A remarkable cat that few have ever seen, the Snow Leopard (Panthera uncia) lives deep in the mountains from as far south as Bhutan to as far north as the Mongolian-Russian border region. Tibetans living in Qinghai Province, China, refer to the cat as the “Snow Mountain Hermit.” Others have called it the “Ghost of the Mountains.” I am not sure where the latter phrase came from, but it almost certainly derives from how difficult it has been to film and for conservationists to track.

Snow leopards have white to grey colored fur with black spots that morph into rings along their long, thick tails. They are short and stocky in build, usually weighing between 50 and 120 pounds (22 to 55 kg); the biggest can reach 165 pounds (75 kg). Their bodies range from 30 to 59 inches long (76 to 150 cm), though they look much larger as their thick, bushy tails nearly double their overall length. Small ears reduce heat loss, while wide paws maximize grip for their precarious habitat. The tail serves as a giant rudder for both steering and balance—a critical requirement for a stalk-and-sprint hunter whose terrain is vertical rather than horizontal, ranging from 9,800 to 14,780 feet (3,000 to 4,500 meters) in elevation. Snow leopards split from their genetic ancestors around 3.2 million years ago. Today, its closest relative is the tiger.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jhgYK5YwINY

Source: https://www.yarmama.com

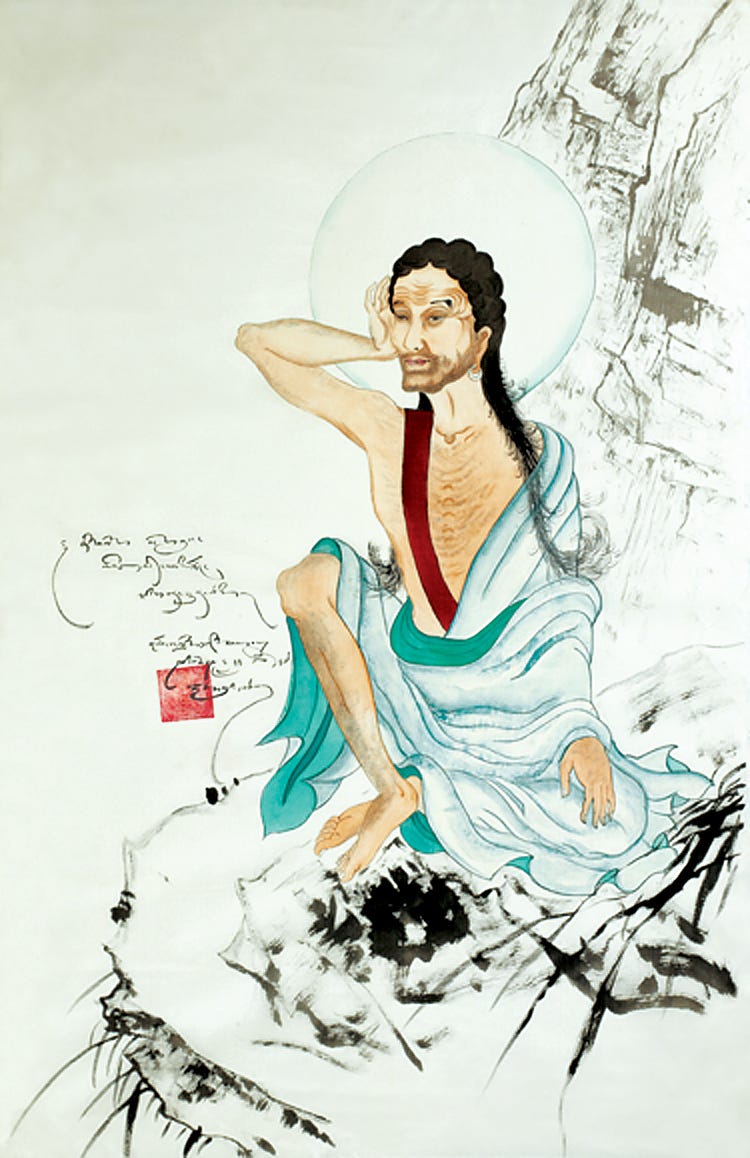

The elusiveness and majesty of the snow leopard has landed it a central place within the mythology of its home range. Milarepa, a famous Tibetan yogi, is said to have spent a rather severe winter meditating in a cave. When nearby villagers came to see him that spring, they instead found—at first—a lounging snow leopard. Later, when finally they located the yogi, he told them that he himself had taken the form of that leopard. The story is part of the larger canon called “The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa,” and details his long, fraught path that eventually led to enlightenment.

