Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

The American justice system favors the rich and well-connected. People of influence receive special treatment as a matter of course. Sheldon Silver and Steve Bannon were two among many who were allowed to remain free while appealing their convictions, an option rarely, if ever, granted to the less fortunate. Politicians regularly see their convictions overturned on specious legal reasoning meant only, evidently, to protect the systemic bribery in the American political system, a perversion hefted on society by an abjectly corrupt Supreme Court. In the current “case of the century” —the prosecution of former President Donald Trump—courts have shown no end of tolerance for behavior that would have landed anyone else in pretrial lockup some time ago, the result of cowardly wrangling over issues of supposed free speech never considered for “lesser” defendants. So when yet another member of Congress finds himself in the crosshairs of justice, the American public can be forgiven for holding a high degree of skepticism that true justice will be meted out. Despite all of this, I am confident in predicting that George Santos is going to be enjoying a years-long prison sentence.

George Anthony Devolder Santos is a criminal fraudster who got himself elected to the increasingly corrupt and irredeemable Republican party’s seat in the US House of Representatives’ 3rd Congressional District of New York. Immediately upon assuming office his litany of lies came to the public light, but of course by then it was too late. For a brief reminder, here is what I wrote of his deceptions:

“Propensity to lie” is a meek way to describe Santos’ behavior. He is on-record saying things so easily disproved, that a more apt description might be “inept con artist.” During his campaign he claimed—all falsely—that his grandparents had survived the Holocaust, his mother died from complications related to September 11 in New York City, he received a sports scholarship for a college (he neither received the scholarship nor attended that college), that he worked at two major financial institutions, that he was robbed of past-due rent money (this lie was made in a sworn statement in an eviction case), that he employed four people who were killed in the Pulse Nightclub Shooting, among still others. In addition, he has been accused in several other apparent crimes, including defrauding a homeless vet, impersonating Kevin McCarthy’s staff member, and stealing scarves. Meanwhile, he also agreed to pay a fine and victim compensation for a fraud for which he was wanted in Brazil from 2008.

At the time of that writing, the federal government had already indicted Santos on thirteen charges including five counts of Wire Fraud, three counts of Unlawful Money Transactions, one count of Theft of Public Money, two counts of fraud related to stealing unemployment benefits (more Wire Fraud charges), and two counts of lying to the federal government. You can read that entire indictment here. Since then, the federal government levied 10 more charges on the outspoken conman. The latest crimes include Conspiracy to Commit Offenses Against the United States, Wire Fraud, False Statements to the Federal Election Commission (FEC), Falsification of Records to the FEC, Aggravated Identity Theft, and Access Device Fraud. You can read the superseding indictment here. For the record, I will repeat another statement from the last article that continues to ring true.

Of note, the above paragraph describes allegations made by the United States government that has yet to prove them in federal court. Given Santos’ propensity for lying and deceit, however, it is a strong bet that he will either plea or be found guilty.

Back in September, Politico reported that prosecutors had “asked the judge overseeing the case to delay a court hearing set for Thursday because ‘the parties have continued to discuss possible paths forward in this matter. The parties wish to have additional time to continue those discussions’.” At the time, two of Santos’s campaign aides also pleaded not guilty to various criminal charges. Many had speculated that the asked-for delay meant Santos himself sought a plea deal, despite his public protestations to the contrary. Instead, it appears prosecutors needed time to lock in plea and possible cooperation agreements with Santos’s co-conspirators. One of those co-defendants, Nancy Marks, eventually pleaded guilty to (a) wire fraud; (b) making materially false statements; (c) obstructing the administration of the Federal Election Commission (FEC); and (d) committing aggravated identity theft. Sam Miele pleaded guilty just a few weeks later to one count of wire fraud. Those pleas took place in late October or early November. In short, Santos’s co-conspirators both pleaded guilty to crimes related to Santos’s conduct. This is one of two very bad pieces of news for the imminent convict and former Congressional Representative. First, both aides almost certainly negotiated less prison time in exchange for testifying against Santos. Their testimony will nicely buttress the seemingly ample documentary evidence. But perhaps more significantly, in the face of an almost certain conviction, Santos had but one other card left to play to abrogate his chances of growing old and possibly dying in prison. That card has been revoked.

