A Buddha Air ATR 42–300 at Pokhara Airport. The ATR is among the most commonly used commercial aircraft for domestic flights in Nepal. Credit: Solundir, CC BY-SA 4.0

Nepal has long held the reputation of an inherently dangerous place to fly. Natives, tourists, and other foreigners have expressed this concern to me on more occasions than I can count — and I fly there a lot. Hundreds of times, in fact, both in and out of the country and domestically. Their reservations are not without some merit, but the answer to whether it is safe to fly there is highly dependent on the context.

A very brief history

Aviation as a commercial industry in Nepal started in 1958. Its centrally-owned airline — Royal Nepal Airlines—became an official member of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) two years later. In 1992, the domestic aviation sector opened to private companies. Over the next decade, aviation in Nepal generated a mostly negative image and has struggled to improve thereafter.

Nepal’s Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation established a unit to “monitor the work performance, leakage and irregularities of the Civil Aviation Authority and the Royal Nepal Airlines Corporation” in 2003 to address increasing numbers of complaints. Many believed that conflicts of interest and corruption were the primary causes of the industry’s problems.

Media in Nepal did not seem to find that oversight effective. The Himalayan Times and other outlets started regularly reporting on ostensibly rampant safety issues in 2005.¹ They have continued to do so ever since.

In 2013, the European Union (EU) imposed a blanket prohibition on Nepal-owned airlines flying into its airspace. The ban was based on deficiencies found during inspections of airliners while at European airports as well as issues with Nepali regulators.

Criticisms became more poignant following several fatal incidents over a six-year period starting in 2018. Following those incidents and the Nepali government’s failure to address certain systemic issues, the European Commission elected to continue its ban on December 13, 2024.

Given this introduction, it seems the answer to the headlined question is obvious. It must be unsafe to fly in Nepal.

But the reality is more complicated and depends on several factors. So, if you are considering a trip to one of the most beautiful destinations on Earth, but you are concerned about flying there, this article is for you.

Aerial view of Tribhuvan International Airport (Credit: magar sandy, Public Domain)

Flying into or out of Nepal

There is a critical component to evaluating the safety of a flight involving Nepal. That is whether the determination involves flying into (or out of) the country or flying domestically.

On the former, Nepal has endured four fatal accidents between 1992 and the present. It is perhaps because the two worst incidents happened just two months apart resulting in 280 fatalities that there is some belief that international flights there are dangerous.

The first of those incidents involved Thai Airways Flight 311. It occurred on July 31, 1992, and was attributed to a minor malfunction with the plane’s flaps, as well as a series of miscommunications between the pilots, and between the crew and air traffic control (ATC).

Fifty-nine days later, all 167 souls onboard Pakistan International Airlines Flight 268 were killed. Investigators determined that the pilots’ errors on approach led to the aircraft colliding with a hillside.

In those days, approach plates were physical not digital charts. Flying into Kathmandu requires a descent of precise steps to avoid the nearby high terrain. Pilots unfamiliar with the approach could more easily misapprehend the proper path back then. Both Thailand’s and Pakistan’s aviation programs have since received much better safety ratings.

In 1999, an Indian-German-owned cargo flight lost all five crewmembers on departure from Tribhuvan Airport (TIA) in Kathmandu. The investigation revealed that a combination of a loss of power and a deviation from the Standard Instrument Departure caused the crash.

Finally, on March 12, 2018, US-Bangla Airlines Flight 211, enroute from Dhaka, Bangladesh, crashed at TIA. Fifty-one of the 71 people aboard lost their lives. The final report concluded that acrimony on the flight deck was the primary source of the crew’s loss of situational awareness and poor decision-making.

Four incidents in 32 years comprising 336 fatalities is not a gold standard, to be sure, but it is also not evidence of a serious problem, especially given that two-thirds of those fatalities happened back-to-back, decades ago.

Moreover, the issues leading to those accidents have largely been rectified, such as ensuring standardized communication and providing detailed and accurate approach and departure standards and charts. The 2018 US-Bangla Airlines Flight had more to do with problems on the flight deck than Nepal’s aviation procedures. And neither pilot was Nepali.

Therefore, visitors should not worry over the safety of flying into or out of Nepal. As the primary entry point into a mountainous country, four fatal incidents in nearly four decades is not especially anomalous.

Your author standing in front of the wing and propellor of a Shree Airlines Dash-8 in Pokhara, Nepal (December, 2023).

Domestic flying

The safety of flying within Nepal is mixed, and factors such as the flight path, destination airport, and type of aircraft deeply affect the analysis. Three recent crashes have exacerbated ongoing concerns about safety:

A Tara Air DHC-6–300 crashed in May of 2022 on a domestic route to Jomsom, killing 19.

