Ei Incumbit Probatio Qui

Expounding upon the Issue of Prosecutor Power and Abuse

Visit the new Evidence Files Law and Politics Deep Dive on Medium, or check out the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here. If you enjoy my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thanks!

I started this column because for many years my focus was career-oriented which, while extremely gratifying, did not allow me to spend much time to explore the great many other areas of life that interest me. Initially sharing these thoughts here with a small audience of friends, my plan was simply to write some “explainers” on issues I had spent a lot of time thinking about, or just thought were cool, and to give me room to think about some of them more deeply. If I was lucky, I once mused, publishing these little tidbits might lead to some degree of back-and-forth on the matters on which people share my interests. My primary goal was to lean more toward a clinical explanation of things, and occasionally pepper in my personal views on them in the instances where I held strong beliefs. None of this has changed. What has, however, is the size and diversity of my dedicated readers. Words will not adequately explain my surprise, happiness, and anxiety for such a development. Under the circumstances, it is incumbent upon me to work ever harder to ensure that the words I put to page properly reflect my opinion on the matter and, more importantly, the accuracy of my assertions. Because I am the researcher, writer, and editor, I will from time to time misstep. As dedicated as I am to the factual accuracy of what I write, and to the attention to that in cases where my work might prove educational to some, I am and will remain readily committed to make corrections or clarifications when the situation demands it. This is one such case.

Thank you all so much for reading, commenting, subscribing, sharing, DM-ing me, or in any other way showing your engagement with what I am doing. It means the world to me and is, quite frankly, a ton of fun!

Now, for the business part:

In a previous article titled What to do with Political Criminals, I discussed the indictment of George Santos, a United States Congressman in New York’s 3rd Congressional District. The primary argument was that Santos, through a litany of frauds and deceptions, effectively stole the elected seat, but the recourse for such villainy lies with the political class who have a self-interest in doing nothing to rectify the situation. I asserted that the people of the aggrieved district should have the power to decide the situation, and additionally that prosecuting political figures happens too infrequently often leaving constituents stuck with an apparent criminal, no matter how pernicious the accusations. In making those arguments, and through the use of some poorly chosen generalized language, I seemed to malign an entire profession of prosecutors in a way I had not intended. Ironically, it is a profession with which I am intimately familiar, consisting of some current and former prosecutors for whom I have the most profound respect. While I stand by my general themes, in the pursuit of fairness to those who navigate a very challenging field, allow me to collect the worms released from the can and isolate the ones I actually intended to let out.

While Santos is in fact being prosecuted, I discussed how such prosecutions of political personalities are far too few based on fears that condoning them would give rise to a circus atmosphere of criminal prosecutions for mere political purposes. (A detailed look on this specific assertion is left for another time). Nonetheless, the concern about using prosecutions to influence politics is encapsulated in policy, such as the DOJ’s Principles of Federal Prosecutions, 9-27.260, which states “federal prosecutors and agents may never make a decision regarding an investigation or prosecution, or select the timing of investigative steps or criminal charges, for the purpose of affecting any election, or for the purpose of giving an advantage or disadvantage to any candidate or political party.” Facially, the policy makes sense. It is my view, though, that the application of this policy focuses too heavily on the affirmative decision to prosecute, and thereby ignores the effect a decision not to prosecute actually has on the outcomes of elections.

I noted further that there is some merit to the argument that ‘normalizing’ prosecutions of political people will increase the number of frivolous cases filed with the obvious purpose to influence political outcomes, with no aim at actual justice. In support of this argument, I stated that there are prosecutors who abuse their power, and thus if ‘normalizing’ manifests, prosecutors like these will inevitably jump at the chance to indict political opponents on spurious charges for solely political reasons. I stand by that contention. But, I unfairly generalized the statement. In my supporting statement, I wrote: “District Attorneys frequently abuse their power.” Frequently is a strong term that depends on a great deal more context, which I did not provide. So, I have parsed it more carefully below and edited the original text to reflect a more accurate sentiment. Moreover, I said District Attorneys, rather than prosecutors. I have changed to the latter term to include federal prosecutors in the analysis. In short, I asserted the following positions on this matter, if occasionally inartfully:

Prosecutors have been known to abuse their power;

Few ever face accountability for it;

Which suggests that some of the nation’s prosecutors would be more than happy to pursue criminal charges as political leverage if possible;

Prosecutors should face criminal charges for willful and malicious denial of rights, whether of political defendants or not; and

This may lead to some prosecutors becoming afraid to prosecute real crimes, but that is an acceptable risk.