On December 1, 2023, the US House of Representatives voted to expel Santos from Congress. According to the Constitution, two-thirds of the House must vote to pass an expulsion, which currently comprises 290 out of 435 members. Upon the success of the vote, Santos left immediately. Think of it as an instant firing followed by a security escort out of the building. Congress expelled only five House members before Santos over nearly two centuries. Three of them, John B. Clark, John W. Reid, and Henry C. Burnett, all got kicked out for disloyalty related to their involvement with the Confederacy—a seditious army that waged a civil war against the country. The fourth, Michael J. Myers, had been convicted of bribery and the fifth, James A. Traficant, had been convicted of charges similar to bribery. Santos, though not yet convicted, was expelled related not just to his myriad lies during his campaign, but because of the abundance of evidence indicating he stole money from people including through ruses conducted through his campaign and Congressional office, among a series of other crimes.

What’s interesting in this case is that because Santos has not yet been convicted, his expulsion deprived him of a significant bargaining chip in the lead-up to his trial. Many American public figures—very wrongly in my opinion—use their position to procure generous plea deals when they are caught committing crimes. It manifests as an offer to step down in exchange for avoiding going to prison. Former Alabama Governor Robert Bentley (R), for example, faced accusations of using public resources to carry out and conceal an affair with his former top aide. Upon resigning, he was offered a sweetheart plea deal which allowed him to cop to two misdemeanor charges and avoid jail time. Lynda Bennett, a Republican in North Carolina, pleaded guilty to election fraud for her solicitation of a foreign contribution to the Trump campaign. Her plea deal allowed her to avoid prison, and included her statement to the judge that should would leave politics for good. Donald Trump’s own sister, Maryanne Trump Barry, resigned from a lifetime federal judgeship in the face of an ethics investigation. Her resignation ended the investigation and may have curtailed any criminal follow up. Perhaps most famously, former president Richard Nixon resigned to avoid impeachment and possible criminal charges, thereby receiving a pardon from Gerald Ford—a tragic, historic mistake.

Santos’s removal deprived him of this opportunity to abuse his office one last time. Early on things looked bleak for him when, despite the likelihood that prosecutors would offer him a plea, he instead dug his heels in angrily characterizing the whole thing as a witch hunt and resisting any call to resign. In a pathetic act of defiance, he asserted that “I will not stand by quietly” and further proclaimed that expelling him “will haunt [Congress] in the future where mere allegations are sufficient to have members removed from office when duly elected by their people in their respective states and districts.” He seems to have missed the point that a great number of his claims during his fraudulent campaign were easily refuted later; many of the statements against him were not mere allegations. Furthermore, as Republican Representative Anthony D’Esposito correctly observed, “Unfortunately, [the voters of Santos’s district] voted for someone who — they didn’t even know who it was. It may as well have been a Disney character, because it wasn’t a real person.” Nonetheless, Santos went on to claim that he would “wear [expulsion] like a badge of honor.” His boisterousness was foolhardy in that it emboldened his detractors, and nevertheless will likely be short lived as his trial comes ever closer. Santos faces more than 20 felony counts, with the initial 13 alone exposing him to up to 20 years in prison. The federal conviction rate averaged across districts ranges above 90% most years; and in 2022 fewer than 1% received acquittals at trial. If Santos goes to trial, he will lose and he will almost certainly face a minimum of a decade in prison.

Only about 2% of defendants charged federally actually take their cases to trial, but that does not mean a pre-trial plea automatically equates to no prison time. No longer possessing his seat in Congress, Santos has little to offer prosecutors in the horse-trade that are plea deals. His co-conspirators already took deals and are almost certainly poised to testify against him, another bargaining chip lost. When sentencing plea deals, federal judges typically follow the federal sentencing guidelines while tracking the terms of the deal made by the prosecutor. Plea deals may lead to a downward departure in the guidelines, which means judges can offer some leniency, but they still routinely end with a defendant serving about one-third of the maximum sentence. In this context, Santos could be looking at a sentence of one-third of 10 to 20 years (3 to 7 years), depending upon the crime to which prosecutors demand he pleads. The sentence could be higher if the judge chooses to deviate upward. Santos’s conduct involved exploiting his Congressional office to commit run-of-the-mill scams, a particularly egregious act. Moreover, given his pugnacity in the process so far, along with the despicable public perception a lenient sentence would engender, it does not seem probable that there will be a lot of sympathy in the plea-deal conference room or before whatever judge oversees the case.

