Introduction

On March 8, 2014, the most remarkable and tragic sequence of events in aviation history began over the area where the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea meet. A Boeing 777-200ER (a.k.a., a Triple-7), tail number 9M-MRO, operated by Malaysia Airlines, disappeared from civilian radar at 1:21 am Malaysia Time (5:21 pm UTC), never to be heard from again. The story captured the news in a way few ever do.

After all, 239 people—227 of them passengers, the rest crew—simply vanished into the night despite riding aboard a vessel that could fly with a maximum weight of 297,550 kg (656,000 lbs.), whose body extended 63.7 m (209 feet) from tail-to-nose, with wings that spanned 60.9 m (199.8 feet), and a tail that soared 18.5 m (60.69 feet) upwards.

First introduced in 1990, the Triple-7 was, and arguably still is, one of the most advanced long-haul aircraft in the world. Besides the size and sophistication of the jet itself, people wondered how the heck could a commercial airliner go missing in this world of satellites and surveillance?

For a size comparison, here is the Triple-7 lined up behind a Boeing 737. Source: Ken Ken on Pinterest

Fast-forward a full decade, the mystery of MH-370 remains unsolved. In 2023, Netflix released a 3-episode miniseries it called a ‘documentary’ exploring the current state of the puzzle. The program introduces the views of journalists, independent researchers, family members, and others determined to figure out what really happened. Titled “MH370: the Plane That Disappeared,” each episode is more of a narrative about the characters than the plane.

The series explores what each of them thinks, the theories they have proffered, and the conspiracies they suspect. Critics called it “exploitative… for giving weight to unsubstantiated claims.” While an entertaining item to watch, it does not provide any real insight into the incident itself. Others have done a much better job toward that end.

As the evidence introduced below will show, whatever happened to MH-370, it was almost certainly done intentionally. Because this is a rather complex case, this article is just an investigation into who could have taken control of the plane and how, not where the plane ended up or why. The latter will be explored later. Unfortunately, the evidence we have is circumstantial, but it does help narrow the suspect list.

Operating a Triple-7 is not something easily managed by the untrained, and for the reasons I give below, even if there were knowledgeable hijackers aboard, it seems very unlikely they were the culprits. The goal here is not to contribute to wild speculation so many have unabashedly offered, but to look at what theories or ideas remain possible in light of all the evidence collected so far.

Every piece of evidence used in this report will be cited via underlined hyperlinks, with abbreviations explained as needed. For media files, timestamps to the pertinent parts are provided as able. This way, you can do your own examination and compare it to mine.

Finally, the point of my analysis is not specifically to find a place to lay blame, though that is unavoidable. The deed, however dastardly, is done. But this incident is critical in determining how such a massive jetliner could evaporate from existence with so few traces left behind. After all, answering such a question matters for the future of aviation and matters, as importantly, to the family and friends of the 239 people whose fates remain unknown.

As Petter Hörnfeldt, a Boeing 737 pilot and trainer, and host of the Mentour Pilot YouTube Page put it, “The only thing I want to achieve is to get the search going again for the sake of the families left behind… Please get the boats out there and let’s get to the bottom of this… literally.”

* * *

A note on quantities: Because in aviation flight levels are measured in feet, distance is calculated in nautical miles, speed is given in knots, and other measurements are offered via the metric system, this article will provide the appropriate quantity as is typically used in the aviation context with equivalents given where necessary for clarity. Apologies for the clutter this may cause, but readers of this blog reside in both universes of measurement systems (metric and imperial), and probably few are pilots or seafarers operating in nautical miles.

Regarding flight systems, which are important to this story, I will use their full name throughout except in a few cases where the short form is easier to remember. The citations that provide a page number only are referencing the final investigative report issued on March 8, 2014.

The timeline of events

Malaysia Airlines operated the flight designated as MH-370 daily from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing. The distance between the two airports is 2,375 nm (2,733 mi; 4,399 km), well within the overall range of the Triple-7. The time for this trip was expected to last 5 hours and 34 minutes, with no anticipated weather or other delays. Malaysia Airlines had filed the flight plan with the appropriate authorities twelve hours before departure time (p. 285).

Flight and cabin crew members arrived on time with none indicating any problems, illness, or fatigue. The captain, 53-year-old Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah, signed in for duty at 22:50 MYT (14:50 UTC), while the co-pilot, Fariq Abdul Hamid, signed in at 23:15 MYT (15:15 UTC) (p. 286). **Note the time difference between UTC and MYT (Malaysian Time). All times for the flight events will only be given in MYT from here on.

Fariq Abdul Hamid commenced his shift that day in a unique position. This trip comprised his last training flight before becoming certified as a full-fledged first officer on the Triple-7. He had joined the airline seven years before, holding ratings on the Boeing 737-400 and Airbus A330-300. He had a total of 2,813 flight hours, with just thirty-nine on the Triple-7 (p. 29).

Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah joined Malaysia Air in 1981. He had more than 18,400 hours of flight experience, with 8,659 on the Triple-7. In November 2007, he became a Type Rating Instructor and Type Rating Examiner (pp. 26-27). Eighteen thousand hours is an extraordinary amount of experience, with a great deal of it on the Triple-7; in fact, Shah was one of the most experienced pilots in all of Malaysia at the time.

The cabin crew consisted of ten attendants, ranging in age from 34 to 55, with six of them male and four female. Among them they averaged 21.3 years of experience. The attendant supervisor (purser) himself had thirty-five years of experience (pp. 31-35). Overall, this was a very experienced crew handling this flight.

**Flight Crew denotes those who operate the aircraft. Cabin Crew describes the flight attendants.

At 23:56:08, one of the pilots entered the airline details, flight path information, and aircraft provisions (fuel, weight, V-speeds, etc.) into the Triple-7’s Flight Management Computer. The Flight Management Computer steers the autopilot and controls other automated features of the aircraft.

The Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) relayed this inputted information to the airline’s dispatch and maintenance centers (p. 51). ACARS is a data link system that passes text-based information back-and-forth among flight crews and airline personnel working in ground operations.

It transmits via VHF or the satellite communications system (SATCOM). VHF (Very High Frequency) is short-range communication limited by line of sight. SATCOM works almost anywhere in the world, relaying signals among the aircraft, ground stations, and satellites.

Sorry for the jargon, but these systems become important later.

The amount of fuel onboard read as 49,200 kg, per the ACARS. Shah himself ordered this amount, which would cover the expected duration of the flight, an additional two hours, plus reserves (p. 1). This amount was not unreasonable as commercial flights must carry enough fuel for delays or diversions—reserve fuel cannot be used for these purposes—and absent emergencies, commercial flights have a minimum remaining fuel requirement for when they land. So far, all was normal.

Dispatchers can use ACARS to send individualized text messages back-and-forth to the flight deck similarly to SMS. ACARS on MH-370 also had a pre-set timer wherein it would automatically send information via either SATCOM or VHF every 30 minutes to the dispatch center. This included general information about the flight, such as speed, altitude, and remaining fuel, for example.

In the event of a failure of either protocol, the ACARS automatically switches to the remaining one. If the ground station receives no broadcast after the 30-minute interval, it will automatically ping the plane’s ACARS in an attempt to detect it. At the same time, the airline’s dispatch is required to manually send its own message to try to reach the ACARS or to diagnose any potential problem behind the unit’s silence. This is to ensure continued contact with ground operations as they cannot always reach long distance flights by radio.

Between 00:25:53 and 00:26:45, MH-370 and Kuala Lumpur Delivery Control exchanged several messages. One key part of that conversation was that Control instructed MH-370 to ‘squawk’ at 2157. An instruction to ‘squawk’ means to set the aircraft transponder to the given value. A flight’s transponder code travels with it over the entirety of its flight so ATC across jurisdictions can readily identify it on their radars.

Generally, transponders can squawk between 0000 and 7777, though some of these frequencies are reserved for specific purposes. For example, 7500 is reserved for hijackings, 7600 for communication failure, and 7700 for all other emergencies. Pilots can discreetly enter these frequencies in flight, and ATC will see an instant alert on their displays offering them some understanding of what is happening on the plane without any verbal communication.

During the time the crew talked with Delivery Control, the passengers boarded and ground crews loaded cargo and luggage. Some have made hay about the fact that the cargo included lithium batteries, but no evidence has suggested that those batteries had anything to do with future events. Maintenance reports indicated an airplane in good condition; it endured only one major repair two years before when the right wing suffered damage at Pudong International Airport in Shanghai, China, in 2012 (p. 44). The wing had been repaired immediately and no other airworthiness issues were reported on the aircraft since.

