The Curious Construction of a Mysterious Book

Installment 2 - the physical layout

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages, which includes the latest podcast episode; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share! Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

***

Introduction

The text and images of the Voynich manuscript (VMS) have stirred up intrigue for over a century. What the heck does it say? Why can no one seem to decipher it or break its code (if there is one)? Is it even a language at all? Arriving at answers to those questions requires ingenuity and scrupulous research. Developing creative and innovative approaches toward deciphering the manuscript is challenging as its contents have been under scrutiny by so many for so long. For that reason, many scholars have taken a holistic approach. Like investigating a criminal case, one can never know what clue or clues might ultimately provide the key piece of evidence to crack the case. Unlike certain criminal cases, however, here we have possession of the critical piece of evidence—the manuscript itself—enabling a detailed evaluation of any proposed solutions. That is why it is crucial to assess every element of the VMS, for the keys to the mystery almost certainly lie within it.

Today, I discuss the physicality of the manuscript. Its construction already has offered significant clues about its place and time of origin, while also hinting at who may have written it. Furthermore, its physical construction should influence any analysis of its contents. I explore the reasons for this below.

The Physical Book

René Zandbergen notes that the current cover of the VMS is not the original. Scholars instead have identified its origin to between the 18th and 19th centuries, several hundred years newer than the pages of the text. In fact, the cover closely resembles others made by the Jesuits of the Collegium Romanum, where the manuscript was believed to have been stored for a long time, providing further evidence supporting the currently understood historical trajectory of the text. The cover of the manuscript now is made of goat skin. Discoloring on the edges of the first and last folio suggests that it was previously bound with wood covered by tanned leather.

The VMS is made up of about 240 calfskin parchment pages, measuring roughly 225 x 160 mm (8.8 x 6.3 inches). It is divided into 18 quires (with 2 more believed to be missing), and further organized into 102 folios (also presumed to be missing 14 more). Quires are described simply as “A collection of leaves of parchment or paper, folded one within the other, in a manuscript or book.” Most of the VMS’s quires consist of a stack of four sheets, folded in the middle to form 8 folios. Some of the folios fold out into larger pages. These contain drawings or writing (or both) on each side. Zandbergen describes the manner by which most scholars refer to the various sections of the manuscript:

[T]he individual sides of each folio will be referred to here as a 'page'. Thus, a standard quire has 16 'pages'. The notation used to identify a 'page' in the Voynich MS follows standard usage, namely the character "f" (for folio), followed by the folio number, followed by either "r" (for recto - the front) or "v" (for verso - the reverse). Thus, the first quire starts with 'pages': f1r, f1v, f2r, f2v, f3r, etc, and ends with f7v, f8r, f8v. The 'pages' f1r, f1v, f8r and f8v together form one bifolio.

