Visit the new Evidence Files Law and Politics Deep Dive on Medium, or check out the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here. If you enjoy my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thanks!

Note to Readers: The following article discusses child kidnapping and more nefarious crimes that involve child abuse of various natures. Reader discretion is HIGHLY advised.

***

Introduction

What follows is a true crime story that captivated the United States, created a campaign of fear over imaginary ghouls, and ultimately changed the way many people thought about parenting, safety, and society. The narrative below is sourced from primary documents, news reports, books, court cases, online forums, and just about anywhere else people talked about it. All sources are provided as underlined hyperlinks, though typically only upon their first use. What is written herein is based on those various sources, but does not proffer the content as truth. Instead, the goal is to provide the details to the extent possible and let the reader decide what is credible or not. That said, the final section contains my own assessment of the tale weaved throughout.

Just a reminder, the cases discussed involve child abduction, rape, murder, and sexual exploitation, among other crimes. Reader discretion is advised. Grab a coffee and settle in, this is a long one!

***

Johnny Gosch

Johnny Gosch; Source: Des Moines Register

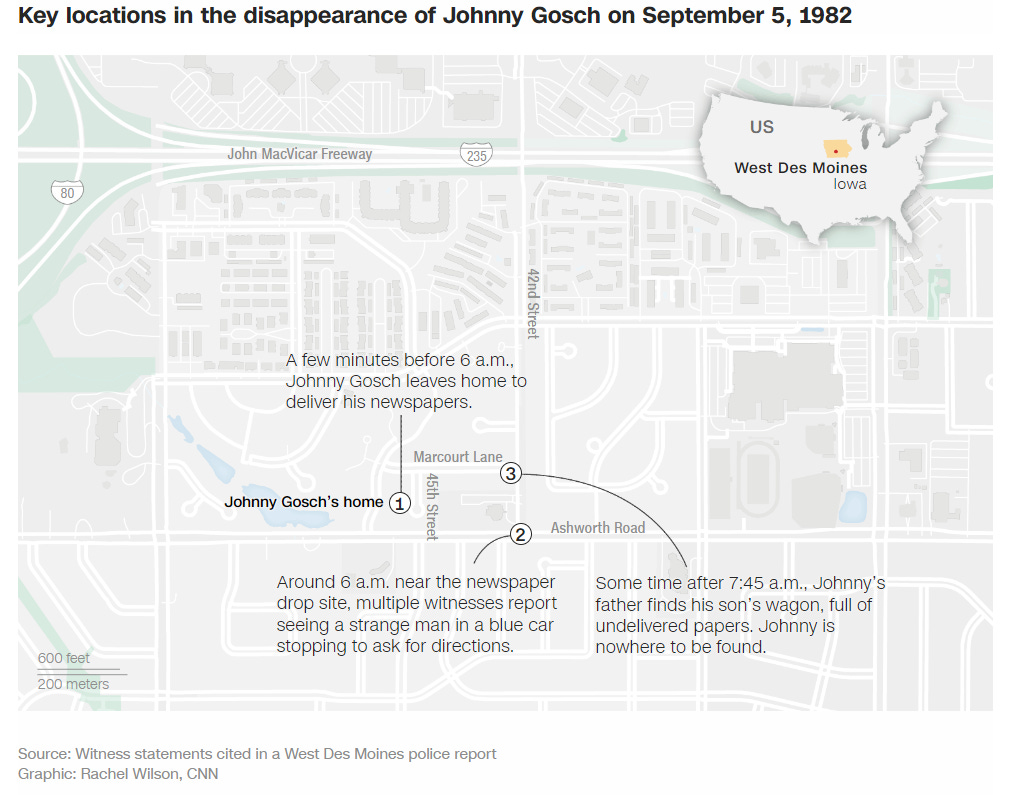

Early in the morning of September 5, 1982, John David Gosch left his home in West Des Moines, Iowa, just as the sun started creeping over the horizon. Twelve-year-old Johnny was a paperboy who delivered to his neighborhood every Sunday. He often woke and recruited his father to assist him with his delivery. On this morning, however, he opted only to bring along the family dog, a miniature dachshund named Gretchen. Gosch delivered papers for the Des Moines Register, so to begin his route he had to stop at a paper-drop not far from his home. There, the company’s distributor would leave behind Johnny’s route’s load in a box for him to pick up. On that fateful day, Johnny arrived ten to fifteen minutes before 6 am according to multiple witnesses who waived hello to him. Johnny was wearing a white sweatshirt with the words “Kim’s Academy” across the back, casual pants, and blue rubber flip-flops while carrying a yellow bag.

Johnny never came home.

Leonard John and Noreen, Johnny’s parents, first learned of a problem when his customers began calling his house looking for their paper. John senior (he seemed to go by his middle name) immediately set out to find him. He quickly located the wagon Johnny used to carry the bulk of his papers only blocks from their home; it still held all the papers. By this time, Johnny had been gone nearly two hours. After searching some more to no avail, he returned home and called the police. The investigation produced variations of what happened, but a general narrative can be pieced together.

While Johnny organized his papers in his wagon, a two-tone blue Ford Fairmont approached the curb. The car stopped and a man inside began speaking with Johnny, apparently asking for directions. John Rossi, whose own kids delivered newspapers, witnessed the exchange as he walked toward the paper drop-off. He was enroute to pick up the batch his own children would deliver that day (distributors would leave papers for multiple routes in a single drop-box). While Rossi collected the papers from the drop-box, he noticed something “strange” about the conversation between Johnny and the unknown man, but continued what he was doing. Still, it stirred some instinct within him enough to take note of the car’s Iowa license plate. He returned to his home without giving it much more thought. When later he learned Johnny had disappeared, he attempted to describe the vehicle to police. Sadly, he could only recall fragments of the plate number.

Source: CNN

One of Johnny’s fellow paperboys corroborated this story, and confirmed the color, make, and model of the car. He further described the man Johnny spoke to as “stocky.” After his conversation with the man, Johnny began walking north, evidently without his wagon or dog. Another paperboy reported that a different man followed Johnny as he walked. It is unclear what this other man looked like or from where he came. A neighbor living north of the paper-drop told police he had heard a car door slam and saw a silver Ford Fairmont with a large black stripe along the bottom speed away in a northbound direction. Johnny’s mother Noreen later said that someone told her that the man in the blue Ford had flashed his dome light three times before driving away from Johnny, perhaps signaling the other man or vehicle. Upon flashing the light, the second man allegedly emerged from some bushes and began following Johnny as he walked northward. No one saw Johnny after that.