It was correctly pointed out that my explication suffered from taking an axe to a surgery of a rather complicated problem. I agree. Therefore, I deemed it necessary to better lay out my position.

First, it is important to note that there is some necessity for broad-stroke arguments. That is, many of the underlying facts are not available to the public, for purposeful but not necessarily nefarious reasons. I will identify the caveats of using generalizations where needed.

Second, though I wish it did not need to be said, I will say it anyway: the arguments here do not suggest that the bulk of the profession is corrupt or abusive. Rather, they are focusing specifically on the violators and potential violators. Much like I know through my own experience that police are often maligned for bad conduct committed by a small portion of the profession, such bad behavior is not reflective of the overwhelming majority. Moreover, there is a distinction between elected and line prosecutors. I explore that distinction in relation to elections as remedies. However, unlike many other occupations, bad actors in the criminal justice system commit a disproportionate amount of harm by the nature of their jobs. Even small—nay, miniscule—percentages of bad actors evading punishment is, in my opinion, a serious problem in need of redress. On the arguments:

The Abuse of Power

“Prosecutors have been known to abuse their power.” This is clearly a broad statement in reference to the intentional violations of defendants’ rights or the commencing of a prosecution for reasons other than bringing the defendant to justice. The focus here, and in the previous article, was specifically on prosecutions initiated without any probable cause, or conducted by the willful denial of the defendant’s rights throughout any stage of the proceedings. I stated that “a mere arrest can upend [defendants’] lives in irreparable ways, let alone a frivolous indictment, trial, or worst, a wrongful conviction.” I further noted, “Even in cases where prosecutors patently violate defendants’ rights, often sending them to jail for a lifetime, few ever face accountability, let alone criminal charges.” My original use of the word frequently wreaked of overexpansiveness to describe the universe of prosecutorial abuse, and lacked any requisite context. So, here is that context.

Judge Alex Kozinski of the 9th Circuit minced no words about prosecutorial misconduct in 2013 in US v. Olsen, 737 F. 3d 625:

I wish I could say that the prosecutor's unprofessionalism here is the exception, that his propensity for shortcuts and indifference to his ethical and legal responsibilities is a rare blemish and source of embarrassment to an otherwise diligent and scrupulous corps of attorneys staffing prosecutors' offices across the country. But it wouldn't be true. Brady violations have reached epidemic proportions in recent years, and the federal and state reporters bear testament to this unsettling trend.

Judge Kozinski later wrote, “It’s no answer to say that the exonerees make up only a minuscule portion of those convicted. For every exonerated convict, there may be dozens who are innocent but cannot prove it.” In 1999, the Chicago Tribune found 381 homicide exonerations covering 1963 to 1999, in which prosecutors either “concealed evidence suggesting innocence or presented evidence they knew to be false.” A study covering the years 1970 to 2002, by the Center for Public Integrity, found 2,017 cases of prosecutorial misconduct based on the appellate records (they only examined non-federal cases). The study only counted cases that resulted in overturned convictions or reduction of sentences. Notably, in that study the Center identified 223 prosecutors who had been cited by judges for unfair conduct in two or more cases; only two of them were ever disbarred. The National Registry of Exonerations examined its archive collected from public data sources of exonerations between 1989 and early 2019. It defined exonerations as defendants released after conviction who were later declared factually innocent by a government official or agency with authority to make such a declaration. Of the 2,400 cases in its archive through those dates, it determined that prosecutorial misconduct played a role in 30% of cases. (The organization identified misconduct by other officials, such as police, but that is immaterial here). Obviously, these cases overlap some (from 1989 to 2002), so 2,400 represents the minimum number.

