The Tarai is Baking

How our Artificially Warming Planet Poses Huge Risks to Southern Nepal

Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Nepal’s Tarai region is baking, literally. Here in Kathmandu, the temperature eclipsed its highest point so far this year, at an exhausting 33.3°C (92° for the Fahrenheit folks). During the day, absent any breeze, that temperature with its high humidity is stifling. And yet, it pales in comparison to the heat in the Tarai Region. Over the past week, the Kanyam Tea Estate, Dumkauli, Okhaldhunga, and Dharan Bazar weather stations have recorded temperatures breaking 50-year-old records on at least five of the days of the first week of June. On June 7, for example, Dharan Bazar reached 39.3°C (102.74°F). Thirteen other weather stations in the region recorded record-breaking temperatures for June as well. The highest of these, Bhairahawa, recorded a whopping 41.2°C (106°F).

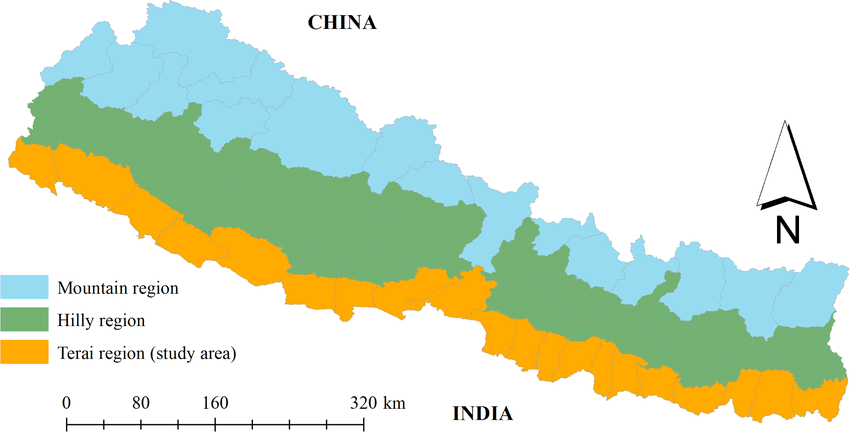

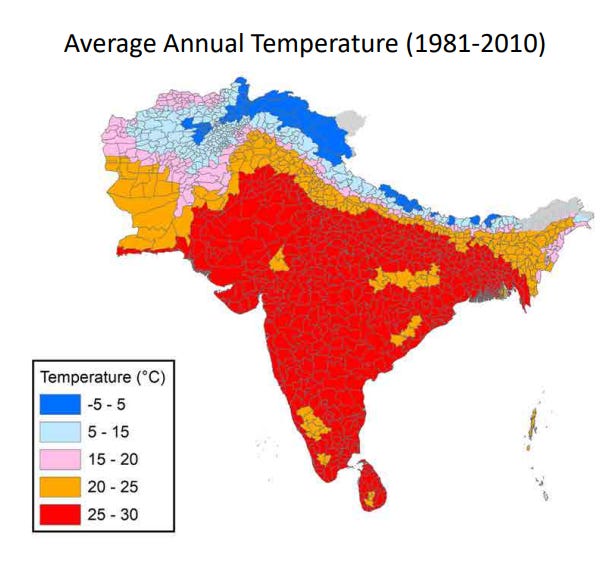

The Tarai (sometimes spelled Terai) comprises the area of northern India and southern Nepal, running roughly parallel to the Himalayan Mountain range. Consisting of the lowest elevations of Nepal, and about 23% of its total land area, the region’s name derives from the Urdu word (ترائی) meaning ‘lands along a watershed’, while in Hindi (तराई) it means ‘lowland’ and in Nepali (तराइ), ‘plain area’.

Used under Creative Commons license, 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

