Photo by author using craiyon.com

There is one excuse for every mistake a man can make, but only one. When a fellow makes the same mistake twice he's got to throw up both hands and own up to carelessness or cussedness.

— John Graham; Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son. (~1890)

A little over five years ago, Microsoft sent its customers a profound message: use our new product or face potential consequences. It announced that it was going to officially end support for its well-liked computer operating system, Windows 7, effectively forcing them to upgrade or use a system ripe for cyberattacks.

People were not happy— for huge numbers of users, there was simply no need to upgrade and relearn their system — but the company was committed. The transition process wasn’t smooth.

First, in 2016, the company announced some restrictions to back-end support. It changed that to ‘no new updates’ starting on July 17, 2017. User protests amplified, so it delayed implementation of that policy until sometime in 2018. When its constant exhortations about the need to switch to the new OS did not quell dissatisfaction, the company did a complete about-face, claiming it would continue to support the operating system for the “foreseeable future.”

That ‘foreseeable future’ lasted a little over a year, to January 14, 2020.

Now, Microsoft is dancing a similar jig, this time shutting down support for Windows 10 (effective October 14, 2025). Unlike the transition from Windows 7 to 10, which arguably offered significant advancements in efficiency and compatibility with hardware advancements, the motivation to shift from Windows 10 to 11 appears to have far more to do with revenue share than quality or security. Ben Caddy and Kieren Jessop, writing for Canalys, estimate that roughly one billion PCs will be affected globally.

At its release, Microsoft championed Windows 10 as the future of the company. The head of the Windows and Devices Group, Terry Myerson, told Tom Warren of the Verge in July of 2015:

There’s no one working on a Windows 11, but there’s a group of people working on some really cool updates to Windows 10.

Warren spoke to several other Microsoft developers and officials. From those conversations, he concluded:

If I’ve learned anything from speaking to the team building Windows 10, it’s that Microsoft is taking user feedback very, very seriously. Everything Microsoft is making — from the Xbox to phones to HoloLens — is based on Windows 10. It’s not just the foundation of this operating system, it’s the future foundation of the company. Microsoft doesn’t have a Plan B for Windows, and it’s proud of the fact.

Evidently, money talks louder than principles or pride. Just six years after the claim that ‘no one is working on Windows 11’, the company released… Windows 11! And now, only four years after that, Microsoft is wholly abandoning its so-called future foundational product, while paying little heed to user feedback along the way.

Forcing Windows 11 on people is, it seems, part of a planned “refresh cycle” for a market struggling to keep pace with an influx of other device types. (Don’t be deceived by this characterization; the company still netted $88.1 billion in profits in 2024). The thinking is that if people must upgrade to Windows 11, they will either have to buy new machines or engage in other conduct that will earn Microsoft revenue.

Richard Speed, of The Register, contends that the comparative disdain customers hold for the new operating system is a large part of what is prompting the company to withdraw its support of the previous one:

