Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

I left Kathmandu on October 21, at the beginning of the Dashain celebration in Nepal. Traveling with a small group of people very close to me, we piled into our sedan, bags in tow, and headed east toward Dhulikhel. During this festival time, millions of people leave Kathmandu to head homeward, whether to villages in the hills or mountains, or to the flatlands of the Tarai. By the time we had reached just Bhaktapur, vehicles already clogged the highway, all headed in one direction—out of the valley. We slowly plodded along the clean, wide highway until such time as it gave way to a two-lane, dustier thoroughfare. From there, we were at the mercy of the traffic all the way to our turn off in Dhulikhel. We left the main road in that town, heading northward into the hills. Alas, we were not alone. Hundreds of vehicles, from tiny scooters to massive buses, lined the roadway for some distance into the hills. Adding to the chaos, the road appeared to be in the early stages of construction, littered with holes and protruding stone. Indeed, many vehicles blocked portions of the passage, beset with flat tires or other problems. In all, the traffic slowed our progress by nearly an hour, but finally gave way as we departed yet another main roadway and headed deeper into the hills. At long last, our path fully opened up allowing us unfettered travel whilst simultaneously providing incredible views of the rolling, terraced hills.

Many fantastic roadside places dot the drive to Dolakha where one can stop for coffee or a snack. In between, small villages occupy the countryside wherein merchants offer any number of commodities for the weary traveler. We did not avail ourselves of any of these until lunchtime, at which point we found a remarkable resort snuggled along the Sunkoshi River. At a place called Sukute Beach, we enjoyed a decent meal—served buffet-style—along the banks, themselves graced with sandy beaches and lush forest.

Sukute Beach Resort – all photos taken by author

Our bellies full, we hit the road once again. As we climbed higher and higher, the air grew ever cooler and the sky flitted between partially to fully clouded. At a modest height of around 2,000 m (6,500 feet), we arrived at what an American might call a ‘rest stop’. I am not sure of the name of the place, but it was only a short distance before Mudhe. This small strip of stores and restaurants offered a wonderfully hot tea made from black pepper and ginger accompanied by a pretty view of the hills. In the considerably colder temperatures (compared to Kathmandu), the heat of the tea and spice rejuvenated us for the hundred or so kilometers remaining.

After a short time, our first destination lie on the horizon—the tiny city of Charikot (now known as Bhimeshwar). You could see it from the road long before we would arrive there, perched as it is on an adjacent hill. Once in Charikot, we needed to trade our Volkswagen sedan for something a bit sturdier—a Mahindra four-wheel-drive jeep. After all, the next place we headed required an uphill climb, most of it on what one could only call a path (as opposed to a road). Our goal was to reach Kalinchowk, a hilltop town residing at around 3,000 meters (9,840 feet). Between the traffic and our roadside stops, as well as waiting for the 4x4 itself to arrive, we did not commence the climb until the late afternoon, perhaps around 4pm. In the hills, dusk comes early as the sun dips below the surrounding landscape quickly spreading darkness over the lower lying areas. It seemed probable our journey up the hill would conclude well after dark.

The initial journey up took us through a few small villages on a relatively decent road. Indeed, once we climbed aboard the hill itself, the first few kilometers of road consisted of beautifully paved concrete. After a short while one of my astute, young fellow travelers noted that the “marketing” road was about to end and the “real” road would now begin. And indeed it did beginning with a short thump off the finished concrete down onto a mud-packed pathway, pockmarked with numerous holes and rutted from previous traffic. Our vehicle rocked back and forth as the driver slowly and steadily navigated the rickety terrain, continuously ascending. Through lush forest we moved, awed by the resplendent view of the surrounding hills.

Yes, that is the road.

On this section of road, we passed virtually no remnants of civilization, absent an isolated farmhouse or two. Upon rounding one corner, however, we encountered a small village that thrived almost exclusively on farming the great beast of burden of the mountains—the yak.

From there, darkness descended on the heels of a thick fog. Dense as yak milk, the ground-cloud obscured nearly every landmark, forcing the driver to lean toward the windshield to follow what contours of the road he could see. Progress understandably withered to a crawl at that point, and with the chill moisture pervading the air the temperature precipitously plummeted. Our jeep inched along the worsening road while we shivered inside. Finally, we crested the giant hill and the fog diminished some. From our great height we could see light ahead. After a few more curves, we would reach our destination.