To make matters worse for Santos, the House Ethics Committee released a 56-page report detailing other matters possibly not subsumed by any of the current charges. If further criminal charges arise out of the House’s investigation, Santos’s main concern may well turn toward finding a way to simply avoid dying behind bars. Even if not, should he go to trial and lose on several of the existing counts, his sentence will almost certainly exceed a decade.

Aiding and Abetting

Congress did indeed expel Santos, but over 100 members of Santos’s political party voted against it. The Congress people who decided that their moral virtue required voting against Santos’s expulsion worried, supposedly, that expelling Santos set a “bad precedent.” Rep. Tim Burchett from Tennessee, for example, made a possibly prescient observation in defending Santos when he stated “We’re a bunch of sinners,” apparently implying that all of Congress’s members are criminals. That statement followed a supportive fist bump he gave Santos as he walked into the expulsion vote. Clay Higgins, a Republican from Louisiana mostly known for his bizarre concern about “ghost busses,” opined that the bipartisan House Ethics Committee investigation appeared “weaponized.” Lauren Boebert, a Republican Representative from Colorado mostly known for her soft-porn performance in a public theater, bemoaned “George Santos was elected by New York's Third Congressional District voters and until the day he is actually convicted of a crime, it should have been up to those voters whether or not he remained in Congress.” Former Speaker of the House, disgraced Kevin McCarthy, had previously said something similar, “It’s the voters who made that decision, and he [Santos] has to answer to the voters.” Representative Lisa McClain, a Republican from Michigan, questioned whether all of Congress would “play by the same rules,” noting that recently indicted Senator Bob Menendez has not been expelled.

Although McClain was engaging in partisan whining, she raised an important point. Federal authorities recently charged Menendez with bribery for accepting “hundreds of thousands of dollars of bribes in exchange for using" the senator's "power and influence to ... seek to protect and enrich" his business associates. While Menendez should absolutely be expelled if convicted, there stands a key difference between the two. George Santos won his seat based on the frauds for which he was originally charged. The later charges had to do with him stealing from his own campaign, including stealing directly from donors. Put another way, one could argue Santos was expelled because in some sense he was never actually elected at all. Contrary to Boebert’s failed attempt at acuity, the voters of New York’s 3rd Congressional District did not vote for the Santos that won the seat, and an overwhelming majority has since said so. As I previously noted,

Because the DOJ indicted Santos based in large part on the frauds he allegedly committed to obtain his seat in Congress in the first place, it stands to reason that between now and trial the man simply cannot do the job appropriately or effectively.

Absent an expulsion, the voters would have been left with a Congressman who could not perform the job and, more importantly, a Congressman for whom none actually voted. Moreover, he might have been free to continue stealing from his campaign, his donors, and whatever resources to which serving in Congress gave him access. For once, Congress did the only right thing available under the circumstances. Any member of Congress convicted of felonies should face expulsion. But any member of Congress who defrauds the public to become a member in the first place need not wait for a criminal conviction.

Cell Block C

The example made of Santos at first seems rather odd, however. After all, few appear bothered by any number of other frauds perpetrated on the People of the United States by Congress people, even when those folks dodge punishment for their actions. At the end of his term, Trump abused his pardon power numerous times to relieve many criminal political figures of accountability. Chris Collins was convicted of a variety of charges related to using his Congressional seat to commit insider trading, charges he initially called “meritless.” After his arrest, Collins suddenly decided to rerun for his seat, purportedly to use it as bargaining power for his inevitable plea. Collins called the notion that he re-ran for that reason “laughable,” but then pleaded guilty about a month after winning, His plea immediately followed his resignation from the seat he just won. Collins served 2 months of a still meager 26-month sentence before Trump pardoned him. The federal government convicted Duncan Hunter of corruption for using over $200,000 in campaign funds for personal expenses. Shortly after winning his reelection, Hunter resigned and then pleaded guilty to a reduced charge, which led to a sentence of just 11 months. About eight days before he was supposed to go to prison, Trump pardoned him. Steve Stockman was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison for, among other things, using $1.25 million in political donor funds for personal expenses. After serving just 2 years, Trump commuted his remaining sentence.