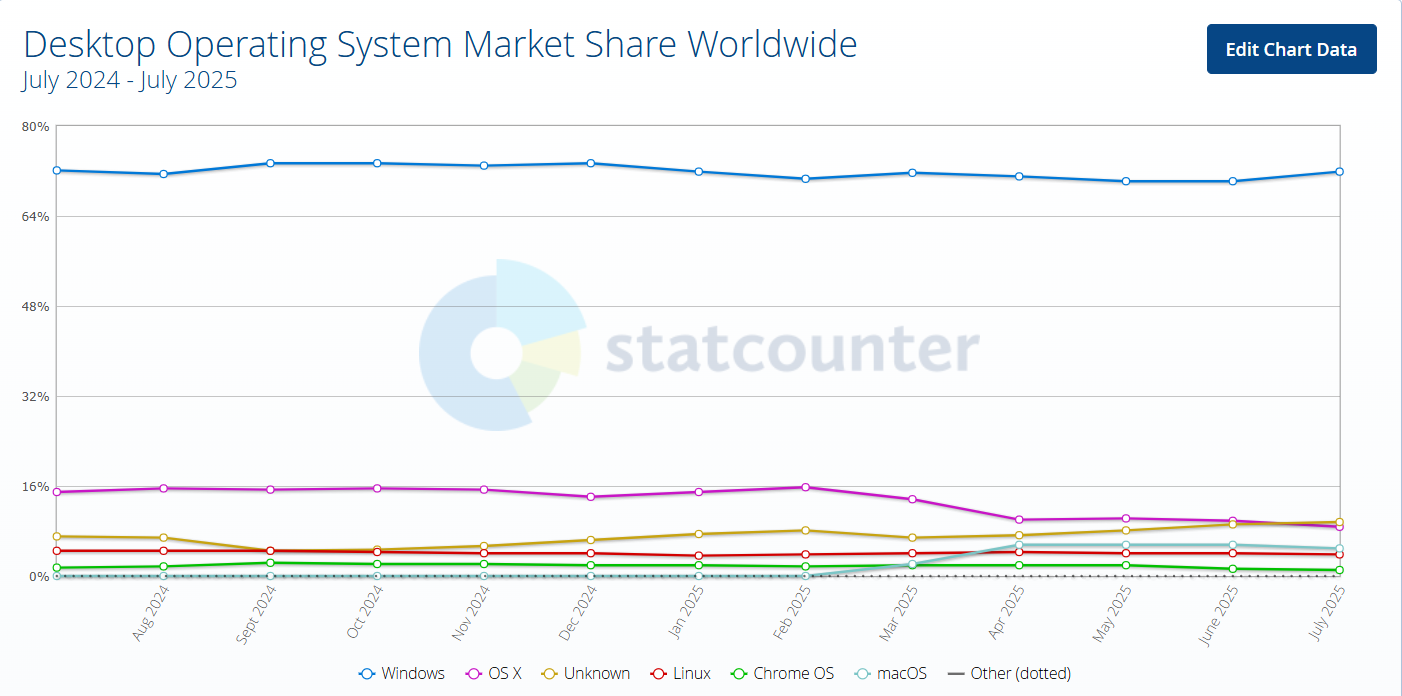

The problem isn't so much the well documented complaints over Windows 11's hardware compatibility requirements… but rather the increase in the market share of Windows 10. One theory is the earlier, higher numbers logged for October [of new Windows 11 users] were partially down to users who were "trying out" Windows 11, but then decided they did not like what they saw, and went back to Windows 10.

Put differently, users have shown a preference for Windows 10 even after trying the new version, but Microsoft needs to please its insatiable shareholders, so it is going to force users — er, ‘customers’ — into Windows 11 whether they like it or not. If they want to avoid it, they will pay up regardless.

In corporate speak, a ‘win-win’.

The ‘seamless’ upgrade

Microsoft cheerfully claims on its Q&A page, “Upgrades to Windows 11 from Windows 10 are free.”

But there are a few “buts.”

Key among them is that to upgrade your current Windows 10 PC it must have Trusted Platform Module (TPM) 2.0 installed. TPM is a chip that conducts various security functions. One cannot just convert an inferior version into 2.0; it is an entirely new piece of hardware. For people with older computers, this may be a problem.

Microsoft required manufacturing partners to include TPM 2.0 in all new devices starting in 2016, but Avram Piltch at Tom’s Hardware pointed out in 2021, that “many current motherboards come with TPM disabled by default and some recent high-end chips don’t have it on board.”

The average age of a personal ‘installed base PC’ in 2022 was about 4 years, according to Stat Investor. That means that a large number of people will still have PCs even in 2025 that are not compatible with the upgrade requirements for Windows 11, in many cases because they cannot afford a new machine. (Windows 10 held a market share of 62.7% as of December 2024).

The rest of the technical requirements should be less of a problem for most computers under ten years old (unless the user owns a home-built computer), but there are other issues. And here is where people are going to get really annoyed.

For starters, logging onto Windows 11 for the first time requires the opening of a OneDrive account. A OneDrive account allows Microsoft to track much of what you do on your PC if not configured to stop it. Not to mention, it raises the potential of permanently locking users out of their own content, sometimes for unknown reasons. OneDrive gives you some cloud storage and a few other trinkets in return.

If you don’t like the company breathing down your neck, you can evade this step by establishing a local account, but Microsoft is making it more and more difficult to do with each new build release.

To illustrate, to set up a local account on Windows 11 builds released after April 2025, you have to input the command, start ms-chx:localonly, into the command terminal, then follow a bunch more steps. If that feels daunting, then you understand what Microsoft is up to (nonetheless, if you care to try, see this article by Piltch). The instructions will probably change with the next series of builds as Microsoft continues to close this loophole.

