Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

As Kukur Tihar approaches, one cannot help thinking about the plight of so-called street dogs in Nepal. For those who don’t know, people in Nepal celebrate Kukur Tihar on or around the day of Naraka Chaturdashi (the 14th day of the Krishna Paksha) during the Tihar festival (generally mid to late October). On this day, dogs become the center of attention, celebrated as the symbols of Yama—the deity of death—venerated for their roles in warding off evil from people’s homes, and their loyalty to their human companions. Yet, in the evening time on this very day, the tendency is for worshippers to blow off fireworks thereby traumatizing the dogs they celebrated only hours earlier. Such is the ironic position of the dogs living untethered to any specific human abode in and around Kathmandu.

Even referring to the many thousands of dogs living this way in Kathmandu as ‘street dogs’ carries the slight stink of pejorative. In one somewhat popular travel blog, for example, the author attempted to distinguish between “street” dogs and “stray” dogs. The former, in his view, are those with a human owner somewhere, but are simply neglected or otherwise left to their own devices. While “stray” dogs comprise those without any human owner. This inartful and semantically challenged distinction actually misses the point altogether. There are in fact dogs all over the streets of Kathmandu at any given time, and some of them do indeed have a human-managed home to return to at night. The issue isn’t whether a specific person “owns” a specific dog, what’s important is how any given dog or dogs are treated. Just as the launching of dog-terrifying fireworks on a day to venerate dogs is contradictory, so too is the culturally powerful love of dogs in Nepal juxtaposed with the conditions under which far too many dogs spend most of their time in the streets.

Photo by Rob Vanwey

To begin with, not all dogs one sees on the streets are the same. If we are referring to “street dogs” as those that are essentially indigenous to the streets, people are generally talking about those breeds readily identifiable as intrinsically Nepali. Often these dogs belong to one of innumerable generations that have spent their entire existences out in the urban wilds. In contrast, there are those left behind by immoral humans who chose not to or simply were no longer able to care for them; these typically comprise breeds far more familiar to non-Nepalis, such as golden retrievers, shepherds, or cocker spaniels. Obviously, an abandoned dog unfamiliar with the abundance of noises, traffic, and certain cruel humans that fill the streets is going to have an extremely difficult time surviving for long.

But the reality is that both the “indigenous” street dogs and the abandoned ones equally share in the cruelties and travails of living in this chaotic urban environment. There has been a myth perpetuated, one that I myself once believed, that the so-called indigenous street dogs suffer less than their abandoned counterparts resulting from some DNA-enabled advantage. The Nepali Times pointed out that the street dogs live healthier lives than their “inbred pure breed” counterparts because the former “are less prone to congenital diseases,” and that these dogs have a certain amount of “street smarts.” While this is true to the extent that “pure bred” dogs often suffer maladies from the way that process is conducted (i.e., frequent inbreeding or malnutrition), when it comes to the perils of street living, all dogs are created biologically equal.

Researchers publishing in the journal Parasites & Vectors came to this conclusion about the dogs they studied. They wrote:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of different VBP [vector-borne pathogens] in stray dogs living in the metropolitan area of Kathmandu, Nepal, and to assess different traits as possible risk factors… A total of 81.43% of the dogs were positive to at least one of the VBP tested. Co-infections were detected in 41.43% of the dogs.

In other words, well over three quarters of dogs living on the streets suffer at least one ailment, and nearly half suffer two or more. So, there is no question that living on their own brings to dogs many maladies from the streets, and by virtue of their lack of ownership—if you will accept that distasteful term—few ever receive any treatment. So that brings us to the core of the question we want to explore here… whose job is it—or should it be—to take care of the dogs no one wants or claims as their own?

We make this query in the context that in both of our experiences, there is no question that people living in Kathmandu truly care for the well-being of the unclaimed dogs in their midst. While we might quibble over the seemingly alarming trend of interest in adopting pure breeds, we simultaneously believe this has in no way eroded the respect and love people have for the street dogs. Where purchasing versus adopting has had an impact, perhaps, is in the availability and cost of providing necessary medical care for the street dogs. By this we mean, our fear is that as “pet shop” dogs become more popular for those looking for canine companions, street dogs are increasingly being left behind as caring for multiple dogs is not feasible for many people. Regardless, claimed or unclaimed, dogs deserve the right to life and happiness as much as anyone… so whose job should it be to see to it that their suffering is alleviated?

