Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Sometime in the year 1903, a female Bengal tiger suffered a gunshot wound from an undocumented encounter with a human somewhere in western Nepal. The wound caused significant damage to the tigress’ mouth, including destroying two of her canine teeth. Such a devastating loss of a crucial tool in the tigress’ hunting apparatus probably prohibited her from taking down her usual prey—the large, and dangerous water buffalo. Driven by the instinct to survive, and the insatiable need for large prey to fuel the tigress’ impressive body (female Bengals weigh an average of 400 pounds or 181 kgs), she turned to the weakest available large prey dotting the Mahakali Zone of Nepal—humans.

A Water Buffalo in Chitwan National Park, Nepal; credit: RoyandIngrid

From 1903 to 1907, the Champawat Tigress (named for the place she later gained widespread notoriety) began killing and eating humans in Nepal, mostly women and children, at a rate of a little more than one a week. Contrary to common belief, tigers do not hunt solely at night. They are opportunistic hunters who rely on stealth, lethal strikes, and enormous power. With the ability to sprint up to 35 mph (56 kph), and leap as far as 30 feet (9 m), these big cats wait in silence until prey is just close enough, then they spring. Using their massive bulk, they knock their victims off balance while simultaneously targeting the neck to either instantaneously crush the windpipe, or slowly suffocate the prey by applying a bite force of 1,050 psi. The humans in Mahakali Zone stood little chance.

A Bengal Tiger in Chitwan National Park, Nepal; source &beyond

Amidst the ongoing killings, the people grew fearful of coming outside, even during the day. Eventually the villagers asked the Nepalese army for assistance. At first, only private hunters came to help. None of them could locate the tigress. The army came to the area in 1907; by then at least 200 villagers had succumbed to the tigress. Despite arriving with a large force, the army did not successfully track the tiger, let alone capture or kill it. Nevertheless, their presence did manage to drive the tigress over the border into India. There, across several dozen villages, she continued her feeding. After killing more than 200 villagers over dozens of square miles, authorities requested a new call-to-action.

India in 1907 was under British rule. The area of India that the tigress migrated to, the Kumaon area, was part of the present-day state of Uttarakhand. Great Britain had acquired the area under the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816. The British set up an administrative unit, called the “Patwari Halka,” which collected taxes and handled issues of law and order. The Patwari Halka fell under the governing office of the Nainital, which requested assistance from the British government for its tiger problem. In response, the British commander of that area of India called upon Colonel James Corbett. Known in India for his status as an exceptional hunter of “dangerous game,” Corbett demanded two conditions before he would accept the job. He wanted the government to rescind its current award for anyone who captured or killed the tiger, and he asked for local regulars (soldiers) to be withdrawn from the area. His reasoning: he did not want to be viewed as a trophy hunter for this expedition, and he did not want to risk getting “accidentally shot” by others seeking the reward. The government quickly agreed.

Corbett understood that the tigress’ actions exhibited unusual behavior. He noted that tigers focus on humans almost always out of some deficiency in health—caused either by age or injury. In the beginning of this article, I mentioned an “undocumented” encounter. People in those days simply didn’t report incidents involving wild animals most of the time. Corbett would later learn he had speculated correctly about the likelihood of this tigress’ health, even though he had no knowledge of the human encounter that had seriously injured her. Nevertheless, for this hunt he would not proceed with any less caution. Indeed, if she was a wounded animal, it also meant she was a desperate one… and therefore more dangerous, if anything. Still, before Corbett came along, no one had considered the possible reasons why this tiger turned to targeting humans.

Unsurprisingly, even in a reduced-capacity state the tigress proved to be a challenging quarry. Just one day after Corbett’s arrival, she killed a 16-year-old village girl. Until then, Corbett had been unable to locate the tigress. This kill, however, proved her undoing. He later wrote, “The track of the tigress was clearly visible. On one side of it were great splashes of blood where the girl’s head had hung down, and on the other side the trail of her feet.” Upon following the trail of carnage, Corbett found no easy time of finishing her. In fact, she nearly ended him first, having successfully concealed herself until the last seconds as they neared each other. Still, he prevailed and the scourge upon the Kumaon area ended. It was only during his post-mortem exam did he confirm his earlier suspicions about the reasoning behind the big cat’s behavior. The exam uncovered the previous bullet-inflicted wounds to the tigress’ face.