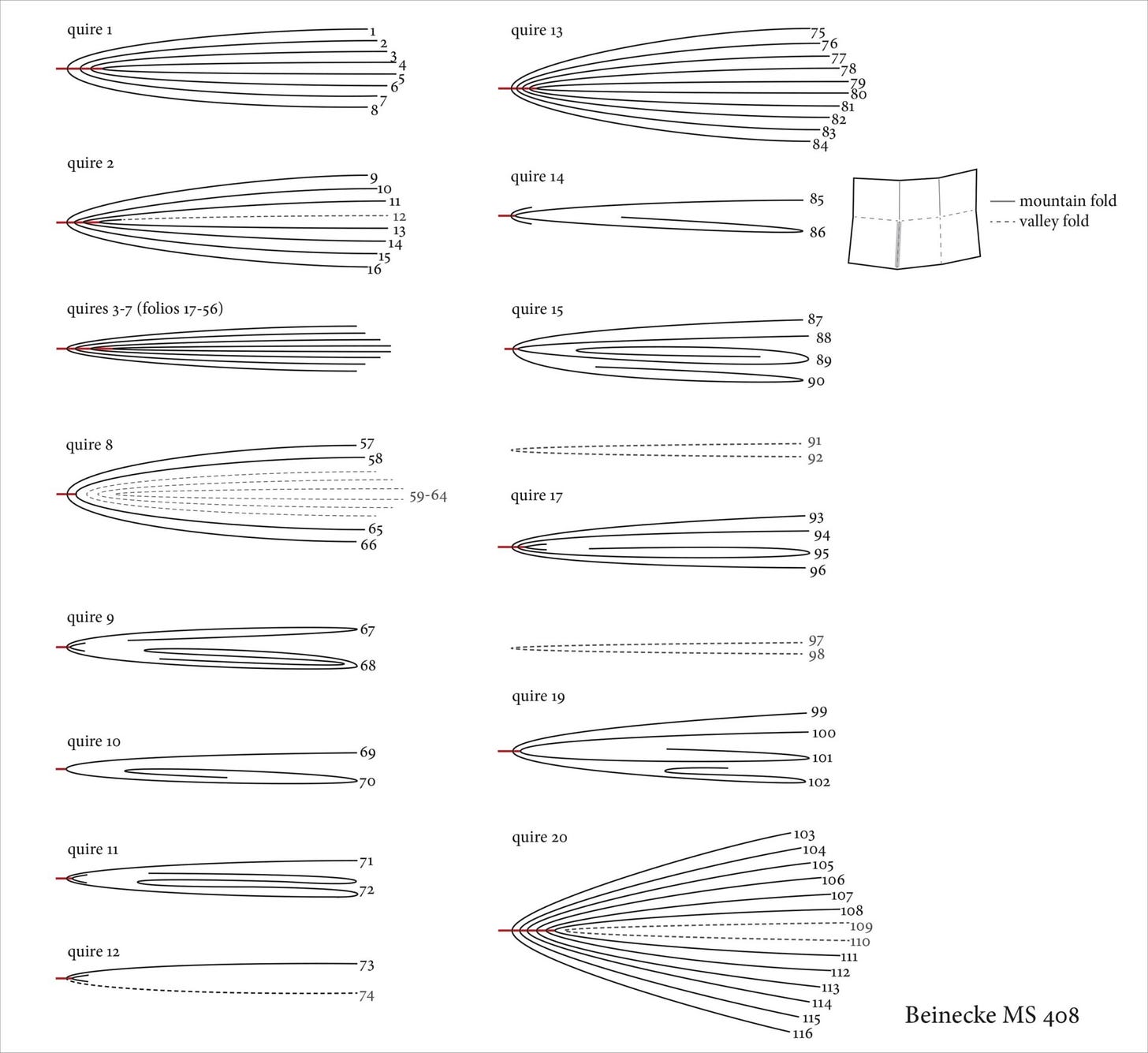

Any references in this series will follow that paradigm. Yale University Press has provided a helpful illustration of the physical layout.

Physical layout of the Voynich Manuscript; source: Yale University Press

As the image shows, the manuscript unfolds in a variety of different ways, a rather unusual feature compared to contemporaneous documents. Each folio contains a number in its upper right corner. The numbers of the missing folios are skipped, which suggests that the numbering was added later, even though the numerical characters themselves are old. Moreover, chemical analysis indicates that the ink used for the page, folio, and quire numbers differs from the ink used for the text and drawings. It seems that the addition of these numbers, regardless of how long after the construction and completion of the full manuscript, does not help much with identifying the original writer(s), but may indicate that any out-of-order sections still ‘belong’ where they are.

The numbers (both present and skipped) and the missing quires and folios show that the current ordering of the manuscript may not match the original. As Zandbergen points out that whoever added the numbers appears to have known of the missing sections. He adds, “The most logical assumption is that they were not missing at the time. How else could the foliator have known which ones were missing?” But this is not the case in every place. In quire 8, for instance, Zandbergen identifies only two bifolios. The numbering there goes from 58 to 65, however, alluding to the fact that five bifolios probably once resided there (see image above) but disappeared later.

In addition to missing pieces, the ostensible content also suggests that the order now does not match the original. For example, there is a long herbal section (based on the imagery), followed by several other topical sections, followed again by another herbal section. This latter herbal content appears quite similar to that of the first herbal section. Regarding the opening herbal section, the first twenty-five folios are written in one hand (and in one apparent “language”). The next twenty-five sections, though, are written by at least two different people. They are also written in two “languages,” each clearly penned by different scribes. Note that this was not unusual for medieval manuscripts, which sometimes took decades to complete. Upon further analysis of the rest of the VMS, Zandbergen concludes that while the entirety of the manuscript was composed in a total of two “languages,” it appears likely that these may have been written by as many as eight different “hands” (or, people). Zandbergen clarifies what he means by “languages” here:

Before I go on, the characteristics of ‘‘languages’’ A and B are obviously statistical… Suffice it to say, the differences are obvious and statistically significant. There are two different series of agglomerations of symbols or letters, so that there are in fact two statistically distinguishable ‘‘languages.’’

