Information in this story comes directly from the final report (original version available in French only) produced by the Moroccan Bureau d’Enquêtes et Analyses (BEA), unless otherwise indicated.

Gross negligence led to a commercial aircraft performing a feat that maybe none has ever done before, and through sheer luck did not kill anyone aboard. This story shows how selfishness, a disregard for the rules, and a culture of indifference nearly led to catastrophe. But it also shows how the science and engineering in the aviation industry, perhaps unparalleled in any other commercial enterprise, has evolved into the safest form of transportation in the world. Here is the story of Air Maroc Express 439.

On July 9, 2018, Air Maroc Express 439 prepared for takeoff from Tangier to Al Hoceima in Morocco, designated as flight RAM439. Air Maroc Express operates as a subsidiary of Royal Air Maroc performing domestic flights across Morocco, in this case flying from Tangier Ibn Battouta Airport (ICAO: GMTT) to Cherif Al Idrissi Airport (ICAO: GMTA). This flight, conducted in an ATR 72-600, was commanded by a 61-year-old Training Captain who had a total of 13,487 flight hours but only 139 hours on the type, having received his rating just four months prior to the incident. This means that despite his extensive experience, he was virtually brand new to the ATR. Before his time on the ATR, the captain had spent many years flying Boeing 737s. His first officer had just 1,063 flying hours, but most of them (815) were on the ATR. He had begun his career with Air Maroc Express just two months prior, and was 25-years-old. In addition to the two pilots, a brand-new recruit who was not yet qualified to fly, sat on the flight deck. Altogether, the aircraft contained 58 people.

Source: Skybrary

The incident flight that day was the third of a series of legs that expected to start and end in Casablanca. On the first leg, Casablanca to Al Hoceima, the captain acted as the Pilot Flying while the first officer monitored the instruments. An unexpected alert happened on this flight that would directly contribute to the incident later. While cruising at 16,000 feet, the Enhanced Ground Proximity Warning System (EGPWS) sounded along with a visual alert indicating “terrain fault.” The purpose of this system is to alert flight crews of an impending collision with terrain, usually a mountain or the ground if the aircraft descends too rapidly. In this instance, the alert didn’t make sense considering the nearby terrain was largely flat and they were several miles above the ground. The final report suggested that the error may have been “linked to a degradation of the GPS signal,” and the pilots probably felt confident in ignoring it since they could see that they flew near no problematic terrain. The fault disappeared before they began their descent.

As they approached Al Hoceima, the clear skies gave way to patchy fog. Commercial flights preparing for landing in reduced visibility conditions almost always opt for an instrument-led approach. For this landing, they intended to conduct a non-precision RNAV approach to runway 17. RNAV (standing for aRea NAVigation) uses GPS to provide pilots a flexible path between two navigation points. It is considered “non-precise” because it gives positional information, but does not provide altitude guidance. Flight RAM439 faced a cloud ceiling of 800 feet, while the Minimum Decision Altitude (MDA) was 1,030 feet. The MDA is a “specified altitude or height in a Non-Precision Approach (which, RNAV is one) below which descent must not be made without the required visual reference.” This meant that if the captain could not see the runway once he descended to 1,030 feet, he should not descend any further. Yet, the cloud cover extended below that threshold indicating that he would probably not visually acquire the runway. As such, he should have planned to deviate to another airport. As you will see, he did not.

Source: Google Maps

When the flight reached 1,030 feet—the MDA—the cockpit voice recorder picked up the captain stating that he could not see the runway. Nevertheless, he continued the descent, and at a relatively rapid rate of 1,000 feet per minute (fpm). The FAA has limited the descent rate to 1,000 fpm on instrument approaches. This is because at a higher rate, humans have difficulty ascertaining speed and positioning. Here, the pilot operated on a non-precision approach, unable to see either the runway or the ground, and descended at the maximum allowable rate against the clear restrictions of the Minimum Decision Altitude. Unsurprisingly, the EGPWS sounded again shrieking, “terrain ahead, pull up!” The terrain it detected was the Mediterranean Sea. The captain responded immediately, adding power and pitching the plane upward. When he did so, the sea swirled just 45 feet below. Luckily, the ATR managed to acquire altitude, and the flight eventually landed without further issue. Despite a requirement to do so, neither the captain nor first officer reported the incident. The second leg proceeded normally from Al Hoceima to Tangier, as if nothing had happened on the first.

For the third leg, the return from Tangier to Al Hoceima, the first officer assumed the controls. While on the ground preparing for takeoff, the captain advised the first officer of their plan for the approach into Al Hoceima as follows:

If the runway is not in sight at the MDA, we will descend until a height of 400 feet which will then be maintained until the runway is in view and that if the runway is still not in sight at 2 nm from the VOR, it will be necessary stop the approach and make a go around.