Rescues

There are many people doing great work in Nepal caring for injured or ill dogs (and many other animals). One organization with which we are both familiar is Let’s Care Nepal. Their stated mission is as follows:

Protecting community dogs and animals from all forms of abuse, cruelty, and torture is the main focus of the work. In order for this to happen, Lets care Nepal could not limit its program to saving animals and providing for their medical requirements… we promote animal welfare and work with government agencies and other organizations with similar visions. We believe that ending factory farming and other forms of animal exploitation should be a goal for every individual, organization, and government.

We are both well acquainted with the President of that organization, Tularam Rajbanshi, who is a certified veterinary technician. Tula, as we fondly refer to him, spends many long days treating dogs hit by cars, attacked by other dogs, abused by people, or simply ill from the various pathogens floating around the streets. Let’s Care Nepal operates primarily on donor funding, meaning its ability to perform is often hindered by financial obstacles (see all their great work at their Facebook Page). There are many other organizations like this—and all seem to encounter the same financial obstacles.

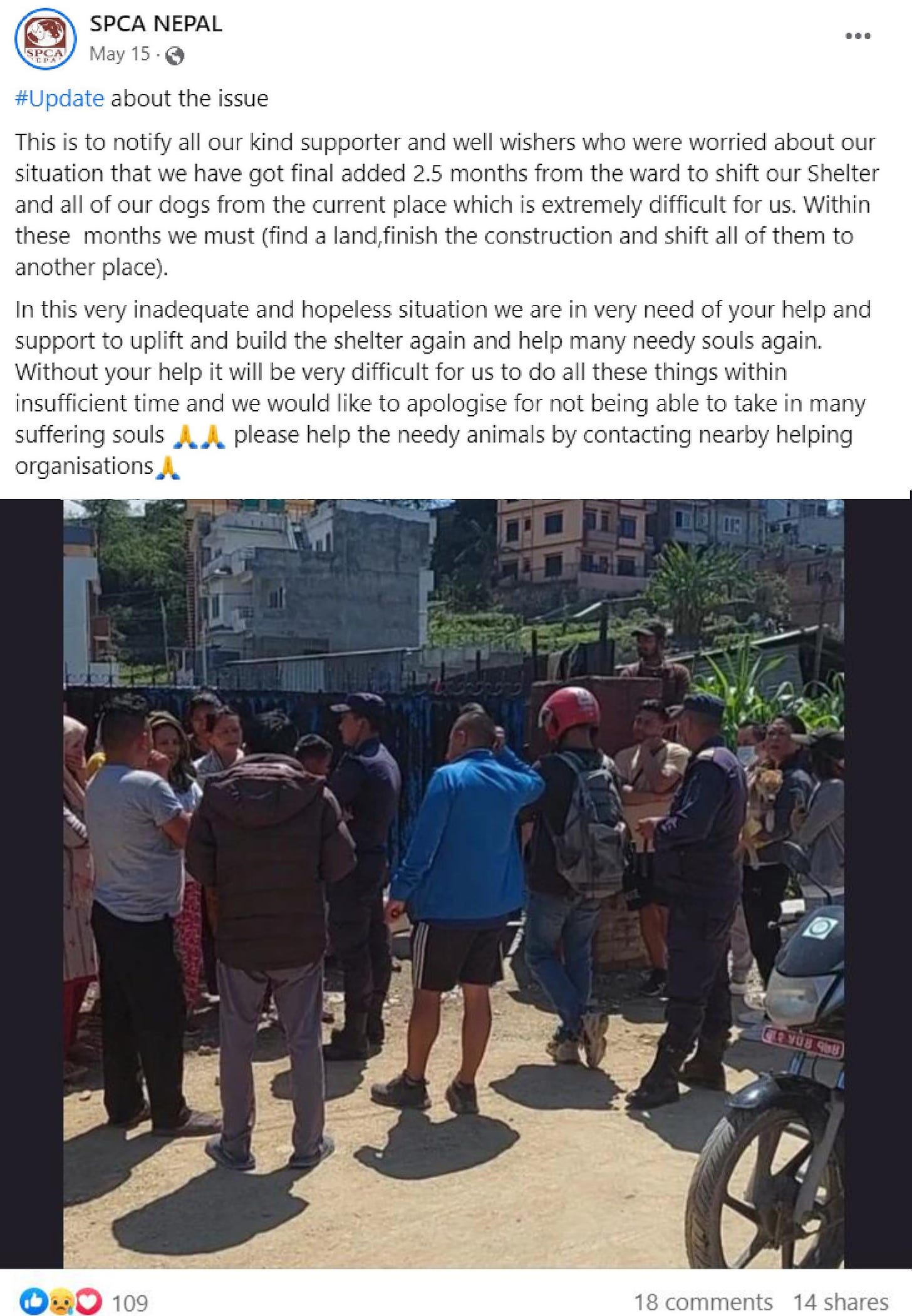

Associated with a lack of funding for necessary equipment is the problem of physical space. Many rescues simply cannot hold the number of animals that require treatment, meaning that often they are forced to treat and release. In the case of an injured or ill animal, re-release to the street while in a compromised condition leads only to more suffering or even death. Oftentimes the problem rescues have is that the incoming volume is simply too large compared to their available space. In other cases, however, rescues face protest from their human neighbors, such as in the case where the SPCA Nepal reportedly was forced out of their building allegedly on health concerns raised by members of the nearby community.