A more interesting maintenance entry was found in the Malaysian Air (MAS) Technical Log Book, the document where pilots enter any defects they discover both to notify later flight crews and to alert maintenance. On March 7, 2014, the day before the incident flight, the flight deck’s oxygen system underwent replenishment, according to the log. Topping off the oxygen is, itself, common because on each new trip the level is reduced a tiny bit as pilots check that the oxygen masks are in working order, thereby bleeding off just a little. The report noted:

[T]he MAS Minimum Equipment List is 310 psi at 35°C for 2-man crew and with a 2-cylinder configuration (as installed on MAS B777 fleet).

It has been the practice of the airline to service the oxygen system whenever time permits, even if the pressure is above the minimum required for despatch.

During the Stayover check on 07 March 2014, the servicing on 9M-MRO was performed by the LAME [Licensed Aircraft Maintenance Engineers] with the assistance of a mechanic, as the pressure reading was 1120 psi. The servicing was normal and nothing unusual was noticed. There was no leak in the oxygen system and the decay in pressure from the nominal value of 1850 psi was not unusual. The system was topped up to 1800 psi. (p. 47)

What is interesting is that the report does not identify who requested the top-off. The psi level at the time of the fill-up was well above the minimum, so there was not a specific need to add to it. On the other hand, top-offs routinely happen whenever the aircraft will sit for some length of time. Therefore, this may just have been normal maintenance conducted at a purely coincidental time. If one of the flight crew specifically ordered it, however, the implications could be more significant. (The reason why is discussed later).

At 00:27, the crew requested pushback and startup of the engines. The Tower cleared them for takeoff at 00:40. The aircraft left the ground at 00:42:10. The pilot flying was Hamid; Captain Shah was the pilot monitoring the instruments and handling the radio communications.

Fifty-three seconds after takeoff, the Departure controller cleared the flight to proceed directly to its first significant waypoint, IGARI. This provided the aircraft a shortcut, bypassing a meandering series of lesser waypoints usually used to coordinate traffic more efficiently for landings and takeoffs at the airport. An allowance to take such a shortcut often happens during times of low airspace volume because the controller does not have many aircraft approaches or departures to negotiate. In effect, the skies are wide open.

All communication to that point sounded normal, with no indication of stress or trouble (FULL_ATC; 0:00 – 5:29); Departure then handed off MH-370 to Lumpur Control (KLC), the regional ATC. At 00:46:51, Captain Shah radioed KLC to identify the flight. Lumpur Control manages air traffic across Malaysia’s airspace up to its borders with neighboring jurisdictions.

Whenever an aircraft switches from one controller to another, it is standard practice for the radioing officer to offer a greeting to the new one and identify the flight by its designation on the next frequency. This helps each layer of ATC stay apprised of new aircraft entering their control area.

The first series of communications between MH-370 and KLC allowed the plane to ascend to the cruising altitude that it planned to follow for the majority of the flight—35,000 feet (FL350). One oddity occurred during these exchanges.

At 00:50:06, KLC control gave the first authorization to climb to FL350. Immediately after, Shah acknowledged the directive, repeating the authorized altitude and his flight number as per normal protocol. Eleven minutes later, Shah radioed that the flight had reached and was maintaining 35,000 feet, and ATC acknowledged. About 8 and a half minutes after that, however, Shah repeated that MH-370 was maintaining 35,000 feet (pp. 1-2).

Shah’s second announcement stood out to some pilots because the repetition was neither required nor necessary. Petter Hörnfeldt offered two explanations that mirrored what other pilots have said: either Shah forgot that he had already acknowledged ATC and simply did it again out of courtesy, or he was preoccupied with something happening on the flight deck and perhaps restated it because of some distraction.

If the latter, then this could mark the start of unusual activity on the flight deck. The official report also commented on the repeated statement, but found no significance in it (p. 287). At 01:07:29, the ACARS transmitted MH-370’s location, still enroute to IGARI, with 43,800 kg of fuel remaining and climbing through 35,004 feet.

KLC called the jet at 01:19:24, advising the crew to switch channels to Ho Chi Minh Control (HCM), the controller for Vietnamese airspace, on channel 120.9. Shah responded with the last thing anyone would hear from him over the radio: “Good Night, Malaysian Three Seven Zero.” This happened immediately, at 01:19:29 (FULL_ATC; 5:30 – 7:06). This final ‘good night’ also contained one curiosity.

Following protocol, the proper response would have been for Shah to repeat the new frequency along with the flight’s call sign. That he did not do so may simply indicate a habit among pilots in the region, especially on night flights where radio traffic tended to be quieter and perhaps more informal. Or, as Hörnfeldt suggested about the earlier anomalous transmission, maybe Shah was still busy with something and inadvertently shortened his response. The final report did not comment on this lapse in protocol.

No More Talk, Just Unexpected Flying

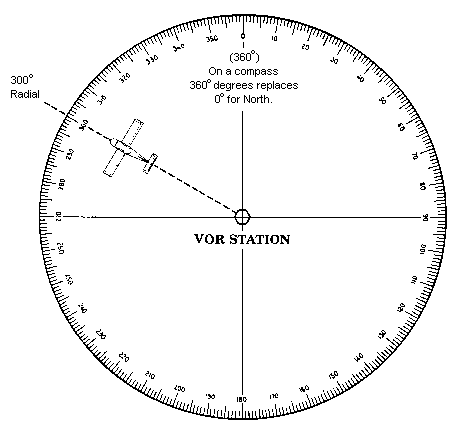

**Before proceeding, here is a quick note on headings, as they are important to the upcoming portion of the narrative. Headings refer to the directions of a compass. North is represented by 0°. From there, headings follow the cardinal directions in a clockwise motion—thus, East = 90°, South = 180°, and West = 270°.

Malaysian and Vietnamese controllers had an informal arrangement regarding handoff procedures for aircraft switching between their jurisdictions. Airliners generally just called in when released from the previous controller, but the expectation was to establish contact with the next controller within about five minutes.

The final report noted that the handoff by Malaysia ATC occurred about three minutes before MH-370 expected to reach the IGARI waypoint just inside Vietnamese space (p. 288). As such, MH-370 would have anywhere from 3 to 8 minutes before the Vietnamese controller would normally start looking for it.

It turned out that the plane reached the waypoint nearly two minutes sooner, at 01:20:31. At that moment, MH-370’s Mode S radar symbol disappeared from ATC displays. Only a minute after that, MH-370’s secondary radar symbol also disappeared. This drop from the displays was observed by KLC, but also the Thai and Vietnamese militaries (p. 3).

Mode S radar is a unique 24-bit address for each aircraft, assigned by its registering country. Like an IP address, the Mode S identifies the aircraft’s exclusive signal that broadcasts to and receives replies from local radar, locking in the unique identifier for that aircraft. In other words, it provides ATC with a display of that specific aircraft that cannot be somehow mixed up with any other nearby planes. This ensures ATC can observe the position, course, and identity of each aircraft within its coverage. It is displayed in accordance with the aircraft’s transponder code, described above. To purposely eliminate the Mode S signature, a member of the flight crew would need to turn the transponder to “standby” mode.

Another important feature of Mode S radar is the role it plays in the Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance Systems (TCAS). TCAS is used to avoid potential mid-air impacts with other planes. The system monitors airspace surrounding the aircraft, constantly broadcasting to and listening for replies from transponders of other airplanes. If it receives a reply, it calculates the flight paths of both to determine whether a collision might be imminent. When there are nearby aircraft but they do not pose an acute threat, TCAS issues a “Traffic Advisory” to put pilots on the lookout.

In the event it calculates a potential collision, it issues a “Resolution Advisory,” which consists of loud, explicit instructions to climb or descend. Under Annex 6 Part I of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) rules, all “turbine-engined aeroplanes of a maximum certificated take-off mass in excess of 15,000 kg or authorized to carry more than 30 passengers” must be equipped with an operating TCAS. Turning off the Mode S effectively disables the TCAS, which is a major violation for any commercial carrier.

To disable Mode S, someone in the flight deck needs to turn a knob on the transponder, as it is the transponder that conducts communication between the aircraft and ground radar. This knob is not in a position that would allow someone to mistakenly “hit” it into standby mode—it is not a mere ‘button,’ as some media have called it. Once the transponder is turned off, secondary radar—the kind that provides the most detail about airborne planes—can no longer detect the flight. Primary radar, however, still can, but more on that in a moment.

Investigators know that someone actively switched off MH-370’s Mode S because there are two transponder power sources—a left and a right. These are controlled by separate electrical busses. In the event that a power problem causes the transponder to fail, the still-operating bus sends a brief, low-power signal with a simple code to airline operations indicating an issue. No such code was received by Malaysia operations for MH-370 (p. 105).