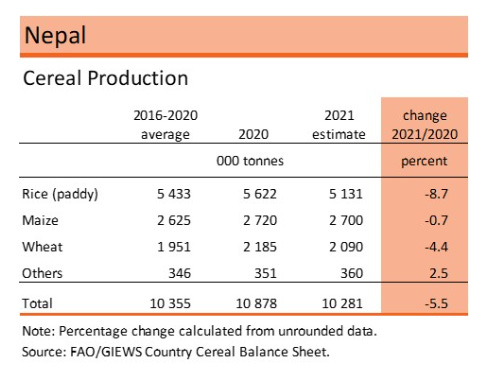

Several large rivers crisscross the area, including the Yamuna, Ganges, Karnali, and Koshi, enabling agriculture as the prime economic driver. About half of Nepal’s population lives in the Tarai. Rising population has contributed to urban sprawl in the region, resulting in a more than 400% increase of land turned to urban development use between 1989 and 2016. Nearly 93% of this development consumed agricultural land. This is problematic considering the Tarai’s place as the “bread-basket” of Nepal, producing 56% of the nation’s cereal, and 70% of rice and wheat. As agricultural output declines, the nation increasingly imports more food to sustain its population. This has shifted agriculture’s contribution to Nepal’s GDP from 33.18% to just 23.13%. Indeed, Nepal imported 39% more food items in 2020-2021 than the previous year, and its rice imports alone since 2000 have risen from around 8,000 tons per year to 1.2 million.

Agricultural production provides employment for 66% of Nepal’s population. Decreased production raises concerns about income and livelihoods, and the specter of food insecurity—currently a problem for an estimated 2.8 million people in Nepal. Additionally, the more the country spends on imports, the more this influences inflation. From 2022 into 2023, food price inflation climbed to 7.5%. There is some projected growth in the agricultural sector for 2023, which could help mitigate this, but only about 2.6%.

Urban development’s overtaking of agricultural lands makes flooding a significant threat. With Nepal’s mountains feeding rivers at lower elevations, floods occur just about every year. Since 2016, however, flooding in Nepal has increased and led to significantly more loss of life and damage. From 2005 to 2015, all but two major natural disasters in Nepal directly involved flooding (the exceptions being the Jure landslide in 2014 and the Gorkha earthquake in 2015). Since then, flooding and landslides (often caused by flooding) have been the biggest calamities in Nepal in terms of lives and dollars. Flooding directly affects agriculture, too, as it destroys crops and inhibits the use of land. Recognizing this, the Nepal government instituted the Priority River Basins Flood Risk Management Project in coordination with the Asian Development Bank. The hope of the project is to reduce damage to farmland to prevent the destruction of crops and reduce the necessity of imports.

Increasing temperatures has had a significant effect on farming in the Tarai in several important ways. First, as average temperatures rise, the way rain falls has changed. From 1986 to 2006, Nepal saw an overall increase of 163 mm per year of precipitation, with all of it occurring during the monsoon season, while rates have been decreasing in the winter months. Since 1990, incidents of rainfall typically comprise much heavier rains followed by longer, drier periods between. Heavier rainfalls tend to runoff, leading to lower levels of soil saturation. Limited saturation in summer and decreased precipitation in the winter months has exacerbated drought conditions, and contributed to more incidents of fires. Drier surface conditions create an environment for fires to easily start and spread, while less water makes extinguishing fires harder. As fires ravage agricultural areas, themselves diminished in size by urban sprawl, the sustainability of the soil lessens for some time, thereby reducing output. These combined factors may require a significant shift in the choice of crops in order to adapt to changing circumstances.