A small valley between the two peaks of the great hill holds the village of Kalinchowk. The town seems to serve exclusively as a tourist destination, but one somewhat left behind the modern era. Reminiscent of the village of Bree from the Lord of the Rings movies, Kalinchowk hosts a number of hotels and lodges, and little else. In the cold darkness, we saw few people around. Some of the places looked shuttered for good, while several glistened with colorful lights. Still, aside from a forlorn mountain dog wandering the wet road, the place did not exactly teem with life. Nonetheless, we pulled up to our chosen lodging, the Hotel Diki, where the owner met us with a warm greeting while another gentlemen offloaded our bags.

Hotel Diki, Kalinchowk, Nepal

Kalinchowk Village

Did I mention it was cold? Without the luxury of a thermometer, at a minimum I knew the temperature sat below freezing, evidenced by the ice on the pavement and the occasional icicle hanging from an eave here and there. From just 10 or so hours before, we now experienced a temperature difference of about 45 degrees (Fahrenheit) (7.22 Celsius). Add to that the frigid, sloppy rain dripping upon us and one can imagine the efficacy with which it permeated our bones. In any case, the lobby of the place resembled an old saloon, replete with a fully stocked bar. Despite lacking any substantive warmth, the place offered a visual version of it.

Me and one of my stalwart travel companions.

Hotel Diki Lounge Room

We sat down to a solid meal of Dal Bhat with chicken before retreating to our quarters for the evening. After all, we intended to rise before the crack of dawn for the most spectacular part of our visit—the whole purpose of coming to Kalinchowk, in fact. Before that, though, we discovered a few interesting tidbits about our accommodations. First, and most noticeably, the lodge had no heat. Still acclimated to the near tropical heat of Kathmandu, this night would test our resolve. In addition to that, the infrastructure of the place hardly could be called up-to-date. The electricity worked, though only on one side of the room, and a pipe in the bathroom produced a steady drip of water that kerplunked to the floor with the rhythm of a ticking clock. Each drop of water partially froze as it settled leaving a slightly slushy veneer over every surface. It didn’t help that the bathroom window did not possess a fully fitted glass pane, so the brisk mountain breeze blew in unimpeded, only furthering the frosting of the tiny room.

The overnight proved even more numbing, though thankfully the staff did provide an abundance of blankets. I slept wonderfully despite the cold, likely helped by the purity of the air. Nonetheless, the morning demanded a certain stoicism because the wintry air provoked every internal instinct to remain within the warm oasis beneath the covers. Once upright, however, the only viable option was to move around to stave off the chill. It did not require much motivation either, for I knew what lay in store outside. Glancing out the window at the end of the hallway, I saw glimmers of the rising sun already bathing the village in a golden glow.

Some of our group struggled to wake on time, so once everyone was up, we forewent breakfast and immediately headed to our goal. A biting wind blew through the village, creeping between even the thickest of layers (and frankly, we didn’t prepare our layers for this level of cold). We hustled along a cobblestone road toward the outskirts of the village. Alongside the road, several local people sipped hot tea to fight off the winter-driven morning malaise. They gazed at us with interest, perhaps unused to seeing Western tourists or simply amused by our comical outfits given that none of us wore actual winter gear. Instead, we bundled with sweatshirts and shawls, and anything else with which we could keep warm.

After a short walk, we arrived at our destination. It did not disappoint. Hiking up a small hill at the end of the village, we were met with a sight that even the word exquisite fails to capture. There, sprawling across the horizon stood the mighty Himalayas.