Twenty-five to thirty police officers commenced a search of the neighborhood shortly after the Goschs made their report. The next day, the number increased to forty, supplemented by roughly 1,000 volunteers. Searchers scoured local woods, ditches, parks, fields, and even vacant lots and buildings. This massive effort turned up zero clues.

Johnny’s parents initially applauded the diligence of law enforcement, but as no one located any evidence whatsoever, their viewpoint eventually soured. His mother Noreen grew especially impertinent, accusing the police of ‘white-washing’ the case in a phone call she made to the governor’s office. Paul Mokrzycki, writing for the State Historical Society of Iowa in 2015, characterized Noreen’s disposition as possessing a “vigilante ethos” that led to “a spate of public feuds” with law enforcement from shortly after the incident through the 2000s.

Regardless, the case went cold for a long time.

This is an example of what a two-tone Ford Fairmont looks like. This one is a 1981 model and is NOT the suspect vehicle.

The Aftermath

Following the hubbub caused by Johnny’s disappearance, Des Moines Iowa parents and the community entered into a sort of panic mode. Although abduction of children by complete strangers was then, and always has been, exceedingly rare, 1980s media capitalized on the phenomenon in a growing genre of so-called true crime television. Thus, when Noreen Gosch took to the airwaves to implore the alleged kidnappers to return her son, the result in Iowa was poignant.

In the days after the initial search, parents often lined the streets to escort their children to or from school. On the Sunday following Johnny’s disappearance, as paperboys set forth to ply their trade once again, police established checkpoints throughout Johnny’s and surrounding neighborhoods. They even occasionally stopped passing motorists to question them. Management at the Des Moines Register issued emergency whistles to all its paper carriers.

Johnny’s parents joined forces with numerous people and organizations, and created their own called the Johnny Gosch Foundation. They raised funds to pay for private investigators, they arranged meetings of concerned parents, and they contributed to an overall sense of stranger-abduction as a growing—or existing, but concealed—epidemic. Their endeavors, what some might call fearmongering, led to fingerprinting drives of children and started the practice of putting missing children’s pictures on milk cartons, among other things.

Danny Joe Eberle

Danny Joe Eberle; Source: Omaha.com

Thirteen-year-old Danny delivered the Omaha World Herald in Nebraska, about 140 miles from West Des Moines. On a Sunday in September of 1983, he went missing. Herb Hawkins, special agent in charge of the Nebraska-Iowa field office, immediately connected the cases in his mind, later stating:

When I heard [Eberle] was missing, the first thing I thought of was the Gosch case. I thought at that point we could solve the Gosch case at the same time. The circumstances and the modus operandi were so close to the Gosch case. They were paper boys. Their looks were almost identical.

Witnesses reported that on the morning of his disappearance, Danny had been seen speaking to a young man who drove a tan sedan. Although they did not provide any further substantive leads at the time, another witness later called police about a suspicious man. That man, too, drove a tan sedan. The witness recounted the full license plate sequence. Only days after Danny vanished, a search party found his body with multiple stab wounds. He was bound with rope tied in peculiar knots.

Police traced the vehicle to John Joubert, a 20-year-old man from Omaha. When they apprehended him, Joubert had a knife and rope stowed in a duffel bag; the rope directly matched pieces found with Danny’s body. The rope itself was of an unusual make, crafted by a single factory in East Asia, allowing police to discern its manufacturer, purchaser, and to positively link the two. They also discovered that this same type had been used in another unsolved murder in Nebraska of a 12-year-old boy. Further investigation revealed Maine police sought Joubert in connection with the murder of an 11-year-old boy there. Joubert was ultimately convicted and executed for his crimes in 1996.

While the case of Danny Eberle fueled conspiracy theories and fear, the FBI found no connection between his and Johnny’s. Joubert, investigators determined, had acted alone, and no evidence placed him anywhere near Gosch. In fact, they eventually learned that Joubert had not been in the Midwest at all around the time of Gosch’s ostensible abduction. Following the two incidents, however, news stories frequently broke of young boys fleeing from suspicious people, particularly ones characterized as “weird” or “strange.” Fear had overtaken the entire region.

Eugene Martin

Eugene Martin; Source: Iowa Cold Cases

On August 12, 1984, Eugene Martin left his home at 5 am wearing blue jeans, a red shirt, and gray hoodie. Like Johnny, he headed to a paper drop-off as he, too, delivered papers for the Des Moines Register. His paper pick-up point was just 12 miles from Johnny’s. Also like Johnny, Eugene usually had help—his older stepbrother. On that day, however, he decided to go it alone so he could pocket the full amount of money. He intended to spend it at the Iowa State Fair later that day.

At an intersection near to the paper drop-off, Eugene was seen speaking to a “clean-cut white male” in his 30s sometime between 5:00 and 6:05 am. Witnesses who saw the conversation reported it occurring at different times, hence the range. Most of them told police that the two looked like father and son, so they did not pay much attention. While the exact time of the conversation varied among the witnesses, it seemed it occurred while Eugene was preparing his papers for delivery. Eugene always folded them separately into his bag for easy retrieval as he walked his route.

Whatever the exact time of the conversation, a manager of the Register found Eugene’s bag with ten papers folded inside lying on the ground by the box around 6:15 am. It seems he had returned to the drop-box when Eugene’s customers called to advise they had not received their papers yet. Rather than report this rather odd discovery to the police, the manager went and delivered the papers himself. Thus, Eugene was not reported missing for nearly two and a half hours, at 8:40 am.

Upon Eugene’s disappearance, the FBI announced that his and Johnny’s case had a “definite connection.” They issued a nationwide “be-on-the-lookout” for a 5-foot-9 inch clean-shaven white male with a medium build, between 30 and 40 years old. A decade later, FBI Agent in Charge Herb Hawkins, said that based on some “useful information” obtained from witnesses at the time that they believed:

the person is an introvert, a loner who may or may not be extra guilt-ridden on what he does but will not turn himself in.

Detective James Rowley of the Des Moines police did not share the FBI’s belief that Eugene’s and Johnny’s cases were connected. In 2009, he told the Des Moines Register, “Why the two-year gap? [Serial killers and kidnappers have a] growing appetite [for crime]. Where was he before ’82? Where was he between ’82 and ’84, and where was he after ’84?”

Connected or not, Rowley determined that the kidnapper had somehow talked Eugene into leaving his route. After that, no one saw Eugene again. His case also went cold.

