No Ice, No Water

Swiftly diminishing glaciers ring (yet another) climate catastrophe bell

Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages, which includes the latest podcast episode; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

In November, I published a piece about the extreme consumption habits of the tech industry, particularly cryptocurrency and artificial intelligence. While agriculture and industry for now consume the vast majority of water resources on the planet, the growth of these tech sectors promises to start cutting into those numbers quickly. For example, data centers powering AI evaporate more water than the African country of Liberia (population 5 million) draws in an entire year. In 2022, water intake by Microsoft and Google grew by 34% and 20% respectively, with Microsoft consuming nearly 1.7 billion gallons alone. The growth in these consumption rates comes at the same time as a key resource for providing freshwater continues to shrink at alarming rates—Glaciers.

The Himalayas

I have written previously on the rapidity with which Himalayan glaciers are shrinking:

Accelerated warming has had an acute effect on the state of Himalayan glaciers. Between 1970 and 2000, 9 percent of the ice disappeared, and between 2003 and 2009, 174 gigatons of water were lost each year. That number is near impossible to visualize—it is 174 billion tons. Put another way, if this amount were distributed to every man, woman and child in India, each person would receive around 123 gallons of water each year. One study published in 2021 found that contemporary loss of glacier mass in East Nepal and Bhutan has accelerated ten-fold compared to any long-term assessment of previous fluctuations since the Little Ice Age.

The Himalayas feed water to regions spanning from Afghanistan to as far east as Myanmar (f.k.a. Burma). Scientists say that the ice melt in the region has occurred faster than any other place on Earth over the same time. Even the most stable glacial area in the region to date—the Karakoram range in Pakistan—has since begun eroding despite ice-mass gains in previous decades. At its current rate of melt, and assuming the world does little to curtail its contribution to causal factors of global warming, as much as two-thirds of the remaining glaciation in the Himalayas will probably disappear.

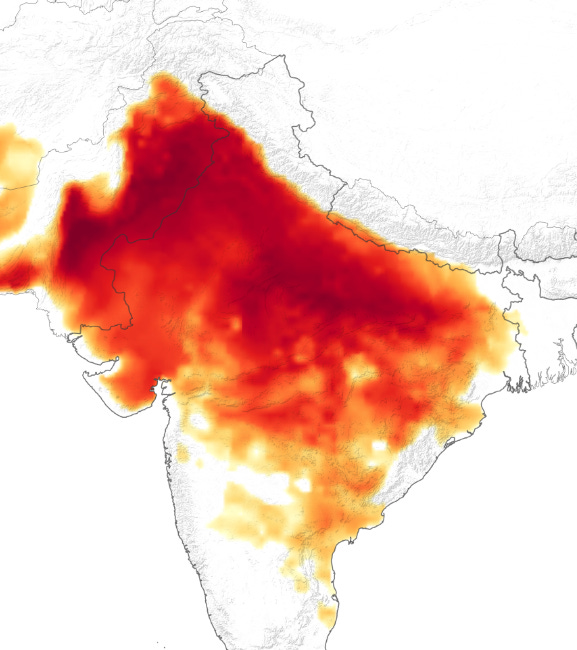

That level of ice loss will have a profound effect on the lives of over one billion people. Rivers that provide primary sources of drinking water receive their supply from the cyclical melt and refreeze of Himalayan glaciers. These include the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra rivers. Reducing the availability of fresh drinking water to such a large number of people will lead to unimaginable consequences. This is especially so as much of that region already faces near unlivable conditions due to rapidly rising temperatures year-upon-year. As drinking water disappears, food production will also decline. Farming in the Himalayan region also depends on these annual cycles for survival. For some areas, snow-melt runoff comprises as much as 72% of total water requirements to cultivate crops, particularly in the upper Indus area. As temperatures heat up annual snow melt decreases, and both exponentially contribute to droughts that only further exacerbate the overall problem. In the Tarai region (which includes northeast India and southern Nepal), farming has endured enormous difficulties. On this, I wrote:

Increasing temperatures has had a significant effect on farming in the Tarai in several important ways. First, as average temperatures rise, the way rain falls has changed. From 1986 to 2006, Nepal saw an overall increase of 163 mm per year of precipitation, with all of it occurring during the monsoon season, while rates have been decreasing in the winter months. Since 1990, incidents of rainfall typically comprise much heavier rains followed by longer, drier periods between. Heavier rainfalls tend to run off, leading to lower levels of soil saturation. Limited saturation in summer and decreased precipitation in the winter months has exacerbated drought conditions, and contributed to more incidents of fires. Drier surface conditions create an environment for fires to easily start and spread, while less water makes extinguishing fires harder. As fires ravage agricultural areas, themselves diminished in size by urban sprawl, the sustainability of the soil lessens for some time, thereby reducing output. These combined factors may require a significant shift in the choice of crops in order to adapt to changing circumstances.