Whatever the circumstances, one thing is clear. Operating exclusively under a private donor paradigm will never be sufficient to solve the problem of street dogs in Nepal.

Example to Learn From

Like in Nepal, thousands or even millions of animals call the streets of Thailand home. There, the Soi Dog Foundation has undertaken a program it calls the CNVR (catch, neuter, vaccinate, return). It conducts this program on over 17,000 animals a month. Soi Dog Foundation operates ten mobile clinics across Bangkok, as well as several in other Thai cities. As a result of its efforts, Bangkok has seen a 20% reduction in its street dog population. Moreover, of those still on the street, incidents of malnutrition and illness have vastly reduced. Soi Dog Foundation also puts forth considerable effort into its vaccination program. This has led to a marked reduction in rabies among dogs.

That foundation’s annual income exceeded $20 million USD in 2022, according to its report to the Thai government. Through online fundraisers, the foundation raised over $158,000 USD, but it is not clear from where they received the remaining funds. In any case, this organization—which operates in eight different countries—has shown that these programs work to reduce the population size, and the pain and suffering of animals relegated to living in the street. Their program has seen more than 196,000 animals neutered and vaccinated; 17,639 received veterinary care; 528 found new permanent homes; and they created shelter space for over 1,000 dogs and cats, just in 2022. We believe with proper coordination, organization, and funding, Nepal could see similar successes.

Mitigating the Problem in Nepal

Approaching problems of extraordinary magnitude is daunting, to say the least. When an obstacle seems utterly insurmountable, people tend to raise their hands in frustration and resignation. Nonetheless, all big problems are really comprised of a series of smaller ones. Tackling the smaller issues, one at a time, erodes the profundity of the larger problem, and greatly enhances the probability of eventual success. Resolving the street dog problem in Nepal would benefit from just such an approach.

