Nepal – the World's next Tech Hub?

Maybe not Silicon Valley, but Nepal has the opportunity to carve its own spot

Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

The question has often been pondered: “Who will become the next Silicon Valley?” Of course, the question more directly is asking, what region of the globe will host the next generation of tech developers and innovators? Many inquire about this issue because of the apparent decline of the major corporations currently resident in that slice of California colloquially known as “the Valley.” As professor Margaret O’Mara of the University of Washington put it, the “party couldn’t go on for ever.” What she meant is that companies in Silicon Valley became artificially “supersized” and the current climate suggests the pendulum is swinging the other way. Part of this has been driven by the general global economic downturn that began during the COVID era, and has seemingly accelerated since. This has been reflected in “historic” numbers of layoffs among the big names, such as Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google.

Another factor is the eroding reputation companies from the Valley have earned. Huge scandals such as the Theranos fraud, the imminent collapse of Facebook (ineffectively renamed Meta), the rapid destruction of Twitter, and the recent failure of Silicon Valley Bank (including what looks an awful lot like pre-collapse insider trading by its executives) have smeared the entire community with the stain of greed and filth. And those only overshadow the myriad other scandals, such as the nearly $400 million Google paid for allegedly tracking private internet use, the donor-advised funds (DAFs) issue, or simply the typically lousy work conditions, among others. The apparently precipitous fall of nearly all the big names of Silicon Valley seems like it should have resulted in a virtual explosion of startups. Alas, like the Carnegie days of steel, big business does not concede power easily, and it rarely eschews monopolizing the market. Raghuram G. Rajan, Luigi Zingales, and Sai Krishna Kamepalli explained how when big companies acquire startups, they tend to create “kill zones.” These researchers noted that because big tech companies trade in user data, there is little incentive for new application developers to attempt to build their product. Selling out to the big companies is far more lucrative, and easier. The big tech companies maintain their hold on the industry, and innovation is limited to the agendas or business models of them only. As a result, the previous two decades have seen a significant decline in overall innovation.

Nonetheless, hope hovers on the horizon. United States regulators have shown an increased interest in enforcing antitrust provisions. Continuing this trend will benefit the entire globe as many of the biggest tech companies reside in the USA. European Union regulators have taken an even more steadfast approach on big tech monopolies. And the same can be said of many other governments. In some places, local tech companies are taking advantage of their localized knowledge to create parallel apps that are more attuned to conditions within their communities, thereby edging out the big companies. An example of this is two startup map applications seeking to provide improved accuracy of Nepal’s many twisting roadways and sometimes chaotically disbursed landmarks. As both a resident of and visitor to Kathmandu, the nation’s capital city, I can attest to the wild inaccuracy of big tech map apps of the city’s many winding, and swiftly changing streets.

Thus, there remains a glimmer of hope that Silicon Valley’s influence will wane. Some success has developed already in India. In 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi told the Raise 2020 conference, “We want India to become a global hub for AI.” The city of Bengaluru (formerly Bangalore) has been called the “Silicon Valley of India” for at least the last 3 to 4 years. In 2021, London & Partners, the Mayor of London's international trade and investment agency, declared Bengaluru as the world’s “fastest-growing mature tech ecosystem in the world since 2016.” It cited a rise of investment from $1.3 billion USD in 2016 to $7.2 billion in 2020, ranking it 6th in the world for venture capitalist investment. Bengaluru wasn’t always such. The city was helped by support from the central government to promote small and medium businesses. Moreover, the city hosts a number of educational institutions, which has created a ready-made workforce that can immediately fill spaces in newly emerging enterprises. A piece of luck further strengthened the city’s growth—Texas Instruments established facilities there in 1984, which opened the door to greater interest from other technology companies.

