Photo by Riccardo Monteleone on Unsplash

Sex sells. It’s a truism as old as humanity itself. Artificial intelligence, on the other hand, does not. Just last month, MIT reported that 95% of companies investing in AI saw a “stall” in revenue generation or no impact at all.

So, what do you do when a product that likely can never live up to its overhyped promises falters? Give it genitals.

Enter Svedka’s sexualized robots. (Just a note, Svedka is the product. The company that owns it varies depending upon the time being discussed. As such, the product name is used interchangeably).

Svedka isn’t trying to sell AI itself. It is simply using it to push alcohol sales. In fact, its executives have repeatedly asserted they are promoting inter-human contact, something AI and other tech has eroded.

AI companies routinely claim their AI-driven products will ‘do the tasks you don’t want to do, so you can spend more time on what you enjoy.’ Presumably fun with friends. But reality is far different. AI takes jobs, then does them poorly. It inexplicably or unjustifiably revokes people’s insurance. It persuades people to lie and cheat. Whatever time it gives back toward doing things we enjoy, it compensates by worsening our lives.

But the most pernicious thing AI is doing is driving people apart. The subject requires little ink here because almost everyone knows it, yet they continue to fall victim to it. They know social media algorithms create echo chambers, causing them to fight over nonsense. It is, perhaps, the core reason politics in many countries—especially the United States—is so visceral, and stupid. The schism isn’t limited to politics. Whatever the context, people seem to want division even as they protest it.

What a world.

Anyway, those who have discussed some form of ‘takeover’ of AI have asserted that the pivotal point will be its embodiment. In other words, AI will become a true threat to humans when its intelligence is inserted into a physical vessel. Opinions differ on how the threatening part will manifest. Some use analogies to the Terminator, others see it as a more abstract physicality like Hal in A Space Odyssey.

I think it will come about in the vein of Body Snatchers. As described on Wikipedia, the plot is about:

people [who]… are being replaced by perfect physical imitations grown from plantlike pods. The duplicates are indistinguishable from normal people except for their utter lack of emotion.

In the real world, however, the emotionally flat entities will not consist only of the imitations, the AI-bots. Eventually many humans will be indistinguishable from normal people except for their utter lack of emotion. Or, more probable, their lack of humanity. All will be a threat.

In its ad campaign to sell vodka, Svedka is effectively encouraging this outcome by helping mainstream the idea that we can (and, arguably, should) interact with AI-driven bots the same way we interact with humans. All the same ways.

First, let’s examine the campaign. Then, we’ll explore the implications.

Svedka‘s history of sexualized robots

Svedka is a brand of vodka originally produced in Sweden. After the product line was bought out, the parent company moved its operations to the US, perhaps around 2013. Even back when Svedka was still unquestionably Swedish, the company promoted its product in a number of interesting ways.

In 2005, it launched its SVEDKA_Grl advertising campaign. It featured a “shapely” female robot (a.k.a., a fembot) designed by goliaths in the special effects industry, including Stan Winston (who worked on Terminator, Aliens, and Predator, among others). A spokesperson for the company explained that the campaign was presenting a futuristic version of “adult fun” — drinking, dining, dancing, nightlife, shopping; though, specifically not porn.

Eight years later, the company stirred the public again with a version of SVEDKA_Grl that possessed more accentuated female features. Still, some commentators found meaning beyond the synthetic curves. Damon Brown, cofounder of Cuddlr, a social media meeting app, wrote:

The new SVEDKA campaign has us go back so we can remember being optimistic about how robots would change our lives for the better — sexually and otherwise.

Perhaps SVEDKA realizes that the sexualized robot is already a reality, so the best way to appeal to us is with the fantasies of yesterday, not the realities of today.

Brown asserted that the ad campaign sought to “appeal to our idealized view of the future,” but an idealized view held in the 1980s, not the 2010s.

SVEDKA_Grl (2016). Source: payload.cargocollective.com

Zoom ahead to 2025, to SVEDKA_Grl’s resurgence, now accompanied by a male representation (a brobot). Ad executives for Sazerac, the company that currently owns the product, are pitching it in a rather peculiar way:

The Robot’s return is a reminder to look up, reconnect with those around us, and celebrate while we’re here.

Look “up.” Right. (from Svedka ad titled: System Error: Don’t Drink and Hard Drive)

They further proclaim that the ad series is a direct response to a growing tendency of Gen Zs to choose technological communication over in-person contact. In support of this, it seems, the ads show clubs filled with a mix of humans and robots dancing and flirting. The team behind the design explains on their website:

After more than a decade off the air, Svedka’s iconic Fembot has made her return… this time with a new male sidekick and a socially responsible mission: get people off their phones and back to connecting in real life…

From Times Square billboards to digital film spots, the work blends nostalgia with a sharp cultural insight: that the future of nightlife is about real connection, not filtered screens.