Marc James Warren Allen

Marc James Warren Allen; Source: Iowa Cold Cases

Roughly two years following Eugene’s disappearance, another Des Moines area boy vanished. On March 29, 1986, Marc said goodbye to his mother Nancy as he left to visit a friend’s house down the street. Marc had been a difficult child, and in the years before his disappearance he had been living with his father in Minnesota. He returned to live with his mother in January of 1985 because Marc wanted to be close to his younger brother and older sister who still resided with their mother. On the evening of March 29, the siblings were preparing a pizza for dinner as Marc was leaving. As he stepped out the door, he told his mother “Save me some pizza, Mom. I’ll be hungry when I get home.” She watched him walk until he reached a bush line where he turned and waived. That was the last time she saw him.

The next morning, Easter Sunday, Marc was nowhere around the house. His mother thought maybe he had stayed the night over at his friend’s house or had left early for his grandmother’s house to collect his Easter candy. Neither proved to be the case. In fact, no one had seen him at all—not even the friend to whom Marc went to visit the night before.

Police have not identified a positive link between Marc’s case and that of Johnny or Eugene, but they have not ruled it out either. Nonetheless, in all three cases, no body has been found and no other evidence has turned up since their disappearances. At least according to everyone but Johnny’s mother Noreen. But more on that below.

Religious Cults

Just weeks after Johnny’s disappearance, Noreen had floated the idea to the media that a religious cult abducted her son. The group she initially targeted, called The Way International, supposedly contacted Johnny in August causing a change in his personality. It seemed members of that group had visited houses in the neighborhood to extend their message, one of which was the Gosch house. Later, in 1984, at a hearing before the United States Senate, Noreen accused the North American Man-Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) of being responsible for Johnny’s disappearance. She stated:

Information . . . has surfaced during the investigation [into Johnny’s presumed abduction] to indicate organized pedophilia operations in this country in which our son perhaps is a part of it.

At the time, the FBI began focusing its attention on NAMBLA in a number of missing children cases, though not necessarily precipitated solely or even at all by Noreen’s testimony. The agency never divulged whether it believed NAMBLA had anything to do with Johnny’s disappearance. Still, she zeroed in on it as vindication of her suspicions, frequently repeating the claim that pedophiles had taken her son, although no evidence supported this proposition at that point.

A writer to the editorial page of the Omaha Herald restated Noreen’s arguments, elucidating fears of “white slavery” and other threats against children, and that:

Omaha kids stopped feeling like kids that year [when Johnny went missing]. We felt like prey. Scared all the time. Every car—or God forbid, van—that drove by us too slowly. . . . Our nightly prayers filled up with new anxieties. Please God, protect me from kidnappers. And rapists. And people who put AIDS-infected needles in phone booth change slots. And if I am kidnapped and raised in another state, please help me to remember my real name and phone number, so that someday, after the kidnappers start to trust me, I can call 911.

In a letter to then-Iowa Governor Terry Branstad, several mothers posited the following:

My daughter Allyson and I attended a meeting last night on child safety. The speaker was Noreen Gosch. What she said angered and shocked me. Our children are a very special gift and should be protected [through] greater involvement and interest by State and Federal employees. [Another added how] fortunate [she] was . . . to hear Mrs. Norene [sic] Gosch speak in [her] community about the statistics on this problem [of child abduction and molestation]. God is speaking through her to alert us of the growing operation of molesters and abductors.

Noreen’s message about child sex trafficking groups hunting children captured collective interest, particularly in the Midwest. Eugene’s disappearance, which occurred just days after Noreen testified before the Senate, only bolstered the public outcry. In a news feature on ABC World News Tonight, an Iowa paperboy visible only from behind and shrouded in a drawn hood, told the reporter, “Oh, I don’t know what I’d do if somebody kidnapped me because it’d be kinda scary ‘cause they might kill me or take me away and then brainwash me or something. I’d never see my family again.” A person named Irish Cowell from Sioux City emphasized the sex trafficking theory as the source of the disappearances, stating:

We [as a society] are obsessed with sex! Nothing pinpoints its vulgarities and sadist pleasure more than the porno material. Our children have become victims of untold horrors for the explicit purpose of bringing joy to those who receive their monthly publication.

Carolyn Keown from Des Moines added:

As a parent, I raise my 15-year-old to believe that the world is a good and just place. Now it makes you wonder if it is still good and safe. You could never have told me when I was 15 years old that people are like they are now. So many just don’t care for one another. There are so many wicked, perverted people. So many religious cults. So much hatred for each other. So much pornography involving children.

President Ronald Reagan himself called the Des Moines Register editor to offer his sympathies and advise that the federal government would “get right on it.” He later espoused a policy of “tough on crime,” citing the Iowa cases explicitly.

Noreen Continues the Campaign Against Traffickers and Cults

Noreen experienced several other alleged incidents over the years that only caused her to dig in further on the theory that her son now belonged to some kind of sex cult. Just six months after his disappearance, a woman in Oklahoma purportedly encountered a boy out of breath on a street corner asking for help. He blurted that his name was John David Gosch just as two men grabbed him and dragged him away. It is unclear if she ever reported this to police, but when she later saw a story about Johnny on the news, she called a private investigator working for the Gosch family. The PI later affirmed that he was “convinced it positively was Johnny” who the woman met, and he handed the information over to the FBI. They never disclosed what, if anything, they did with the information.

On February 22, 1984, Noreen answered a phone call just after midnight in which a male who sounded like Johnny said, “Mom?” Someone on the other end immediately hung up the phone. She received two more back-to-back calls, both ostensibly from the same person, but little more was said. Noreen claimed Johnny sounded “drugged” or “hurt.” Police told her they could not trace the calls.

About a month after the phone calls, Guy Genovese, a sheriff’s investigator in Nueces County, Texas, told the media, “I believe the boy [Johnny] is alive and I believe he can be found, but I’m not saying when or anything like this.” His remarks came on the heels of at least 12 reported sightings of Johnny in the area between January and July of 1983. Genovese further noted, “We've got some better leads now than we did last summer. He (Gosch) was supposedly seen with two guys. He's taller now and his hair is darker brown.” Hawkins from the FBI, however, told media that the reports from Texas had “not brought the FBI closer to cracking the case.” Nothing ever developed from these leads.

In 1985, a man from Michigan wrote Noreen saying that his motorcycle club was responsible for abducting the boy, planning to use him to demand a ransom. No one ever produced any evidence supporting this claim.