Water crises lead to food crises; the two combined lead to full-blown catastrophes. All these problems feed upon each other. Warming temperatures reduce glaciation and runoff volume, which in turn lessens the supply of water for drinking or irrigation. At the same time, warmer temperatures increase the number of heavy rainfall burst events, but weaken normal precipitation patterns, leading to decreased soil saturation and higher vulnerability to wildfires. As unsaturated soil and unusually high temperatures increase fire risk, and rising numbers of fires further decrease agricultural output, when coupled with diminishing water supplies the food crises intensify. And all this occurs in the midst of the degradation of survivability conditions induced by continuously record-breaking temperatures.

Depletion of river flows may also curtail electricity output from hydroelectric dams. Nepal, for example, generates the vast majority of its electricity from these projects. India, so far, has only developed around 30% of its hydroelectric potential, but is seeking to increase that number to replace fossil fuel and other climate polluting energy sources. Nepal could could see its electrical grid drastically disrupted as rivers dry up. India may opt to continue relying more heavily on coal than hydropower, thereby exacerbating these issues by further contributing to the underlying causes of them. In both countries, rapidly melting Himalayan glaciers means many more problems and far fewer solutions. So it will go for the rest of the region surrounding those mountains, affecting billions of people.

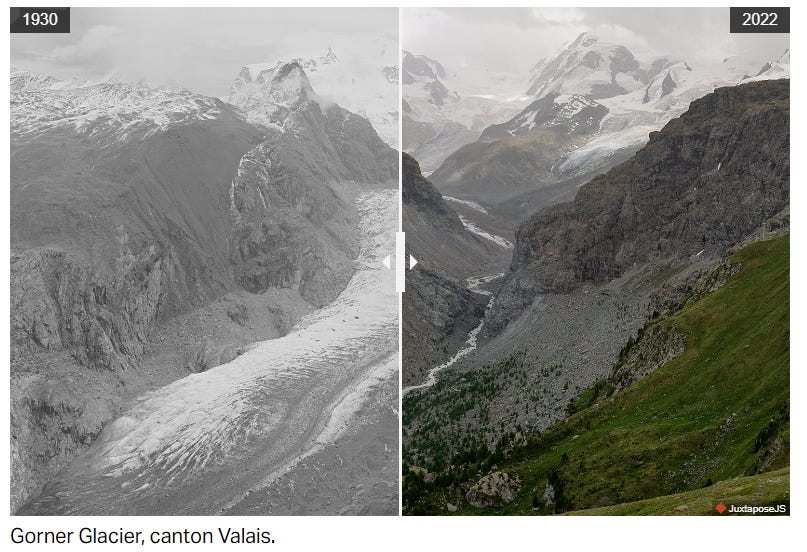

The Alps

Researchers studying alpine ice found an equally daunting forecast there. Using AI modelling coupled with satellite and other inputs, their research indicates about a 34% decrease in ice volume with a reduced coverage area by around 32%. Unfortunately, these are the minimum values produced by their model or, put another way, the best-case scenario. At the worst, alpine glaciers could see an abatement of ice by over 65% between now and 2050. A single year’s data taken between 2022 and 2023 suggests that the worst-case scenario is the more probable result. During that year, a total of 4% glacial mass was lost in the region. In a single year. Glaciologist Matthias Huss said in an interview, “The melting of glaciers last year shattered all records. The melting this year was less shocking for us – and that is worrying.” This dramatic melting tracks with steeply rising temperatures in Switzerland. That country endured an almost 2° Celsius warming over the last century or so, twice the global average. While Switzerland’s water supply will remain sufficient for its relatively small population of 8.5 million (for now at least), those people will instead be at risk of destabilizing glaciers and rivers, which can cause massive, acute flooding, landslides, and other disasters. In addition, major rivers that rely on the ice melt could see water levels fall precipitously. Much of Europe relies on those rivers for interstate commerce.

Source: Swissinfo.ch

The Arctic and Antarctic

In the great north, ice sheets of such massiveness began shrinking in the 1990s and have since tremendously increased the pace. The Greenland Ice Sheet alone contains enough water to raise global seal levels by 7.4 meters (24.28 feet). Between 1992 and 2019, it lost around 3,900 billion tons of ice, which contributed to a rise of nearly 10 mm of sea level. A more recent study suggests that the total ice loss may be 20% higher still. Its current loss estimates would cover an area the size of the US state of Delaware. In total, the annual rate of ice lost in Greenland since 2000 has doubled the rate of loss throughout the entire 20th century.