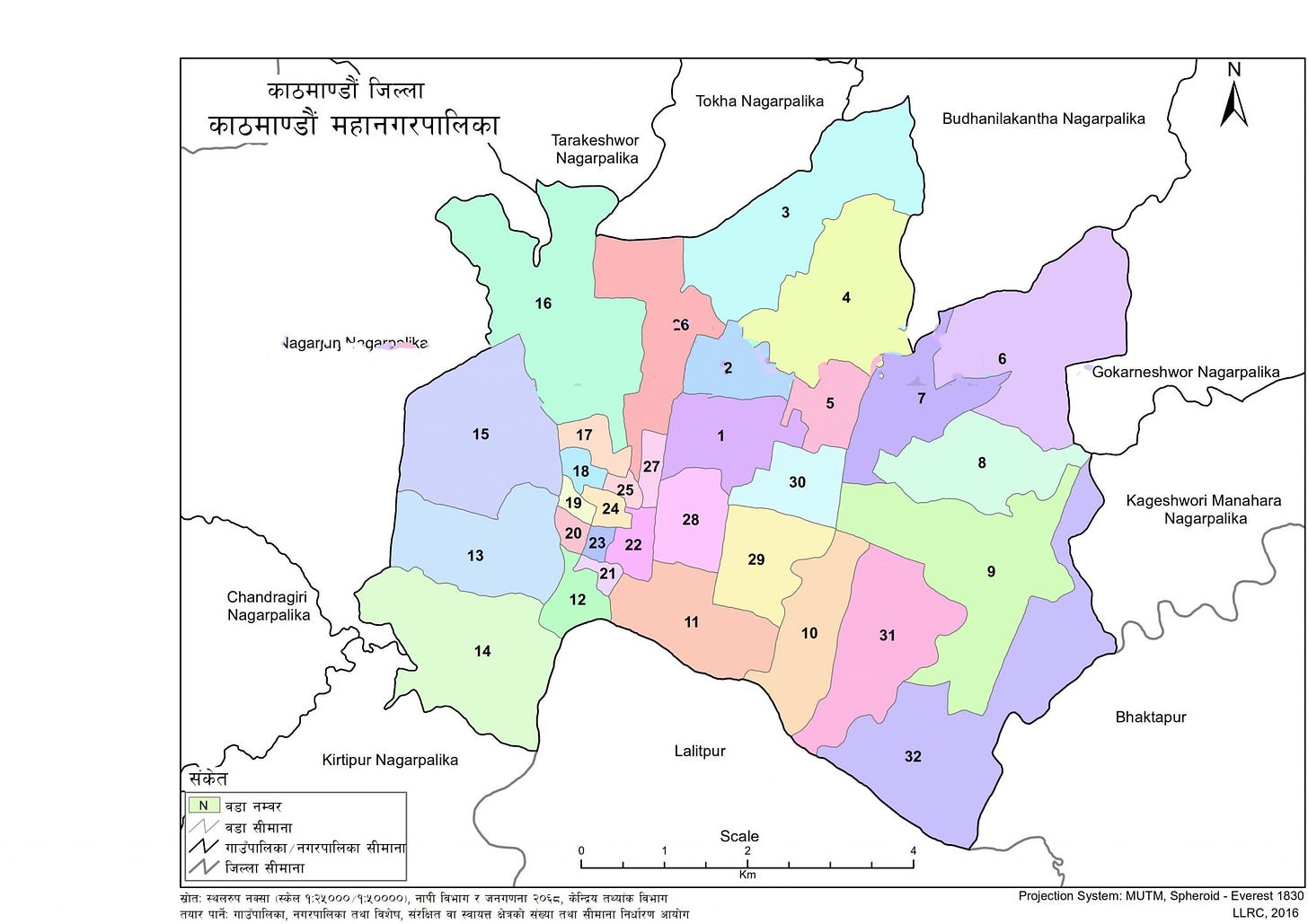

Kathmandu consists of 32 wards, with populations as low as 7,619 (Ward 24) and as high as 84,441 (Ward 16). Rather than attempting to resolve the issue across the vast expanse of the entire city, we suggest considering implementing a pilot program in one or a few wards. This would lower the number of dogs at issue, thereby reducing the costs of maintaining any such program over time. Moreover, the stakeholders would include the humans living in the ward. If the humans of a ward take ownership of the street dogs within their geographic boundary, they would incur immediate benefits both for the animals and themselves. This, in turn, would build the motivation to continue the program and eventually expand to neighboring wards.

Source: Nepal Archives

Establishing a temporary shelter for a given ward would provide locals a place to bring sick or injured animals. In the current circumstances, some local communities do not have a veterinary clinic nearby leaving good Samaritans with limited options to help an animal in need. Creating a community-based center for such treatment would solve that problem. To further bolster the effectiveness of such a facility, it could employ an animal control officer who would assist with collecting animals in need and delivering them to the clinic. The clinic itself would require maybe one veterinarian and one vet-tech to start, along with a few staff members to care for the animals (feed, water, and clean) and look after administrative functions (like answering phones, keeping paperwork, and so forth). As the Soi Dog Foundation has shown, implementing such a program would vastly decrease cases of rabies and the population of street dogs, and would mitigate the suffering of so many of them. Moreover, people would be more inclined to help knowing they can do so right within the confines of their own community.

Starting with a ward-based solution would also make the funding problem more manageable. For example, if the government imposed a once-per-year fee of just 100 NPS per person, even the smallest ward (24) could raise as much as 700,000 NPS per year. Allocating this amount to the costs associated with this program would go a long way toward assisting with the dog issue in the ward. As people see the fruits of such a program, undoubtedly many would be inclined to contribute even more to see the program reach the highest level of success. Furthermore, by directing the funds in order of priority, solving certain issues could also diminish some of the others. For example, focusing on spaying and neutering first will lower the population and reduce the number of vaccines needed down the road.

We consulted with several veterinary professionals both in the USA and Nepal. From those conversations, we propose the following as one suggestion for initiating and conducting an effective “street dog management” program.