In 1989 or 90, a man named Paul Bonacci advised his attorney that as a child he was kidnapped by sex traffickers. His abductors later forced him to snatch Johnny for the same purpose. Bonacci was close in age to Johnny, so his captors figured when “kids your own age are talking to you and stuff you normally aren’t frightened by them.” Based on this, Bonacci relayed that his role was to “lure [Johnny] or get him close enough to the car where we could get him in.” A man named Tony accompanied him and pushed Johnny into the car while Bonacci talked to him. He said that he used “a chloroform-soaked rag over [Johnny’s] face” to incapacitate him and then he and Tony drove him out of town.

Bonacci described what happened next:

That night at first Emilio and this couple other guys went into town to drink. And they left me, Mike and Johnny in a room that had no windows on it. That they had locked from the outside of the room and stuff. They lock us all three in this room. And that night when they got back they ordered me and Mike to do some things with, sexual things with Johnny. And they filmed it so that they could sell the film or whatever they were going to do with it.

And then a couple of months later I got a chance to take a trip out to Colorado. And that’s where I seen Johnny Gosch the second time. And at that point he was staying with a guy that I only knew as The Colonel. And it was a kind of a ranch house but it was out, had a raised floor, underneath there was a space that had been dug out. And that’s where they kept some of the kids at and stuff when they caused trouble or were bad.

Note that Bonacci also told this story in a court hearing years later, which included certain identical verbiage.

From there, Bonacci claimed “Johnny was sold to a pedophile in Colorado” and that “he was on the road with Johnny and others for about seven years and [Bonacci] last saw him In Colorado in 1989.” Bonacci added that Johnny was later shipped to a country “in the area of the Netherlands… where this type of activity is legal.” Noreen later reported that when she finally met him, Bonacci told her that Johnny was renamed Mark, has black hair and is 6-foot-4.

She believed Bonacci’s story because he stated things “he could know only from talking with her son.” For example, he knew about a dirt bike Johnny bought, and that sometimes he went to yoga classes, neither of which were reported in the media. He also accurately described Johnny’s birthmark and several scars. Furthermore, Noreen said Bonacci had “multiple personality disorder,” and while police evidently advised her that only one of these supposed personalities admitted to all this, psychiatrists assured her that “people with multiple personalities typically don't lie.” Nebraska State Senator Loran Schmitt who investigated the Franklin scandal—described below—wrote in an affidavit in 1991 that “this Senator now believes that Paul Bonacci did tell the truth to the Franklin committee and the Committee Investigator” about the details related to Johnny.

West Des Moines detective Gary Scott said at the time that “We already know what [Bonacci] is saying. I have a good relationship with the [Gosch] family. I'm not going to get into an arguing match with her, but we have reservations as to what we’re hearing from Bonacci.”

When he was giving Noreen his information, Bonacci was serving jail time for sexually assaulting a child. His assertions about his role in the Gosch affair received far greater attention. But first…

Johnny’s Mother Describes an Unusual Visit

In March 1997, fifteen years after Johnny’s disappearance, Noreen Gosch received a knock at her door. It was 2:30 am, and standing there was a late 20s male who claimed to be her son. Another man stood there with him. Noreen claims that the younger man proved he was her son by showing a birthmark on his chest. The three of them sat in her living room for an hour-long discussion. She described her now 27-year-old son’s demeanor as follows:

He was with another man, but I have no idea who the person was. Johnny would look over to the other person for approval to speak. He didn’t say where he is living or where he was going.

She asserts Johnny told her he had been abducted for a sex trafficking ring and that she should not inform police of his visit as it would endanger their (his and her) lives. She offered to call her private investigator instead, but Johnny begged her not to do that either. Johnny relayed what happened at the abduction, stating simply that he had been “pulled off the sidewalk into a car, where he lost consciousness.” He later awoke in a basement, bound and gagged, with Bonacci by his side. Bonacci told him “just do what they tell you and it will be all right.”

Noreen also says that Johnny advised her that he was on the run from his captors. He debated coming to see her, but decided to anyway to ask her to help arrest and bring his kidnappers to justice so he could safely come out of hiding. It is unclear how she would do this while simultaneously not reporting his visit to anyone. Both police and Johnny’s father—who no longer lived with Noreen as they had divorced some four years earlier—questioned her account.

Later that year, in September, John Gosch seemingly changed his mind when Noreen showed him an envelope of photos purportedly left on her doorstep. The images depicted several boys all tied up, and one looked a lot like their son. Police examined the photos and determined that they were part of a hoax perpetuated in Florida some time earlier. Noreen did not accept this explanation, but Florida Investigator Nelson Zalva who investigated the case nevertheless confirmed it. He had spoken to the boys in the photo directly. Moreover, Noreen never produced any definitive evidence of Johnny’s visit—not to the police or to her husband. Of note, she first publicly told this story under oath in a civil proceeding launched by Paul Bonacci against Lawrence King in a deposition in 1999.

Paul Bonacci

In 1993, the Nebraska Court of Appeals heard a case involving Alisha J. Owen, who was convicted on 8 counts of perjury related to an investigation into the Franklin Community Credit Union. Lawrence King, who Bonacci sued six years later, was once the manager of the credit union. Relevant here, Owen and Bonacci, along with two other individuals named Troy Boner and James ‘Danny’ King, “claimed they had been sexually molested by adults involved in an ongoing scheme of child sexual exploitation.” The adult perpetrators purportedly all had a connection to the credit union and to Lawrence King (Lawrence does not appear to be related to Danny King).

A grand jury convened in 1990 to investigate the allegations, before whom Owen testified and whose testimony served as the basis for her perjury convictions. Boner and Danny recanted statements they had previously given to the police, telling the grand jury that they concocted the whole molestation story because they believed it would “eventually lead to lucrative book, television, and movie contracts.” The appellate court further pointed out that the grand jury found that all four of them—Boner, Danny, Owen, and Bonacci—lacked credibility, and likely would have reached that conclusion regardless of whether Boner and Danny had recanted. Owen and Bonacci nevertheless both stuck to their statements leading to prosecutors filing perjury charges against each of them. The appellate court upheld the perjury convictions against Owen citing ample evidence to support them and finding no significant errors by the trial court. Prosecutors dropped the perjury charges against Bonacci because he was already serving time for molesting a child.

During the same year that the Nebraska Court of Appeals upheld Owen’s convictions, a documentary filmmaker interviewed many victims involved in the supposed sex conspiracy seeking to determine the veracity of their claims that 1) they were flown around the US to be abused by high-ranking officials; 2) the FBI ‘covered up’ the crimes; and 3) that Lawrence King ran an underground club in Omaha, Nebraska, through which he, along with well-known politicians, businessmen, and media moguls forced children as young as eight years old to have sex with them.

