The idealization of the past has direct implications on the present. Deeply held beliefs about a polity’s origins, particularly focused on the alleged nature of its founders or key historical leaders, permeates its law, politics, and social fabric. Too often, these beliefs are built on myths, stories told to obfuscate the untoward elements of history present in every narrative of every people.

From the 20th into the 21st century, this has had a considerable impact on the lives of people in Tibet. In the mid-20th century, political figures employed vague, routinely misleading depictions of centuries’ worth of history to justify present-day military action that has devolved into long-term oppression.

Likewise, in the United States authorities frequently invoke references to the country’s organizers to accomplish specific political goals. Just as has been done with Tibet, these references tend to lack nuance, or are simplified to the point that they are misleading or entirely false.

In both cases, references to history (or revisionist history, as it were) is used to bolster agendas that typically do not benefit the populace or the nation-state as a whole. This occurs when a balanced look at the earlier events works against those agendas. Proponents turn toward invoking emotional responses where the evidence does not suit their desires. Tibet and the United States provide useful case studies for analyzing this phenomenon.

Real Tibet

Back in 2000, Orville Schell released a brilliant book called Virtual Tibet: Searching for Shangri-La from the Himalayas to Hollywood. In it, he discussed how the mystique of historical Tibet has had a profound influence on its recent trajectory.

Starting with early adventurer logs written by people like Henry Lansdell and William Rockhill, to later Hollywood productions such as Brad Pitt’s rendition of Heinrich Harrer’s time with the Dalai Lama in Seven Years in Tibet, Schell identified the many illusions about Tibet that emerged from these kinds of works and entered into the political discourse, and how those fantasies affected the now decades-long conflict.

What especially lends to the virtual view of Tibet is that an entire country and culture is personified in a single man, the 14th Dalai Lama—a modest, charismatic fellow always draped in the apparel of a monk.

His distinctness from what non-Tibetans know as ‘normal’ among leaders only strengthens the perception between the banality of Western culture and the esoteric spiritualism of Tibetan culture. Add to that his noticeable accent when speaking otherwise excellent English, along with his occasional social faux pas predicated on acute culturally accepted normative differences, and the image is complete.

Alas, the real Tibet is no more or less a Shangri-la than any other historical place, James Hilton’s depiction notwithstanding. As is the case of any people anywhere, Tibetan history is replete with violence, political intrigue, discrimination, sectarian division, and, well, all the other lousy stuff we recognize as the common threads of humanity’s historical fabric.

Even the Dalai Lama as an institution was not without its controversies. The first Dalai Lama to be named as such, Sonam Gyatso, received his title from the Mongol warlord Altan Khan, not from Tibetan oracles or officials. Gyatso technically became the Third Dalai Lama, as the previous two were identified posthumously and contemporaneously to his recognition. You can read more about those first three in a brief article I wrote here:

Following the initial three, who were widely respected monks and scholars, the fourth Dalai Lama was the first who was not of Tibetan descent. A year after Sonam Gyatso died, the great grandson of Mongol leader Altan Khan — Yonten Gyatso — was named the next reincarnation. This caused all kinds of controversy. Was this Dalai Lama legitimate? What were the Mongols up to politically? In any event, Yonten Gyatso died mysteriously at the age of 27.

The fifth Dalai Lama, often referred to as the “Great Fifth,” managed his ascension to both political and religious power quite pragmatically, and did not spare the sword in some cases. At the time of his rise, Tibet was embroiled in what could reasonably be called a civil war.

To “reunify” Tibet, as historian Matthew Kapstein has put it, the Fifth seized land and wealth from certain Buddhist sects and handed them to the Gelukpa (the sect of the Dalai Lamas). He chartered the building of many new Gelukpa monasteries, some rather ostentatious, and he did not prevent the execution of lingering loyalists from the brutal monarchy that his government ultimately supplanted.

After he died, lower-level political figures frequently battled for primacy over the years. Their conflicts led to what almost certainly were assassinations of later Dalai Lamas, some even as children. Nobles occasionally fought and killed each other, sometimes with the help of Chinese officials posted by the Qing dynasty rulers in the Tibetan capital, Lhasa.

In one case, these officials — known as the amban — orchestrated the assassination of the then-Tibetan king, Gyurmé Namgyel, in 1750, partly driven by his despotic rule (calling his governance a kingship is a complicated matter worthy of its own piece). That killing led to a brief uprising where allies of the deceased figure organized squads that murdered both amban officials and many other Chinese living in the city.

Starting in the 1800s, Central Asia endured the Great Game, an ongoing geopolitical contest between the British and Russians that left Tibetans (and Afghanis, and many others) stuck in the middle, often to disastrous consequences. This led to the Tibetans deciding to isolate themselves from the outside world for nearly a century.