This is a sad story for everyone involved and it is therefore difficult to hold any ill-will toward anyone. The tigress merely did what she needed to survive. The villagers did the same. Corbett, for his part, seemed to earn his career as a hunter specifically of man-eating animals. He lived in a time when people and large predators shared a lot of space (humans have since primarily won that war—however a pyrrhic victory that it may be), so people of his skillset were desperately needed. Corbett later reported that the creatures he hunted had collectively killed around 1,200 humans. While this may have been an exaggeration, and while it is also possible he did hunt for sport but cultivated a different public persona, Corbett did many good things that provide evidence supporting the notion he held beneficent intentions. For example, he played a large part in establishing India’s first national park in the Kumaon hills—one that to this day continues a conservation program for tigers. He also trained troops in WWII how to survive in the jungle.

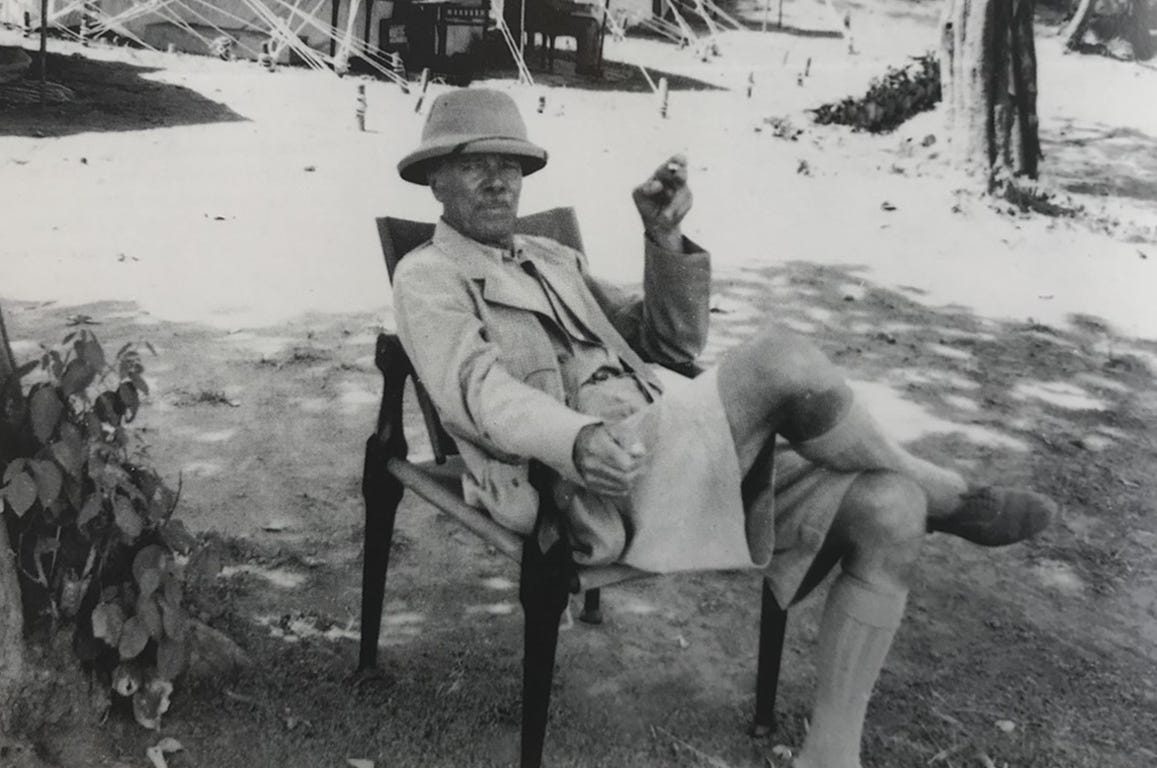

Lieutenant Colonel Jim Corbett (1937); credit: The British Library Oriental and India Office Collections

The Champawat Tiger is not the only beast to pursue humans as result of a situation those very humans contributed to creating. An Amur (a.k.a. Siberian) tiger famously stalked and killed Russian poacher Vladimir Markov after Markov shot the tiger and stole her kill in 1997. (The Moscow Times calls Markov a “beekeeper,” not a poacher, though it later concedes he took to poaching because of poverty). In any case, after the shooting and theft, the tiger stalked Markov over the next several days, at one point even trashing his hunting cabin while the poacher was off in the woods. Whatever his true purpose might have been—beekeeping or poaching—Markov unquestionably shot the tiger at least once. In response the tiger terrified him for two days before finally killing him and leaving nothing but the stumps of his feet in a pair of boots.