A key factor in Bengaluru’s history was continued government support. Not only did government programs facilitate the expansion of necessary infrastructure, but it also streamlined the registration of new companies, reducing the red-tape and, more critically, startup costs and time. In a time-sensitive industry like tech, the importance of efficiency cannot be overstated. Just about 2 weeks ago, the Karnataka government approved 18 projects, with investments nearing $1 million USD. Not only has the efficiency of starting new companies held priority, but the government has also actively sought to keep Bengaluru on the map as a destination for tech startups. On November 2, 2022, for example, the Karnataka government held a three-day “Global Investors’ Meet,” from which it expected to help bring Rs 5 lakh crore, or about Rs 5 billion worth of investment. To illustrate the importance of the event, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, Industries Minister Piyush Goyal, and Coal and Mines Minister Pralhad Joshi, along with Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai and state cabinet ministers attended the event. Engaging in such efforts helps to appease concerns of potential investors, but also provides an important marketing tool to attract new investment.

The focus on education in Bengaluru has been another key factor in its growth. Bengaluru’s engineering colleges-to-population ratio is 5x higher than that of Delhi and 1.7x that of Mumbai. In addition, 44% of migrants to the city come with some level of technology background. Bengaluru’s population is also comparatively younger than other major Indian cities. This youthful population is due in part to the employability in Bengaluru, but also to the increased number of businesses that appeal to that generation. Government support for education early on, and continued attention paid to supporting institutions evolving with the global market, provided the critical foundation for the education sector to reach these milestones. Such support helps keep tuition down and enables colleges to acquire the resources needed for success. This goes hand-in-hand with support for the infrastructure necessary to foster this environment, such as ensuring ample public transportation and affordable housing.

Despite all of this, Bengaluru may have already bypassed its peak. Its high period occurred between 1999 and 2004, according to some sources, with subsequent government administrations showing lethargy in maintaining the necessary infrastructural elements to keep Bengaluru at its pinnacle. A chief complaint, for example, is the degrading condition of local roads and telecommunication wiring. Some government officials have noted that industrial expansion has exceeded the physical space and legal capacity for the government to address. In addition, external competition in other countries, even in other Indian states, has eroded the monopoly of interest Bengaluru once enjoyed. Moreover, Bengaluru may not be insulated from the decline we are seeing in Silicon Valley. Before the pandemic, for instance, holding onto employees challenged many companies because demand enabled workers to move to new, higher salaried positions with regular ease. Since COVID, however, some companies have commenced layoffs and salary offers are diminishing. Although some attribute this to a ‘level-off’ from the city’s explosive rise, others fear it harkens an end to the “glory days of last year.” India’s nationwide downturn in IT hirings no doubt has had an influence as well. Add to that a shift away from remote work, which effectively reduces the available employee pool. What’s worse, experts expect plummeting hiring to continue through 2023. Furthermore, like any place where money freely flows as a result of a lively economic environment, Bengaluru has also faced increasing corruption issues. In August of 2022, for instance, more than 1,000 cases remained docketed under the Prevention of Corruption Act. Bureaucratic apathy, willful disregard, or just simple red-tape entanglement had to that point, at least, prevented the cases from being transferred to the local jurisdiction, and thus those cases remained unadjudicated. During the six years (2016 – 2022) when such cases fell under the authority of the now-defunct Anti-Corruption Bureau, a total of 2,121 cases had been registered. In a population of the size living in Bengaluru (18,065,540), that case load does not seem extreme, however the failure to prosecute such a large percentage of corruption cases is a major problem. Such apathy can seriously erode investor confidence.

For Nepal, this is not bad news.

Nepal’s current economic climate is, in my opinion, one of many ingredients readily available for cooking the country into the next big tech hub. The unemployment rate in Nepal (defined specifically as including only those who are actively seeking jobs) in 2022 was listed as 5.1%. This figure does not include the hundreds of thousands of Nepali laborers forced to take employment abroad each year. In 2021-2022, for example, the Department of Foreign Employment issued over 630,000 labor approvals for work abroad, a near-record number. Combining this figure with the unemployment numbers mean that there is a significant workforce available to steer toward the development of a technology hub. The Central Bureau of Statistics determined the average salary of workers in Nepal as NPS 26,700 in big companies, 25,800 in medium companies, and 16,768 in small companies per month. It developed these numbers in 2020, so it is possible that they are even lower following the upheaval caused by COVID. By comparison, the average salary in Bengaluru was around 117,000 NPS, with tech jobs often much higher. This means that tech startups opening in Nepal can pay somewhat lesser salaries than those in India, making Nepali companies more competitive globally, while still improving the standard of living for Nepali workers.