All of these figures cover only known cases where the facts came to light. University of Michigan Law Professor Emeritus Samuel Gross stated, “The great majority of wrongful convictions are never discovered, so the scope of the problem is much greater than these numbers show.” This is because purposeful violations would necessarily be hidden from scrutiny. Moreover, the numbers skew in favor of crimes of greater public interest, such as murders, because there is greater pressure to solve such crimes. Misconduct in lesser crimes, especially those with lighter sentences, is harder to evaluate for a number of reasons. First, it takes an extraordinary amount of time and resources to conduct post-conviction investigations, and the odds of obtaining an exoneration are exceedingly low. For crimes of shorter sentences, though still numbering in years, release often occurs before an investigation could ever conclude, or possibly even begin. Second, many convicted of lesser offenses tend not to have the resources to fund such investigations, and these cases garner less external assistance than cases involving public fanfare. Third, these numbers do not consider plea deals in which similar misconduct may have occurred.

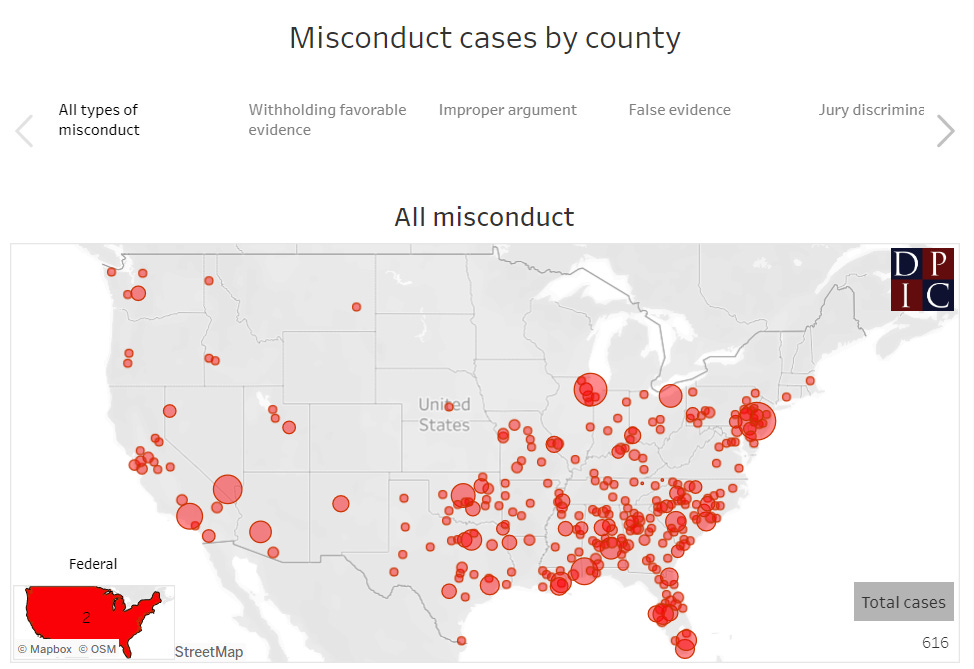

Source: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/policy-issues/prosecutorial-accountability

The overwhelming majority of criminal cases resolve through plea deals, more than 97% at the federal level, and on average about 94% across the states. As Justice Kennedy wrote in Missouri v. Frye, “horse trading [between prosecutor and defense counsel] determines who goes to jail and for how long. That is what plea bargaining is. It is not some adjunct to the criminal justice system; it is the criminal justice system.” Plea bargains remove trial juries from the criminal justice process altogether, and reduce the role of the judge (though judges still have varying levels of involvement depending upon the jurisdiction), leaving much of the discretion to the prosecutor throughout. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, in 2013, at least 61% of the more than 731,000 people in a local-level jail in the United States were there pre-trial, meaning they awaited resolution of their guilt or innocence. Overall jail numbers remained consistent through 2019, and evidence suggests that so, too, did pre-trial numbers. That is, until COVID resulted in a nearly 25% reduction in 2020 and 2021 of the local-jail population. Thus, in an average year (at least up to the COVID era), roughly 450,000 people sat in jail awaiting the chance to plea or go to trial, and about 94% of them did or will plea. The Innocence Project has identified 74 cases in which those who pleaded guilty were exonerated. Those only involved DNA cases. The National Registry of Exonerations reported that 20% of the exonerations it examined since 1989—or 480 cases—consisted of plea deals, though it was unclear on what authorities (prosecutors or police) may have committed violations in those cases (citation above).

In Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 434 US 357, the US Supreme Court majority wrote that “There is no doubt that the breadth of discretion that our country's legal system vests in prosecuting attorneys carries with it the potential for both individual and institutional abuse.” Hayes decided whether a prosecutor acted against due process through vindictiveness in the plea negotiation with the defendant by “carry[ing] out a threat made during plea negotiations to reindict the accused on more serious charges if he does not plead guilty to the offense with which he was originally charged.” It found the prosecutor did not. Justice Blackman, in his dissent, averred, “[W]hen plea negotiations, conducted in the face of the less serious charge under the first indictment, fail, charging by a second indictment a more serious crime for the same conduct creates ‘a strong inference’ of vindictiveness.” This opinion (and its dissent) illuminates the power differential between prosecutor and defendant, which opens the door for potential abuse. Nonetheless, I do not suggest that such “close calls” warrant a punitive response.

Assessing the potential numbers of abuse in the plea negotiation process is especially difficult. First, the details of plea deals are often kept from the public, so uncovering them is exasperatingly difficult. Second, as in any case of official misconduct, incriminating details are almost assuredly kept intentionally hidden, and the unique landscape of the criminal justice system provides enhanced efficacy to do so. Third, absent extraordinary circumstances, plea deals are not as easily or routinely scrutinized as convictions, much of which has to do with the first two reasons. Fourth there is a presumption among many people that affirmative pleas reflect a truthful admission by the defendant and thus receive less attention than possible wrongful convictions.

Prosecutors who purposely commit civil rights violations understandably would take efforts to conceal malfeasance, but defendants who are actually innocent face another hurdle that makes revealing those abusive prosecutors more challenging. Even in cases of appropriate prosecutorial conduct, defendants who assert actual innocence face an uphill climb staking such a claim in the judicial system. As Daniel S. Medwed of the Northeastern University School of Law, put it, “the post-conviction exoneration of an innocent prisoner [might be viewed] as undermining the credibility of the office—and the person—that prosecuted that defendant.” Thus, when a defendant who has pleaded guilty makes a claim of innocence, he or she is in many cases met with resistance even by those who prosecuted fairly. This has an effect on those who have pled guilty not to pursue a claim either at all or to the fullest extent, which also reduces the chance of discovering any instances of malfeasance.

As mentioned, the proven cases of abuse represent a miniscule percentage of the overall number of prosecutions in the United States. Determining an accurate number of indictments and subsequent plea agreements across the USA is very difficult. The Federal Bureau of Investigation maintains a crime database, but it does not mandate reporting. In 2020, only about 62% of law enforcement agencies reported. In that year, reporting agencies made 4,343,654 arrests for a variety of crimes, including misdemeanor and felony, violent and non-violent. Of these, the number that ultimately entered into the prosecution phase are unknown but it appears to range anywhere between 50% and 84%. Assuming the high end, that means 3,648,669 of those may have been indicted or pled out. In terms of potential prosecutor abuse, then, we are talking about a tiny fraction of one percent.

Regardless, the impact on those affected is extraordinary. Thousands of years of unwarranted prison time, among innumerable other harms, from the conduct of this miniscule percentage of bad actors has been the result.

Examples

The Innocence Project has found that only a single prosecutor has ever been jailed specifically for the willful violation of a defendant’s rights, but a reader alerted me to possibly others.1 The one identified by the Innocence Project was prosecutor Ken Anderson, who received a 10-day jail sentence and was disbarred. Michael Morton served 25 years in prison for the murder of his wife, apparently committed by Mark Norwood. Long after his conviction, Morton’s attorneys filed a Public Information Act request, from which they discovered that prosecutor Anderson had withheld information at trial indicating Morton’s innocence. Specifically, Anderson withheld a police report in which the victim’s 3-year-old son described the killer and explicitly stated his father (Morton) was not there at the time of the murder. Witness testimony from neighbors also described the real killer’s vehicle. This, too, was withheld. With this evidence in hand, the Innocence Project moved to test DNA from the crime scene. They found the DNA of the victim and her killer, Mark Norwood, but not Morton’s. Anderson faced criminal contempt and tampering charges for failing to turn over evidence pointing to Morton's innocence, and served a total of 96 hours in jail. Anderson’s punishment, as comparatively miniscule as it was to the punishment of the man he had convicted, represents possibly the only case of a prosecutor spending more than a day in jail for violating a defendant’s rights, in this case costing that defendant a quarter century’s worth of freedom and surely a litany of other harms his incarceration brought upon him.

