Biometrics is a field of computer science that uses features of people—their voice, shape of their face, fingerprints, etc.—to identify them. The principle behind this field is that humans possess many unique traits by which they can be distinguished from any other person. Criminal investigation already uses this idea to help identify suspects. Emerging from Locard’s Exchange Principle, it is summed up by the statement that “it is impossible for a criminal to act without leaving traces of [his] presence.” Edmond Locard used careful analysis of crime scenes to reveal many pieces of evidence that he believed provided a traceable path to a suspect. His efforts led to the resolution of several high-profile criminal cases, and eventually to the widespread use of fingerprint, chemical, DNA and other analyses to identify unique evidentiary elements of crime scenes.

The use of biometrics likewise relies upon the collection of various sources of information to effectively create a unique profile of a person. This allows computers to confirm the identity of said person by comparing it to a previously developed profile. Here, I will examine three specific types of this form of identification: facial, fingerprint and voice recognition.

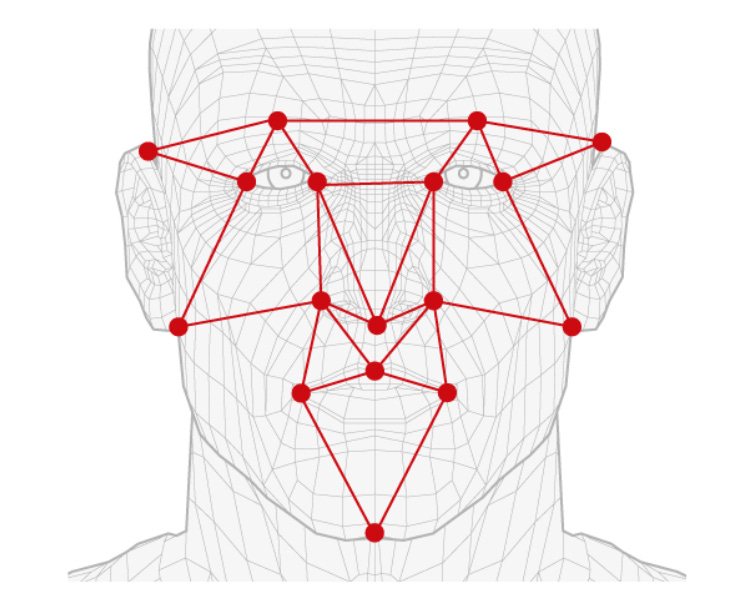

Facial recognition is used in two primary scenarios. One is personalized—such as the kind used to unlock your phone—the other is in the public atmosphere used for a variety of purposes, such as security, marketing, online tracking, and others. At its core, facial recognition relies on geometric characteristics of your face, such as the distance between your eyes, the shape and/or depth of your eye sockets, chin, ears, and mouth. These features are converted into mathematical values that, in sum, create (an allegedly) unique mathematical value for your specific face. (I will discuss the ‘allegedly’ problem in a moment). This value is then stored in a database, or as a single file on your personal device, and compared later to any face that is subsequently analyzed to confirm a match.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/oct/27/live-facial-recognition-police-study-uk

A positive match might be used to unlock a phone, permit access to a secured area, to identify and prohibit access to places for people companies don’t like, to spy on people and sell that information, to incorrectly identify people as criminals, or to secretly spy on people for nefarious reasons not yet identified. You see where I am going with this.

As I discussed in my article on Artificial Intelligence, I am not against employing new technologies out of some Luddite paranoia (notably, facial recognition represents a subset of AI). There are unquestionable benefits to employing facial recognition in certain circumstances. The technology provides convenience for unlocking devices, for easily verifying one’s identity such as with an airline or medical facility, and for customized marketing upon consent.

Unfortunately, also like AI, the rush to capitalize it has led to inarguably immoral applications of the technology in light of its current failures and dearth of regulation on its use. A key deficiency in facial recognition is its considerable inaccuracy among certain demographics. The National Institute of Standards and Technology conducted a study that found that facial recognition systems used by the United States Department of Homeland Security, State Department, and FBI falsely identified Asian and African Americans by a factor of 10 to 100. Its false positive rate for Native Americans was even worse. Unsurprisingly, the study further noted that the algorithms produced by American companies had a substantially higher error rate than those developed by Asian companies when it came to their identification accuracy related to Asian Americans. Authors of another study stated that the problem could not be solved simply by improving analyses of people of a specific race makeup, as such a distinctiveness does not really exist amongst many people. Thus, the technology still requires much improvement.