Technological infrastructure in Nepal has improved dramatically over the last decade. The chart below shows the extraordinary rise of internet use. According to data from Ncell and Nepal Telecom (NTC) released in 2018, smart phone penetration had reached 50% of the population. In 2020, that number exceeded an estimated 70% of the population. In June 2022, NTC began testing 5G across various parts of the country. This follows a near 98% coverage rate of NTC customers receiving 4G network access. In addition to that, NTC has coverage in all 77 districts of Nepal, with some remote districts already receiving at least 4G service (though this remains limited to specific areas). E-commerce and telecommunications are also growing with vigor in Nepal. The US Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration has identified this industry as a “best prospect” investment sector for foreign investors.

Despite some issues outlined by market evaluators, Nepal has recently achieved two significant feats that can only help with developing the country as a tech hub. As a landlocked country, Nepal’s export industry has relied heavily on air-traffic, itself limited to just one international airport—Tribhuvan. Today, however, new airports in Bhairahawa and Pokhara exist and need only to find support for the development and regulation needed to enable them to become international air-export hubs. This would enable easy, and potentially cheaper, export of tech hardware and other items the tech industry could produce in Nepal. Moreover, the existence of those airports in those two places, where development is cheaper and easier (perhaps) than in Kathmandu, provides yet another golden opportunity for Nepal. Development of Nepal as a tech hub need not be limited to the crowded streets of Kathmandu only. With the recent opening of the Rasuwagadhi-Kerung crossing on the Nepal-China border, and still others to open soon, there are now numerous physical access points to external markets.

Education in Nepal has continuously grown both in volume and quality over the last two decades. Unfortunately, this increase has not manifested in higher education—schooling beyond the +2 level. One report lists the numbers as 4.6% having completed a Bachelor’s degree, while just 2.2% have completed a Master’s degree. Moreover, Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) notes the significant number of Nepali students heading abroad to attain their higher education and subsequent career opportunities. This “brain drain” in Nepal presents serious problems for development. The prevailing causes seem to be the quality of education, the lack of career counselling and guidance, and the teaching of skills and credentials needed to compete in the global job market (and of course fears over economic and political stability in the long term). Many schools are seeking to address some of these concerns. For example, one group is in the process of starting a new university which will embrace the programs needed for global competition in the market, including teaching skilled programs companies want and need. At least one college is implementing new programs targeting very specific areas of computer science, IT, and forensics for new degree programs and certification of particular skillsets. And others are seeking ways to admit students of lesser means into tech-oriented programs. Still others are offering technology programs built around producing ready-to-work students. (Full disclosure: I am advising on some of these projects and thus am not identifying any of them by name). The government could also boost these efforts. The creation of technology scholarships and other funding efforts would enable many more students to enroll in these types of programs.