Interviewees made many extraordinary claims, such as accusing the government of using scare tactics—including murder—to force their silence on the matter. The documentary further claimed that King selected residents of a nearby home for orphaned kids called Boys Town to populate his scheme’s ranks of children to abuse. Paul Bonacci proclaimed he was one of these boys. Notably, the grand jury investigating the case concluded that the abuse stories related to the Boys Town home originated from a vindictive employee terminated for unknown reasons some time before, and thereby had no truth to them.

The documentary also asserted that any investigator or agency who looked into the matter was immediately told to stand down by “anonymous” callers backed by powerful people. One investigator from Senator Schmitt’s office, Gary Caradori, did not back down. He later died in a midflight aircraft breakup that also killed his son. His partner in the investigation, Karen Ormiston, stated in the documentary that she believed the FBI had something to do with the crash. She added, “the effect of Gary's crash on the investigation, I think it put an end to anybody else coming forward with information.”

Boner, who recanted his testimony to police when seated before the grand jury, said in the documentary that he did so because of pressure from the FBI. He also claimed he did not plan to testify against Owen at her perjury trial, but changed his mind when his brother died from an “inexplicable gun accident.” Investigators of that incident reported that Boner’s brother was engaged in a drug-fueled game of Russian Roulette. Boner nonetheless believed that “They killed him somehow, professionally made something happen to shut me up. The purpose of Shawn's death was to instill fear, and it worked.” In 2003, according to the film, Boner went to a New Mexico hospital “screaming that someone was after him” while bleeding from the mouth. Nurses found him dead in his room the next morning. Many online stories assert that his death resulted from a drug overdose, but official records seem unavailable.

Owen served about 4 years for her conviction and King received 15 years for various charges related to fraud and embezzlement, serving roughly 10 of them.

Despite initially facing charges for lying to the grand jury, Bonacci later sued King for his role in promulgating his ritualistic abuse by King and a larger nationwide pedophile ring comprised of powerful political figures. In a hearing related to the case on February 5, 1999, Noreen Gosch testified. It was in this hearing that she first regaled the tale of Johnny showing up at her house. She also said:

We have investigated, we have talked to so far 35 victims of this said organization that took my son and is responsible for what happened to Paul [Bonacci], and they can verify everything that has happened.

What this story involves is an elaborate function, I will say, that was an offshoot of a government program. The MK-Ultra program was developed in the 1950s by the CIA. It was used to help spy on other countries during the Cold War because they felt that the other countries were spying on us…

Well, then there was a man by the name of Michael Aquino. He was in the military. He had top Pentagon clearances. He was a pedophile. He was a Satanist. He’s founded the Temple of Set. And he was a close friend of Anton LaVey. The two of them were very active in ritualistic sexual abuse. And they deferred funding from this government program to use [in] this experimentation on children.

Where they deliberately split off the personalities of these children into multiples, so that when they’re questioned or put under oath or questioned under lie detector, that unless the operator knows how to question a multiple-personality disorder, they turn up with no evidence.

They used these kids to sexually compromise politicians or anyone else they wish to have control of. This sounds so far out and so bizarre I had trouble accepting it in the beginning myself until I was presented with the data. We have the proof. In black and white.

The civil judge, Warren K. Urbom, presiding over Bonacci’s case awarded him a default judgment of $1 million against King because King never responded to the summons or otherwise participated in the case. In a response in 1990 to the Washington Post about King’s purported involvement in sex-abuse or trafficking, he simply called the allegations “garbage.”

On the merits of the case, Judge Urbom wrote the following:

Between December 1980 and 1988, the complaint alleges, the defendant King continually subjected the plaintiff to repeated sexual assaults, false imprisonments, infliction of extreme emotional distress, organized and directed satanic rituals, forced the plaintiff to ‘scavenge’ for children to be a part of the defendant King’s sexual abuse and pornography ring, forced the plaintiff to engage in numerous sexual contacts with the defendant King and others and participate in deviate sexual games and masochistic orgies with other minor children.

But, because King never showed up, the judge clarified that these were mere unproven allegations and that he had “reasons to question the credibility of [Bonacci’s] testimony.” In affidavits of other witnesses, one stated that King ordered him to “take pictures of Paul, various other children or various other people… in compromising positions, you know, sexual type things.” He could not produce any photos, however, because he had allegedly given them to investigator Caradori who died in the plane crash. A CNN reporter filed information requests for the photos with the FBI and Oregon State Police, but they refused to confirm whether they had them or would not release them due to an ongoing investigation.

Noreen’s Proof?

Whatever the ‘proof’ she had then or now, she has not to date revealed it in any convincing way. But, as she would contend, it is not the lack of evidence but the reception it got when she provided it to various law enforcement agencies over the years. For example, she has long held that the West Des Moines police department regularly dismissed her and her evidence. This no doubt emerged as a result of her frequent, and loud, criticisms of their efforts to find her son. Chief Orval Cooney once retorted to her remarks to the media:

I really don’t give a damn what Noreen Gosch has to say. I really don’t give a damn what she thinks. I’m interested in the boy [Johnny] and what we can do to find him. I’m kind of sick of her.

Noreen later fired back that Cooney was a “known drunk” and incompetent. Her vitriol was not unfounded. About a year before she said that, the Des Moines Tribune published a story based on interviews with 14 of the 20 patrol officers in the department that accused Cooney of having:

beaten a handcuffed prisoner, compromised a burglary investigation implicating one of his sons and threatened and harassed his own officers. They say they have smelled alcohol on his breath when he was on the street at night checking up on them and that they’ve seen beer cans in the vehicle he uses.

A subsequent investigation resulted in several whistleblowers losing their job while Cooney remained chief, though the firings reportedly resulted from some of their own malfeasance and not retribution. Noreen also announced that during the search for Johnny, Cooney had told some volunteers to “go home” because “the kid is probably just a damn runaway.” Indeed, the police did not immediately classify the case as a kidnapping even after they received the witness statements described above.

The FBI also seemed stubbornly uninterested in the case, in Noreen’s view. She believes this is because the conspiracy embroiling her son was/is:

all so big, so powerful, so pervasive, that the authorities would never solve it, would never arrest anyone, because, as [she] had come to believe, this is America, where some people are sacrificed because others are above the law.