One reader mentioned Michael Byron Nifong, who prosecuted the infamous Duke lacrosse case back in 2006. The North Carolina bar disciplinary committee determined that Nifong had 1) made public statements materially prejudicing an adjudicative proceeding; 2) engaged in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation; 3) failed to make timely disclosure to the Defense of all evidence or information known to him that tended to negate the guilt of the accused; 4) made false statements of material fact or law to a tribunal (court); 5) made false statements of material fact to opposing counsel; and 6) knowingly made false statements of a material fact in connection with a disciplinary matter. What prompted the disciplinary hearing—and later, his prosecution—were numerous complaints about Nifong’s treatment of the case, including making public statements such as that the defendants were “hooligans.” Eventually, the committee disbarred Nifong, to which he complained in a follow-up letter about the “fundamental unfairness with which this entire procedure has been conducted.” He also served one day in jail for criminal contempt. Later, upon review of some of Nifong’s cases, the court released Darryl Anthony Howard on the basis that Nifong had purposely withheld potentially exculpatory DNA evidence. Howard served over 20 years. Judge Orlando Hudson wrote, “a reasonable juror would find beyond reasonable doubt that here is a reasonable doubt to the guilt of Darryl Howard.” (That’s a bit of a word salad, but the point is salient). Other prosecutors declined to retry Howard. Nifong’s case represents a gray area as to whether he served jail time related to his violation of the defendant’s rights. I could not find the specific facts that formed the basis of the contempt charge. Regardless, counting it here does not push the numbers in any meaningful way.

The so-called “West Memphis Three” each went to prison for charges related to the killing of three young boys. One defendant, Jessie Misskelley, confessed and implicated the other two. Virtually the entire case turned on the confession, as the remaining evidence did not directly implicate any of them, but did supply some corroborating evidence. Many cases rise and fall on confessions corroborated by other evidence. About 14 years after their arrests, DNA evidence surfaced that indicated the defendants were not present at the crime scene, but that the stepfather of one of the victims might have been. In addition, one witness recanted testimony about having seen the defendants in the area of the crime, and evidence also arose suggesting that the jury foreperson on the case was “determined to convict” and may have improperly swayed other jurors. Based on the new DNA evidence, the Arkansas Supreme Court ordered the trial court to consider either conducting a new trial or issuing a full exoneration. Rather than fully investigate these potential improprieties, the prosecutor’s office offered a plea to the murder charges that would release the defendants for time served on the condition that all three defendants accepted the plea and agreed to no further action on the matter. They eventually consented and left prison with a conviction under their belts for murders that the evidence strongly indicated none of them had committed. Had any of them been re-tried, none of them likely would have been convicted; the prosecutors themselves admitted this. One defendant would not have taken the plea but for the fact that one of the other two was sentenced to death in the case. He stated, “This was not justice… However, they’re trying to kill Damien. Sometimes you’ve just got to bite down to save somebody.” In sum, one could argue that prosecutors coerced the three into accepting a plea to a crime that the prosecutors themselves did not believe they could prove, in order to prevent the investigation that might lead either to a full exoneration or to losing a re-trial. No one, as far as I know, investigated whether this was appropriate or an abuse of prosecutorial power.

The Remedies

Federal law prohibits the Deprivation of Rights under the Color of Law, 18 USC § 242. The law includes, “acts not only done by federal, state, or local officials within the bounds or limits of their lawful authority, but also acts done without and beyond the bounds of their lawful authority.” Additionally, “the unlawful acts must be done while such official is purporting or pretending to act in the performance of his/her official duties.” Thus, federal law already prohibits certain kinds of malicious acts by prosecutors, but such prohibitions are practically never enforced.

Prosecutors who have faced criminal liability for willful violations of defendants’ rights are vanishingly rare. In total, to the best of my searching, I could find (arguably) only two, who served a cumulative total of less than 6 days in jail. Note: Other prosecutors have been convicted of crimes, including in some cases abusing their position, but I did not include those because they did not directly involve the violation of a defendant’s rights as they pertain to a prosecution. The conduct of the two, Anderson and Nifong, led to the exonerations of defendants who wrongfully served more than 45 years in prison. It is unclear if the full record of prosecutions of these two individuals has been reviewed. Of the exonerations reported by the National Registry of Exonerations, 93 defendants were sentenced to death. In 283 of the cases mentioned in the report, the defendants served 3,777 cumulative years before release. I could not find the total years served for all 2,400 cases.