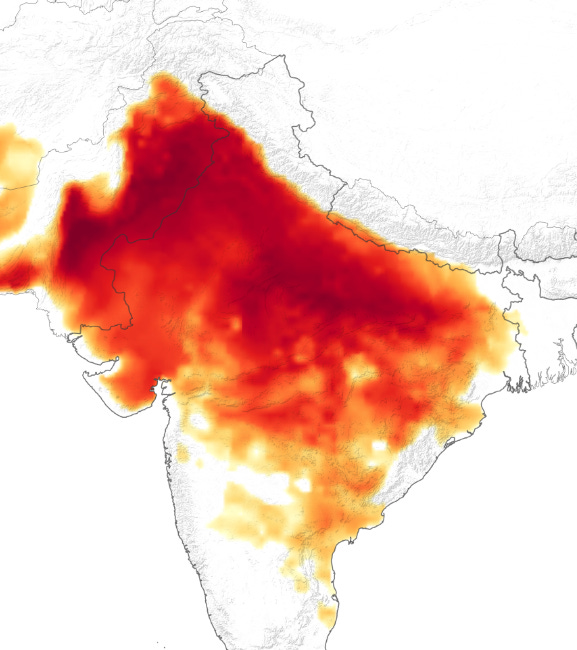

For a person from sea level, no matter how many times I lay eyes upon the roof of the world I cannot help but feel the inconsequential nature of our existence juxtaposed against those massive, ancient megaliths. Though the highest of them resided some distance away, the mountains nevertheless loomed over everything, reminding the world beneath who truly reigns. Snow-capped peaks glistened in the horizon, while the slopes beneath bathed in an out-of-this world sheen of blue. I could not escape a brief sense of foreboding, knowing as I do the trouble we face as the snow pack on those peaks rapidly melts away from the irresponsible disregard humans have for their environment. Soon we would ascend the last slope, the highest point of Kalinchowk, to look upon the mountainous majesty from a view unhindered by surrounding structures.

At the crest of the hill sits a small tourist destination and holy site. Several locals live at or near the top, selling necessary wares such as water to combat the dehydration of elevation, or religious items for those wishing to spiritually immerse themselves. The crest of the hill barely offers any flat space; instead, it feels more like straddling a rather rounded tip. The walking paths are not for the faint of heart… or at least those fearful of heights. Though railings line the most dangerous parts, the drop off is noticeable and can easily induce vertigo. Overcoming the negative side effects of the great height and perilous trail, though, leads one to a site beyond magnificent. Although pictures never do justice to the real thing, I will allow them to speak for themselves here insofar as photos can.

The last photo shows the village with our lodge down below (to the right).

After a morning of pure ecstasy gazing upon the extraordinary beauty this planet has to offer, we headed back to the village to collect our belongings, hop into the truck, and adjourn to our next stop—Shailung Rural Municipality in Dolakha.

Shailung

From Kalinchowk, we descended the hill, passed through Charikot, and drove along the Swiss-built roadway to Shailung. For a few dozen kilometers, the perfectly paved road wound its way through the hills, trickling downwards even further until it ran alongside the Tamakoshi River. Not long after reaching a parallel track to the water, we came across a small marketplace. Here, farmers hosted bombastic stands made merrier by an enormous variety of colorful fruits and vegetables. Retailers offered no end of goods from clothing to car parts, and a couple restaurants blared Nepali music. The paved portion of the road continued over a single lane bridge, but our route took us in a different direction.

Looking back at the marketplace from the bridge over the Tamakoshi River.

From here we needed to embark upon another rugged road, one that would once again rise above the shores of the river and back to heights well over 1,000 meters. Our driver took a few moments to check over the vehicle, ensuring it would survive the challenging terrain without issue. Looking ahead, we could easily see the remainder of this drive would bring us into the hinterlands of Nepal, an area where survival from the land was the norm and needs beyond that require long trips on foot for most people. With a growl, our 4x4 lurched forward, eager to defeat whatever obstacles it might meet.

The beginning of the road to Shailung rural municipality.

It did not take as long as I expected to reach the place where we would stay. For the next few days, we would live as the locals at my friend’s childhood home and farm in Dhunge village, Shailung. Our arrival occurred in perfect concert with the flavor of our stay—the driver determined that the last stretch of road was too muddy for a full load of people, so he advised we collect our things and hike the last bit. Encounter, adapt, move on! Fortunately, we did not need to haul our luggage too far—perhaps two or three hundred meters with only a short stretch uphill.