Another problem with the use of AI, and facial recognition in particular, is the lack of informed consent. Capitalizing such technology without limitation or regulation, that can be weaponized against anyone for any reason, opens the door for substantial abuse. This made the news very recently when some exposed the owner of Madison Square Garden, a widely recognized venue in New York City, of abusing facial recognition. MSG Entertainment allegedly enacted a policy prohibiting the entry into any of its several venues of any lawyer employed by any firm involved in litigation against the company, a number comprising possibly thousands of lawyers. It used facial recognition technology in secret to execute the ban. The company readily admitted to the policy, while asserting that it did not intend to “dissuade attorneys from representing plaintiffs in litigation against us.” CEO James Dolan defended the policy claiming that a litigant would not “welcome the [opposing attorneys] into [his] home.” Maybe Dolan lives in the Garden. Albert Fox Cahn, executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, correctly noted that such use could ban people from grocery stores, pharmacies, and other critical outlets. Lest you think this might only affect lawyers, imagine other professions some companies would certainly love to ban: journalists, movie reviewers, critics generally, police officers, judges, comedians, YouTubers and so many others. While I do believe businesses should have a right to exclude certain individuals for specific reasons, blanket bans such as what MSG Entertainment attempted provide an example of where the slippery slope swiftly coalesces into an avalanche. Banning a known thief or a public figure who espouses violent political views, for example, is a contextually-based, security driven decision as opposed to a blanket prohibitive act intended to dissuade people from engaging in legitimate functions of society. Moreover, it does not require the non-consensual use of hidden technology. Let’s face it, security personnel do not need to rely on facial recognition to identify a regular shoplifter or a loathsome public figure.

Perhaps even more insidious than private sector abuse is that committed by governments. As usual, governments will defend their use of the technology by pointing to their victories when employing them. Unfortunately, these “wins” are far too frequently overshadowed by the large swaths of people who suffer the negative side effects, including substantial civil rights violations. Some members of the US Senate have recognized this and proposed legislation to curtail it in 2020 and 2021. Neither proposal was advanced to a vote despite the obvious privacy, discriminative and accuracy issues with the use of facial recognition technology. Then again, this should surprise no one given many governments’ propensity to use problematic technologies that enable desired outcomes, no matter how illogical or otherwise plagued by evidence-based deficiencies. One need look no further than the polygraph. Despite the fact it is banned for use by prospective private sector employers, and is inadmissible as evidence in most courts, many government agencies in the US still use polygraphs for pre-screening law enforcement jobs or in criminal investigations. Polygraph machines (often referred to very wrongly as “lie detectors”) are little more than movie props backed by no scientific validity whatsoever. Even the American Polygraph Association admits this… tucked in between numerous lines claiming the opposite, which further makes my point about the problem with the uncritical capitalizing of (in this case lousy) technology.

Fingerprint biometrics are built on the principle of the uniqueness of fingerprints across all of humanity, an idea first proposed in the 19th century. This premise is based on the notion that because no two identical fingerprints among two distinct individuals have ever been identified, “we can know without doubt that people’s fingerprints are all different.” While it may be possible to prove this—at least to beyond a reasonable doubt—what may be the first analytical study of this concept was only published one month before this article. So despite the belief in the uniqueness of fingerprints persisting for over a century, only one study so far has attempted to scientifically verify it. Moreover, many studies have otherwise found acute problems in the field of fingerprint analysis, especially among close non-matches. It is, then, somewhat disconcerting that some proprietors of fingerprint biometric programs propound their products, with claims such as that they use “unique physical […] attributes that are individual and not replicable” [emphasis added]. Neither of these ideas, that the attributes are uniquely individual or non-replicable, are necessarily true. On the former claim, the purported uniqueness has extremely limited scientific support. Regarding the latter claim, on replicability, see below. But first, how does it work?

Fingerprint biometrics as security are often touted as more secure because the information is “linked to a specific individual.” The way the program works is to take a digital image of a user’s print, using specific angles of light to highlight the various ridges and valleys. Tiny electric capacitors use electric pulses to measure the discharge created by touching ridges and the absence of discharge by spaces in the fingerprint valleys. (Note this description refers only to “contact” biometric fingerprint reading used by most personal devices). The subsequent pattern created by the various degrees of discharge and light measurements is later used as a basis for comparison. Many devices store the pattern as an algorithm, often encrypted for further protection.