About 7 months later, in January 2023, everyone aboard Yeti Airlines Flight 691 was lost (72 passengers and crew) when the plane went down just short of the runway at the newly-minted Pokhara International Airport.

In July 2024, a Saurya Airlines plane skidded off the runway at Tribhuvan Airport, killing 18 of the 19 people aboard.

Since 2010, 258 people have died in 13 domestic air crashes in Nepal (this number excludes helicopters, experimental, and non-commercial flights). Most of Nepal’s aviation accident deaths involve very small aircraft — those carrying 30 or fewer passengers and crew. Regardless, its accident rate among these types are comparable or, in some cases, better than places where the same kinds of aircraft are routinely used.

For example, Nepal and Alaska host similarly rough terrain and weather, and domestic flights use many of the same aircraft types. Alaska’s population is considerably smaller; in 2020 it was 733,391 compared to around 29 million in Nepal. The average number of tourists per year to Alaska is similar to Nepal’s annual totals. Despite these parallels, Alaska’s air crash fatality rate is far worse. The state had 10 fatal accidents in 2019 alone, and 50 fatal accidents between 2015 and 2019.

Lukla Airport, 2023. Photo courtesy of Professor Michal Apollo.

The challenge is the topography

The 2019 Aviation Safety Report produced by Nepal’s Civil Aviation Authority (CAAN) noted that 74% of fatal flights resulted from Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT). A CFIT accident occurs when there is nothing mechanically wrong with the aircraft and it is under pilot control, yet it unintentionally collides with the ground, water, mountain or other obstacle.

CFIT accidents tend to happen when pilots lose situational awareness, particularly the position or geographic location of the aircraft. Sudden changes in weather often lead to CFIT incidents, especially when flying under Visual Flight Rules (flying by sight, not instruments).

In Nepal, many domestic airports are situated in places where the surrounding terrain can exceed the absolute ceiling of aircraft, thereby limiting escape maneuver options if things go awry. These areas are subject to swiftly changing weather conditions that can make flying, takeoffs, and landings quite challenging.

The physical layout of airports adds to the complexity because most are designated as Short Takeoff and Landing (STOL). Navigating STOL airfields requires a great deal of attention and skill:

Pilots must be adept at precise speed control, understanding the aerodynamics of high-lift devices, and executing manoeuvres within confined areas, all while contending with potential obstacles and variable wind conditions.

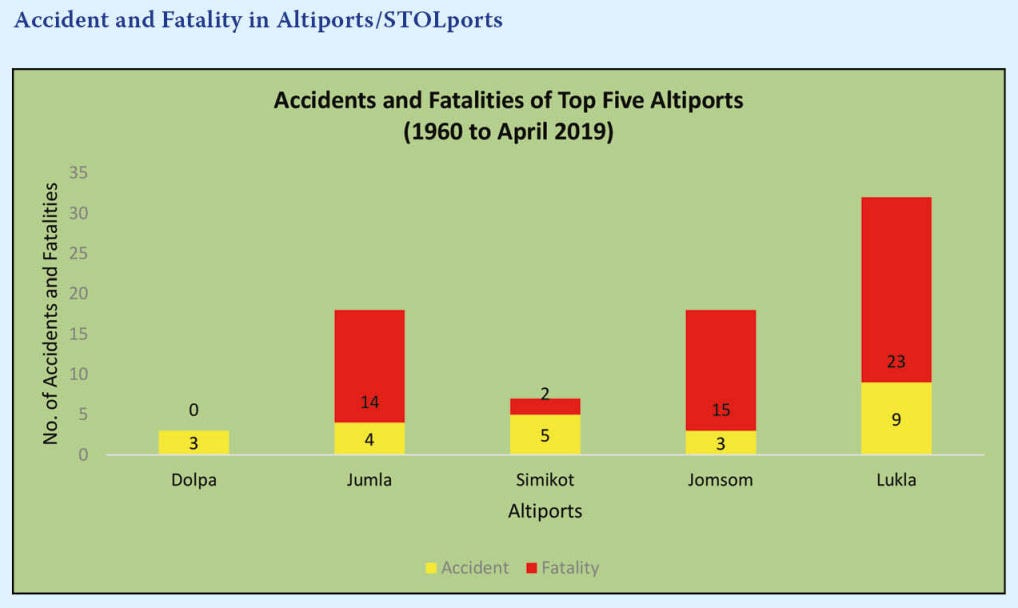

STOL flying in Nepal has resulted in 49% of aviation fatalities between 2009 and 2018. The most infamous airport of this type, Lukla (a.k.a. Tenzing-Hillary Airport), accounts for more fatalities than any other, with Jomsom and Jumla ranking near each other in second and third place. All three are in extraordinarily remote locations.