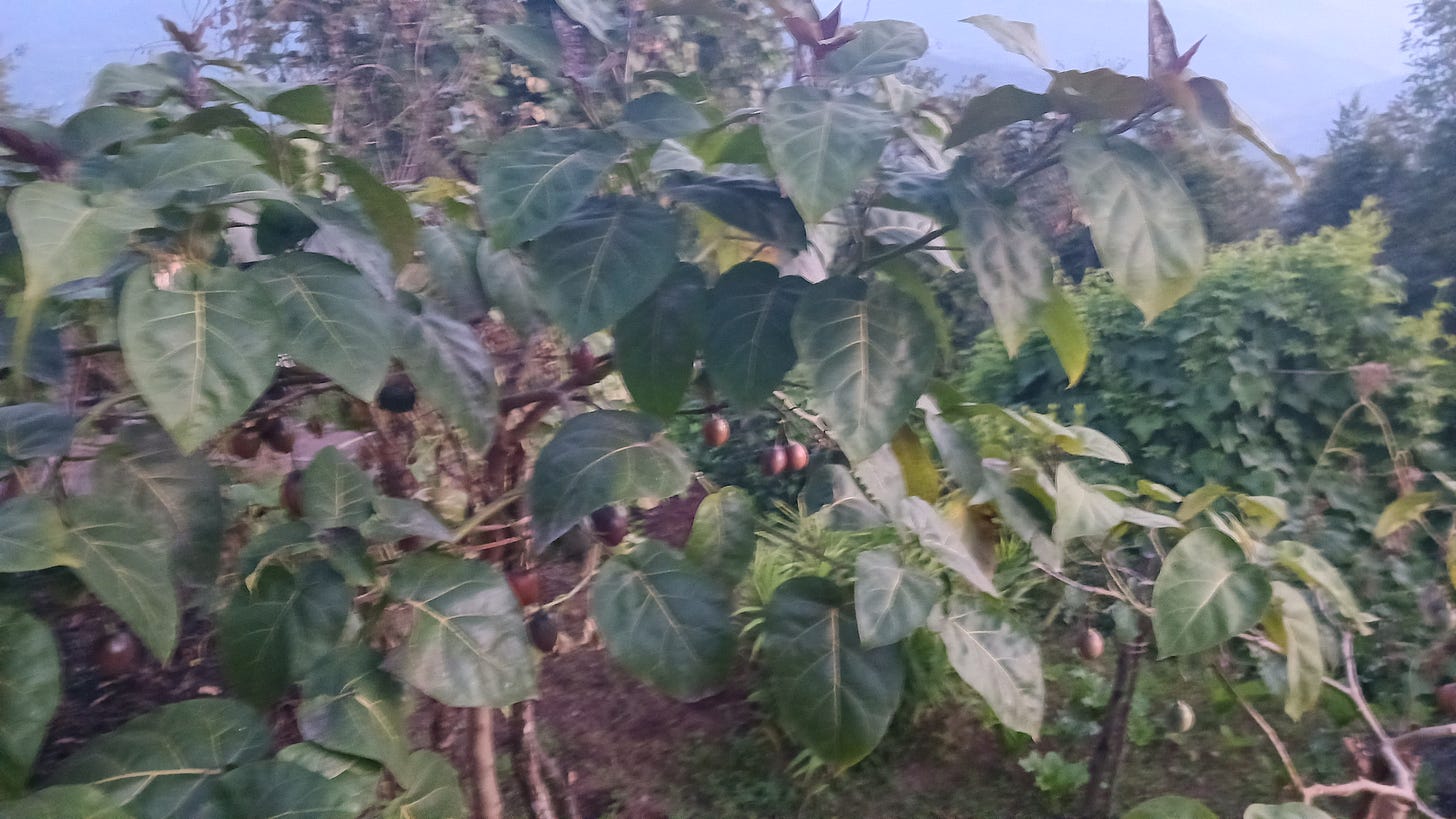

We pushed through some shrubbery onto a small dirt path. Slithering up a somewhat slippery trail, we navigated a gentle curve to see an astonishing sight before us. There, nestled within the surrounding jungle, stood a farmhouse and crop field that seemed right from a book. The house (actually three separate structures) was made of painted stone adorned with balconies and pitched roofs. The front faced outward toward the distant hills, behind which loomed a significant part of the Everest section of the Himalayan range. Between the house and that stunning view grew every kind of plant imaginable, from kiwis, tomatoes, and cucumbers, to a variety of herbs, spices, and so many other things. I learned later, which I discuss a bit below, that Dolakha is one of the voluminous producers of many foods that Kathmandu has come to rely upon. For now, all I knew was that the sheer volume and variety produced here would be the source of awe for many a farm in America.

Our lodgings in Dhunge village.

A view of the crop fields.

As we walked toward the house, we heard the bleating of goats and the crowing of a rooster. Those normal farm sounds caused no particular alarm. It wasn’t until we neared the enormous buffalo that us city folks took some pause. As an avid watcher of National Geographic, David Attenborough, and many others, I suppose you take for granted the enormity of creatures you only routinely see on the television. Up close and personal, however, the sheer size and power of even grazing beasts becomes striking. Thus, when a 1,000+ kg (2,200+ pounds) sow turned and huffed in our direction, many of us jumped in surprise and a bit of anxiousness. This picture does not do justice to the point here.

