchers have assumed a European origin given what is known of the historical geographical trajectory of the Voynich Manuscript (VMS). Wilfrid Voynich—for whom the manuscript is named—himself never said precisely where he acquired the manuscript. To clarify, he did not write it. Voynich was merely a rare book collector who stumbled across and ultimately acquired the work in the early 20th century. René Zandbergen provides a detailed account of Voynich’s comments and writings about his acquisition of the VMS here; this section borrows extensively from there. To begin, Zandbergen summarizes several newspaper reports on Voynich’s exhibitions of his collected works:

During research, Voynich found evidence, possibly in some old correspondence, of a collection of manuscripts hidden in Austria. These were manuscripts from ducal or princely libraries, which were taken abroad during Napoleon's invasion into Italy, in order to prevent that they were taken to Paris by Napoleon. After some detective work, Voynich found the chests in a castle in Austria, or a castle of an Austrian nobleman. These chests had not been opened for more than a century, and their owners or guardians had no idea what they contained. Voynich obtained the rights to them, also because the original owners had all died and the collection(s) had been forgotten.

Voynich’s purpose in keeping the location a secret purportedly had to do with his desire to obtain more works from the place. Whatever the reason behind his secrecy, bibliographic slips discovered in 1937 show that the works Voynich acquired, including the VMS, previously belonged to the Society of Jesus. Before then, various royalty figures owned the collection as has been proved by scholars; these include: Alfonso of Aragon (1396 – 1458), Borso D’Este (1413 – 1471), Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta (1417 - 1468), and Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary (1443 – 1490), among others.

On the rosettes page within the VMS, an image of a castle comports with the building style of structures from Northern Italy in the same time period. A drawing depicting swallow-tail or ghibelline crenellations is consistent with buildings from the Verona region beginning in the 14th century. Nick Pelling has identified some historical European texts from which to make further comparisons: (1437) “De Laudibus Mediolanensium urbis panegyricus” by Pier Candido Decembrio (mentioned in Boucheron p.74), Bernardino Corio’s “Storia di Milano,” and “Lavori ai castelli di Bellinzona nel periodo visconteo,” Bolletino della Svizzera italiana, XXV, 1903, pp.101-104. Nevertheless, the artistic style may have more to do with the identity of the author than the place of origin of the work if the image was not meant to depict a specific structure. Other architecture illustrated in the VMS still requires expert analysis.

Some of the other features of the manuscript support a European origin, but further confuse precisely which place(s). For example, Sergio Toresella, a historian of botany, has identified certain herbal drawings as consistent with the style of artists from Northern Italy in the mid-1400s. In the zodiac section, there is a drawing of a Sagittarius formulated in a way commonly found in German manuscripts between 1400 and 1500. The zodiac fish—presumably Pisces—face the same direction, similar to those drawn in the Codex Schürstab (Nürnberg), commissioned by Erasmus of Rotterdam (ca. 1466–1536), and like to those in the 15th century Book of Hours thought to be from Nantes, France. A depiction of Aries the Ram also looks somewhat similar to that illustrated in the Codex Schürstab. Apparent abbreviations next to the Virgo illustration in the VMS utilize the same conventions found in other works, such as the Codex Manesse, created in Zurich. The archivist of the Strahov library in Prague, J. Parez, has commented that the writing style is reminiscent of Italian style, but that some passages indicate hints of German and Latin from the era before 1550. From this, some have characterized the script as ‘Alpine.’

In addition to the primary stylistic content, the VMS contains what has been called “extraneous writing.” Throughout areas of the text are letters and possibly words that seem “scribbled” in the margins. Many of these sit beneath painted images, indicating they were there before the painted images were added. Scholars compared these to manuscript 362 of the Biblioteca Civica Bertoliana in Vicenza, which contains somewhat similar annotations to its images. Some of the extraneous writings in the Voynich manuscript appear to be in German, consistent with the written language in use between 1430 and 1450. One example includes the phrase “der Musdel,” which many think is German and others Dutch, though scholars do not understand the meaning in either case. The conclusion most have drawn from this is that the original scribe(s) was at least literate in German, if not from there. In total, the composer(s) of the VMS at least seemed to have reasonably widespread knowledge of contemporaneous texts from various parts of Europe.