Biometrics companies frequently make the claim that this measure of security is superior to passwords because your security key is part of your body, as opposed to a password someone can guess or steal. It is true that the inherent weakness in passwords is the complacency with which people create, store and use them. I will leave that topic for a more detailed exploration another time. But is it true that fingerprint biometric security is impossible to steal or otherwise compromise? The answer is no. Before I discuss how, note that a compromised password can be fixed by simply changing it. Once a fingerprint is “stolen,” it cannot be changed. This is obvious, so let’s discuss how attackers can conduct such a theft.

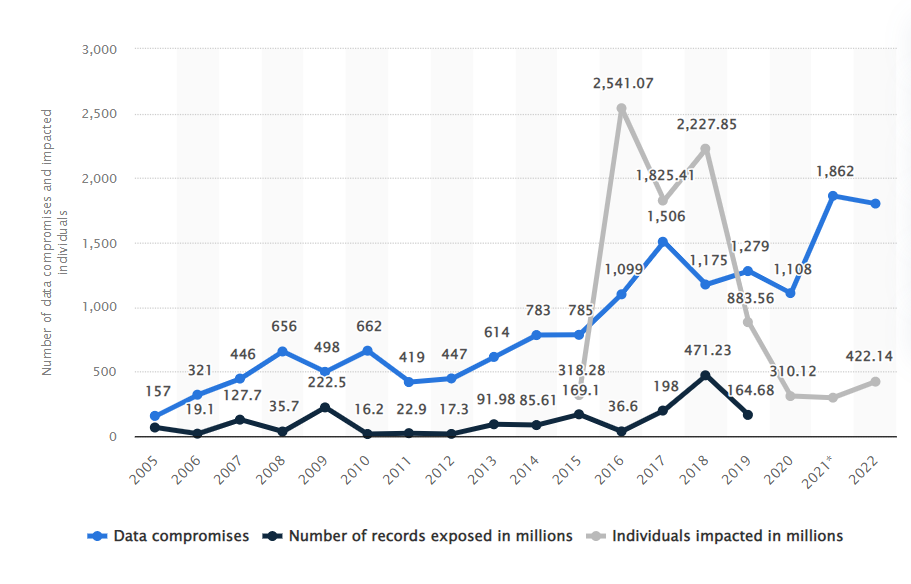

Your biometric traits, unlike passwords, are not secret. You wear them in the open. Fingerprints, specifically, are left everywhere (which is why they are so appetizing to law enforcement as evidence). One study found that using basic fingerprinting film, the type often used by law enforcement and readily available for public purchase, can be used to trick biometric security systems with a nearly 70% success rate. Some systems employ “live” fingerprint scanning, which purportedly can tell the difference between a “live” finger and a copy, though I have not found evidence indicating its efficacy rates. Like all stored information, attackers also target database storage to obtain fingerprint credentials. While most systems seem to encrypt stored data now, these caches remain vulnerable to phishing and other social engineering attacks. This is not speculative, as major hacks have already happened. In 2015, the US Office of Personnel Management, a federal agency entrusted with federal employees’ personal information, was compromised leading to the leak of 5.6 million people’s fingerprints. Researchers also managed to breach a security tool known as Biostar 2 in 2019. They accessed nearly 30 million records, including millions of fingerprints. Had this been an actual attack, companies across the globe, including in Sri Lanka, Belgium and the UAE, would have ceded this treasure trove of data to criminals. As noted, the larger issue here is that once stolen, these kinds of credentials remain compromised forever. And data breaches happen with increasing numbers most years, despite regular advances in security.

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/273550/data-breaches-recorded-in-the-united-states-by-number-of-breaches-and-records-exposed