Back in 2003, she and her attorney planned to sue former Chief Cooney as a means to force the revelation of what the West Des Moines police had on Johnny’s case. They wrote a complaint alleging misconduct by the chief, but he died suddenly of a heart attack at 69-years-old. As the lawsuit was filed against him individually, it was dismissed.

Thomas Lake, a reporter with CNN, interviewed Tom Boyd, another West Des Moines detective who worked the Gosch case for 20 years and largely kept things cordial with Noreen. Boyd said he did not want to call Noreen a liar, but that the whole thing is “weird” and he just doesn’t know what to believe. The situation was made no easier by the fact that every time he sat down with her, “topics just start branching out everywhere.” Moreover, her failure to report certain events, like Johnny’s alleged visit, meant that he could not follow up on them. “There was always this open gray area where I can’t say it didn't happen and I can’t say it did… That’s how a lot of this investigation has been for me over the years,” he stated.

Many of the figures in this sordid narrative are dead now, some perhaps suspiciously like investigator Caradori, and others less so, like Chief Cooney (whose apparent alcoholism probably killed him) or Troy Boner (who almost assuredly died from a drug overdose). Others are simply too self-interested to be believable, like Alisha Owen or Lawrence King.

So, what about Paul Bonacci?

Police never interviewed him, which of course raised suspicions. Detective Boyd seemed regretful that they had not, though he noted that other officers determined that Bonacci could not have participated in Gosch’s kidnapping based on information they learned from family members. Unfortunately, police have not disclosed the substance of that information other than it showed that Bonacci was not in Des Moines at the time of Johnny’s abduction.

Still, CNN reporter Thomas Lake was not satisfied with that result. He drove to the last known address for Bonacci in Omaha. He managed to locate Bonacci, now 56-years-old, near the address. Bonacci reluctantly agreed to speak only briefly, so Lake asked whether he believed Johnny did in fact visit his mother back in 1997. Bonacci replied yes, he knows it because Johnny himself admitted it to him. Lake then queried whether Johnny is alive now. Bonacci answered that he is and has his own family.

In a subsequent interview that Lake procured by showing up at the house once again (Bonacci never answered Lake’s texts or calls after their first discussion), the latter asked if Bonacci had any documents or photographs to prove his story. Bonacci maintained that everything he has said over the years remains his version of the story today. Nevertheless, any physical proof he might have once possessed was “destroyed in the flood here,” referring to a flood that damaged his house in 2019. He further stated that he last saw Johnny in 2018, but he lives in hiding for fear of being killed if he comes out publicly.

Lake then headed to Noreen’s home, where he relayed what he heard from Bonacci. Noreen and her current husband George unequivocally accepted Bonacci’s story as true, positing that Johnny probably was forced to do illegal things himself while in captivity. Staying hidden thus makes sense, they contended. Yet, they also believe that Johnny watches over them and “keeps tabs on things.” Bonacci, they informed Lake, has told them so. Furthermore, Bonacci and Johnny keep in touch.

Noreen called Johnny and Bonacci “blood brothers” while George said, I will “give you 2-to-1 odds, that Johnny knows you [Lake] were at Paul’s house by now.” The two professed that they have spoken to more than 100 people who suffered similar fates to Johnny and Bonacci, including some who visited them at their home back in West Des Moines (by the time of this interview, they had since moved to a houseboat). Six of the victims they spoke to allegedly saw Johnny and knew details about him not available in the public domain, according to Noreen.

SPOILERS: An Objective Assessment

There simply is not enough evidence to summarily accept or reject any theory propounded in this case. At the least, the evidence suggests that Johnny and Eugene were abducted, and possibly in related incidents. The information on Marc’s case is quite scant, making such assertions far more tenuous. Given his history, he might indeed have just been a runaway.

That said, while Noreen’s obsession is understandable, if not wholly reasonable, the rabbit holes down which she has gone seem to be just that—rabbit holes of conspiracy and intrigue where little exists. Sadly, when all things remain on the table, the most likely answer will almost always be the simplest one—that Johnny and Eugene were abducted by a lone pervert or sociopath who killed them and disposed of their bodies adequately to defy their discovery. In America, this happens often enough, so much so that it has kept innumerable YouTube channels in business for decades.

My intuition on the case can be resolved to the following:

Law Enforcement - In the 1980s, missing person cases simply did not get the same level of attention or diligence that they tend to now. An apparently unenthusiastic investigation does not, itself, provide any particular indication of some vast conspiratorial coverup. Here, the police chief of the West Des Moines Department seemed riddled with his own serious flaws—alcoholism, racism, corruption, and brutality—such that he was not one to be told how to do his job even if he was objectively bad at it. Noreen’s public rantings against law enforcement certainly did not help matters and were, in my estimation, premature. I know from my own experience the apathy that can develop among investigators from an especially vocal and disruptive family member of a victim. Not to mention, even without that frustration, such continuous commentary creates a distraction in the form of false leads or witnesses who become uncooperative who otherwise would not have been.

Agencies refusing to release records under the auspices of ‘ongoing investigations’ also does not suggest a conspiracy. Unfortunately, this is par for the course in the United States where no matter the utility or lack of harm to a case, law enforcement is reluctant to ever release information on unsolved cases, even when those cases become quite old or stale. Such is the culture. There are good reasons for this as well as bad.

Gary Caradori - What might appear at first blush to be the strongest piece of evidence pointing to a broader conspiracy is the circumstance surrounding the death of Investigator Caradori. He is the one who died returning from Chicago while flying his personal airplane that subsequently broke up midflight. I do not, however, believe this to be anything more than an unfortunately timed accident. Here is why.

First, as the many scandals in the past decade indicate, massive conspiracies simply do not remain secret for long. Those that seemingly do probably are not conspiracies at all, but they contain a sufficient number of peculiarities that purveyors profit from continuous retellings of them (often with added twists from time to time). Case in point: the assassination of JFK.

The act of sabotaging a plane at Midway Airfield in Chicago is an acutely risky one that would no doubt leave a great many witnesses. Even if those witnesses did not have definitive proof, some would likely still testify to odd things they saw. This is especially so in a case involving the death of a Senate investigator. Even without witnesses, the number of investigative agencies that would and did become involved following the incident would make a cover-up exceedingly challenging and fraught with peril, even for the FBI. There is no ‘big brother’ capable of containing the most rash or righteous law enforcers.