Promoting products using subtle (and often not-so-subtle) nods toward sex is not new and not necessarily bad. In almost every case, the message runs counter to reality, but most people know it. For example, beer drinkers in the real world rarely possess the chiseled bodies of nearly every person depicted in beer commercials.

But with AI and humanized robots, it is different. For one thing, humans are already having trouble finding the line between life and machine, and it will likely get much more difficult. This confusion is leading to systemic problems with interpersonal relations and mental health. Moreover, an abundance of evidence shows that using machines to substitute for human contact is problematic, even dangerous.

The Svedka ads are, of course, not responsible for these trends. By putting robots and sex together at the forefront of their message, however, they are striking a powerfully persuasive chord that is helping move humanity along this sordid, and likely tragic, path.

The ads

One can readily dismiss the company’s argument that it isn’t promoting pornography (or at least strongly hinting at it). In its ad titled, “Bigger is Better,” the camera zooms in on the crotch of the lead brobot just after he has a heavily flirtatious exchange with a fembot bartender. He lacks a visible penis, but there is a bulge. The camera cuts back to the fembot that very obviously glances at his package, then raises a lustful eye. Humans behind the fembot also seem captivated by robot-man’s junk.

Notice, in particular, the woman in the center of the image.

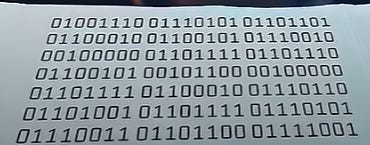

In “Thirst Trap of the Future,” the fembot bartender shakes her (voluminous) breasts in front of a male human. His eyes widen and he smiles, then slips a note to her asking “what is your number?” She looks surprised at first, then cynically amused, and slides back a bunch of binary.

In text it reads, “number one, obviously”

The ad ends with a somewhat fuzzy view of the man, who appears dejected.

A brobot in the center of the dance floor takes a drink offered to him by a fembot in the ad titled, “System Error: Don’t Drink and Hard Drive.” Red liquid courses down where his throat would be if he were anatomically identical to a human, causing his head to spark. He is elated by the ‘electrifying’ experience.

There is something noticeably different in that video, a further hint at what the message actually is. At the 4-second mark, there is a brief glimpse of an odd figure:

It is difficult to zero in on details; the figure is blurred for the full second-and-a-half it is visible. Either it is a woman wearing a robot mask, or a fembot with a much more human-like anatomy and dress.

Examining these three ads closely, the latter seems the more probable explanation.

Throughout, there are robots that look like older or inferior versions. They are more squarely shaped, lacking faces, breasts, or any indication of genitalia. Essentially, they are representations of the ideal of futuristic robots held by people in decades past.

Here is an example. Note the body and facial features, or lack thereof.

Given the message proclaimed by the company in earlier campaigns, it is plausible to assume that just as the square, faceless bots represent past beliefs about what futuristic robots would look like, the hybrid human-bodied fembot represents the expectation of people in 2025.

Because all entities in the videos interact just as humans do, it is not unreasonable to conclude that the implication is that at some point there will be little difference between robots and humans in the (possibly near) future.

Bots for every human desire?

Sazerac spokespeople have made it clear they are targeting Gen Zs with the latest campaign. This group comprises the youngest legal drinkers to people of about 28 years-old. Aiming at that demographic with this kind of content is perhaps the most troubling part.

Although the company has proclaimed to be encouraging “bringing people together,” the ads suggest otherwise. While there is superficial human-to-human contact in the background, the bots are front-and-center.

A human man tries to pick up a fembot bartender in one. When she blows him off, he doesn’t pursue a human, he sits there looking glum. In another, a fembot bartender flirts with a brobot, convincing him to take a drink while she — and some humans — gaze lustfully at his crotch.

The company itself acknowledges that Gen Zs show a tendency to choose interaction with technology over humans. Numerous studies have found that this leads to loneliness and depression. People within the age group themselves are beginning to recognize this. Many have started movements to ditch smartphones or vastly reduce their reliance on them and the habits that take them away from interpersonal contact.

Sazerac’s focus on robots feels like a sort of end-around. It is acknowledging this isolation crisis in its press statements while simultaneously asserting more potentially isolating technology as the solution in its ads. One could view it as the next step following what Character.ai is doing.

Character.ai is an LLM that can be configured into a specific persona. Trend Micro described it as almost “a digital sidekick.” The case involving 14-year-old Sewell Setzer III revealed the deep flaw in using tech to compensate for a lack of social contact this way. The family of the teen filed suit against the company, alleging that the chatbot encouraged their son to end his life (which he did) after he expressed troubled feelings to it.

His is not the only instance of this kind.

The problem will be severely compounded if AI-powered robots become mainstream. Sazerac’s ads offer a vision of a future in which (presumably) autonomous, intelligent robots interact seamlessly with humans, even to the point of pursuing romantic relations that include the physical.

There are too many concerns about intimate human-robot relations to discuss them all here — examples include hacking, greater capacity to steal even more sensitive personal information, or robots going rogue and becoming physically dangerous. But, operational problems notwithstanding, what effect would a future like Sazerac’s vision have on humanity’s mental health?