Ho Chi Minh control seemingly captured MH-370 on its radar at 01:11:59. The blip remained on their screens until someone aboard the plane turned off the transponder at 01:20:31 (at or near the IGARI beacon). The Vietnamese controllers sent mixed messages to KLC controllers several minutes later, at once acknowledging that they had captured the plane on their radar but then denying that they had in virtually the same sentence (p. 15).

In later interviews between HCM controllers and investigators about this, it seemed the controllers were trying to cover up for their failure to attempt to contact MH-370 by radio for well after the time required by their own protocols. The Vietnamese duty controller (supervisor) told investigators that he had initiated calls to other aircraft on the existing frequency and on the emergency frequency of 121.5 MHz looking for MH-370 after it reached IGARI, but investigators found no documents or evidence to support this.

A recorded phone conversation between controllers at HCM and KLC further belied the notion that HCM controllers never saw MH-370 on radar. During the call at 01:39:06, HCM told KLC:

Yeah…yeah…I know at time two zero but we have no just about in contact up to BITOD…we have radar lost with him…the one we have to track identified via radar. [Emphasis added]

As secondary English speakers, and employing some industry jargon, the statement is a little confusing. What the Vietnamese controller told the Kuala Lumpur controller was that they saw MH-370 on radar up to 1:20 am, but they lost radar contact when the flight arrived at its next waypoint, BITOD (p. 15).

The final report states that investigators pointed out to the Vietnamese ATC supervisor in an interview that neither their SSR (Secondary Surveillance Radar) nor ADS-B (Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast) showed any presence of a “blip” of MH-370 at or near the BITOD beacon. The HCM supervisor could not explain why he mentioned BITOD at all. Thus, neither the report nor the substance of the interviews definitively concludes whether Vietnamese controllers were aware of when radar contact with MH-370 was lost (p. 15).

Evidence suggests the flight did in fact show up on radar, so the question was whether HCM controllers ever acknowledged or even noticed when it dropped off. If they did not notice right away, that was a major breach of duty as they knew the plane was coming into their airspace and their job was to monitor it and welcome it into their jurisdiction. If they did notice the blip drop off at 01:20, then why did they not follow up immediately with KLC, MH-370, or surrounding planes upon the sudden disappearance of the radar signature?

In any case, other radars also identified the presence of the flight. Aeronautical Radio of Thailand Limited picked up radar contact of MH-370 from 01:11 until the shutting off of the transponder at 01:20, but paid no attention to the flight as it was not within its jurisdiction, nor heading that way (pp. 18 - 19).

It is unclear if Thai controllers positively identified the flight as MH-370, or just that their radar captured a random plane that did not concern them. Whatever the case, investigators later confirmed that the associated ‘blip’ on their radar belonged to MH-370. In short, at least until 01:20, MH-370’s location and flight path was known with certainty by civilian controllers.

Malaysian military also captured a radar signature for the flight beginning at Kuala Lumpur and tracked it well beyond when MH-370’s Mode S disappeared. The Malaysian military employed primary radar, which did not require transponder signals to detect the flight. Primary radar simply bounces radio waves off of objects, irrespective of any transmissions (or lack thereof) by the object.

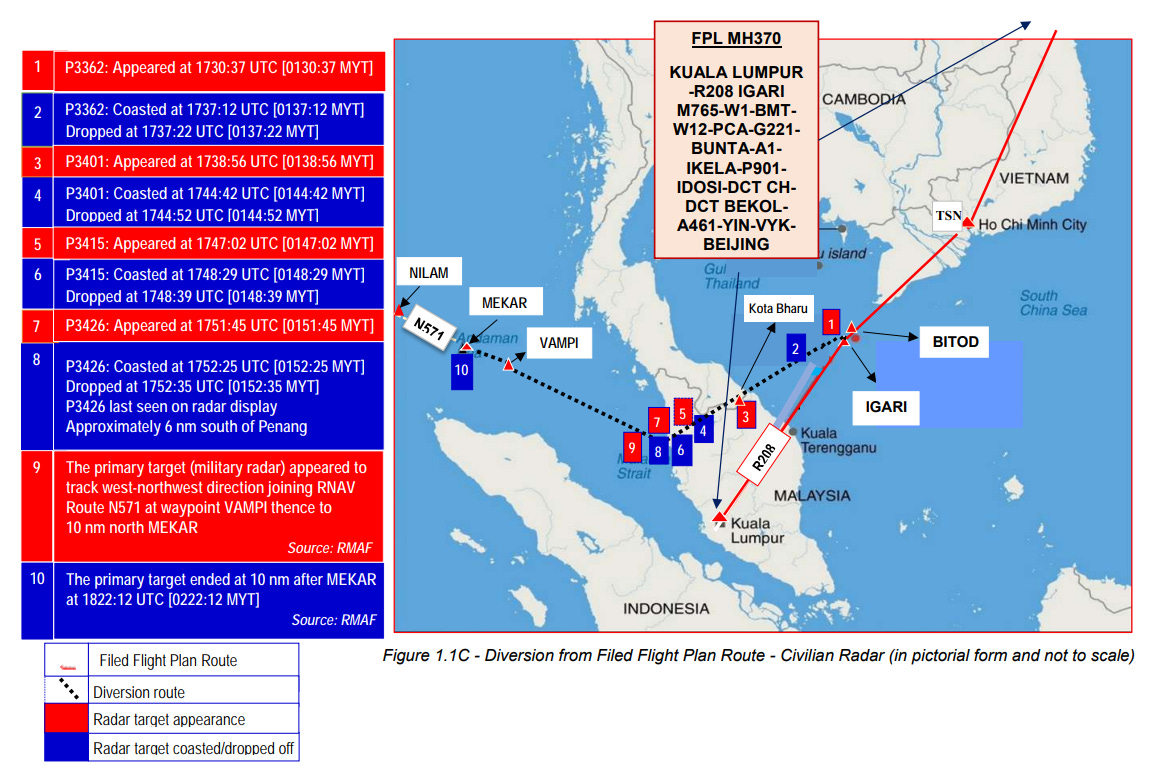

The military’s primary radar noted two maneuvers of MH-370 starting at 01:21:13, less than a minute after the drop in secondary radar coverage when someone shut off the transponder. First, the jet banked slightly right, followed by a sharp left bank to heading 273°, an effective U-turn on its flight path (p. 4).

The sharpness of the second turn appears to have been designed to avoid entering nearby airspace designated by the Thai military as an “air defense identification zone.” Crossing the border of that zone would trigger an immediate response from fighter jets or other Thai air defenses. It would also have quickly identified the flight. Thus, one might conclude that whoever was flying the Triple-7 did not want to garner that kind of attention.

It seems certain that the banked turn and subsequent flight was conducted manually. First, the bank angle—or, the steepness of the angle of the wings while turning—required to complete the maneuver exceeded the safety allowances of the Triple-7’s autopilot. To conduct a turn this dramatically, someone necessarily had to fly manually after disabling the autopilot.

Second, the flight path following the turn did not exhibit the smooth trajectory of auto-piloted flight. MH-370 made several heading changes that varied between 8° and 20°, its ground speed varied from 451 knots to 529 kts, and its altitude shifted from as low as 31,150 to as high as 39,116 ft (p. 4).

On this reversed path, MH-370 flew parallel to the designated flight highway M765, presumably to avoid other aircraft coming in its direction. Autopilot flies along the flight path entered into the Flight Management Computer, almost always along these aerial highways. If someone on the flight deck turned the autopilot to “heading” only, the plane would pursue a straight line in the direction of that heading rather than along any aerial highway, but it would not deviate left or right, and it would not change speeds or altitude.

To provide further clarity on the airline highways, all commercial aircraft follow predetermined routes, sort of like “roads” in the sky. Just like city streets, traffic can travel in either one or both directions on these routes. When two-ways, traffic in one direction is required to fly at a certain altitude while traffic going the other way flies at another, at the direction of ATC, and with at least 1,000 feet or more of vertical separation.