Advising the first officer to descend beneath the MDA clearly violated the rules. The MDA is set purposely by authorities to ensure a safe approach in the event outside conditions do not allow the flight crew to see potential obstacles. Pilots are not permitted to simply choose their own minimum decision altitude. A “go around” means that a plane climbs back into the air, abandoning its landing attempt, to re-orient and try again under safer conditions. Nearly every commercial airport has an established procedure for doing so, including the height to which the aircraft should climb and the heading it should follow. This policy exists precisely so flight crews do not need to make “on the fly” decisions when things go awry on approach. At most airports, performing a go around is as routine as any operation. It becomes less routine, however, when flight crews abandon other policies leading up to it.

To make matters worse, the first officer proposed disabling the EGPWS—the system that warns of an impending crash into terrain—because of its erroneous alert on the earlier leg. After consulting the Dispatch Deviation Manual (DDM), otherwise known as the Minimum Equipment List (MEL), the captain agreed. He should not have. The minimum equipment list allows aircraft to operate with minor malfunctions that do not affect the ability to conduct a safe flight. While the EGPWS did issue an erroneous alert at altitude, it also functioned as it was supposed to when the captain came perilously close to the sea on the first leg. Choosing to purposely disable the system suggests a desire to avoid annoying alerts during a time the flight crew intended to violate proper flight procedures. This decision would have a considerable impact on what happened a short time later.

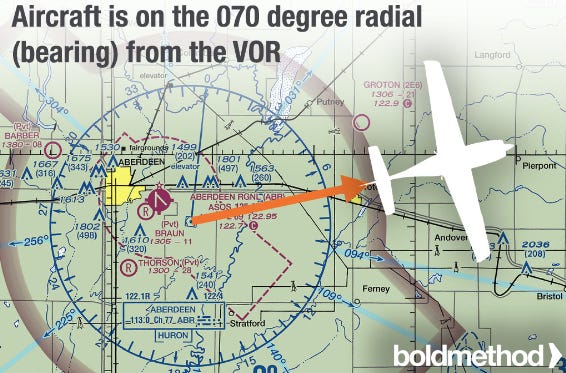

For the approach into Al Hoceima, the pilots planned to perform a VHF Omni Directional Range Radio (VOR) approach. Also a non-precision approach, the VOR is a ground-based radio transmitter that determines an aircraft’s bearing from the VOR transmitter. As mentioned, a non-precision approach provides the pilots no guidance on the aircraft’s height above the surface. Thus, VOR approaches also have a set Minimum Decision Altitude under which pilots should not descend until visually acquiring the runway. On this leg, the MDA was set at 760 feet. As he stated in his briefing to the first officer, however, the captain already anticipated descending below it to 400 feet irrespective of the external conditions.

RAM439’s flight back to Al Hoceima was a very short one, spending just six minutes at cruising altitude. During the trip, the captain told the first officer that on approach, he would monitor the speed “and water” while the first officer operated the controls. Air Traffic Control (ATC) cleared the aircraft to begin its descent, with an expected approach again onto runway 17. As they descended below 5,000 feet, the captain disabled the EGPWS as he and the co-pilot discussed earlier. During the descent, ATC advised of a cloud ceiling at around 600 feet, below the minimum decision altitude, but above the captain’s intended deviation. This likely compelled him to continue the descent as planned and, indeed, he immediately thereafter set the autopilot to level off at 400 feet. Upon reaching 2,500 feet, the aircraft’s approach speed exceeded the norm by 80 knots, adding to the dangerous situation. Regardless of all these issues, the crew extended the landing gear. Upon doing so, the captain said “go, go to the limit,” at which time the aircraft’s descent increased to an astounding 1,800 fpm. In a short time, the plane reached the set altitude of 400 feet, but the crew could not see the runway. Rather than rectifying the situation by proceeding to go around as he had suggested in his briefing with the first officer, the captain instead ordered “we continue to 300 [feet].” When they neared 300 feet and still could not find the runway, the captain announced “keep on going” and the flight continued down to just 135 feet above the water.

At this time, the first officer proclaimed, “it’s not normal.” Surely, he meant everything about this approach, or at least specifically about the dangerously low altitude at which they flew. Switching to his native language, Arabic, he stated that he was disabling the autopilot; by that point the plane flew a mere 80 feet above the sea. The first officer’s switch to his native tongue likely indicated his increasing level of stress. Despite his limited experience, he must have known that flying blind as they were at such a low altitude could not be safe. Sure enough, as soon as he switched off the autopilot, he began pulling back on the stick to bring the aircraft up while simultaneously increasing power. At the same time, and entirely inexplicably, the captain began pushing down on the controls, which effectively neutralized the first officer’s efforts. Pushing with greater force than the first officer, the captain then led the aircraft downward even further until, suddenly, the ATR slammed into the sea with an impact of 3.2 g-forces, followed quickly by a second hit reaching 3.9 g-forces. After the second impact, the captain let go of his control column while exclaiming “oh shit!” causing the flight to ascend as the first officer continued pulling back, now likely in terror. They had effectively just skipped the ATR off the sea like a rock thrown across a creek’s surface! Upon their (miraculous/lucky) recovery, the captain advised ATC that they were performing a go around. He claimed that they had just encountered a bird strike and that they preferred to re-route to Nador Airport. ATC of course cleared the flight’s request and it eventually landed there without further difficulties.