So, I guess technically speaking, a OneDrive account is not a requirement (for now)… as long as you don’t intend to use a PC for certain things people normally do. Using Microsoft Office products (i.e. Word, PowerPoint, etc.), for instance, will require a OneDrive account. This is because the license to use MSOffice — now called Microsoft 365 — is stored there, and only there (in the newest versions). Without a OneDrive account, you will have to find a ‘cracked’ version of the Office product you want to use — if those things still exist (note, I am not recommending this as it is probably illegal).

A second problem is that if you want to use your OneDrive account to migrate to a new machine, you will almost surely have to pay for the service. Abhishek Mishra, at Windows Latest, writes:

[T]he system backup feature… can save and migrate your system settings, apps, preferences, and personal files to another PC. All you need to do is enroll the device in the backup and then ensure everything is backed including personal files and folders.

But then he points out the catch: “OneDrive’s free tier has a storage cap of 5GB, and that surely cannot accommodate everything.”

To put 5GB in context, a Samsung Galaxy S23 cellphone has 128GB of storage; an iPhone 16 can reach as high as 2TB (roughly 2,000GB) in the Pro Max. The Dell HP Prodesk 400 G1 PC, first released in 2013, has a 160GB hard drive. Most photos taken with average cameras use roughly 3 to 5MB of storage per image, while videos consume 150 to 400MB per minute. Apps can occupy 2GB (or even more, including cached files).

Thus, a person who has more than two apps and a handful of videos or a few hundred photos on their PC are going to exceed the space allowed under OneDrive’s free tier. The computer on which I am typing this article, for example, has used about 350GB of storage for non-system data, with apps comprising nearly one-third of that. I have a single game on my system; it takes up 63GB of space, or more than 12 times the space available on OneDrive’s free tier.

Yes, it is possible to migrate without OneDrive by using an external storage device. But Microsoft knows this is highly inconvenient. Not only does it require you to buy such hardware, but the copying and transporting may take hours depending on the volume of data. Plus, any hiccups will have to be resolved manually by the user.

If convenience is the deciding factor, then setting up — and paying for — a OneDrive account is the obvious choice, but putting all this data onto a company’s cloud comes with risks. While many people fear being ‘hacked’, the reality is that the overwhelming majority of breaches occur on company infrastructure, not personal computers. Microsoft is no exception.

Credit: IS Partners, LLC

Nefarious actors have successfully targeted Microsoft numerous times, including OneDrive itself. In June of 2023, hackers (possibly from Russia) “likely used rented cloud infrastructure and virtual private networks to bombard Microsoft (OneDrive) servers from so-called botnets of zombie computers around the globe.”

That was just one of 10 reported successful attacks committed against Microsoft assets since 2020. (It is estimated that nearly half of all data breaches aren’t reported to any authority, despite legal requirements to do so in many cases, so who knows how many Microsoft has truly faced). The January 2021 Exchange Server attack alone affected tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of servers worldwide.

Depending upon what you do on your computer, it might possess a great deal of private information (think tax returns, bank statements, or downloaded porn). Dropping it into a company’s cloud not only exposes it to potential theft by hackers, but also to third-party purchasers, some of unknown repute and some that are known, but are not good.

Given that there is very little regulation in this sector in the US, and Europe’s GDPR is weak and becoming weaker, there is no telling what pieces of your information may one day land somewhere that you would prefer they didn’t.

Ongoing Enshittification

In my writing, I have often used Cory Doctorow’s term, enshittification, because no one has better distilled the 21st century into a single word. In short, here is how the good Doctor(ow) explains it:

[H]ow platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

Microsoft is doing precisely that. The likeability of the user interfaces between Windows 10 and 11 may be a matter of user preference (though, Windows 10 is unquestionably better), but there are specific metrics that prove the company is gouging users for money with little of quality offered in return.

Perhaps foremost, Microsoft itself does not appear to believe that Windows 11’s security is so much better that switching is critical. After all, a user can purchase continued support as a (paid) subscription. If you choose to link your Windows 10 OS to a OneDrive account, then continued support is free (you’re just giving away your privacy instead of cash).

Some IT analysts do not see a considerable difference in the level of individual security between Windows 10 or 11 either, based on the average user’s needs. Techbloat writes:

For most users, both operating systems offer a comparable level of protection. Advanced features in Windows 11, such as enhanced hardware-based security, might be underutilized by the average user, making the practical difference negligible.

Neil J. Rubenking at PcMag tested Windows Defender—the security architecture used in both Windows 10 and 11. He concludes:

We used to say Windows Defender isn’t good, but it’s better than nothing. Now, we're willing to say Microsoft Defender Antivirus is good, just not great. Some of its lab test scores are excellent, though it took a while to reach this point, and its scores in our hands-on tests are nothing to write home about. The best free antivirus utilities give you more protection, and they earn great scores from independent testing labs.