This picture is low-res, taken as it was from a very respectable distance!

We spent a fine evening around a warm fire, filling ourselves on mutton Dal Bhat. My friend who had grown up here regaled us with tales from his youth, describing what life was like before electricity, and explaining the various sounds we heard in the enveloping darkness. Of course, these days local homes did have electricity even if the rooms themselves maintained their rustic persona. Regardless, we enjoyed plenty of comfort and heat; thankfully the Shailung hills did not get as cold as Kalinchowk.

Our comfortable room.

The next morning, sunrise bathed the farm in a spectacular aura. Creeping ever so slowly over the hilltops, when it finally topped the distant hills the golden orb shown with terrific ferocity and grandeur.

Beneath this divine light we enjoyed a wholesome breakfast. Upon completing our various morning rituals (in my case, imbibing a steaming cup of coffee), we prepared to initiate a new day. Once again, we piled into a 4x4 this time heading to even higher heights—a place called Kalapani. The road up surpassed the difficulty of any previous one, riddled with yawning ruts and large rocks, sometimes tiptoeing beside a substantial drop-off. Nevertheless, travails aside, the journey offered splendid views of the Nepali countryside. We witnessed terraced hills dotted with corn fields and rice patties, colorful lonely farm houses, and vibrant forests. Freshwater springs regularly flowed from the cliffs above us, oftentimes washing right across the roadway forcing our driver to carefully navigate them. When adjacent to the dark pine forests, you could feel cool, fresh air cascading out from within.

Finding our way to Kalapani proved difficult at times, with our driver frequently inquiring with locals to learn the way. After nearly two hours, we managed to reach there. Upon parking and exiting the vehicle, we were met with a stone stairwell that seemed to stretch on forever into the distance. Plodding along one step at a time, sucking air of limited oxygen, we left the steps and embarked upon a very old stone trail through deeply shaded woods. After a seeming infinity, we emerged into bright sunlight dotting numerous hilltops. This place is where Shailung earned its name, meaning in Nepali “100 hills.”

Following a brief break for some revitalizing snacks we continued upwards, now surrounded by these mini peaks all laden in a brownish green, their usual color in the season following the monsoon. Walking for another half an hour, we at last found ourselves on the uppermost hilltops overlooking the entire area with an uninhibited 360-degree view. Having reached there late in the day, the mountains unfortunately lie behind clouds in many places. Nevertheless, the view was breathtaking.

After several days, we eventually returned to Kathmandu. My stay in Dolakha embedded within me an even more profound respect for the lifestyle, resilience, and ingenuity of the villagers of Nepal. I left feeling revitalized, both from the fresh air and a newly imbued optimism that the world can take a turn toward a more sustainable future if it can muster the political will reinforced by the available examples of how to proceed, illustrated by the way these people coexist with their environment.