Late in the 1800s, conservatives in Tibetan politics feuded with the 13th Dalai Lama, the most adept of them since the Great Fifth, about how to handle the country’s defense. Some argue that these disputes eventually made Tibet more vulnerable to outside encroachment and abuses.

The lesson to take away from all this, one wholly lost in the popular history of Tibet, is that it almost never functioned as a unified, utopian nation. The vast size, desolation, and ruggedness of the landscape effectively precluded a uniform exercise of control or influence. Physical isolation and localized politics led to a wildly diverse social sphere. Indeed, many Tibetans — perhaps sometimes the majority — did not even know the identity of the Dalai Lama, let alone whatever he may have been up to at any given time.

Using imagined history for realpolitik

To support whatever is the narrative of the moment, people tend to lionize figures and beliefs about the past while conveniently ignoring their associated flaws. Doing this diminishes the pursuit of solutions because it obfuscates real problems, replacing elements of them with facile substitutions that only serve to prop whichever side’s position.

The result of such sophistry is that debates degrade into mere power struggles, with the most aggressive or strongest faction nearly always winning, and humanity frequently losing. There’s no presentation of evidence or evaluation of the quality of ideas, just a fictive competition between factionally-driven stories.

Regarding the Tibetan dispute with China, might things have developed differently if Tibetans were characterized as real people, replete with societal blemishes, instead of fictional characters of whimsical fairy tales, when political autonomy was on the line? Perhaps.

An often asserted position in the arguments about Tibet’s status as an independent polity was that features of its “mystical” nature illustrated its historical function as a mere protectorate of the Qing dynasty, thus a part of the modern-day Chinese polity. Then again, when convenient, the opposite of the Shangri-La narrative was used to highlight the supposed feudal and oppressive character of pre-20th century Tibetan government to make the same point. International leaders seemed to accept these tales, at least insofar as to steer clear of intervening in the dispute.

A careful analysis of the documented history, however, reveals a very muddled tale, one that provides limited conclusive evidence one way or the other as to the role of the government of China in Tibet’s issues. At the least, it is clear the government in Tibet acted as all governments do—managing their own affairs while always considering the implications of their decisions’ effects on their neighbors. After all, Tibetan officials not only sought to avoid external conflict, but they realized that they were not well positioned to engage in any.

Instead, the government tended to rely on the “priest-patron” relationship, wherein Tibetans gave the world their spiritual and philosophical teachings in exchange for military assistance. This hardly speaks toward a character of subservience and more toward the decision to barter services between experts of one and the other. But the history has been twisted to support a countervailing argument.

Regardless, centuries of history should not serve as the sole — or even primary — determining factor for one people’s right to rule over another. History is routinely written by the victors, irrespective of any associated moral good or blatant evil. Employing history to permit present-day authoritarianism only invites a perpetuating cycle of it.

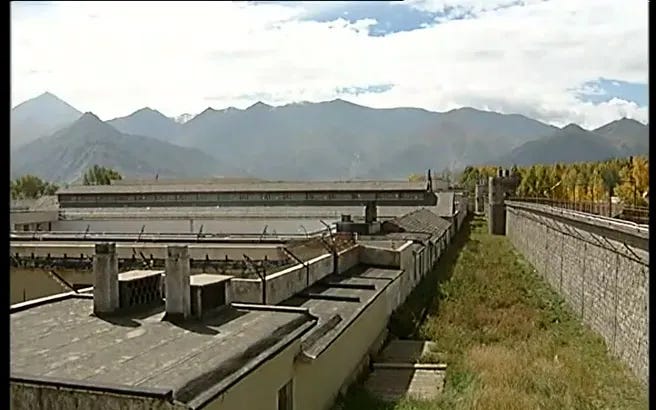

Drapchi Prison is where many Tibetans live now as a result of their ‘liberation’ that started in the 1950s. Credit: Tibet Research Project.

Realpolitik and the Founding Father mythology

In America, ruminations on the views and character of the Founders strongly influence the very fabric of the nation’s politics and law. Just as many participants in the Tibetan context strive to foist a mental construct of a place and people that lived a very different experience, so too do certain commentators in the United States.

Perhaps the most pernicious result of this historical revising is in its application to jurisprudence. Assertions about what the Founding Fathers allegedly believed often become the foundation for judicial opinions that effectively become law. There is even a name for it — originalism.

If one considers the rampant deficiencies of character among many of these revered individuals, then the question about the legitimacy of originalism’s role in modern jurisprudence becomes a poignant one. Some of the designers of the Constitution were slaveowners, for example. Is their opinion on the station of certain people in society one that should carry any legal relevance in 2024?