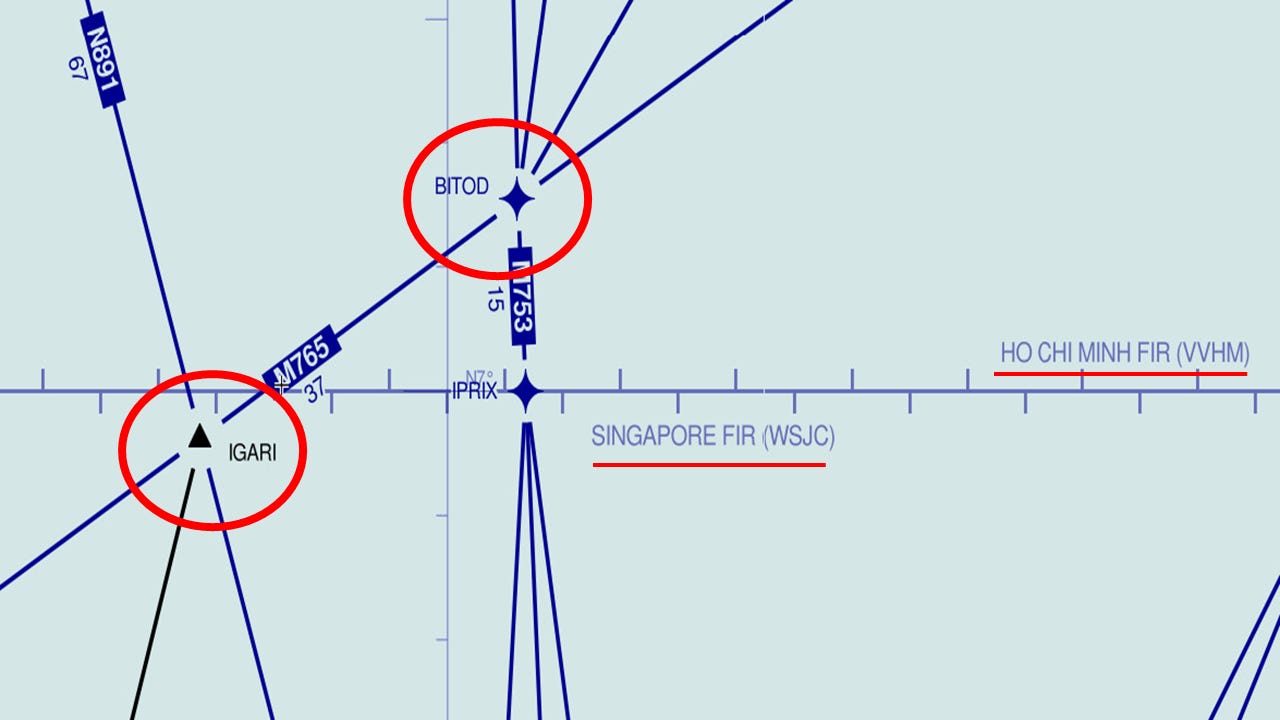

To avoid encountering traffic in either direction, a rogue pilot could follow a parallel path to one of these highways, but a few miles wide of the actual route. This would allow the pilot to maintain directional sense without revealing himself to other aircraft. Here is what the flight paths look like in the region where MH-370 conducted its circle-back portion of the flight. Notice the IGARI beacon at center-right, sitting at the intersection of M765 and N891.

Source: Sky Vector

MH-370 flew parallel to M765 on its northern side for some time before making a slight right turn at 01:37:59, to headings varying between 239° and 255° (west-southwest). This time adopting another parallel track, now with Airway B219, the plane flew toward Penang Island’s VOR (another type of directional beacon). The jet sped up to between 532 and 571 kt. (p. 4).

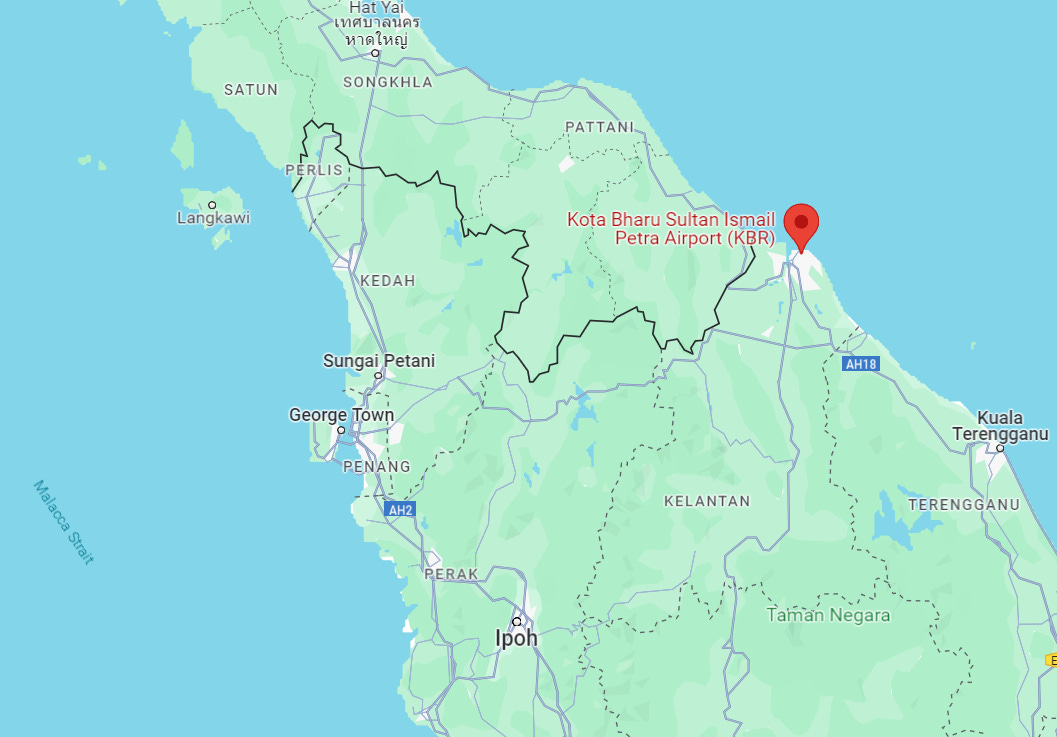

Altitude values given by the military for this segment of the flight seem unreliable, varying between 24,450 ft and 47,500 ft. No reason for the disparity is provided in the reports. Regardless, the directional and velocity information aligned with data from the Terminal Primary Approach Radar located to the south of the Kota Bharu–Sultan Ismail Petra Airport runway. That radar terminal observed the flight from 01:30:37 to 01:44:52 (p. 6).

Michael Exner examined the measured altitude of MH-370 during the time it traversed Kota Bharu’s primary radar coverage. Using range and azimuth data, along with a “phase correction” to reduce observational noise, Exner calculated the actual altitude. He concluded that the flight at that time was around 43,500 feet. Note that this altitude consisted of a height of more than 8,000 feet above MH-370’s permitted plan.

Exner also confirmed that the flight path from IGARI to the western side of Penang aligned with that denoted in the official report. Thus, the reporting of MH-370’s path was confirmed by multiple sources, eliminating any possible controversy about which way it went (some theories rely on this supposed controversy).

Source: Google maps

At 01:39:03, HCM Control contacted KLC Control asking about the whereabouts of MH-370, stating that it had not made verbal or radar contact. KLC replied that after waypoint IGARI, MH-370 did not return to their communication frequency (p. 240). KLC Control was referring to the last transmission in which Shah had replied simply, “Good night, Malaysia 370.” Put another way, that the flight did not return to KLC’s frequency indicated to them that it had also not returned to their airspace.

After HCM advised KLC controllers of negative contact, KLC sent a blind transmission to MH-370 (p. 243). The report does not specify the nature of the blind transmission, but often controllers will call the aircraft asking for it to “ident.” They do this when they suspect that the aircraft has a broadcasting problem but might still be able to receive incoming transmissions. Crews without broadcast capability can hit the ‘ident’ button on their transponder which will highlight them on ATC’s display. This also confirms to ATC that the flight can hear them even if it cannot answer. Of course, the ident button would not work if the transponder was off.

A few minutes later, HCM Control called KLC again and stated that MH-370’s radar blip disappeared at waypoint BITOD (the next beacon following IGARI). HCM also said that efforts had been made to establish communications by calling MH-370 several times for more than twenty minutes (p. 298). As noted above, investigators found no evidence of this attempt at communication to that point in time. They also confirmed that MH-370 never made it to BITOD.

These are the locations of the requisite beacons. MH-370 made its U-turn a little less than midway between them.

Meanwhile, the Malaysian military again observed MH-370 at 01:52:31, tracking it 10 nm south of Penang Island—Captain Shah’s hometown—on a heading of 261°, speed of 525 kt, and at an altitude of 44,700 ft (p. 4).

Bandar Baru Farlim Penang’s Location Base Station (LBS) detected a cell phone signal at nearly the exact same time. Although the detected signal only confirmed the phone as “on,” the phone company positively identified the signal’s associated phone number to that belonging to co-pilot Hamid.