Dolakha – a Critical Organ of the Body of Nepal

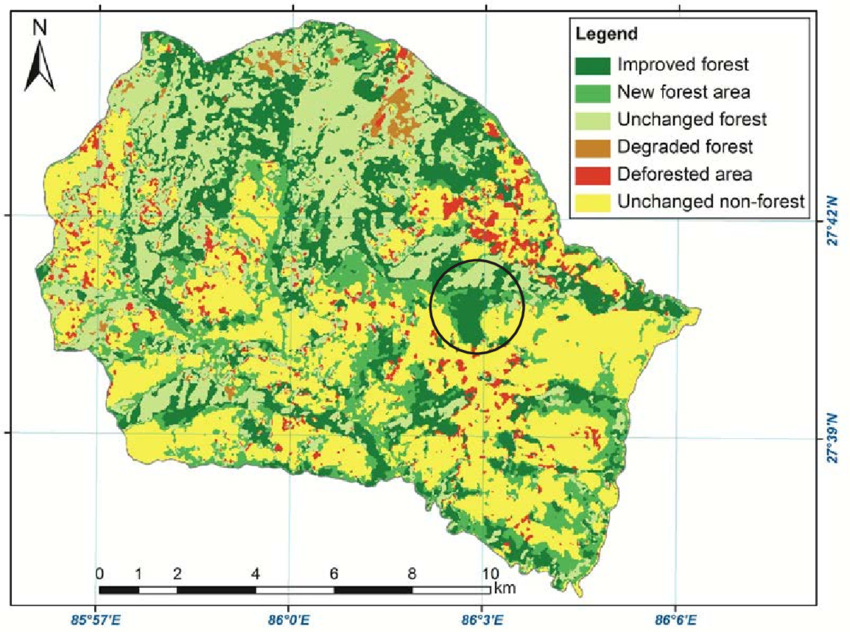

The importance of the Dolakha district to Nepal cannot be overstated. An indelibly verdant landscape, Dolakha enjoys the desperately needed benefits of the forest and a vast diversity of nutritional crops. Beginning in 1990, a program commenced named the Community Forestry Program. The goal was to encourage local communities to work toward replenishing the forests of a large section of the region. An analysis in 2010 showed that the program was a resounding success, having increased density each year by as much as 3.39%. This increase resulted from regular tree plantation and improved forest management.

Credit: Surya Kumar Maharjan

Reforestation carries many critical benefits. Added trees help offset carbon emissions into the atmosphere improving air quality, perform natural filtration of water, sustain wildlife, and provide relief from increasing temperatures for those who have limited ability to escape them. Studies from the Community Forestry Program indicate that the initiative improved the lives in one way or another of over 2,177,858 households.

Farming in Dolakha has seen a resurgence in recent years, though local farmers still struggle to make a sufficient living. The area contains tremendous capacity to grow valuable crops, such as cardamom, tea, garlic, cauliflower, peas, tomatoes, chili peppers, kiwi, oranges, pears, and ginger, among traditional crops like corn, potatoes, cucumber, barley, rice, buckwheat, and various types of millet. The farm at which I stayed grows a substantial variety of crops, including most of those I just listed.

Frankly, I remain thoroughly impressed by the diversity of crops farmed at this single house by essentially just two or three people. And that does not include caring for livestock like the massive buffalo I mentioned above, and mischievous goats and chickens. And this is the norm among farmhouses in this region.

Conclusion

The rural lands of Nepal contain an incomparable beauty and resilience, yet face a simultaneous looming threat. As the climate changes, people who live off the land in this heavenly place face little choice but to adapt—and rapidly. My trip served two purposes. The first, to enjoy this miraculous landscape as a tourist and guest. As such, I made every effort to generate as little waste as possible while trying to learn about how the residents here survive and thrive. It is not the methods that the people—who have been here for centuries—use to survive that imperils the ecosystem. Rather, it is the outsiders who repeatedly intrude, driven by a desire to exploit the opulent region for its cornucopia of valuable items, be them water, sand, minerals, vegetation, land, or wildlife. Innovation by the local people, then, requires contemplating these very human factors in addition to those imposed by the global imposition that is disproportionately affecting Nepal. They sit in a rather unenviable position.

My second purpose, however, involves bringing the local people some tools for dealing with these foreign influences. By foreign I do not simply mean burdens levied by outsiders who possess motivations different than those of the residents, though these are included. I also mean the factors affecting the local people’s lives that are foreign in that they are generated from places with which these folks have no familiarity and little to no knowledge. The devastating effects of mass urbanization, the burning of fossil fuels, the over-reliance on personal vehicles, and the production of harmful materials like plastics and carbon emissions are not things that local people encounter or contribute to and thus do not think about often, if at all. The tools about which I speak did not accompany me on this trip, but instead they are part of a larger effort upon which my friend and I are just beginning. More will come related to that later.

In the meantime, I wish to encourage anyone who is able to pay a visit to the remarkable rural areas of Nepal, to whatever district suits you. Seeing the pristine forests and stunning mountains really brings home the urgency with which humankind needs to address the ongoing climate crisis. It is much harder to swallow the pills hawked by those who benefit from spreading the lies of denialism once one sees these places in person. I cannot state loudly enough how much of an impact this experience had on me and will almost certainly have on anyone else. To those who accompanied me on this trip, thank you for organizing it and making it more profound. Despite my brief diversion into darker considerations provoked by this trip, I remain filled with wonderment and optimism driven by the innumerable generous people I met along the way.

Happy Dashain!

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

For more on how climate change is affecting Nepal, click on either article below.

Wow ! Your writing and photos made this just an awesome read. The top of the world.