The above Congressmen-turned-criminals were all of the Republican party, the same as Santos. In all cases, few if any of their party members called for them to resign, let alone considered expelling them. Collins and Hunter ran for reelection and won after their indictments. Hunter and Stockman specifically stole from their own donors and campaigns. So, why did 105 Republicans vote to expel Santos while hardly making a peep about the quite similar conduct of these others? Some have claimed that the House Ethics Committee’s report served as the “tipping point” because both parties played a role in preparing it. If true, it reveals something about House Republicans’ view of law enforcement when an indictment is not good enough in their eyes, but condemnation proffered by their own party members is. Still, this does not adequately explain taking an action that Congress has done only 6 times in its entire history.

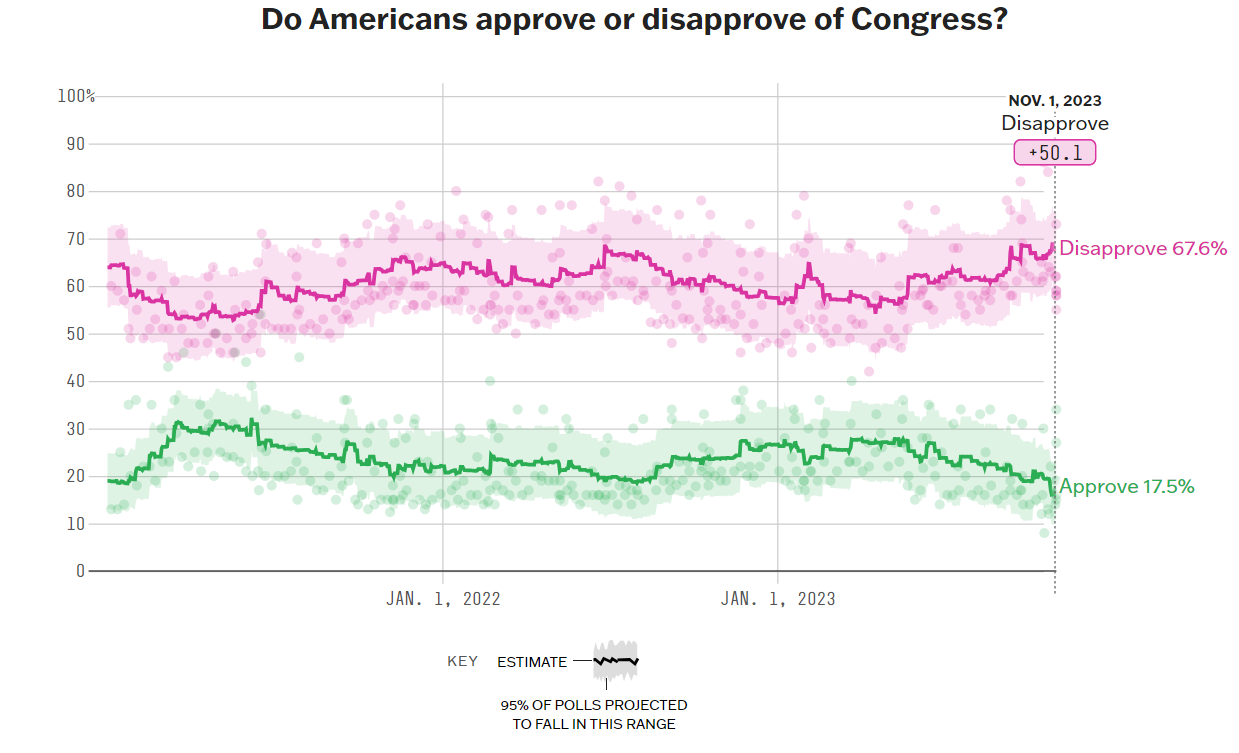

Instead, it seems that this vote had far less to do with most of Santos’s alleged crimes, and more to do with his general conduct. Put simply, even his own party despised him as a person. Santos created a liability for the party incomparable to the other folks mentioned above. Both Collins and Hunter, for example, still won reelection after the accusations against them surfaced. Voters in America generally accept that most of their Congress people are hopelessly corrupt or simply useless, as indicated in polling year-after-year. In Santos’s case, however, the appearance of having stolen his seat by faking who he actually is seems to have tipped the scales against him. Voters made the rare move of organizing protests specifically against him, proclaiming: “On behalf of Concerned Citizens of NY-03, why are we here? Why did we come to Washington? We are here because Speaker McCarthy apparently cannot hear us when we speak from Long Island, so we had to come to Washington to make sure he hears us [demanding Santos’s resignation].” Voter anger heated up rapidly as more accusations surfaced, with nearly 80% of his constituents eventually demanding his resignation. This vitriol arose in part because of the specific content of the lies Santos told. For instance, Santos lied about his mother working at the World Trade Center on 9/11. Protestors were especially perturbed by that as communities in Santos’s district lost many people during that attack. As one Republican voter said, “That’s not funny, to say that your mother was part of that. You have to be really psychologically impaired to throw that around.”

Voters loath Congress. Santos outperformed that disdain. Source: Five Thirty Eight

If the House Ethics Committee report had any influence, it most likely was mere cover to vote to expel a Representative who would assuredly lose the seat in the next election. Representatives Greg Murphy (R-NC), Stephanie Bice (R-OK), and Dusty Johnson (R-SD) all changed their position after the release of the report, for example, attributing Santos’s conduct outlined in it as their reason, despite much of the same conduct appearing in the indictments. The Cook Political Report currently rates Santos’s district as “lean[ing] Democrat” for 2024. By expelling Santos now, Republicans have the opportunity to run a new candidate, giving them a better chance to retake the seat in a typically Republican district. If Santos had remained, it is almost certain he would have lost, thereby flipping the seat to Democrats.