Although it is understandable that the captain wished to hide his malfeasance, it is not clear how he expected the “bird strike” story to hold up. The ATR struck the water twice at speeds in excess of 120 knots and only by some miracle did not crash. Nevertheless, commercial airliners are not made to casually withstand water impacts. Even the famous “Miracle on the Hudson” Airbus A320, which may have made the smoothest commercial aircraft water landing of all time, saw one of its enormous General Electric CFM56 engines ripped from the wing upon impact. While the Air Maroc ATR may have only “skipped” across the surface, it did so with significant force. And the damage was indeed severe.

Image showing damage to the undercarriage of the fuselage (from the official report).

As the photo illustrates, a huge chunk of the underneath of the plane ripped apart. In addition, all three sets of landing gears sustained considerable damage. Bird strikes cannot cause either of these scenarios, and a noticeable absence of avian blood and guts further eviscerated the captain’s story. Remarkably, the ATR landed at Nador without causing any injury to the crew or passengers, despite this heavy damage. This is, perhaps, a testament to the sturdiness of the ATR, and partially explains its extraordinary safety record.

This time, the incident could not go unreported. After all, 50-some passengers just watched their aircraft bounce off of the water. Moreover, birdstrike reports to ATC are routinely investigated to check for damage to the aircraft. Thus, once the passengers deboarded, the Moroccan Bureau d’Enquêtes et Analyses (BEA) immediately commenced an inspection of the plane and investigation of the events. In the dry language of investigative reports, the BEA concluded the probable cause of this accident as:

Non-compliance with operational procedures, in particular; the deliberate deactivating of the EGPWS, the continuation of an unstable approach below the applicable stabilisation gate and the continuation of the approach below the applicable minima in the absence of visual reference with only the First Officer’s reaction, even though it was late, making it possible to limit the outcome to no more than significant damage to the aircraft.

Among the recommendations made in the report, many emphasize training. This appears to whitewash the true cause here, however. While some might argue that the flight crew gradient— the power disparity between the pilot and co-pilot based on age, rank, or other factors—played a part in the first officer’s actions, no such latitude should be extended to the captain. Considerably experienced in operational protocols, the captain could offer no plausible explanation for his repeated disregard for safety procedures. Instead, the progression of events that day suggested that this captain routinely “did whatever he wanted” despite the conditions or rules. Sadly, the final report makes no mention of any disciplinary action and does not even name the members of the flight crew. Whether either member of this crew suffered any professional consequences is unknown. Air Maroc Express seems to have attempted to cover up a past incident in Germany in 2016, so maybe the captain’s attitude toward safety simply reflected the culture of that airline. Regardless, 58 people have little more than luck to thank for their lives.

In most aviation incidents, the goal is not to impugn the pilots but to uncover problems and correct them with a mind toward improving safety across the industry. The case of Air Maroc 493, however, was somewhat different. Here, the captain was unequivocally culpable for what happened and, only by the grace of extraordinary fortune, no person suffered serious physical harm. At 61-years-old, and with such extensive flying experience, it seems unlikely that this captain’s cavalier disregard for safety policies and procedures can be corrected. While we do not know the outcome related to his future in the profession, if the authorities did not revoke his license, that is a strong indicator that safety is not taken seriously. At 25-years-old, and operating in the scenario of a junior pilot subject to the whims of a vastly more experienced captain, there seems room to rehabilitate the first officer.

In any case, this incident represents an aberration. Flying is extremely safe, perhaps exponentially safer than driving in a car. I only wrote about this story to show how even in the face of gross negligence, the ATR withstood incredible abuse and brought its passengers home safely. The technical and engineering prowess of the aviation industry is, in my opinion, second to none. Thanks for reading!

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, Digital Forensics, and Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I conduct research in all of these, and run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my non-profit’s page here.

For more on accident flights see:

The Tara Air Flight 197 Final Report

I previously wrote on this incident based on the release of the preliminary report. Nepal’s Civil Aviation Authority (CAAN) has now released its final report on the incident. This article will reference my previous, but with new detail and recommendations based on the latest findings.

Analyzing Yeti Airlines Flight 691

The preliminary report regarding Yeti Airlines Flight 691, which crashed in Pokhara, Nepal on January 15, 2023, has finally been released by the Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission of Nepal’s Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation. Occurring on a clear, sunny day, the flight crashed just between the runway of the old regional airport and…

For a remarkable feat of aviation, another case where no one died, see:

A Legendary Performance

Except as noted, all information in this article comes from the Final Report of the Board of Inquiry, of October 12, 1983. Air Canada Boeing 767-200 On July 23, 1983, one of the most remarkable events in the history of aviation occurred involving Air Canada Flight 143. Flying a