The Date

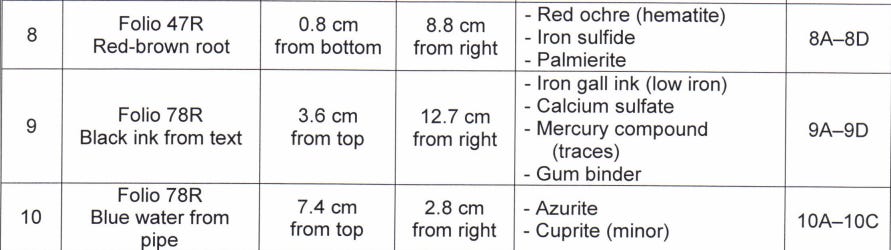

In 2009, McCrone Associates, Inc. performed a “materials analysis” of the manuscript. Researchers began by acquiring samples from various places within the manuscript and applying several different examination techniques. See the table below for the color and items, locations, and the identified constituent materials.

The firm concluded through carbon dating with 95% certainty that the parchment dates from 1404 to 1438. Carbon dating works by measuring the rate of decay of two specific carbon isotopes. While a creature is alive, it typically has the same ratio of 12C and 14C as its environment (where here the 12 and 14 represent individual isotopes). When an organism dies, it no longer consumes material from its environment—meaning, it no longer eats, drinks, or breathes—and this leads to the breakdown of the isotopes. Carbon-14, however, decays at an exponential rate while carbon-12 does not. This allows scientists to measure the ratio difference to determine the time that the 12C and 14C were the same, allowing them to calculate backwards based on the known rate of decay of 14C. To enhance the accuracy of the measurement, scientists use calibrated computations which take into account certain events in history (such as nuclear detonations of World War II and subsequent testing) that have affected the global presence of each isotope within living creatures. Multiple examinations of various sections of the manuscript, calculated using both calibrated and uncalibrated methodologies, led to a statistical result of 1434 ± 18 years, with a corresponding 14C fraction of 0.9379 ± 0.0021. An independent analysis of these results using an IntCal04 calibration curve led to nearly identical results. Of note, it appears that the physical materials used for the paper and binding are of average quality. Microscopic analysis did not uncover erasures or previous writings overwritten by the current text. Multispectral analysis confirmed this conclusion. Moreover, every page appears to have been manufactured concurrently. As a last note, carbon dating only works on items made of organic substances.

The Ink

McCrone Associates also conducted a thorough analysis of the ink used for the writing. All ink samples were examined with polarized light microscopy (PLM). PLM works this way:

The polarized light microscope is designed to observe and photograph specimens that are visible primarily due to their optically anisotropic character. In order to accomplish this task, the microscope must be equipped with both a polarizer, positioned in the light path somewhere before the specimen, and an analyzer (a second polarizer), placed in the optical pathway between the objective rear aperture and the observation tubes or camera port. Image contrast arises from the interaction of plane-polarized light with a birefringent (or doubly-refracting) specimen to produce two individual wave components that are each polarized in mutually perpendicular planes. The velocities of these components, which are termed the ordinary and the extraordinary wavefronts, are different and vary with the propagation direction through the specimen. After exiting the specimen, the light components become out of phase, but are recombined with constructive and destructive interference when they pass through the analyzer.

Polarized light microscopy is capable of providing information on absorption color and optical path boundaries between minerals of differing refractive indices, in a manner similar to brightfield illumination, but the technique can also distinguish between isotropic and anisotropic substances. Furthermore, the contrast-enhancing technique exploits the optical properties specific to anisotropy and reveals detailed information concerning the structure and composition of materials that are invaluable for identification and diagnostic purposes.