Four years before that, Alex Vakulov at Server Watch stated:

[W]e analyzed the claimed security features of Windows 11. In our opinion, the word “new” cannot actually be applied to them. There are no significant innovations (like Windows Defender in version 10).

It seems little has changed.

Aside from limited gains in security, Windows 11 has something called “badges,” or notifications about various apps running on the system. Sometimes, these ads (let’s call them what they often are) mimic true system warnings, thereby frightening some users into purchasing Microsoft services they may not want or need.

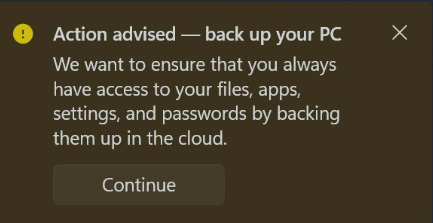

Sample ‘badge’ wherein Windows tries to persuade the user into upgrading their OneDrive account.

Windows 10 actually introduced badges, but did not employ them at anywhere near the same annoying frequency or with the same degree of deception as Windows 11. If the recent history of virtually every service is any indicator, expect these ads to become even more irritatingly intrusive in future iterations of Windows operating systems or with upcoming Windows 11 updates.

Copilot is another lousy feature that Microsoft has jammed into Windows 11’s infrastructure. It is an “AI assistant” program—basically a fancier version of Notepad’s, Clippy. Fancier, but not better, as some argue.

Clippy, the critically endangered paperclip.

There are a bunch of reasons why integrating artificial intelligence into operating systems is disliked by users—it’s invasive, error-ridden, and resource draining, to name a few. Moreover, it learns from what the user inputs. Hence, it should issue warnings like these:

Credit: Auslogics

Unsurprisingly, Copilot is crashing and burning. In an executive meeting in March or April of this year, Microsoft CFO Amy Hood revealed that ChatGPT gets 20 times more weekly users than Copilot, a number that has since doubled to 40 times as many, which is funny given the company’s huge investment into OpenAi, ChatGPT’s parent company.

Fortunately, you can disable or even delete the Copilot app. And that’s a good thing because Microsoft—like practically all companies developing AI—is rather vague about what it does with your data associated with the use of Copilot, including prompts, responses, and interaction logs (records of when and how Copilot was used). To highlight this point, “Microsoft states that prompt and response data may be retained for up to 30 days for service improvement purposes.”

Service improvement purposes — The ubiquitous catchall for tech companies to do what they want with user data.

I suspect that before long, it will become impossible to delete or disable Copilot, should Microsoft stubbornly insist on trying to keep it afloat. There is a saying that “if the item is free, the product is me.” Remember that if you decide to try it out (though the paid versions will also benefit the company from your data).

Few steps forward, many steps back

Reasonable minds can argue over which Windows operating system they like better. Despite the points made in this article, there are elements of Windows 11 that improve upon 10. But this doesn’t exclude it from enshittification.

This is because while the virtue of the differences are debatable, the requirement to use the new OS will not be. Once back-end support is gone, only a rare few will have the skills needed to continue operating securely with Windows 10. Everyone else will be forced into upgrading (or switching to a different OS altogether though, again, Microsoft has made even this difficult for average users).

To Microsoft, it is irrelevant what a huge number of its customers prefer. The company — and only the company, apparently — will decide what works for them. Gone are the days of a product selling based on its merit or popularity. Today, it is extortion powered by monopoly. Without competition there is just no need to bother about customer satisfaction.

Can you evade Microsoft’s efforts to force you to capitulate? Yes (again, for now). But the fact of the matter is that it requires a great deal of effort to do so. Few reading this will bother. And who can blame them? Our time on this planet is finite, and numerous things compete for it.

The problem is that apathy is precisely what companies like these depend upon, but the longer it persists, the sooner it won’t matter. They are actively working to make free will a thing of the past. After all, when there are no meaningful choices, there will be no need to retain the ability to make them.

At least then they will no longer need to inundate us with crappy ads.

A long, well written and documented article. I used Windows 7 for years and got along passably well, although it seemed there were interminable if infrequent problems. I have not plugged in my PC for 7 or 8 years and get along just fine with an iPad and an iPhone. Hardly ever a problem and virtually no learning curve. I don’t miss Microsoft at all.