Source: CAAN 2019 Aviation Safety Report

Lukla sits at the top of the list due to a number of factors: its high elevation (9,337 feet), very short, upward gradient runway, and lack of a go-around procedure (it sits on the side of a mountain). Without the possibility of a go-around, the pilot has no choice but to land once committed, even if the conditions suddenly render that a perilous decision.

None of Nepal’s STOL airports have a working Instrument Landing System (ILS), which means pilots must conduct operations visually — a daunting task in the tumultuous weather of the Himalayas. It is common across the world for STOL airports to lack ILS, so Nepal is not in any sense an outlier.

You can fly safely on domestic flights in Nepal

There is a critical point worth emphasizing here. Tourists who visit Nepal can enjoy the majesty of the Himalayas without climbing aboard small aircraft and flying into potentially precarious airports. The most frequent domestic flight travels between Pokhara and Kathmandu using Franco-Italian made ATRs. Pokhara provides an easy entryway to the Himalayas (or some great pictures from the city itself for the less adventurous).

I mean, this is just the view from the airport. (photo by author, 2023)

The crash at the airport in Pokhara in 2023 was the first (and only) incident involving an ATR on a commercial, domestic flight in Nepal. Furthermore, the causation was determined to have been pilot error associated with the newness of the aerodrome, which went into operation just two weeks before the accident. Neither pilot had much experience with the new approach paths and seemed distracted by them in the moments prior to impact.

If you wish to learn more about that accident, I wrote two in-depth analyses of the crash. You can find them here:

The Final Report - Yeti Airlines 691

Image of the accident plane taken well before its demise. Credit: TMLN1234, CC BY-SA 4.0

Mile-per-mile, Nepal’s skies are far safer than its roads and are comparably better than other places in the world one can fly. Nonetheless, dependent as it is on tourism — of which aviation is a significant part — Nepal must work on fixing the public perception of its flight industry.

Improving a bad reputation

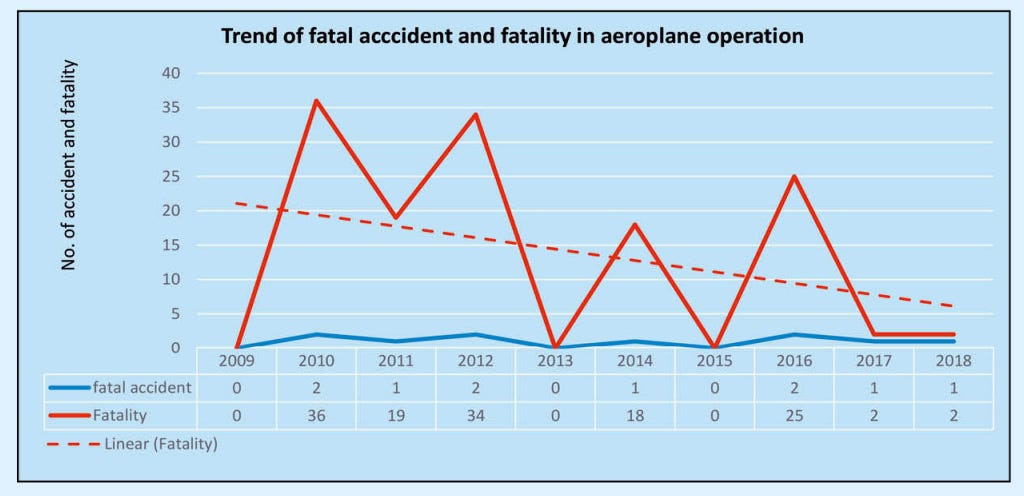

Despite the high profile setbacks in May 2022, January 2023, and July 2024, Nepal has pursued many improvements in the last two decades. As a result, it showed an overall drop in fatalities between 2009 and 2019.

The incidents in May and January seemed to be caused primarily by pilot error, the latter of which was exacerbated by flying into a new airport on a new flight plan. The crash in May can be blamed in part on the pilot’s choice to fly into weather about which he expressed concerns ahead of time. (You can see my report on that event here).

Source: CAAN 2022 Aviation Safety Report

One measure CAAN has implemented is its hazard reporting system. This allows pilots to report specific dangers that can then be forwarded to other flights or to regulators. In 2021, CAAN received 986 reports identifying potential hazards in organizations (43%), technical issues (20%), environmental dangers (18%), and others. This voluntary reporting system is an excellent measure to address potential problems and is used in other major markets, including the USA and Europe.