Second, the proclaimed ‘weirdness’ associated with the crash incident shows most commentators’ ignorance about aircraft crash causation. The NTSB crash report reveals a number of indicators suggesting this crash occurred because of pilot error for the all-too-routine reasons: pilot fatigue, weather, and experience. Caradori was piloting the aircraft alone, accompanied by only his young son. He had just 1,208 hours of flight time—not wholly inexperienced, but also not a veteran pilot.

The flight departed at 1:51 am after Caradori and his son visited multiple tourist sites and took in a baseball game, meaning fatigue likely played a role. The plane was a single-engine Piper Saratoga, a small, fixed-wing aircraft especially vulnerable to bad weather. Caradori was flying under instrument flight rules (IFR) and the weather along the entire route was not good. While neither the cloud ceiling nor the altitude of the plane are given in the final report, visibility was probably at or near zero. Indeed, responders at the crash site declined the use of any aerial assistance because of the severity of the weather at the time.

Multiple witnesses on the ground reported to police that they heard what sounded like an engine wind up and down before the sound of the crash. They did not see any midair fire or explosion. Moments prior to the accident, Caradori radioed air traffic control (ATC) stating that his compass was ‘swinging,’ and then ATC lost all contact. The use of the term ‘swinging’ here probably referred to magnetic deviation. This phenomenon occurs when localized magnetism affects the readings on a magnetic compass, which was what Caradori’s plane used. With the prevalence of thunderstorms in the area, it is probable Caradori’s compass was acting up due to the heightened magnetic charge of the fuselage or adjacent instruments. Moreover, the lack of recently identified maintenance in the NTSB report hints at the possibility that Caradori’s plane contained no compensation methods for this occurrence.

Immediately after his communication about the compass, Caradori’s plane made several abrupt altitudinal changes. Given the apparent failure of his compass and possibly other instruments, the bad weather and poor visibility, his failure to further communicate, and his wild flight path, Caradori likely suffered from spatial disorientation, where one cannot discern up from down. As his instruments went berserk, and without any external visual cues, he radically maneuvered the aircraft probably confused about which way was up, eventually descending while mistakenly believing he was climbing. In short, he panicked. The Piper Saratoga has a flight ceiling of 15,000 feet and a max speed of 191 mph. If he inadvertently commanded a dive and drastically exceeded this speed, breakup of the plane was inevitable if the dive started at a high enough altitude. Pieces of the wreckage, particularly the state of the stabilator, support this theory. So, too, do the reports of witnesses who heard the engine wind up and down—probably the doppler effect caused by the plane rapidly changing altitude.

The death of Caradori and his son was a grave tragedy. Although the timing of it surely raises eyebrows, an objective look at the evidence all but puts conspiracy theories to bed. Yes, it remains possible that someone tampered with the plane with the intent to bring it down. Caradori had expressed such concerns before the flight. These fears may also have triggered his panic. Ultimately, the odds of a conspiracy wherein someone tampered with the aircraft are vanishingly small compared to the almost certain culprit: the man simply made a series of mistakes that ended lethally.

Paul Bonacci - Paul Bonacci’s role in this is a bit harder to unweave because he is eminently uncreditable. Still, the evidence points to two primary possibilities. One is that he is nothing more than a troubled person or conman who spent decades taking advantage of a grief-stricken woman for his own benefit. The second is that the police completely dropped the ball, missing the facts indicating Bonacci is the perpetrator.

On the former point, Bonacci never once produced any verifiable evidence of any of his claims. The closest he came was in the instances where he allegedly told Noreen things only someone who met or knew Johnny could know. The problem here, however, is that an astute conman can tease out those details from the person with whom he speaks, then provide them as if he himself knew them first. This is the hallmark of con-artists, used in all sorts of frauds such as phishing, psychic readings, and romance scams. Because Noreen wanted to believe Bonacci’s various stories, she would be easily manipulated into giving away information without her realizing it. Bonacci also did tell Noreen things he could know from the media that maybe she simply did not notice, or assumed Bonacci himself had not seen. An example of this is his description of Johnny’s new name and look. He told Noreen in 1990 about Johnny’s current height and dark colored hair, but this had been reported to the media by Texas law enforcement some six or seven years earlier. Either Noreen did not know, or she perhaps presumed Bonacci did not.

Furthermore, when Bonacci regaled others with details of his supposed involvement, the stories did not make sense. For example, his recounting of the abduction of Johnny itself did not comport with witness statements and contained what one might call a movie trope.

Recall his first statement back in 1989:

Bonacci was similar in age to Johnny, so he figured when “kids your own age are talking to you and stuff you normally aren’t frightened by them.” Based on this, he added that his role was to “lure [Johnny] or get him close enough to the car where we could get him in.” A man named Tony accompanied him and pushed Johnny into the car while Bonacci talked to him. He said that he used “a chloroform-soaked rag over [Johnny’s] face” and then he and Tony drove him out of town.

Bonacci used the term “we” even though no witness identified two suspects at or in the car while Johnny had his conversation. Moreover, other witnesses reported that Johnny walked at least a block away from the point of this conversation. If Bonacci meant he was at the second car, the silver Ford, it seems odd that “getting Johnny into the car” required a second conversation. Remember that by the time Johnny got to the location of the second car, he had abandoned his dog, wagon, and carrier bag according to the witnesses and evidence. Further, in a later confession (given below), Bonacci said he was in a blue car, while the second was reportedly silver, suggesting his initial statement referred to the first point of contact with Johnny that did not conclude with him entering the vehicle.

Next, Bonacci said that he used a “chloroform-soaked rag” to incapacitate Johnny. Enter the movie trope. The myth of the chloroform-soaked rag has been propagated in books and movies forever, but it was never true. As anesthesiologist Dr Sathya Kumar notes, “You can’t anaesthetise a patient so easily. The victim will never faint in an instant. It takes a good two to five minutes for the patient to slip into unconsciousness, and even that only if an unusually high dosage is administered.” Chemist Ben Pilgrim adds:

[Chloroform] was replaced [as a sedative drug in medicinal procedures] because it was dangerous. Dangerous for a couple of reasons; one is actually you just breath too much of the gas in your lungs and this fills up your lungs and stops your lungs getting enough oxygen and so you just die from not having enough oxygen. But also, if you start fiddling around with the nervous system, then it can also cause people's hearts to fail because hearts rely on electrical impulses to work and if you mess around with that, you can die of a heart attack.