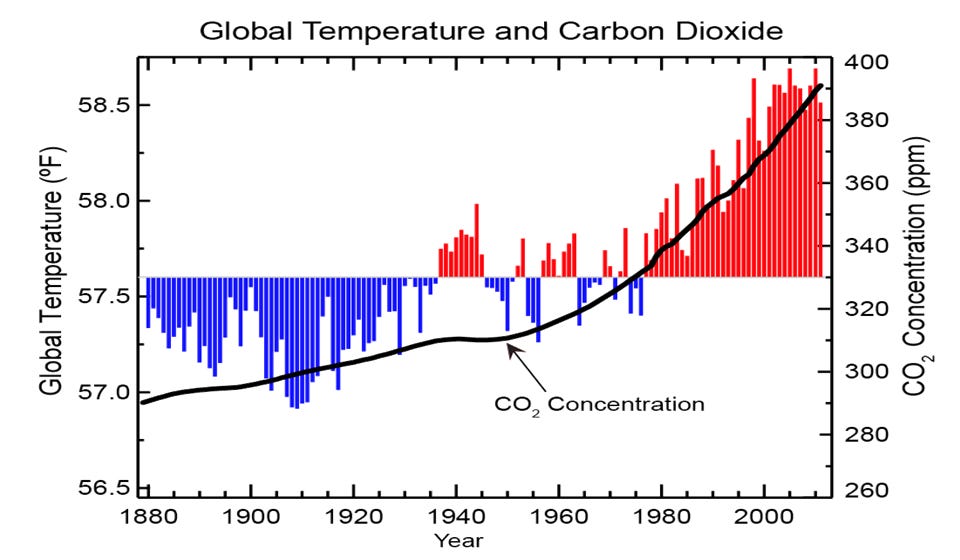

Similarly to adapting to soil conditions resultant from drought and wildfire, changing temperatures and atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels will impact the timetable and crop choice for planting and harvesting. Elevated levels of CO2 in the atmosphere lead to crop outputs with reduced protein and micronutrient content. High heat intensity, even in short spurts, causes heat stress on plants which reduces production rates as well as the nutritional content. As such, equal-sized plots of land will produce an overall lower nutritional yield as temperatures and atmospheric CO2 saturation continue to soar. While diminished nutritional value forces consumers to buy more, it also negatively affects soil aeration and sustainability. The shortened life-cycle of crops under the pressure of higher temperatures decreases their ability to regenerate nutrients necessary for future growth in subsequent cultivation periods. This will also affect production as farmers will be forced to cycle land plots more frequently and for longer times to ensure their future viability, just as demand for more crops will rise.

Source: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

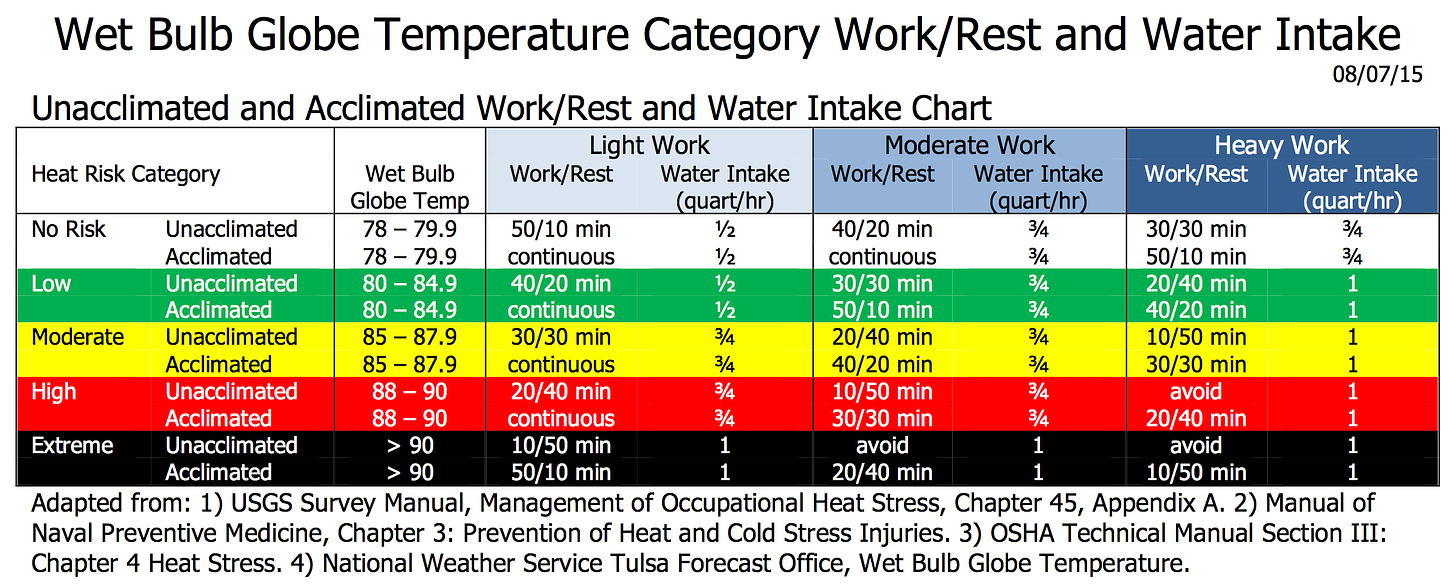

Perhaps the most immediate effect of the baking of the Tarai region, however, is the simple survivability of living in such temperatures. A key indicator is what experts call the “wet-bulb temperature.” This describes the “lowest temperature to which an object can cool down when moisture evaporates from it.” Higher temperatures reduce the human body’s ability to cool by evaporation (namely, when sweating). Colin Raymond of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory states that the highest wet-bulb temperature at which humans can survive for longer than six hours is 35°C (95°F). As the wet-bulb temperature depends partly upon humidity levels, the higher the humidity, the lower the actual temperature humans can withstand. Daniel J. Vecellio found through empirical testing that the tolerable wet-bulb temperature might be less than 35°C even for young, healthy people, and is lower still for older people or those suffering various medical conditions.