Later tests conducted by the phone company revealed that the highest altitude at which it could recreate the signal connection was only 20,000 feet, but it cautioned that the test was not inherently scientific (p. 20). The final report does not explain the disparity between the cell phone test altitude maximum and MH-370’s altitude recorded by the military radar, a difference of 24,700 feet. Whatever the plane’s actual altitude at the time, the phone company confidently asserted the phone number’s identification.

At 01:57:49, HCM reported to KLC that call attempts on many frequencies and by aircraft in the vicinity received no response from MH-370. All evidence indicates that MH-370 was nowhere near Vietnamese airspace by then, so even if inclined to answer, whoever was flying MH-370 would never have received any of these messages. Neither of the civil air authorities could know this, of course (p. 243).

They also did not normally communicate with military authorities about civilian air traffic, and they did not have reason at the time to think they should try. At 02:03:23 Malaysian Air dispatchers sent an ACARS message to MH-370 requesting a response. As a reminder, the location of MH-370 did not matter to ACARS because it utilizes satellite communication. Nevertheless, the dispatchers received no response to the 02:03 attempt. The system kept trying for 40 more minutes:

The incoming downlink message at [02:03:24] showed the message failed to reach the aircraft. Messages are auto transmitted every 2 minutes and the message was retransmitted until [02:43:33] but all messages failed to get a response. Automated downlink message by ACARS showed ‘failed’ (pg. 114). [The last sentence indicates that the equipment aboard MH-370 must have been powered off throughout this 40-minute span].

Military radar recorded another course correction at 02:01:59. This time, MH-370 shifted from a west-northwest direction to a slightly northeasterly track. Radar showed the speed slowed to 492 kt. The report listed the altitude as 4,800 feet, though this appears to be a typo, perhaps meaning 48,000 feet instead.

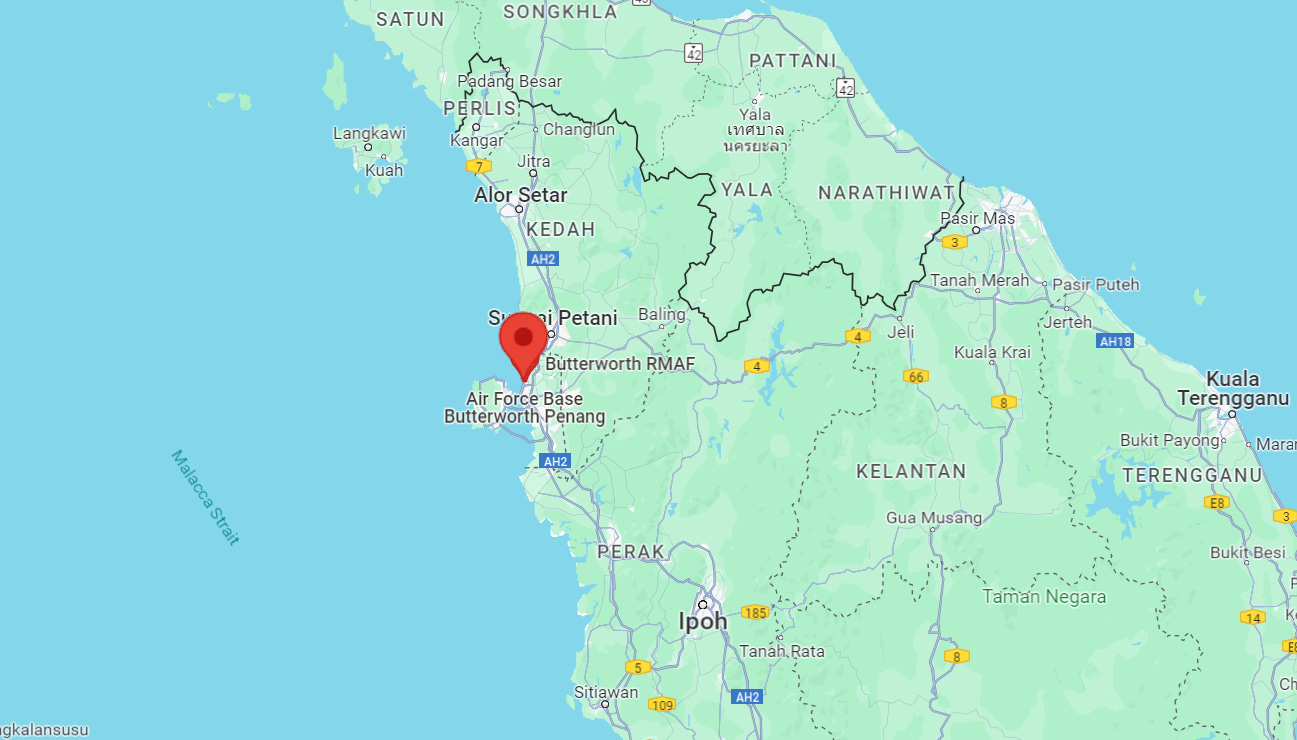

The military lost the radar signal altogether at 02:03:09. At 02:22:12 it re-established contact and registered yet another course change, this time to heading 285°, which positioned the plane back into a northwest direction. This put the aircraft around 195 nm west-northwest of Butterworth Air Force Base, located on the western shore of Penang (p. 4).

Source: Google maps

At 02:03:48, KLC received information from Malaysia Airlines operations that MH-370 was in Cambodian airspace, and relayed that to Vietnamese controllers. HCM controllers replied that they had still established no radio or radar contact. To reach Cambodian space, MH-370 necessarily would have had to pass through Vietnamese airspace (p. 243).

KLC Control spoke with Malaysia Air operations again at 02:15; the latter told KLC that they were able to connect with MH-370’s Flight Explorer (p. 299), which showed MH-370 near Cambodia. It was not until an hour later, at 03:30, that Malaysia Air operations realized that Flight Explorer provided flight projection information, not real-time aircraft positioning. In other words, the program only showed where MH-370 should be, not where it actually was.

This sequence of events illustrates the profound confusion happening among civil authorities throughout the entire time immediately following MH-370’s disappearance. Exchanges between HCM and KLC continued until 05:30 when search and rescue teams were finally activated (p. 300).

Meanwhile, the Malaysian military continued to track MH-370 over the Malacca Strait until 02:22:12 at which point it was heading toward waypoint MEKAR on or near Airway N571 (p. 6). From there, the “blip” disappeared once and for all.

Because the flight did not violate military airspace protocols, neither the Thai nor Malaysian militaries took any action other than to monitor the flight. Furthermore, military authorities do not receive records of civilian flights in most cases, so they had no way to know whether MH-370 was following an authorized flight path. As long as the aircraft did not trigger any of their defensive protocols, they essentially ignored it.

Source: Final Report

A Working Theory

In my view, there is one definitive conclusion we can draw from the evidence outlined above—either Captain Shah or co-pilot Hamid—or both—purposefully disabled the aircraft’s detection systems and then flew the Triple-7 on an unauthorized route. While I believe Shah alone is the likeliest culprit, there are a few reasons that prevent saying so with certitude. Note that what follows is a theory based on the evidence, but cannot yet be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

It does seem conclusive that no other person besides the pilots could have managed to take control of the flight. The disabling of the transponder occurred almost instantly after Shah’s last transmission on the radio. His voice revealed no major distress and no one transmitted a hijack or other emergency code on the transponder.

Cockpits are protected by reinforced doors, so a terrorist could not force his way in before one of the pilots could have sent the emergency transponder code or warned ATC on the radio. Even if somehow one or more did break in quickly enough, Shah was a highly experienced pilot. That he could not notify someone of the emergency in some subtle way defies imagination. Taking the simple action of pushing the “ident” button would have alerted authorities to some problem, but no one ever did even that.

While a terrorist scenario can, in my opinion, be essentially ruled out, the question is whether one or both pilots perpetrated the plot. I believe only one did, but the other option—that both pilots were involved—is not impossible.

The main reason this was probably a lone-wolf operation and not a flight crew conspiracy is because after ten years of investigating—by officials, journalists, and internet sleuths—no one has uncovered any evidence to support the notion of a wider plot beyond anything but rank speculation. Note that I do not use the term ‘internet sleuth’ in a pejorative way; many enduring mysteries have been solved by people adept at utilizing the full power of the web to unlock secrets.

MH-370 crashed that morning, proven by the pieces of it that have washed ashore on and around Africa. No one has taken credit (as terrorists typically do), and nothing credible has surfaced indicating why the plane “needed” to disappear or who would benefit from it. Unless someone finds new information, the logical conclusion from the data we have so far is that one—or both—of the pilots took the flight for an extended ride before finally smashing it into the ocean, probably on a personal suicide mission. The odds of a joint mission in which both pilots wished to commit a major murder-suicide are so extremely long that such a scenario can reasonably be discarded.