Milarepa

A population living in northern Pakistan, China, Tajikistan and Afghanistan, called the Wakhi, believe in a female supernatural entity living in the high mountains there. They view the high mountain pastures as a sacred place, the Mergich realm, the home of these supernatural beings. Snow leopards, called pes, are considered Mergich animals, meaning they are one embodiment of the supernatural spirits patrolling the Mergich realm.

In northern Nepal, some view the snow leopard as the mountain god’s “dog.” They believe snow leopards protect crop fields by preventing grazing livestock from entering them, thus preserving their yields. Others believe that renown lamas from Tibet often visit the region in the form of snow leopards. In Mustang, locals believe that snow leopards are born to remove sins from their past lives, so killing them bestows those sins upon the killer.

Today, the snow leopard population is estimated between 4,000 and 6,500, and is classified as “vulnerable” by the World Wildlife Fund. Major threats to the species include increased conflict with humans encroaching upon its territory, habitat loss and poaching. Another major issue is the impact climate change is having on the Himalayan and other mountain regions. There is an abundance of evidence of how climate change is affecting the Himalayas, see some examples here, here, here, here, and here. Conservation efforts are underway in nearly every country the cat’s habitat touches. The Sanshui project has been operating since 2009 in the Sanjiangyuan area of Qinghai Province, China. Sanshui (山水), which means “mountain water,” covers one of the largest areas where snow leopards live. Working with Peking University, the organization focuses on monitoring populations, performing genetic testing, collaborating with local villages, and performing anti-poaching efforts. Nepal started the Api Nampa Conservation Area in 2010. It covers 734.7 sq. miles (1,903 sq. km). Among many other projects, Api Nampa monitors the habitat of snow leopards in Nepal. Protected under Nepal’s National Park and Wildlife Conservation Act of 2029 (1973), the animal remains threatened by poachers and from conflict with human settlements. Numerous other organizations also participate in the conservation of snow leopards, such as The Snow Leopard Conservancy, The Snow Leopard Trust, The World Wildlife Foundation, The Wildlife Conservation Society, and many others.

Staff of the Api Nampa Conservation Area from https://dnpwc.gov.np/en/image-gallery-detail/16

In addition to the slow rot of climate change and human encroachment, poaching remains a significant issue facing snow leopards. The snow leopard’s beautiful coat, skin, and bones, along with the mythology surrounding its elusiveness, have made it a prime target for poachers. The trade is particularly robust in Central Asia, though it occurs elsewhere. In Kyrgyzstan, for instance, scientists believe the population of snow leopards has decreased by as much as 50 – 80% based mostly on the illicit trade industry. Records of the snow leopard trade in Central Asia go back to 1884, with the first documents on global trade beginning in 1907. Today, trade in skins represents the largest demand, as they are still used in a variety of cultural activities throughout Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and Xinjiang Province, China. Exacerbating the problem are the incredible prices snow leopard skins and coats go for. Investigators have discovered skins ranging in sale prices from $100 (USD) to $15,000. The price often depends on the enforcement concerns in the market or country where it is sold. Coats made from snow leopards also vary widely in price, again depending upon the risk associated with selling them. In Europe and the USA, for example, a snow leopard coat can sell for near $60,000. In China and Nepal, items were found priced at $1,100 and $3,000, respectively, but that was in the late 1980s.

In 1999, the German Society for Nature Conservation signed an agreement with the Ministry of Environment for the Republic of Kyrgyzstan to create a conservation program. One arm of that program is the Gruppa Bars, an anti-poaching team (gruppa bars means snow leopard in Kyrgyz). Their enforcement activities have led to numerous arrests, including 180 over their first ten years. Walter Stoehr created a short documentary titled, “Guardians of the Ghost,” detailing this organization’s efforts.

Chinese authorities have led the way in volume of seizures of illicit poached goods globally. Of course, that directly correlates to China also possessing the world’s largest market for illegal trade in snow leopards, with 103 to 236 poached each year. Moreover, scientists estimate that 60% of the global population of snow leopards live within China’s borders. Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture contains a market where a very large portion of the trade takes place. Located southwest of Lanzhou, in Gansu Province, investigators recorded 60 skins for sale there in 2005. From 2005 to 2012, investigators discovered a further 100 skins selling in the area. Since 2012, the problem there has become transnational, importing skins from neighboring countries for sale in multiple markets including in Shigatse, Lhasa, Xining, and Linxia. Despite the difficulty in capturing and prosecuting poachers, China has made some strides in the process. From 2001 to 2016, for example, China conducted 108 prosecutions, with 87% convicted of poaching charges, not charges related to the illicit sales of the pelts. This has led criminal enforcers to target the poachers specifically, rather than try to nab the perpetrators when selling on the market. With the advent of social media and internet sales capabilities, capturing illicit sales has become ever-more challenging. While China’s market remains strong because of its transnational trade (meaning poachers can kill snow leopards elsewhere and bring them into China to sell), the open sale of items in places like Linxia have declined precipitously, indicating that enforcement measures have been working to at least some extent.