This level of ice loss, continuing year-to-year, will severely affect local populations of humans and animals. But the consequences are much more far reaching. As noted, the potential impact on global sea level could mean heightened risks for the many shoreline cities and other settlements across the globe. Additionally, a withering ice sheet significantly alters the annual temperature cycle. Already, the Arctic region has warmed four times faster than anywhere else in the world. Increasing temperatures there negatively affects areas further south as they destabilize the jet stream and, therefore, weather patterns throughout the northern hemisphere. It is for this reason that places like the United States and Canada have seen so many more extreme winter events in the past decade or so. The same goes for oceans. A collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), an Atlantic Ocean current that supplies warm air to much of Europe, would drastically alter the climate there. Such a result could lead to major upheavals in farming and water availability. Scientists do not yet know how to predict when that disaster might occur, but they do share consensus on the causation—vast increases of glacial ice melting into north Atlantic waters.

Over the past 30 years, the oldest and thickest portions of the polar ice caps have diminished by 95%. Some estimates expect a 100% loss of summer Arctic Sea ice by 2040, but more likely even earlier. Professor Dirk Notz, of the University of Hamburg, Germany, who studies Arctic Sea ice coverage stated, “Unfortunately it has become too late to save Arctic summer sea ice… This is now the first major component of the Earth system that we are going to lose because of global warming. People didn’t listen to our warnings.”

This has potentially dire consequences for future climatic conditions:

The decline of Arctic and Antarctic ice has many consequences that are already affecting communities across the globe, and will only worsen as the melt rate quickens. The Arctic and Antarctic regions provide a stabilizing effect on the world’s climate. Vast snow and ice covers reflect heat back into space, thereby cooling hotter parts of the globe. As this effect is lessened by diminishing covers, less heat is reflected leading to more intense heatwaves worldwide. The polar jet stream, a high-pressure wind that normally circles the Arctic region, changes its typical track as Arctic temperatures increase. The polar jet stream carries vast amounts of moisture traveling at speeds approaching 300 miles per hour. The path of the jet stream is controlled by the differential of temperatures and atmospheric pressures between the poles and the equator. As the Arctic warms, the differential is reduced causing the jet stream to deviate beyond its usual trajectory. Scientists call this a “Polar Vortex.” As the jet stream creeps away from the poles, warmer air is drawn there while other places experience extreme winters or cold spells.

Conclusion

The political world continues to ignore the swiftly accumulating evidence of a pending apocalypse. Irene Quaile discussed how the recent COP28 event, the UN’s latest climate conference, did no favors for those working to slow or stop these trends. She wrote,

[T]he economic interests of the petrostates prevented anything more than acknowledgement of a vague “transition away” from fossil fuels. I’m afraid I can’t share the widespread (at least some people are doing their damndest to spread it widely) optimism that this was a historic turning point, the beginning of better times. The term “phase-out” had been backed by 130 of the 198 countries negotiating in Dubai but was blocked by fossil fuel countries including Saudi Arabia. In fact, the COP28 President Sultan al Jaber has since clearly stated his intention to keep selling fossil fuels as long as anybody wants to buy them. (Of course there are always two sides to a deal).

Numerous scientists have noted that the 2015 Paris Agreement committed countries to taking measures to keep global temperature rise to “well below 2°C.” Faith in holding to that milestone quickly dissolved when US President Donald Trump unilaterally and foolishly decided to pull out of the agreement a few years later. In a letter signed by over 350 scientists who study ice sheets and their impact on climate, they wrote:

It is time to carve a line in the snow: because of what we have learned about the Cryosphere since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, 1.5°C is not merely preferable to 2°C. It is the only option.

The reason?

Otherwise, world leaders are de facto deciding to burden humanity for centuries to millennia by displacing hundreds of millions of people from flooding coastal settlements; depriving societies of life-giving freshwater resources, disrupting delicately-balanced polar ocean and mountain ecosystems; and forcing future generations to offset long-term permafrost emissions.

They are not the first, only, or last to offer such stark comments. And to date, the predictions made in dire statements such as these have largely been correct, or extraordinarily close (not overhyped as denialists are wont to proclaim). As the scientists rightly concluded in their letter:

The melting point of ice pays no attention to rhetoric, only to our actions.

To read about one absurd attempt to insert conspiracy theories into climate studies, check out this article.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.