Across the 2,400 cases it reviewed, the National Registry of Exonerations found that some form of discipline was imposed on prosecutors in just 4% of them. Of those, it provided the following numbers:

11 disciplined by their office

2 fired

4 resigned (or retired under pressure)

5 demoted or suspended

14 disciplined by their respective bar or court

3 disbarred

2 suspended

4 reprimanded

3 sanctioned by the judge in the case at issue

2 unclear disposition

2 criminally charged (Anderson and Nifong)

6 cumulative days served in jail

both disbarred

The punishment numbers above may represent a slight undercount as it can be difficult to ascertain internal agency disciplinary actions. Punishments by bars or judges, and criminal charges, though, are public records. Therefore, it is safe to say that this largely represents the general disposition of punishment related to these exonerations. Still, using just known numbers, only 27 people who played a provable part in the wrongful imprisonment or other mistreatment of defendants and denigration of the legal system suffered any punishment at all, and just two of them faced criminal liability. This seems wildly imbalanced compared to the thousands of cumulative years people wrongfully spent in prison as a result of their misconduct, including 93 of them who faced execution. There is strong evidence as well that some executions were in fact carried out that involved misconduct in the prosecution. Examples include Carlos DeLuna, Lester Bower, and Brian Terrell.

The known numbers illustrate a woefully inadequate response to prosecutorial misconduct. There is plenty of room for debate as to what the punishments should be, though I unabashedly support criminal sanctions for the most egregious cases. On this, I wrote:

Like for any crime, if a prosecutor’s malicious intent and conduct is provable, then there should be no hesitation to prosecute him or her. As an example, the purposeful withholding of exculpatory evidence, Brady material, should be a criminal offense if the intent is to deny due process rights of a defendant.

I remain committed to this position. In cases where defendants go to jail, face execution, or are in fact executed, the harm is simply too egregious in my view to accept disbarment (or less) as the response. As I noted, this does not require new legislation, it already exists under 18 U.S.C. § 242. The penalties under this law are not overly severe (fines or imprisonment of not more than one year), but convictions under this statute or state statutes would serve two purposes.

The larger of the two is that such convictions would indicate to the public that there is a focused interest in maintaining some level of fairness in the criminal justice system. One study showed that 63% of Americans believe it is equally problematic to wrongfully convict an innocent person or to fail to convict a guilty person. While this contradicts the long held contention that it is “better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer,” it does indicate the expectation of fairness in a criminal resolution. Overall, an even greater percentage found it problematic or highly problematic to wrongfully convict an innocent person. American views on plea bargaining vary quite a bit according to another study, but those disparate opinions align on the notion that plea bargains involving weak evidence, coercion, or the failure to reveal exculpatory evidence are unfair. Maintaining fairness is clearly an essential element to the legitimacy of the US criminal justice system.

The lesser reasoning behind prosecuting prosecutor malfeasance is both deterrence and motivation. Regarding deterrence, the idea is obvious. Putting teeth into the penalty for purposeful misconduct will (hopefully) help deter at least some from engaging in it. But, it may also motivate bar associations and other disciplinary bodies to actually engage in disciplining violators before things go so far. As the National Registry of Exonerations’ report notes, these entities seem to be “deterred by a general reluctance to publicly condemn and punish practitioners in their own profession, or they may lack the resources to investigate and sanction more than a token number of offenders, or they may just not care.” When the alternative could be the embarrassment of a criminal prosecution, disciplinary committees might be more inclined to “care,” and to punish those in their own profession before the matter rises to the need for the intervention of the criminal justice system.

The Courts

For malicious prosecutions—those initiated without probable cause or with a motive other than justice—the courts do provide some protections. Motions to dismiss, or even to sanction, can and do happen, and sometimes successfully. Moreover, defendants who prevail in the courts on the preliminary motions have civil remedies available to them as outlined below. Serially offending prosecutors should still be punished, but disciplinary proceedings would seemingly be sufficient for cases that never reach further steps, as the harm is far less.