Initiation

As we mentioned above, imposing a very slight annual fee (~ 100 NPS) will provide some of the seed costs to build a ward-based shelter. Starting in Ward 24 or another of lower population would enable organizers to tackle the problem at a small scale first. One obvious challenge involves finding a sufficient facility to house the clinic as it would also require space to board some number of animals (that number would be determined based on the expected needs of the ward). To assist in acquiring the property and developing the clinic facilities, external donors might be needed. Unlike the current paradigm, however, this program could continue its operations without further external donors as it would be funded by the imposition of a small, annual community fee. Additional donations would simply be a plus. Thus, procuring a sufficient donation to assist with the launch should be possible. Part of the initiation process includes finding personnel. As noted above, a good start would see the hiring of a veterinarian, vet technician, a few staffs to care for the boarded animals, and an office administrator.

Early Operations

The first step in implementing the operations portion of the program means collecting street dogs for treatments that will enhance the safety of the community and the well-being of the animals themselves. Collected animals would be neutered or spayed and given a rabies vaccination. Additional treatments can be provided to the animal as needed (and available). According to the experts we spoke with, the proper recovery time for spayed female dogs should be a minimum of 2 weeks. Male dogs require a minimum of 1 week to 10 days; both need a recheck prior to being released. Early release will lead to further trauma to the dogs, especially females, and would contradict the purpose of the program, so planning must be done accordingly. These two procedures—spay/neuter and rabies vaccination—lead to immediate results. Those dogs will no longer be contributing to the population growth of street dogs in the ward, and the humans will find solace in the fact that the chances of encountering a rabid dog is now diminished.

Treatments of certain maladies should take priority over others. For example, Sarcoptic Mange (also known as canine scabies) and Demodectic Mange (also known as red mange or Demodex) are endemic in the street dog population. The former, Sarcoptic Mange, is extremely contagious and can even pass from canines to humans. It is imperative, therefore, to treat this affliction whenever it is detected. Left untreated, it can cause:

Extreme itchiness

Redness and rash

Thick yellow crusts

Hair loss

Bacteria and yeast infections

Thickening of the skin (advanced cases)

Lymph node inflammation (advanced cases)

Emaciation (extreme cases)

Demodex, while less dangerous than Sarcoptic Mange, poses a risk to dogs with immune deficiencies, such as puppies, elderly dogs, and those already compromised with another illness or injury. Thus, providing medical care for either of these maladies will enhance the quality of life for dogs and reduce the risk of a zoonotic transmission to humans. Another infliction that should take priority is Leptospirosis. According to the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease that occurs worldwide and can cause serious illnesses such as kidney or liver failure, meningitis, difficulty breathing, and bleeding.” Leptospirosis is spread through direct contact with contaminated animal urine (including dog urine), or through eating food or drinking water contaminated with infected urine. As Nepal already faces a high prevalence of water-borne diseases, especially during the monsoon, vaccinating dogs against this illness greatly enhances human safety.

See more about health issues related to water-borne contaminants here:

In the Future

Establishing a community treatment program for each ward of Kathmandu will swiftly reduce the number of occurrences of various diseases and improve the lives of both humans and dogs. In addition, such a program will humanely lower the overall street population in each ward, and Kathmandu on the whole. Once that is accomplished, focus can turn to other issues. Some ideas include:

Implementing a microchip program to identify lost dogs and return them to their homes;

Applying more vigorous flea and tick treatments, which also will benefit human health;

Raise adoption numbers of street dogs as more of them will be healthy and thus more attractive to adopters; and

Improve overall hygiene in the ward, which will enhance the health and wellness of all living creatures, humans included.

Nepali people are among the most compassionate of any society we have encountered across the globe. Their love for dogs shows in the way many people look after and treat the street dogs that live in their own neighborhoods. We believe mitigating the street dog issue in Nepal is possible with collective effort. Until now, it seems probable that so many people have succumbed to the “big problem” analysis, where one views large problems as so insurmountable as to be impossible to solve. That is why we have humbly offered the proposal detailed here. No one wants to see dogs suffer, but many people simply do not know what they themselves can do, especially in the instances of possessing limited means. We hope the ideas we have offered dissipate the big problem by dissecting it into smaller, manageable ones.

Photo by Rob Vanwey

Correction: Rob Vanwey wrongfully identified Tularam Rajbanshi as a veterinarian. He is actually a certified veterinary technician. I apologize for the mistake.

***

Thank you to my special guest author Tammy Conti. She has been a dog trainer and animal advocate in the Western New York (USA) area for the past 25 years. You can find more about her work on the Dog Training with Tammy Facebook Page.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

For information on protecting dogs and other animals from natural disasters, click below.