TSAVO Lions

For nine months in 1898, two male lions in the Tsavo region of Kenya earned a terrifying reputation as man-eaters, ultimately dispatching up to 135 people (reports vary widely on the figure, but no one disputes the level of terror). The lions targeted humans working on the construction of a railway bridge. Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson, a British military officer, who oversaw the project inherited the problem just days into his tenure. Hunting at night when the camp was quiet, the lions used cunning and craft to snatch defenseless workers from their tents, before dragging them off, killing, and eating them.

Lions are known to target humans more often than tigers, which may simply reflect the frequency of encounters. Nonetheless, lions repeatedly feasting on humans, especially in the same encampment, illustrated abnormal behavior leading many over the last century to speculate on the cause of that behavior. Larisa R. G. DeSantis and Bruce D. Patterson (not sure if there is a familial relationship with the colonel) conducted a detailed study on the Tsavo lions and another man-eater, the Mfuwe lion who ravaged Zambia in 1991. They concluded the following:

Man-eating, or consumption of humans as women and children are often victims, has occasionally been a dietary strategy of lions and other pantherines… Evidence of dental disease is quite clear in two of the three man-eating lions. One lion (the first Tsavo man-eater), with a broken canine, developed a periapical abscess and lost three lower right incisors. The pronounced toothwear and extensive cranial remodeling suggests that the lion had broken his canine several years earlier. The second Tsavo man-eater had minor injuries including a fractured upper left carnassial and subsequent pulp exposure, although these types of injuries are fairly common and were unaccompanied by disease. These injuries may have been decisive factors influencing their consumption of humans.

Two of the three man-eaters had serious infirmities to their jaws and/or canines, potentially hindering consumption of hard food items and/or reduced prey handling ability (prey are seized and held with teeth and jaws). Tooth breakage per se does not produce dietary shifts as most older lions display some sort of wear or breakage to their dentition. However, dental disease is another matter, and incapacitation via an abscessed or a fractured mandible may have prompted the Tsavo lion to seek more easily subdued prey. Infirmities such as these were frequently associated with man-eating incidents by tigers and leopards in colonial India. [Citations omitted]

Unlike the Champawat Tigress, no one knows how the Tsavo lion initially suffered tooth and mandible damage leading to severe dental disease. But that dental infirmity may well have exacerbated the carnage, especially in light of the ample source of largely defenseless prey (humans). DeSantis and Patterson noted that the lion with severe dental damage ate nearly double the number of people as his companion, but that “the second Tsavo lion may have simply shared meals through his social bonds with the first man-eater.” Furthermore, dental microwear texture analysis (DMTA) indicated that the humans merely supplemented an otherwise diverse diet.

To sum it up, one lion preyed on humans as a more prolific part of his diet because of injuries and availability. The fraternal relationship between them led the other to simply join suit, thereby doubling the carnage and terror. Collecting in large numbers to build the bridge right in the middle of lion territory simply put hundreds of humans in easy reach. In the end, the lions both suffered the same fate as the Champawat Tigress—they were shot to death, in this case by Colonel Patterson.

Human Responsibility

Humans have spent the better part of two centuries infringing on the territory of these (and many other) majestic creatures. Every death that results from the inevitable encounters that occur in this conflict of space is a tragedy—whether human, animal, or both. But, there is one key takeaway. Only one side has the power to properly address—if not fully rectify—the situation. Back in the late 19th or early 20th centuries I can understand the instant reliance on violence as a solution. In 2023, however, I would like to think we have evolved beyond that. Humans have a responsibility to find solutions suitable for every living thing involved. Recently, reports surfaced of orcas “attacking” boats. At least, that’s how many media portrayed it. What I saw, though, was a highly intelligent species, made up of close-knit families—even whole communities—who find themselves pushed closer and closer to the brink of extinction. A situation which they have determined has left them little choice but to engage in violence to preserve their very survival. If after at least 100 years our species cannot comprehend a better way for all of us—humans, orcas, tigers, etc.—to move forward in some form of harmonious existence, then we have no right to think of ourselves as superior.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

Read below for how conservationists have worked to preserve the snow leopard population.

Amazing and educational and very entertaining read. I really enjoy the plethora of different things you have written. Keep them coming.