Source: Oklahoma Mesonet Agriculture Program

Changing climatic conditions have increased the probability of heat waves occurring by 30 times. Last year, India and Pakistan—both of which directly abut Nepal’s Tarai area—reached the hottest temperatures since people began keeping records there, 122 years ago. Some places have hit the 50°C (122°F) mark. Scientists expect this trend to continue in many parts of the world, but especially in South Asia. Studies have shown that even nights will offer less respite than in the past. Models indicate the highest numbers of nighttime heat waves will happen in the area of northeast India in particular, which includes the Tarai region. Worse still, the projected number of nighttime heatwaves will probably exceed daytime heatwaves, despite daytime temperatures still regularly reaching dangerous heights.

Source: World Bank

In a region dominated by agricultural and physical labor, the higher prevalence of extreme temperatures will lead to higher numbers of heat-related deaths or illnesses. Avoiding work at peak temperature times does not provide enough solace from the effects of such extreme heat. And, while I could not find exact numbers, it seems likely that a relatively small percentage of people in the Tarai have access to air conditioning. This is based on the fact that just 12% of India’s population has air conditioning. Even for the minority that might have it, increased stress on power grids worldwide often leads to losses of electricity during the harshest periods of heatwaves. With the limited availability of air conditioning, the overwhelming majority of Tarai residents will face regular bouts of perilous heat without any remedy, including nighttime cool-down periods.

Climate scientists have for some time set a 1.5°C increase in global average temperatures as the tipping point. The tipping point is when certain conditions become irreversible and have the potential to lead to cascading disastrous effects. In 2022, the global surface temperature average was 0.86°C (1.55°F) warmer than the 20th century average. The TEN warmest years in the historical record have all happened since 2010. Furthermore, a recent study estimates that Earth will probably surpass the 1.5°C threshold by 2050, though others offer a much more ominous prognosis. Climate warming compounds the requisite conditions for the formulation of disasters like flooding, drought, and wildfire, so crossing the threshold will lead to a rapidly increasing number and severity of such events. Add to that the diminished water supplies caused by accelerated ice melt in the Himalayas, and the Tarai region along with much of South Asia is facing a truly calamitous second half of the 21st century.

While the climate change problem requires a global political will for action that has so far proved woefully inadequate, many organizations and individuals are doing what they can to mitigate the effects at the local level. I have devoted a whole series toward highlighting some of these efforts titled, “Sustainability in Tourism, Hospitality, Education, and Agriculture” (linked below). Pioneers in education have focused upon imbuing students with knowledge about sustainable practices, and cultivating in them a mindset to prioritize environmental concerns in their professional and daily routines. Others have targeted their education and brainstorming efforts on tourists and hospitality operators, seeking plans and ideas to help them adopt eco-friendly practices and utilize resources more efficiently and effectively. The same strategy is being incorporated in agriculture. Still other institutions are implementing cross-cultural research programs, which help illuminate student researchers to the environmental trials faced by people in other parts of the world, and to encourage out-of-the-box thinking for resolving problems at the local level.

Students and faculty from Nepal’s Gate FAB Vocational School and the Netherland’s NHL Stenden University.

The Nepal Forum of Science Journalists organizes numerous events wherein researchers of various fields can share their work in front of journalists from a number of media outlets, to help spread the word and invoke increased interest and participation from the public and potential funders. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) provides funding for a whole host of projects in Nepal, including a community forestry project, early warning systems program, an animal conservation and restoration program, among others. Non-governmental organizations such as ICIMOD, Action Aid, Practical Action, Volunteer Corps Nepal, and EALS Global (my own organization), and many, many others, are taking the lead in implementing projects to minimize the damage from disasters, increase environmentally-friendly food production, assess risk areas, create sophisticated early warning systems for disasters, and contribute wherever else the needs are strongest. The government of Nepal works in tandem with all of these endeavors to provide funding or practical assistance where able.

National Forum of Science Journalists meeting to discuss climate change and agriculture in Nepal

While the world’s political class drags its feet on addressing the necessary large-scale problems, a growing number of regular citizens is expending great energy with what limited resources they have. Their collective efforts alone may not be enough in the larger picture, but they will help people weather the impending storm for as long as possible until governments take these issues seriously. As a reader of this publication you, too, can help by donating or volunteering with any of the above groups whose names include links to their respective websites (or, participate with any other organization whose work you admire). With citizen-centered collective efforts being all we’ve got right now, every contribution—no matter how tiny, and in what form—helps. Thanks for reading.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

To read the Sustainability in Tourism, Hospitality, Education, and Agriculture series, see below.