Similar to fingerprint analysis, voice recognition converts a person’s speech into a mathematical value allegedly based on “unique biological factors,” such as tone, pitch, and cadence, to create a user-specific passkey. Like facial recognition, voice data can also be collected without a person’s consent as it requires only a reasonably high-quality recording. With the ubiquity of excellent recording equipment available on the market today, one need not ponder for long how easy it would be for a company to acquire customer voice recordings. Not to mention, the millions of people that willingly provide their voice to Amazon, Google, and other services. Voice recognition methodology has its own considerable flaws. In 2017, BBC reporter Dan Simmons set up a voice-ID authentication account with HSBC, which had begun using the system the year prior. Simmons’ brother Joe then accessed the account by emulating his brother’s voice, despite claims that the system could discern the difference between identical twins. Just weeks ago, Joseph Cox reported on Vice that he was able to bypass his bank’s voice recognition security to access his own account. He did so by creating recordings of his speech with a limitedly sophisticated AI program, then used those recordings to successfully authenticate his voice with his bank. Companies using voice recognition as a security authenticator point out that virtually no cases of fraud have been identified using such attacks. This sounds, to me, like a car company stating that its newest car with no seat belts has yet to have a fatality, so the car must be safer. With voice recognition, it seems more likely that the crime simply hasn’t caught up to the opportunity. Don’t rest too easily, however. Alon Arvatz, Senior Director of Product Management at IntSights, noted that his company has detected a 43% increase between 2019 and 2021 in hacker traffic regarding “deepfake” attacks—the term used to describe face or voice duplication and manipulation through AI. Previously used primarily for phishing attacks, deepfake tactics are sure to be employed toward bypassing voice authentication security en masse soon, especially as the technology to create deepfakes improves. Despite this, the market for voice recognition technology has seen a growth rate of around 20% per year, and continues growing.

As I discussed previously, there may well be a place to employ some of these technologies in a useful, beneficial way. In some instances, that has already occurred, such as in using fingerprints or face scans to unlock personal devices. But it is clear that letting the market regulate itself—as some are wont to do—is a recipe for disaster. One argument is that government regulation will stifle innovation. This is absurd. Technological innovation will move ahead regardless of some regulation prescribing its use; there is simply too much money in it. Moreover, the ‘stifling’ argument seems impossible to support given that some regulation already exists and yet the technology remains in wide usage and is growing. Illinois, for example, passed the Biometric Information Privacy Act in 2008, which requires consent to collect or disseminate a variety of biometric information. It provides a robust private right of action for violations. Texas passed a similar act in 2009, but requires the government to sue on behalf of violated private citizens. Unfortunately, the corruption-riddled, long-ago-indicted Attorney General of that state only first invoked the law in a case against Facebook (Meta) in 2022. It seems implausible that no violations occurred in the 13 years of the law’s existence prior, suggesting instead that it is just a political tool and not a real law, at least so far. Some states have passed laws prohibiting or limiting the use of facial recognition and other biometric data by governments or law enforcement. Beyond that, few states have imposed any restrictions at all. And none of these regulations seem to have stifled much of anything.

This technology cannot be left to companies to self-regulate, or for government action against clearly egregious conduct to depend on archaic legislation used in novel ways. The MSG Entertainment case is a prime example of the slippery slope that this technology could tumble down without regulation. Failing to prohibit the misuse of such powerful technology is only going to lead to ever-more dangerous violations. Deepfakes could be used to facilitate the false belief in a stolen election, a false call to arms, or some other nefarious tactic. The result could be what some might call a violent insurrection against a major world government. Or maybe just a chaotic Halloween-themed tourist visit… depending on your point of view. But, I digress.

There remains very little regulation imposed on companies regarding their collection, use or dissemination of biometric data (speaking of the United States’ legal systems, anyway). Just two states have somewhat comprehensive legislation, though one seems only inclined to use it to regulate political grudges more than to head off real problems. The relatively light patchwork of remaining legislation does little to stop any abuses beyond a handful of specific circumstances. Nevertheless, the tools to collect bio-data are becoming more and more sophisticated, and the market for the tools to collect such data is growing swiftly. Theft of unchangeable bio-data is rising, contributing to an increase in deepfake production that is becoming vastly more convincing. Tech companies are making billions all the while. There is little incentive to any of the interested parties to self-regulate. The case could not be stronger for governments to intervene on behalf of the people.

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor degree. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, Digital Forensics, and Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I conduct research in all of these, and run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, or Mastodon. Or visit my non-profit’s page here.

update 4/11/2023: On March 30, an appeals court in New York allowed the ban on attorneys suing MSG Entertainment to continue, for the time being at least. Meanwhile, the New York State Attorney General is continuing her investigation into possible civil rights violations. In addition, numerous lawsuits remain in-progress against the company related to this issue. Just 5 days ago, a research paper was published discussing the MSG Entertainment issue in detail, including the potential legal ramifications from that specific case and on biometrics in general. I will explore the arguments in a future post. For now, read their article here.

For more on cybersecurity issues see below.