Researchers determined that most of the ink samples possessed very similar chemical compositions. They typically contained iron, sulfur, calcium, potassium, and carbon, with trace amounts of copper and, even less so, zinc. The primary ingredients are routinely found in iron gall ink, though the presence of copper and zinc are unusual. Nevertheless, there are some explanations for these odd elements, but their source remains unknown. All the inks used for the text matched that of the ink used in the drawings, with the small differences among them common among iron gall inks of the 14th and 15th centuries. These researchers concluded that the drawings and text were most likely composed around the same time. A few samples, though, contained larger amounts of iron, suggesting that those inks were from a different ink source. In sum, the authors of the ink analysis study reached the following conclusions:

The ink used for the text is the same as that used for the drawings; both are iron gall inks;

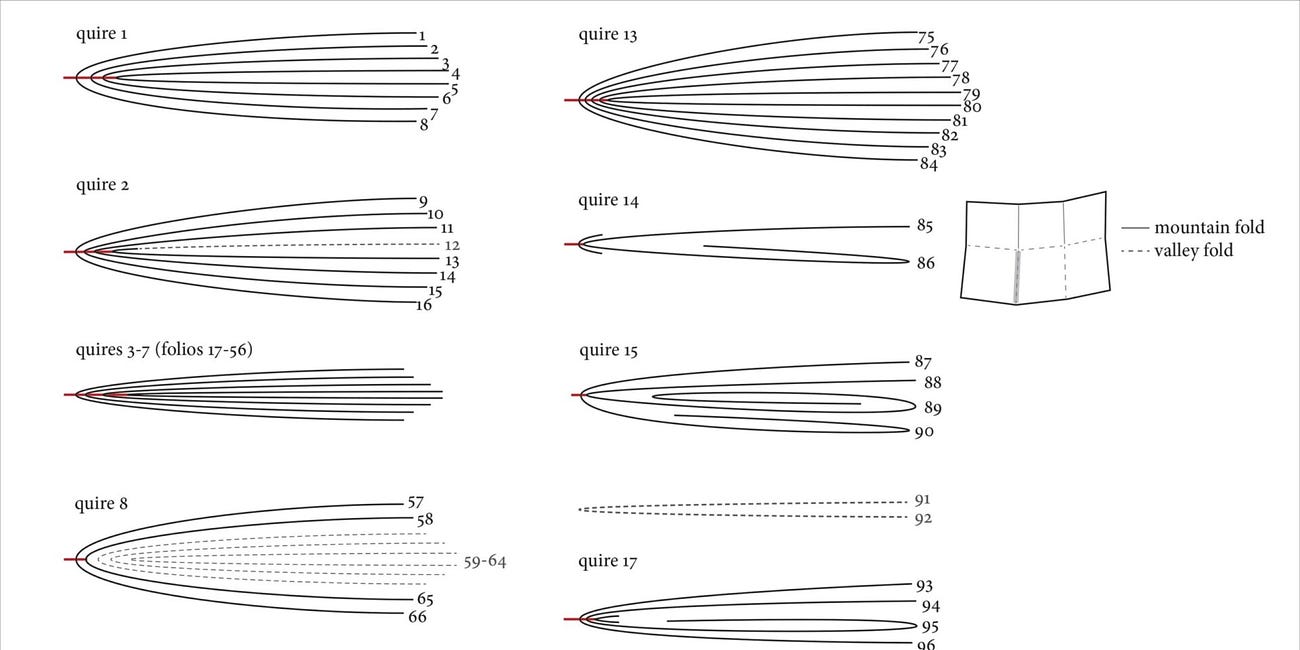

The ink used for the page numbers, the quire inks, and the ink used to write the Latin alphabet on f1r are all different from the text/drawing ink, and from each other;

The binding medium for all inks is gum.