Mongolia has the second largest range by area of snow leopards. Nearly half of the poaching there is believed to be by farmers worried about their livestock. This comports with the fact that Mongolia also has the largest nomadic population in Asia. Once having a thriving trade in snow leopard pelts, the WWF Mongolia announced in 2014 and 2015 that not a single incident of poaching had been detected. Nevertheless, Mongolia’s remote and rugged terrain, and its nomadic population, make tracking poaching incidents especially difficult.

Nepal has been cited as having higher poaching estimates (as a per capita figure) than most of the animal’s other domain countries. The estimated population of snow leopards in Nepal is only around 350 to 500. Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital, however, is known as a hot bed for the illicit sales of snow leopard skins. One of the reasons is its location directly between the Chinese and Indian markets. Part of this is also driven by the price poachers can get for a single skin, between $10 and $50 USD, a substantial cash amount for villagers from remote areas. Another issue contributing to the illegal trade in Nepal is the increasing encroachment of human settlements into snow leopard territories. Herd animals belonging to Nepali villagers provide a juicy—and easier—alternative to wild prey for snow leopards. Despite the prohibition against killing snow leopards (and other vulnerable wildlife) under Nepali law, many villagers do so either out of retaliation for the loss of herd animals, or as a preventative measure against future livestock loss. Snow leopards have been known to kill entire herds of goats in a single attack. Wildlife officials have worked toward protecting the species further by collaring the cats to improve tracking, which will hopefully enhance deterrence of killing them.

Pakistan has a snow leopard population numbering between 200 and 420. Poaching has been a particular problem in Khunjerab National Park and neighboring conservancies, where 13 snow leopards were killed between 2015 and 2022. Illegal killing of wild dogs in Pakistan has also created a growing threat to the leopards as the dogs are a primary food source for the leopards. Also, like in Nepal, farmers and herders in Pakistan treat snow leopards like vermin, and threats to their herds. Shafqat Hussain and his organization, the Baltistan Wildlife Conservation & Development Organization, have been working to increase monitoring and saving the cats. They have instituted a compensation system for herders who have lost livestock to the cats, to avoid retribution killing. The organization also has assisted with building corrals for livestock that prevent incursions by the snow leopard. Despite these efforts and the continued evolution of laws outlawing the killing and trade of snow leopards, enforcement in Pakistan has faltered. One reason is that the penalties are far outweighed by the benefit. For example, as of 2015, the fine for snow leopard poaching was $180 USD, while a single pelt could garner over $1,000.

Russia also has a problem with poaching, despite comprising just over 1% of the snow leopard’s habitat range. As a destination for traders from Mongolia and Kazakhstan, the Russian market brings substantial prices for pelts, up to $5,000 USD. Perhaps as much as 50% of snow leopard kills appear to be non-targeted, conducted via traps set by farmers protecting livestock, likely hampering enforcement efforts as this is a generally accepted practice. As of this writing, enforcement measures do not seem to be a priority in Russia (no doubt lessened further by the war in Ukraine). In 2015, Russian authorities joined with Interpol to investigate organized snow leopard hunts, but I found no indication of whether this netted any arrests.

Poaching is a problem in all of the snow leopards’ domains except for one. In Bhutan, investigators found evidence of only a single incident of poaching locally over a 28-year period, and no local market for snow leopard products. Even foreign poachers are not believed to invade the national boundaries very often. Nonetheless, experts believe retaliation killings do sometimes happen as a result of predation on livestock.

Snow leopards are considered among the most understudied mammals that live on land. Still, they are the apex predator for a vast swath of territory in Asia. Preserving them is critical to the health of the ecosystem of the Himalayas and contiguous ranges. The mythology, beauty and elusiveness of the animal has captivated conservationists and nature enthusiasts worldwide. While significant problems remain that affect the long-term well-being of the species, these conservation efforts provide some hope. Moreover, there are many great stories, videos and documentaries on the great cat. I will leave you with some here:

The Ghost of the Mountains by Sujatha Padmanabhan (book)

The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen (book)

Searching for the Snow Leopard - Guardian of the High Mountains edited by Shavaun Mara Kidd, Björn Persson (book)

The Snow Leopard Project - And Other Adventures in Warzone Conservation by Alex Dehgan (book)

The Ghost of the Mountains by Ben Wallis (trailer)

Snow Leopard – The Silent Hunter, by NHK Japan (documentary)

Silent Roar by National Geographic (documentary)

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, Digital Forensics, and Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I conduct research in all of these, and run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my non-profit’s page here.

To read my series on sustainability, see the first installment here.