Disputes about the second amendment of the American Constitution provide a prime illustration of the ways in which arguers attempt to impute the supposed stance of the Founders on modern perceptions about the interpretation of specific topics of law, in this case regarding firearm ownership and the meaning of militia.

What is particularly interesting in this debate is that many participants in the feud cannot even agree on what the text of the amendment itself says. This is a direct result of the long temporal distance between the time of its writing and today that has altered the way in which the English language is used and understood.

Historian Michael Waldman aptly summed up the problem:

[T]he eloquent men who wrote ‘we the people’ and the First Amendment did us no favors in the drafting of the Second Amendment.

Rather than explore the contemporary lexical and grammatical construction in a manner like Kari Sullivan of the Duke Center for Firearms Law has to discern the probable meaning, the tendency of many today seems to be to assign whatever connotation best suits their own political purpose. Nelson Lund of George Mason University School of Law exemplified just this tactic. Lund wrote:

It is self-evident that the Second Amendment’s preambular phrase alludes to a reason for guaranteeing the right of the people to keep and bear arms. [Emphasis his]

America’s highest court, the Supreme Court, likewise adopts this tactic of reimagining the meaning of the text and then asserting that the justices’ opinion reflects the “original intent” of the Founders. In the seminal case of recent second amendment jurisprudence, the majority described its purported methodology for discerning whether a modern law fit within the directives of the language of the amendment as follows:

It’s what did the words mean to the people who ratified the Bill of Rights or who ratified the Constitution.

Yet, the analysis that followed took great pains to avoid a thorough exploration of the development of the amendment, the contemporary usage of certain terms or phrases, or the determinations of courts or scholars from times much closer to the amendment’s initial implementation.

In other words, the Court simply assigned an intent to the Founders that satisfied their immediate purpose, but one that did not accurately reflect any reasonable analysis of the available evidence of what might have been the Founders’ actual intent. (See a much fuller explanation of this point, here).

Courts are not solely guilty of this cooption of America’s political past.

One political faction’s mantra embraces the strategy of provoking emotions predicated on just this kind of imagined history. The MAGA movement, as it has been called, presupposes an apparition of the United States as something to ‘return to’ as the foundation of its rhetorical platform. The phrase literally stands for Make America Great Again.

Although the slogan has a thematic appeal, it fails to define when “great” was or what it means. Indeed, the ideology requires ambiguity because no such phantasm ever existed or could be fairly described in a way that would further the movement’s agenda. What is really proffered is an illusory fiction that must be completed in the mind of each adherent.

And this, as we have seen, is quite powerful.

The raw emotional attachment to the abstraction carries far greater weight than the nuanced, complex, and ugly reality. But it says nothing useful to the challenges associated with governing. As long as competing sides persist in battling over dreamscapes that no one can ever truly share, the extant problems in need of solving will simply linger and amplify.

MAGA supporters at a political march. Credit: Times Reporter

The power of portrayal

Virtually every society has utilized conjured histories to achieve political objectives at some point or another. In the present, the ability of propagandists to do so is magnified by the availability of an abundance of emotion-invoking resources. Perhaps the most powerful of these are movies.

Many of these distort historical events far beyond what can be attributed to ‘creative license.’ It doesn’t help matters that they often proclaim to be “based on a true story” or make similar allusions to the accuracy of what they are about to depict. Watch any historian’s breakdown of the problems with flicks like Braveheart, Gladiator, Apocalypto, or the Patriot — all blockbusters — to get some idea.

Unfortunately, these will often serve as people’s first, or only, introduction to the historical events portrayed therein. Even though their producers will claim that they intend to entertain not educate, the result is the same.

Movies are not the only guilty party. Lately, memes serve the same purpose, though, given their simplicity (and frequent ridiculousness) it is hard to imagine how. Nonetheless, scrolling through social media will lead one to thousands of them with associated messages by the posters suggesting their reliance upon them as a source of useful information.

Both movies and memes can alter popular opinion in beneficial ways, as this study of the efficacy of certain memes spread during the pandemic showed, but they remain dangerous for a large number of people inclined to uncritically believe them based on predetermined political proclivities.

In either case, these typesempower the practice of using revisionist history to make political points, points which tend more often to be damaging than useful toward resolving modern day problems.

* * *

I teach Tibetan history and culture at the Dharma Farm School of Translation and Philosophy, including courses on the environmental issues of the Himalayas both in Nepal and on the Tibetan plateau. I am also the executive director of the EALS Global Foundation, which focuses on education in and the application of technology in environmental disaster mitigation.

For more history, law, and politics, head over to my Medium page.