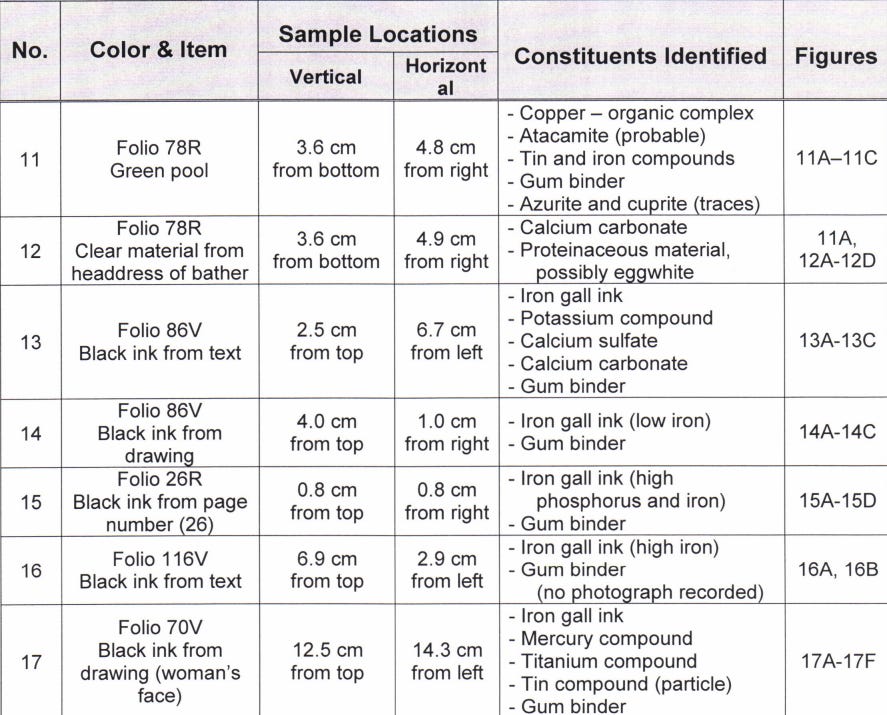

Regarding the final conclusion, iron gall inks typically used gum Arabic during that time, but infrared spectroscopy of the gum used in the VMS identified peaks inconsistent with known samples. It is possible that the gum was made up of other constituents for which these researchers did not test. One example could be okra gum, which resonates near the frequency level of the peaks seen in this study. See this FTIR spectra analysis as an example:

Source: Extraction and Characterization of Okra and Almond Gum as a Pharmaceutical Aid

The ink analysis does not provide any specific detail alluding to the scribes themselves as this kind of iron gall ink had been in use for centuries before and after the carbon dated timeframe of the parchment. The presence of unusual constituents may help narrow the geographic location where the ink was created, but much further study is needed. No constituent material in the ink mixture was inconsistent with the carbon dating of the folio, though, suggesting that it is likely that the ink used was relatively contemporaneous to the dating of the paper.

A firm confirmation of the date informs the contextual materials researchers should examine to assist with unlocking various aspects of the VMS. In employing AI in particular, it is useful to have a narrowed date range for the creation of the content of the VMS because this will help decide what materials should be included in any AI training set. One of the first uses of AI toward analyzing the VMS suffered from employing modern-day information into its dataset, specifically modern languages. Considering the historical framework in which the scribe(s) drafted the VMS will greatly enhance any sophisticated examination of the document.

Conclusion

Taken together, the evidence strongly indicates a European origin sometime from 1404 to perhaps the end of the 15th century. Operating from this evidence-supported assumption, scholars have employed numerous comparative studies of texts from the same time period, including non-European sources. With the explosive growth of computing power available to researchers, I am confident that eventually the code of this mysterious manuscript will be cracked.

To read the other entries in this series, click below.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run the EALS Global Foundation non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

I really love the facts you put in quick succession versus video documentaries that get boring..

Thanks for another great morning read.