For those that do reach further steps, including resolution by plea bargain or conviction, the courts are not an ideal solution. First, appeals take a very long time. It is one reason why so many of the exonerations noted above resulted in huge amounts of cumulative prison time wrongfully served. Second, the defendant’s post-conviction odds are very long for a number of reasons. Prosecutor offices resist post-conviction claims of innocence for a variety of reasons, as noted above. As an example, prosecutors have consented less than 50% of the time to post-conviction DNA testing that led to actual exonerations. Moreover, once convicted, defendants no longer have a presumption of innocence. And even proving one’s innocence does not guarantee a reversal or throwing out of a conviction. In Herrera v. Collins, 506 US 390, the Supreme Court stated rather blithely its view on innocence as a bar to imprisonment or execution.

This proposition [that the defendant is innocent of the crime for which he was convicted] has an elemental appeal, as would the similar proposition that the Constitution prohibits the imprisonment of one who is innocent of the crime for which he was convicted. After all, the central purpose of any system of criminal justice is to convict the guilty and free the innocent… But the evidence upon which petitioner's claim of innocence rests was not produced at his trial, but rather eight years later.

Put simply, after a certain time has passed, absent the discovery of a procedural or constitutional error—which in malfeasance cases are purposely covered up—a defendant often has limited to no recourse with the courts. As James S. Liebman pointed out in a paper in 2002, even DNA exoneration cases often require “relentless lawyers” to procure re-consideration by courts, and typically only then is it “possible to see what actually had happened in the” case. Therefore, without the uniquely compelling nature of DNA evidence indicating actual innocence, such claims rarely succeed if malfeasance is undiscovered and the defendant can identify no other procedural error. “Free-standing” innocence claims, as they are called, struggle against an especially high bar. As the Western District of New York (WDNY) explained in Balkman v. Poole, 725 F. Supp. 2d 370 “traditional remedy for claims of innocence based on new evidence, discovered too late in the day to file a new trial motion, has been executive clemency.” New evidence indicating actual innocence becomes a political rather than judicial issue if it is discovered “too late in the day.” The WDNY went on,

[t]he rule is grounded in the principle that federal habeas courts sit to ensure that individuals are not imprisoned in violation of the Constitution — not to correct errors of fact… The due process clause guarantees only that a trial is procedurally fair, and not that the verdict is factually correct.

In free-standing innocence cases where a defendant does not have the resources or public attention to recruit some tenacious investigators and relentless lawyers to pursue his claims, the chances of prevailing post-conviction whether innocent or not are all but zero.

Civil Suits

The above section addresses prosecutorial misconduct that led to defendants suffering a conviction or accepting a guilty plea. Malicious prosecutions involve those prosecutions which did not go that far, but were initiated without probable cause and for a purpose other than bringing the defendant to justice. Federal law allows a civil remedy for such malicious prosecutions, but the law is fraught with uncertainty. Title 42 USC § 1983, “Civil action for deprivation of rights,” reads:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress, except that in any action brought against a judicial officer for an act or omission taken in such officer’s judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated or declaratory relief was unavailable.

The problem here is that courts have been reluctant to clarify a definition or standard for what “malicious prosecution” means. In Thompson v. Clark, the 2nd Circuit required a showing of “affirmative indications of innocence to establish favorable termination" before reaching the question of whether a prosecution caused a depravation of rights. By this reasoning, the defendant seems to carry the burden of proof of his actual innocence prior to any analysis of whether a prosecution was malicious—regardless of whether charges were dismissed or an acquittal was reached. The 11th Circuit rejected the need to “affirmatively support the plaintiff’s innocence.” In Laskar v. Hurd, the majority wrote, “the favorable-termination element requires only that the criminal proceedings against the plaintiff formally end in a manner not inconsistent with his innocence.” Thus, for the 11th Circuit, an end to the proceedings in almost any form (other than conviction or guilty plea) satisfied the requirement. These two cases generally represented the circuit split. Based on these differing views, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) took a case out of the 2nd Circuit and ultimately reversed the decision. Justice Kavanaugh, writing for the majority, noted “the gravamen of the Fourth Amendment claim for malicious prosecution, as this Court has recognized it, is the wrongful initiation of charges without probable cause.” The SCOTUS opinion further outlined the elements of a malicious prosecution under § 1983:

the suit or proceeding was “instituted without any probable cause”;

the “motive in instituting” the suit “was malicious,” which was often defined in this context as without probable cause and for a purpose other than bringing the defendant to justice; and

the prosecution “terminated in the acquittal or discharge of the accused”