Santos’s conduct also targeted fellow Republicans, provoking anger and organized support for his expulsion. Representative Max Miller of Ohio sent an email to other Representatives outlining how he himself was a victim of Santos’s fraud. He wrote:

Late yesterday on the floor I alluded to a personal impact of Rep. Santos’s conduct. Earlier this year I learned that the Santos campaign had charged my personal credit card – and the personal card of my Mother – for contribution amounts that exceeded FEC limits. Neither my Mother nor I approved these charges or were aware of them. We have spent tens of thousands of dollars in legal fees in the resulting follow up.

I’ve seen a list of roughly 400 other people to whom the Santos campaign allegedly did this. I believe some other of this conference might have had the same experience.

While I understand and respect the position of those who will vote against the expulsion resolution, my personal experience related to the allegations and findings of the Ethics Committee compels me to vote for the resolution. [Emphasis added]

Since I alluded to this on the floor yesterday, and because of the significance of the question before us, I believe you’re entitled to this further explanation for my position.

In addition to defrauding some Representatives of his own party, Santos also threatened any number of them as it became more obvious the expulsion would pass. Just before the vote he warned that an expulsion decision would result in “the undoing of a lot of members of this body.” Santos further claimed he would file ethics complaints against three Republicans who spoke out in support of expulsion, though he did not identify what charges would constitute his complaint. Shortly after the expulsion, Santos effectively provided further fodder in support of the contempt most hold for him. On a livestreamed program, Santos said “They [Congress] all act like they’re in ivory towers with white pointy hats and they’re untouchable. Within the ranks of United States Congress there’s felons galore, there’s people with all sorts of shystie backgrounds.” Who knows what else he may have said about others behind closed doors.

He’s Done

All of this suggests that Santos is toast. He will not beat all the charges, maybe not even any of them. Unlike other cases where political figures saw their convictions overturned on tortured legal logic, Santos’s charges encompass a number of different sorts of conduct, many of them routinely tried and convicted in courtrooms across the country. Moreover, these charges reflect basic, run-of-the-mill theft for which Santos has little or no defense. As such, no appellate court will be coming to his defense like it did for Bannon and others. In addition, no one likes this guy. Republicans hate him for the political destruction wrought to their tenuous and probably soon-to-collapse majority. Some of those same Republicans appear to have been victims of Santos’s theft. His constituents hate him for his lies about sensitive topics like 9/11. Everyone else hates him because he is a petulant, blatant liar, and one symbol of many that illustrates the precipitous decline of American governance. While justice should not turn on the likeability of a defendant, standing alone tarred and feathered in the public eye certainly will not help garner any character letters to give to the sentencing judge.

***

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run a non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

To read more about the corruption of the US Supreme Court click below.