Another program, the Safety Management System (SMS), is also now in place, although its effectiveness and compliance numbers leave a lot of room for improvement, according to CAAN reports. The SMS is essentially a written plan that defines and enforces an organization’s culture toward safety in all elements of its operations. Despite some lag in the implementation of the SMS, Nepal’s overall State Safety Oversight Capability rating exceeded the ICAO industry target by 10.1% in a 2022 audit.

CAAN’s National Aviation Safety Plan for 2023 to 2025 also indicates significant positive potential in other areas. This plan addresses issues such as CFIT mitigation, Loss of Control in Flight mitigation, reduced Runway Incursions and other matters that are acutely problematic in Nepal.

Among the proposals are to require Terrain Awareness and Warning Systems (TAWS) in more aircraft, enhance regulation of the use of Ground Proximity Warning Systems (GPWS), ensure timely updates of Electronic Terrain and Obstacle Data (eTOD), and increase training requirements in many critical procedures, among many other items. At the time of this writing, it is not possible to evaluate the efficacy of these proposals.

What about the EU ban?

Perhaps the greatest impediment to Nepal’s aviation sector’s improvement is its regulatory structure. While serving as the national regulator for aviation safety, CAAN also runs two of the three international airports in the country: Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu and Gautam Buddha International Airport in Bhairahawa (now officially called Siddharthanagar).

The EU Commission commented in its report on November 23, 2022 that Nepal’s government should “revise considerations about the functional separation of the regulatory and services provider roles of CAAN, which is a longstanding issue.” It then stated that the adoption of a new regulation that will “ensure CAAN’s functional division” of regulatory and provider roles may lead the Commission to reassess the ban on Nepal flights into the EU [my emphasis added].

ICAO expressed the same concerns in its 2022 safety audit. There, it underscored deficiencies in Nepal’s national organization of regulation and accident investigations, both functions of CAAN. Its issue was that CAAN’s dual role as regulator and service provider can create conflicts of interest that hamper safety enforcement and proper investigation and reporting of incidents.

Unfortunately, the legislation required to enact the split has repeatedly stalled, with some believing that a “functional division” is altogether unnecessary. CAAN’s Director-General Pradip Adhikari stated in May of 2022 that the EU Commission has not demanded this action and that it hasn’t questioned similar arrangements in Bangladesh or Singapore. This recalcitrance has led one expert to state:

[F]or a country like Nepal, where corruption is widespread and institutionalised, reforms don’t easily happen. Nepal has consistently failed to abide by the reforms recommended by global aviation watchdogs.

The two largest political parties — the Nepali Congress and the CPN-UML — appear to recognize that failing to move forward on implementing some kind of reform that would satisfy ICAO is hurting the industry, but the legislation has languished since its initial proposal all the way back in 2007. Without some kind of regulatory reorganization, the EU ban is likely to continue, as evidenced by the vote to uphold it this past December.

If an airplane isn’t for you, there is always this option. (photo by author, taken near Pokhara, 2024)

The verdict

Flying commercial jets into and out of Nepal is pretty safe. The last major incident was in 2018, and was the result of poor cockpit performance. Neither the airline nor the pilots were Nepalese, so the incident arguably had little to do with the country’s aviation safety at all. It was an event that could have happened anywhere with an equally situated airline and crew.

The safety of taking domestic flights in Nepal is largely dependent on the destination and the aircraft. Trips to Pokhara or Bhairahawa are typically conducted in ATRs or De Havilland’s Dash, both of which have an excellent record in Nepal and internationally. Moreover, Pokhara and Bhairahawa airports both have sophisticated landing systems.

Traveling to remote locations is a little more tenuous and not necessarily good for the faint of heart. Aircraft in Nepal tend to fall below expected maintenance or equipment standards in correlation with their size. That is, as the aircraft gets smaller, its likelihood of it meeting safety standards decreases. Airports like Jomsom or Lukla are challenging enough without these deficiencies.

Even on well-maintained aircraft, these flights can be harrowing when the Himalayas decide to flex their climatological muscles. If you have never flown in something small like a DHC-6 Twin Otter, it might not be the best choice to challenge the world’s tallest mountains as your first endeavor.

With all this said, if you want to see some of the most stunning views the world has to offer, there is no better place to do it than in the skies among the mountains of Nepal.

Postscript

This article addresses flying in fixed-wing aircraft. Traveling the country in a helicopter is quite a different matter and requires more discussion than the space available here allows.

* * *

Note: I have recently joined a large project that will occupy substantial time. As a result, articles will only post once per week, on Saturdays, starting with this one.

If you enjoyed this article, consider giving it a like or Buying me A Coffee if you wish to show your support.