The first two prongs require little clarification. On the third, SCOTUS held that defendants need not assert the reason for the termination of a case against them, nor do they need to affirmatively prove their innocence. Alas, the Court reached that decision only in April 2022. Prior to that, what passed for a malicious prosecution depended upon the jurisdiction in which it would have been alleged to occur. Only time will tell whether this SCOTUS ruling changes the efficacy of claims made under § 1983 going forward.

Such disputing over the language of § 1983 is significant because it suggests that many prior cases that would have satisfied the more important prongs of a malicious prosecution—lacking probable cause and instituted for reasons other than justice—would not have met the third prong—proving one’s innocence. They therefore would never have reached a decision as to whether a prosecution was in fact malicious. As the remedy for victims of malicious prosecutions rests primarily in the civil claim offered by § 1983, the semantics of the third prong effectively disregarded the import of the first two. So, on the whole, this seems to have been a rather limited remedy.

Elections

Elections may be the least reliable remedy for dealing with problematic prosecutors. For federal prosecutors, elections are not an option at all as they are appointed. For District Attorneys, this remedy is not much more effective. Voter turnout in local elections is typically very low, averaging somewhere between 15 and 27% of eligible voters. While a particularly egregious case might raise voter turnout sometimes, absent larger movements this does not seem to have had much effect. Part of the problem may lie in the fact that 38 to 50% of people don’t really know what the District Attorney actually does. Furthermore, as in most races, incumbents in DA races win the vast majority of the time, advantaged by name recognition, funding, the way primaries are conducted, and other factors. In most jurisdictions, prosecutors run unopposed nearly 74% of the time. Three states allow counties to decide whether to elect or appoint prosecutors. [Much of the above data (except as otherwise noted), was taken from the National Study of Prosecutor Elections]. In Oregon, some have accused certain District Attorney’s offices of following a practice that allows them to upend the electoral process. When a DA plans to not run for re-election, s/he allegedly resigns before the next election, which allows the appointment of a deputy almost always from within the office. This deputy then runs as an incumbent which, as noted above, provides an extraordinary advantage for re-election. In 2020, this practice occurred in 11 of 21 DA elections.

The other issue with elections as remedy is that it leaves out punishment for the actual violators. While DAs are and should be responsible for their line prosecutors, misconduct by subordinates does not necessarily reflect the condoning or even knowledge of the elected DA. Moreover, even if that DA leaves office, the line prosecutor still retains the ability to continue the violative conduct either in the same office or somewhere else. This is especially so given the propensity for bar associations to fail to discipline in so many of these cases.

Denouement

This article was meant to clarify the basis of my assertion about the power and abuse of prosecutors in the previous article. It is by no means a comprehensive analysis of the subject. Indeed, hundreds of scholars have penned thousands upon thousands of pages on the subject. I make no claim to be making any serious addition to that canon of scholarship. Nonetheless, some may opt not to read any of those lengthy and often dense articles, so I hope that I have at least represented a summary of the issue fairly here. As always, I encourage any commentary or criticism in the comments section below.

Lastly, on my view on politics in the last article, that too was a broad stroke. But, I stand by it. Are there honorable politicians? Sure. I suspect many of them are at the local levels, and still a few at the higher ones. I heard a person once say something to the effect that once you enter politics, it is near impossible to do the right thing. It was a self-serving statement, to be sure. Yet, it rang with a hard degree of truth. I concede, however, that the Turd Sandwich might have been a bit much!

Thanks to reader Diane LaVallee, who noted my bumbling handling of this issue in the comments on the first piece.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement. Today I work both in the United States and Nepal, and I currently run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas. For detailed analyses on law and politics involving the United States, head over to my Medium page.

For another crime-related article check out below.

It is possible the Innocence Project only included this one because Anderson was actually convicted of tampering with evidence rather than merely criminal contempt, like in the case of Nifong.