This will be a very important consideration in the discussion of possible analyses, forthcoming in other articles.

While this essay is about the physical construction of the document, the content discussed herein matters because the organizational features most certainly must be taken into consideration when determining how to approach any attempts at deciphering the text. To compare, in analyzing the notes of Leonardo Da Vinci, the process might quickly be derailed if unable to recognize that the language he used normally goes from left to right; but he wrote his notes in the reverse. Had he composed this “mirror text” in an unknown language or characters, following a non-standardized justification format, analysts might have misapplied the notion of “words” to specific clumps of characters, or confused even the composition of the individual characters themselves. Add to that a fundamental re-ordering of the overall content, and the potential for misreading even the statistical features of the text may have increased. In a future installment, I will discuss how scholars so far have approached this problem in relation to the VMS, and will offer my own input. Turning to Zandbergen one last time, he offers this warning:

Anyone who attempts to work on the text without considering these, ignores them at his own peril…

How important the reordering is in interpreting the text is not fully known. The evidence suggests that the various folio and quires—if indeed reordered—were reconstituted very near to the time of the manuscript’s creation. This indicates that the order now may not impact analysis of the content, sort of like rearranging paragraphs in a textbook’s second edition. Still, a proper analysis of the content must remain cognizant of this and avoid making any unfounded assumptions.

The Date

In 2009, McCrone Associates, Inc. performed a “materials analysis” of the manuscript. The firm concluded through carbon dating with 95% certainty that the parchment dates from 1404 to 1438. Carbon dating works by measuring the ratioed rate of decay of two specific carbon isotopes. While a creature is alive, it typically has the same ratio of 12C and 14C as its environment (where here the 12 and 14 represent individual isotopes). When an organism dies, it no longer consumes items from within its environment—meaning, it no longer eats, drinks, or breathes—and this leads to the breakdown of the less stable carbon-14. This allows scientists to measure the ratio difference to determine the time that the 12C and 14C were the same, allowing them to calculate backwards based on the known, constant rate of decay of 14C. Carbon-12 remains constant in an organism, even after death, which provides the objective value by which to measure.

Carbon-14 enters the systems of living creatures as carbon dioxide. The level of carbon-14 absorbed at any given time is determined by atmospheric events (such as the collision of cosmic rays with nitrogen-14 atoms). Scientist know these levels based on the measurement of any number of once-living entities (plants and animals), but some world events have contributed to artificial alterations. They have, nonetheless, figured out methods to enhance the accuracy of the measurements. One method is to use calibrated computations which take into account certain events in history (such as nuclear detonations of World War II and subsequent testing) that have affected the global presence of each isotope within living creatures. Multiple examinations of multiple sections of the manuscript, calculated using both calibrated and uncalibrated methodologies, led to a statistical result of 1434 ± 18 years, with a corresponding 14C fraction of 0.9379 ± 0.0021. An independent analysis of these results using an IntCal04 calibration curve led to nearly identical results. You can read the analysis report on the VMS here.

On a final note, it appears that the physical materials used for the paper and binding are of average quality. Microscopic analysis did not uncover erasures or previous writings overwritten by the current text. Multispectral analysis confirmed this conclusion. Moreover, every page appears to have been manufactured concurrently.

A firm confirmation of the date informs the contextual materials researchers should examine to assist with unlocking various aspects of the VMS. In employing AI in particular, it is useful to have a narrowed date range for the creation of the content of the VMS because this will help decide what materials should be included in any AI training set. As mentioned previously, one of the first uses of AI toward analyzing the VMS suffered from employing modern-day information into its dataset, specifically modern languages. Considering the historical framework in which the scribe(s) drafted the VMS will greatly enhance any sophisticated examination of the document.

***

This is the second installment of my Voynich Manuscript series wherein I dissect the scholarship on this enigmatic text. These beginning pieces are meant only as an introduction to the manuscript itself. Soon, this series will start delving into more complex analyses both to introduce the reader to interesting scientific methodologies, and to work toward formulating the plan by which my students and I will propose new applications of technology toward examining various aspects of the VMS.

Click here for the first installment:

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run the EALS Global Foundation non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.