It is undeniable that companies profiting from these things will cater to any demographic willing to buy. This will include rapists and pedophiles. And it’s already occurring. Duke University researcher Christine Hendren told the BBC in 2020:

Some robots are programmed to protest, to create a rape scenario. Some are designed to look like children. One developer of these in Japan is a self-confessed pedophile, who says that this device is a prophylactic against him ever hurting a real child.

Should a healthy society allow people to engage in their most perverse fantasies, so long as they remain restricted to nonliving entities? Those who argue against allowing unfettered violence in video games would say no. But, even if one thinks committing simulated violence with a controller on a TV screen is fine, it still begs the question of where the line should be drawn.

Studies show that humans evince both positive and negative emotional responses to robots, even those lacking anthropomorphic features, like Roombas. Such responses can include empathy, attachment, fear, or even anger (such as in cases when a person witnesses the abuse of a robot).

In 2016, Kate Darling proposed a way of thinking about formulating regulations on what people should be allowed to do with robots in the context of human emotion and behavior. She wrote:

Framing robots as nonliving tools relinquishes an opportunity: lifelike robots may be able to help shape behavior positively in some contexts. If we were to embrace, for example, an animal metaphor, then we could regulate the harmful use of pet robots or sex robots analogous to existing animal protection laws by restricting unnecessarily violent or cruel behavior. Not only would this combat desensitization and negative externalities from people’s behavior, it would preserve the therapeutic and educational advantages of using certain robots more like companions than tools. [Citations omitted].

Some argue the other way. The creator of the sexbot in Japan (mentioned above) claimed that building robots to enact his abuses prevents him from directing them toward human children. That argument effectively paints the creation of childlike or other rape-victim robots as a moral good. And this may persuade lawmakers or judges.

In 2002, the US Supreme Court struck down part of a law that prohibited “child porn” that did not include an actual child. Depictions of children engaged in sexual activity may have a “redeeming value” (such as an educational video on contraception or STDs), the Court stated, and therefore cannot be broadly banned. The same legal argument could be extended to robots made specifically for abuse.

Would society benefit from giving people very lifelike outlets for committing their most heinous propensities?

Right now, we don’t know. Robots made for mistreatment are not prolific enough yet to generate a large enough study sample. But some researchers have pointed to the ‘paradox’ uncovered in studies about people regularly engaging in video game violence as a comparison:

Some psychological and behavioral studies show that violent games lead to an increase in violent behavior. On the other hand, there are proponents who argue that these video games, even if inclusive of simulations of violence, can contribute to cognitive development, such as improving one’s responses to harm, attacks, or threats. [Citations omitted].

If it is true that playing violent video games leads to an increase in violent behavior, the effect of allowing it in an even realer context (i.e., abusing humanlike robots) would probably be more dramatic and harmful. But as some believe, perhaps there could be some ‘redeeming’ value. The question is whether it is wise to let the market plow forward with this untested and leave us to clean up any mess afterward.

And, of course, none of this contemplates the value of the robots’ perspective.

But, even if society prohibits the maltreatment of robots, there remain other considerations. What effect would easy access to sexually capable robots have on the individual psyche of people not seeking to perform atrocities?

David W. Wahl, a social psychologist, conducted surveys about consensual sex with robots. A key issue raised to respondents was “whether or not having sex with an AI form is an act of infidelity.” The answers crossed the spectrum from a hard ‘no’ to an unequivocal ‘yes.’ Another was what it would do to real human relationships given that a robot can presumably be programmed to ‘do anything.’ Again, there was no consensus.

Some viewed sex with a robot as comparable to using a sex toy, a “fun addition to the sexual canon.” In this line of thinking, individuals or couples can explore their fantasies in a safe way, free from STDs or other associated risks that tend to arise when another human is added to the mix. But this raises questions about emotion when the ‘sex toy’ acts in so many ways like a human (one does not, after all, tend to have fruitful conversations with a dildo).

Put simply, no one knows the impact the widespread availability of either ‘plain-old’ sexbots or robots with advanced intellects that can also engage in sexual activity will have on society. Nevertheless, like every foolish choice driven by the unrelenting quest for capital, it seems we will soon find out the hard way.

Risky futurism

The problem here is the same that has plagued all commercially produced AI over the last decade. Companies simply plunge ahead with the newest development, monetizing and promoting it, without any consideration for the consequences. Even governments have adopted AI into critical functions, and often the result has been catastrophic.

Although the obvious next step in technological progress is to more closely emulate human function through robots powered by advanced software, the trouble is that we have not perfected the previous steps. I’m reminded of a quote from a sitcom that went something like: “Maybe you should master glue before you move on to fire.”

The public is still getting its fingers stuck together while companies that clearly don’t give a damn about anything but money are lighting welding torches. Whether it’s shaking synthetic boobs to sell vodka or promoting lying and cheating with AI, none of this is healthy.