I am open to counter-theories on this point, of course.

So, what do we know?

Well, we know the oxygen was topped off the day before the incident. While it is true that the top-off could have been the result of routine maintenance because there was free time to do it, it is hard to ignore the timing. The report suggests that investigators looked more at the process than the reason behind it.

It does not identify whether they even asked if someone specifically requested the refill. If they had, and one of the pilots made the request, I would argue that this provides a strong clue toward the identification of the perpetrator of the disappearance. Having sufficient oxygen for the flight deck would make a lot of sense if a single pilot planned to hijack his own aircraft.

This issue is also not without controversy. An alleged, but unnamed, “former AAIB investigator” told the New Straits Times that the idea that someone on the flight crew called for more oxygen is “scandalous.” He said, “The oxygen servicing was a routine engineering maintenance requirement. This is a normal task on Boeing and Airbus aircraft.”

This unnamed individual further claimed that investigators “spoke to the engineers who serviced the aircraft and they confirmed the oxygen quantity was low.” The evidence suggests we can discount this anonymous statement, however, for the final report explicitly stated that the oxygen was not low. In fact, it was about 800 psi above the minimum (p. 47).

Because logic dictates it is extremely improbable that both pilots would have been involved in this scheme, the unwitting pilot would have presented a substantial threat to its success, making the refill of the oxygen the day before the incident more noteworthy.

Airline protocols require that at least two operators be on the flight deck at all times, except perhaps for brief breaks. The various actions taken, as outlined throughout this article, could not have been committed by one pilot without the knowledge of the other if both remained in their seats. Flight decks simply aren’t all that big.

Even if, for example, one could quietly turn off the transponder, disabling the autopilot causes a noticeable audible chime. At the point of the turn near the IGARI waypoint, we know the pilot flying needed to turn off the autopilot. In doing so, the culprit could no longer keep his activities secret. Not to mention, someone sitting on the flight deck would definitely have noticed the sharp banking turn.

Despite Hamid’s inferior position in the company hierarchy compared with Shah, he definitely would have become increasingly concerned by the various breaches of protocol and the turn onto such a peculiar route. He may have stayed respectfully quiet at first, but certainly not forever. Flying in the literal and figurative dark, against a number of international rules, was not going to help his career any more than Shah could hurt it.

If the pilots were not in on the scheme together, how did the single offending pilot manage to pull it off then? There are only two possibilities.

One would have been for the plotter to physically assault the unsuspecting pilot to the point of incapacitation right there in the cockpit. While arguably possible, the arrangement of the Triple-7’s flight deck would make this rather difficult, especially without dramatically upsetting the aircraft. Unlike in movies, it is not easy to strike a single blow and knock a person out.

This flight crew passed through security, so the criminal pilot could not easily carry an efficient weapon like a gun or blade aboard with him. Any ensuing struggle would probably have occurred with both pilots still seated, their arms and legs very near the controls. Dramatic inputs to the flight controls will disable the autopilot, so had the two actually fought, the plane almost certainly would have engaged in some wild maneuvers apparent to anyone with a radar screen. (Imagine a fight scene where bodies are pushed against the yoke). Thus, I can say with confidence that this scenario is highly implausible.

The other possibility, then, was that one of the pilots convinced the other to leave the flight deck for some reason. A trip to the bathroom by the unwitting pilot would have been an extremely lucky break for the culprit because at the time someone shut off the transponder, the plane had only been airborne for about 40 minutes. And the precision of the timing of when to turn off the transponder greatly mattered in successfully carrying out the plan.

Instead, the offender probably had to persuade the other pilot to depart on some pretext. While it is difficult to guess what that might have been, Captain Shah would have been the one with greater ability to do it.

Malaysian airlines, like many around the world, operate under an unspoken hierarchy in the cockpit. Someone of Shah’s stature would command extraordinary authority and deference on any flight, but especially one in which the co-pilot was only just hoping to elevate to a first officer position. If Shah told Hamid to go grab him a coffee, for example, Hamid would do it with no questions asked.

The reason I cannot fully rule out that Hamid is the villain here is because it is possible, if less likely, that he might have imagined up his own ruse to convince Captain Shah to exit the flight deck. By all accounts, the flight proceeded smoothly from departure to the point of its U-turn, so if Hamid came up with a good enough reason to convince Shah into going to the back, nothing specific would have prevented him from doing so.

As I will discuss in another piece, Shah may have had some proclivities toward enjoying the finer features of female flight attendants. If Hamid knew this, he could have used that as leverage to convince the Captain to leave. Still, I find this far less convincing than that Shah executed this scheme, as you will see below.

Hamid started the flight as the pilot flying, meaning he had command of the controls of the aircraft. Shah, on the other hand, managed the radio. If Shah intended to dismiss Hamid, commencing the flight in control of the radio ensured that he could properly assuage ATC right until the moment of his planned execution. At that instant, he simply would have told Hamid to hand over the controls and then go to the back for whatever reason.

If Hamid was the culprit, he only needed to fly the plane as required until he could persuade Shah to leave. The radio communications to that point would not have interfered with his plan. BUT, the radio communications themselves, seem to defeat this possibility.

Let’s return to Shah as the perpetrator and assume he ordered Hamid out for some reason. Once gone, Shah could lock him out completely because since 9/11, all flight decks are secured by virtually impenetrable doors to prevent hijackings. While pilots have a code to open the cockpit door, the person on the flight deck can override it with a lock switch located near the flight controls.

Moreover, a camera mounted above the door allows anyone on the flight deck to watch whatever is happening on the other side of the door. Shah could have watched Hamid move to the back to conduct whatever errand Shah sent him on, then activate the override lock once Hamid was far enough away.

So, what about the oxygen?

Although Hamid might be preoccupied for some time doing whatever Shah asked him to do, he eventually would return. If Shah’s scheme involved continuing the flight for a long duration, which we know the plane did, he needed to somehow remove any attempt to thwart his plan. This not only included stopping anyone from trying to enter the cockpit, specifically Hamid, but also from communicating with the ground. After all, there were 238 people in the cabin behind Shah, most or all possessing cellular phones. Even though acquiring a signal at altitude is often difficult, it is not wholly impossible.

Perhaps Shah had requested the topping off of the oxygen because he knew he planned to depressurize the aircraft. Commercial planes employ pressurization because the human body cannot process very low pressure air. As one ascends into the atmosphere, the distance between molecules decreases, thereby reducing the pressure of the air and the body’s ability to extract oxygen from it.

At altitudes above 10,000 feet or so, humans start to become hypoxic. At first, hypoxemia manifests as confusion or physical disorientation, but eventually it leads to unconsciousness and then death. Depressurizing the Triple-7 is an all-or-none affair. One cannot depressurize the cabin where the passengers sit and not the flight deck.

So, knowing he would face a depressurized flight deck, but still wishing to be capable of maintaining flight, Shah could have requested the top-off to ensure his mask would provide him enough breathable air for many hours of operation. Oxygen for the drop-down masks for passengers and supplementary supplies for the cabin crew come from different sources than that of the flight deck.

If he kept the plane depressurized at altitude long enough, everyone in back would die, but that could take a while as the drop-down masks provide air for 15-20 minutes, and the cabin crew had supplemental oxygen for quite a bit longer than that. Furthermore, as Helios Flight 522 proved, some people can survive for an extremely long time even at 34,000 feet without any supplemental oxygen. Shah would have known he needed to prepare for a lengthy duration without breathable air.

The theory that Shah intended to kill everyone by oxygen depravation is supported by the timing and nature of his radio traffic, and the trajectory and location of the plane at the time of execution of the scheme. (This is also why I think it very improbable that Hamid could have been the culprit).

At 00:46:39, MH-370 switched from Departure control to KLC regional control (p. 2). Shah acknowledged the switch with a response employing the appropriate protocols. Roughly four minutes later, he received permission to ascend to 35,000 feet, which he also properly acknowledged.

Around that time, or very shortly thereafter, MH-370 would have risen above 10,000 feet, the approximate altitude where people start to feel the effects of oxygen depravation. By 00:57, the flight would have exceeded 30,000 feet. Remember that by now, Shah would already have sent Hamid away.

Sometime between 00:50 and 00:57, Shah commenced the depressurization process. The controls to do this sat above and to his right on the top panel. Clicking over to manual, he could set the pressure to the same as the outside air, rendering virtually everyone who lacked supplemental oxygen unconscious in mere minutes. As soon as the pressure started to drop, the yellow cup-shaped masks would automatically drop down to passengers in the back, so he had no way to conduct this part of the plan secretly.