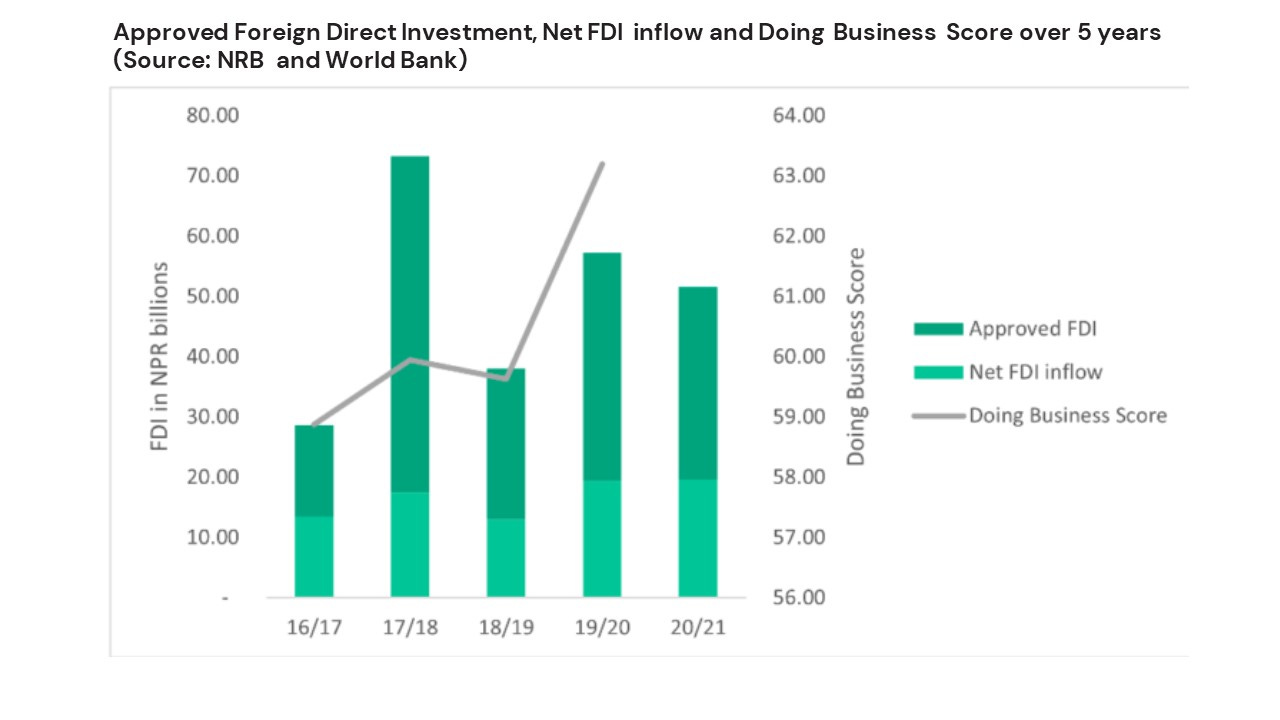

Another way government could increase the ability for entrepreneurs to turn Nepal into a tech hub would be through the easing of restrictions for allowing foreign investment and participation in technology startups in Nepal. The Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer Act, 2019 (FITTA) has shown what appears to be increased accommodation by the government to facilitate technological growth. That Act sets the minimum threshold for foreign investment in Nepal at NPR 50 million, but a 2021 amendment allows only 70% investment upfront. That amendment raised Nepal’s “ease of doing business” rating by the World Bank. Indeed, Nepal’s Information Technology sector has experienced the highest Compounded Average Growth Rate (CAGR) of any industry in the country over the last 5 years, a growth rate of 141.23%. Still, improvement in some areas could significantly bolster these numbers. Examples include quickening the process of foreign direct investment approval. As noted above, the technology industry operates at high speed. Bureaucratic barriers that slow the development process might cause lucrative investment opportunities to shift elsewhere. The repatriation process for profits for foreign investors also should flow more efficiently. While it is understandable that the Nepali government wants to keep careful control of outflows, finding a way to do that without frightening away investors by a sluggish repatriation timeline would put foreign investors at greater ease. Smoothing the way for new technology startups would increase the employment opportunities for newly-minted Nepali graduates to find jobs right away.

Nepal is situated in a moment where different decisions could lead to profoundly different futures. Many factors have come together leading to an opportunity for Nepal to take its place as an emerging technology hub. To be sure, much work needs to be done. But the available reforms require more willpower than resources. Indeed, merely opening the door wider to external investment itself could be the push needed to ignite the market enough such that increasing volumes of resources will become available to launch other programs, such as scholarships or infrastructural improvements. There is no absence of potential in Nepal among those already trained in technology fields, or those aspiring to join them. Nepal’s economic condition is simply in need of a springboard to put great numbers of its citizens to work, at home where they can work on strengthening their own country. Technology is the future’s market. Everything else will be secondary. The opportunity is there for the taking.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run the EALS Global Foundation non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

For a discussion about the growth of technology and technology education, check out this podcast episode discussing the topic with Softwarica College of IT & E-Commerce’s Campus Chief, Mr. Pramod Poudel.

Innovation in Nepal

Welcome to the Evidence Files Podcast! Each episode will feature a new guest with all sorts of interesting backgrounds talking about a variety of subjects. Subscribe to receive email updates about the release of new episodes as well as the latest articles on technology, Nepal and its culture, science, environment, aviation, and also some random topics. …