J. P. Payne, an anesthesiologist who regularly testifies in criminal cases in which the defendant is accused of using the substance, found only two cases since 1850 where chloroform was actually used—and even then, unsuccessfully both times. From this, he paraphrased a conclusion published in the Lancet medical journal over a century ago, “If [only criminals] would uncover the secret of instantaneous insensibility which could be used for the benefit of society as a whole! Needless to say the secret has yet to be revealed.”

Finally, Bonacci announced that all the physical evidence he once held had been destroyed in a flood at his home in 2019. This seems a rather convenient set of circumstances, especially since he had decades before to produce it. Furthermore, one has to question how he collected and carried this ‘evidence’ through decades of bouncing from one flop house to another as a trafficked child and young adult.

John DeCamp - Paul Bonacci’s lawyer John DeCamp penned an entire book on his assessment of, not Johnny specifically, but the alleged sex trafficking ring in which his client purported to be involved. But like Noreen, the book provides a great deal of conjecture without much in the way of substantive fact. For example, his chapter on Caradori’s death does not address any reasonable inferences about the cause of the plane crash, despite the book’s fourth edition being released about fifteen years later when the NTSB and other reports were available. DeCamp also recounts statements Bonacci made to a Nebraska investigator that themselves did not align with those of crime scene witnesses and other evidence. For instance, Bonacci describes the car used in the abduction as a “Chevy,” when multiple witnesses labelled it a Ford.

Bonacci’s story differed even more wildly, including from his own versions offered elsewhere:

Paul Bonacci: Yeah. I was sitting in the back seat with Mike.

Investigator: You're both sitting there? Were you hidden in the back seat or were you just sitting up normal?

PB: Down low, kind of sitting on the floor. And then Emilio, I guess, I don't know what he did, but he, Mike told me, he says, when the car slows down, he says, when you feel the brakes jerk, he says, I'll grab him and you just hold him down. And so it happened quick. It's like we went up, I felt the brakes jerk, and I saw the door fly open and I saw Mike jump out and the next thing I know there was somebody, you know, he grabbed the boy and he'd thrown him in and my job, you know we were supposed to do is just hold him down and gag his mouth so he couldn't yell or nothing. And then after we had, just, like two seconds, just spun off, tore off, got out of there.

In this recounting, Bonacci does not speak to Johnny at all, despite previously attesting that his similar age to Johnny provided the impetus for his involvement. Moreover, according to the witnesses, this story would have required him to be in the silver Ford, but he earlier said he was in a blue one (well, a blue Chevy, according to him).

As with Noreen, DeCamp seems to have fallen victim to his own delusions. He simply wants there to be a vast conspiracy for him to crack that simply isn’t there. His reliance on witnesses who are proven liars and his failure to address actual evidence that contradicts his desired narrative damages his own credibility, especially as an attorney. But his dissembling probably does not arise from a nefarious motive. DeCamp seems to truly believe what he has propounded. The reason why conspiracy theorists find such financial success in purveying stories that the uninvested find to be ludicrous is because for the people who want to believe them, no amount of contradictory evidence will change their minds.

Did Bonacci kill Johnny? Although he was quite young himself at the time of Johnny’s disappearance, there is a considerable amount of evidence that would support further investigation into this possibility. He did, after all, admit to participating in the abduction. Even if his facts did not align with the witness statements and other evidence, that could be the result of an intention to misdirect investigators. It also could be the result of his own misremembering his made-up stories. Pedophiles, serial killers, and kidnappers often feel an emotional surge when committing their crimes. If Bonacci was simply caught up in the feeling of the act and lying about it later, he certainly could have forgotten details when retelling the story numerous times.

Bonacci purportedly told Noreen things about Johnny that a stranger could not know. If true, the reason could be that Bonacci did know them because he himself had abducted and killed the boy. It would also explain his continued involvement in the case. A few serial killers and rapists have been known to inject themselves in the investigation of their crimes as a subtle means to obstruct it. Perhaps more likely, as the FBI noted early on, maybe Bonacci felt intense guilt for what he did and sought to somehow appease Noreen (or himself). Don’t forget that Bonacci served time for sexually assaulting a child. Recidivism of such criminals is among the highest of all crime types. Maybe murder was not his intention, but happened by mistake or necessity to prevent capture.

Little direct evidence exists pointing to Bonacci as the perpetrator. But it is also true that the police never seemed to consider him a suspect. This was based at least in part on their determination that Bonacci was not even in the area at the time of Gosch’s disappearance. Police never revealed how they came to that conclusion, but detective Boyd did not seem fully convinced by it. Furthermore, police did not even interview him. Perhaps whoever is working the case now should reconsider doing so.

Noreen Herself - Make no mistake, the Gosch family endured one of the worst experiences a family can and John Sr. and Noreen deserve our sympathy. That said, Noreen herself cannot be taken at her word because of her own understandable need to maintain that it is more likely her son is alive but trapped in a conspiracy, rather than long-dead at the hands of a random psycho. She seems a victim of a self-created psychologically internal Stockholm Syndrome, made worse by charlatans preying upon her emotions by engaging in cruel hoaxes. In her refusal to accept that Johnny was probably abducted and quickly killed, she has weaved a tale of conspiracies and super-villains to fill the deep, dark hole in her heart. No compassionate person can fault her for the potent emotions that led her there, but compassion does not require accord.

Her decades-long campaign has not produced anything particularly fruitful in terms of evidence. Statements she has made to the press, before the senate, or in court remain uncorroborated, irreconcilable, or altogether absurd. Invoking ideas such as that the CIA was involved only makes her sound like a madwoman. Dropping such grandiose assertions demands equally extraordinary evidence, of which she has produced nothing beyond that which is vaguely circumstantial at best. And that is being generous.

Coda

One can simultaneously dismiss one conspiracy theory while acknowledging that others exist. The Gosch case and its associated moving parts illustrate a wide variety of nefarious activity that happened in Nebraska and Iowa. Amateur sleuthing driven by powerful self-interested motives can, however, lead to one finding connections where they do not exist; or at least they do not exist as the pillars of some grander plot. The characters in this saga all possess underlying self-interests, some sinister and others comprehendible yet sad. Every one of them, though, have allowed these motives to take them to fantastical places that for a while captured the public imagination. Sadly, that is all this overarching narrative seems to be—imagination powered by two very tragic, but simple, crimes.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement. Today I work both in the United States and Nepal, and I currently run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas. In addition, I teach Tibetan history and culture, and courses on the environmental issues of the Himalayas both in Nepal and on the Tibetan plateau. For detailed analyses on law and politics involving the United States, head over to my Medium page.

Just crazy and twists at every corner to wind up a cats-game.