Nevertheless, neither the cabin crew nor Hamid would know at that time that the masks fell because of an intentional act. They would assume instead that some kind of mechanical malfunction occurred; while rare, this does happen from time to time on commercial flights. Hamid would surely try to reenter or call the cockpit from the purser’s phone, both to no avail as Shah would ignore him. At least for a bit, Hamid would probably assume Shah was engrossed with trying to resolve whatever presumably went wrong. Hamid may have busied himself with finding his own oxygen source while he waited for Shah to open the door.

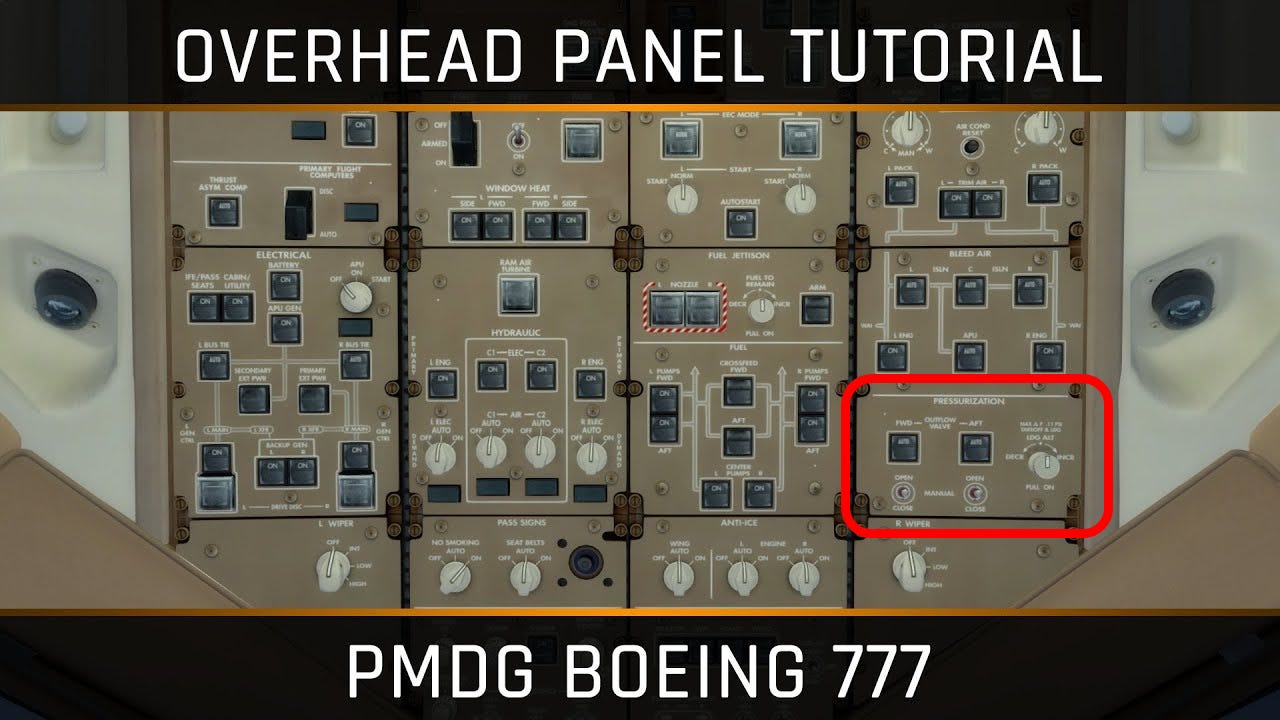

Triple-7 pressurization switches; Source: Doofer911 (YouTube).

As Shah initiated the depressurization of the aircraft, donned his own oxygen mask, and watched the door’s camera monitor to see how people reacted in the cabin, he may have been distracted. This would explain his unnecessary repeat of MH-370’s altitude to Air Traffic Control, as noted above.

MH-370’s location at this moment would have helped Shah conduct his plan in secrecy, at least to the outside world. By this point, the flight approached 35,000 feet and was well over 50 miles (80.4 km) from the nearest shore. There, capturing cell service was as close to impossible as it was going to get. Thus, for now, Shah need not worry much about anyone in the back successfully relaying their situation to anyone outside the aircraft. By the time they could, he undoubtedly hoped, no one would be left to try.

Next, Shah needed to make MH-370 go dark on radar. He conducted the necessary radio contacts, saying goodbye to KLC at 01:19:30 (p. 2). Shortly after he let go of the mic key, he reached down and to his right and switched the transponder to standby. To ensure that the backup system did not transmit to ground operations, he also needed to pull the busses.

While I could not find their exact location in the cockpit, the bus panels are located behind the pilot chairs. This would have required Shah to exit his chair for a moment. Indeed, the final radar blip on ATC’s display disappeared about one minute after Shah switched off the transponder, a sign that he did in fact get up and pull the busses.

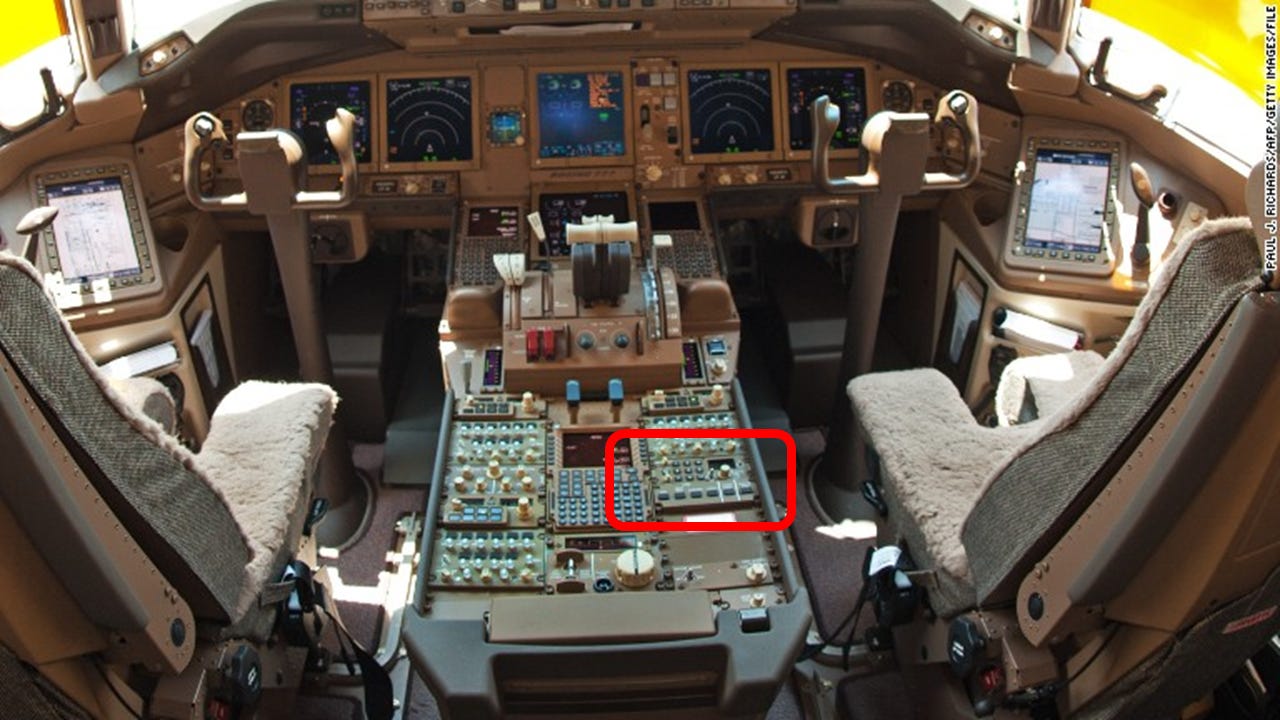

Triple-7 cockpit with transponder circled. Source: CNN

Having flown this route numerous times before, Shah knew approximately how much time he had until the Vietnamese controllers might start looking for him. He would also have known the relative informality with which nighttime flight operations are handled. So, he reentered the captain’s chair, switched off the autopilot, and conducted a gradual right bank.

In the back, few if anyone would notice this because without external visual cues, humans are objectively bad at detecting even modest changes in an airplane’s flight. And MH-370 was in the darkness over the sea. Shah needed to perform this right turn to give him sufficient room to conduct the subsequent full U-turn in a leftward direction without breaching the Thai military defense airspace. Once the plane reached the right spot, he steered it sharply left.

Whether anyone in the back could have noticed the second banked turn is hard to say. According to radar data, the turn was not exceptionally smooth and reached a sharp bank-angle, but detecting it from inside would nonetheless be challenging. If anyone, perhaps Hamid did, but by now nearly everyone in back was nearing or at the end of their supplemental oxygen. Many would feel the onslaught of confusion, but be incapable of understanding why. The less healthy might succumb to unconsciousness quite quickly, and some would even feel a sort of “manic high” often associated with diminished oxygen.

Even if Hamid did not yet feel these effects, there was little he could do about what the plane was doing. Meanwhile, comfortably settled in his mask, with a locked and fortified door securing him, Shah might have glanced at the camera on occasion to witness the increasing malaise behind him, and it would have satisfied him enough to focus on flying.

In fact, he needed to center his attention intently on flying to continue to evade detection. To keep from stirring up trouble from the military, he had to make sure the aircraft steered abundantly clear of military airspace. Shah also wanted to avoid detection from other civilian jetliners. Turning off the transponder, and thereby the TCAS, essentially rendered MH-370 invisible to other planes, but it also cloaked them from Shah’s view. For this reason, he followed a track parallel to one of the designated aerial lanes so he could maintain his bearings. This would prevent him from getting lost, but also situate him far enough from inadvertently coming too close to another jet.

Furthermore, Michael Exner’s analysis suggests Shah climbed to 43,000 feet. Well above the typically authorized flight level for planes in this area, Shah knew that flying there all but assured he would not be spotted by other pilots. While that altitude was rather high for civilian aircraft, it was not so high that the military might mistake him for a spy plane. The Triple-7 also could handle it, even though such an altitude neared its maximum ceiling.

The subsequent path taken by MH-370 further lends credence to the notion that Shah, not Hamid, piloted the aircraft. At 01:52:31, it passed near to Penang Island, where Shah’s hometown was located (p. 4). Perhaps this flyby was his last goodbye.

Bandar Baru Farlim Penang’s LBS detected Hamid’s phone around this time, but the telecom believed it would not have been able to do so had the plane been much higher than 20,000 feet. While this detection may have been the result of random atmospheric conditions and thus occurred above 40,000 feet, it could also be possible that Shah temporarily dipped the plane to get a final closer look. Whatever the case, from there Shah directed the flight toward the open ocean where he would ultimately turn southward.

At 02:22:12, the Malaysian military saw MH-370 for the last time on radar over the Malacca Strait (p. 4). Whatever the plan or the motivation behind it, this constituted an essential point of no return. Soon, MH-370 would enter an oceanic no-man’s land, a place so remote that reaching a positive outcome would near, and then become, an impossibility. Captain Shah, if indeed the culprit, must have at that time prepared himself to die. The other 238 people aboard were, by then, probably already gone—dead from the starvation of oxygen.

* * *

The ACARS Problem

At 02:03, ground control attempted to contact the flight’s ACARS system, but received repeated failures for forty minutes straight. There is a great deal of confusion about how one goes about powering down the ACARS. That it would come back online later, only adds to it. In the scenario outlined above, however, there are some explanations for how (if not why) the ACARS could have been non-responsive that would not derail the theory.

Entering into this discussion here would complicate matters unnecessarily. After all, even if Shah needed to exit the flight deck to disable the ACARS, as some have suggested, the people in back would have been without oxygen for over an hour by then, rendering them all deceased or at least inert. Moreover, the how in this instance is less important than the question of why one would turn it off and back on (if indeed that happened). So it makes sense to leave that discussion for another piece.

A Note About ATC

Many conspiracy theories have traversed the interwebs about MH-370. Some have looked to governments themselves as the conspirators. In particular, many question the apparent weirdness involving the actions of the controllers. I have flown in that part of the world and have studied air traffic incidents there as well. ICAO, the International Civil Aviation Organization, sets the standards for how ATCs across the globe operate to try to ensure standardization and, ultimately, safety. But rules are made to be broken, and familiarity breeds mistake.

Many air traffic corridors see far lower volumes of traffic at night, especially in areas outside of closely-packed, large metropolises. MH-370 traveled an area precisely like this. The flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing was one of only a handful passing through that area, as was the case on most nights. These nightshifts often saw the same flight crews and controllers, which led to a rather informal attitude among them.

Ho Chi Minh’s controllers may have acted negligently, but that is probably because they had done so numerous nights before without incident. The same can likely be said of many of the region’s pilots. Only upon realizing that in this instance their negligence may have contributed to catastrophe did the HCM controllers make some feeble attempt to hide it. This hints far less at a conspiracy related to the incident itself, and more toward their realization of the result of their casual attitude toward a very serious job.

ATC’s ineptitude and the subsequently delayed search for the plane may be anger-inducing, but the reality is that neither probably made any difference toward the outcome. Shah, or whoever piloted the aircraft, took significant and skilled measures to avoid detection. Even if both KLC and HCM controllers did their job with militant and expert efficiency, hours would have passed before the search ever neared the right place.

In fact, given that MH-370 flew for many hours after turning off the transponder and going dark, it is hard to imagine a scenario where the search effort could have been more properly targeted in the early hours of the incident. Even today, a decade later, no one knows precisely where a “properly targeted” search should be commenced.

Air Traffic Controllers feel a responsibility for flights that is hard to comprehend for outsiders. Listen to any recording of aircraft crash incidents to hear the horror in the voices of controllers when the flights they oversee disappear. Those individuals know that, whether they could have prevented it or not, the crash that occurred on their watch probably just killed hundreds of innocent people.

I do not excuse controllers for treating their role with laziness or informality, but I also do not think it useful or fair to attack them for their ostensible bungling here. I do not know what happened to these controllers since, but I know in other cases some controllers have committed suicide because of outcomes for which they felt some responsibility. In the case of MH-370, someone caused this tragedy, but that person sat on the flight deck, not in a radar tower. Give the controllers at least a little sympathy.

Finally

That MH-370 flew under the direction of a human hand is without doubt. Likewise, the path of the plane up until 02:22:12 is without question (*assuming the investigative report is true, a matter I will address in other articles). So we are only left with two questions, really: 1) Where did MH-370 ultimately end up? And, 2) Why?

Several pieces of debris have washed ashore on the western end of the Indian ocean that ostensibly belonged to the aircraft. Examinations of the items, their location of discovery, and the probable mechanisms (i.e. ocean currents) for how they arrived there will reveal the location of the main body of the aircraft one day, I suspect. Finding it will answer the questions about where MH-370 went after 02:22, and the manner by which it reached its final resting place.

Sadly, I do not think these discoveries, if ever made, will answer the question of why. Unless whoever flew the aircraft made an oral confession in the moments before impact, and it was successfully captured on the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and is still able to be recovered for investigators to listen to it, the black boxes will probably tell us only what happened to the plane itself (and perhaps the passengers within).

That is not to say that they won’t provide useful clues. For example, the flight data recorder (FDR) will show which side of the cockpit controlled the flight. This may provide us a better chance at definitively zeroing in on Shah or Hamid as the perpetrator. Other data might add some context to the investigations already conducted into both of them.

Otherwise, what needs to be done is the fullest possible inquiry into each of these pilots in the days, months, or even years leading up to the event. To date, many remain skeptical that Malaysian authorities have done a decent job in this regard. Or, if they have, the public needs to know what they uncovered.

It has been over ten years since the incident and families still want answers. To hold back information is, at this point, an insult to those families. That said, we do not know if the authorities are in fact holding back, or if what they have released is simply all there is. And that is why these types of cases are so vexing.

Whether investigative authorities have been forthcoming or not, a lot of information is available in the public sphere. I have uncovered some myself that does not seem to have made a significant splash in the media, but nonetheless has some value. In my next pieces on this topic, I will share what data there is with you and offer my input on whether we can surmise at least a possible motive and, perhaps more importantly, if we can discern some new leads to consider.

Update: The approved flight level was erroneously given as 37,000 feet (FL370) in the first publication of this article. It should have been 35,000 (FL350). This was probably a mix-up based on the name of the flight (MH-370), but was entirely my error. Apologies!

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement.

Visit the new Evidence Files Law and Politics Deep Dive on Medium, or check out the Evidence Files Facebook; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

To read another detailed breakdown of an air crash incident, this one involving Yeti Airlines Flight 691 in Nepal, examined over two articles, click below. If you love aviation, consider visiting Petter Hörnfeldt’s Mentour Pilot YouTube channel here.

Way back when this happened there was some kind of article that said there was a bunch of scientists on board and some country had a taken down because of whatever work they were doing or wanted them silenced or at least one of them so they took down the whole plane. This was extra long read I just finished it read half of it the other day second half today but your reasoning makes me ponder 🤔