Final assembly of a Boeing 737 airplane, 1975, by Click Americana, CC BY 2.0

Terror at 15,000 Feet

On January 5, 2024, a Boeing 737 Max-9 operated by Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 suffered a mid-flight decompression when a piece of its fuselage dislodged and separated from the aircraft. The incident aircraft was virtually brand new, having taken its maiden flight only in October of 2023.

As the jet climbed out of Portland, Oregon, the door plug on the port side suddenly gave way at around 15,000 feet, sucked out by the extreme pressure differential, leaving a substantial hole in the passenger cabin area. As the pressure between the inside and outside equalized, numerous items ejected from the plane, including a child’s shirt he was wearing at the time and an iPhone that miraculously survived the fall unscathed.

Oxygen masks dropped and the pilots quickly reacted, managing to safely land the aircraft back in Portland with no passengers suffering serious injury. In response to the incident, the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) grounded certain models of the Boeing 737 Max-9.

Photo released by the NTSB shows a gaping hole where the paneled-over door was on Alaska Airlines Flight 1282, following a midair blowout on Jan. 5, 2024. NTSB VIA AP, CBS News.

What is a Door Plug

The piece of the fuselage that ripped away from the plane is known as a “mid-cabin door plug.” A mid-cabin door plug describes a panel with an embedded window fitted into the airframe to replace an emergency door for certain aircraft configurations. An interior panel hides the door plug making it look like any other section of the overall wall.

Airliners must have a certain number of escape doors based on the number of allowable passengers. As airlines can alter the seating arrangement to accommodate their needs, in the instance where they choose to reduce the number of passenger seats, they can also “plug” unnecessary exits to lessen confusion in the event of an emergency evacuation. Both Boeing and Airbus have aircraft that utilize this mid-cabin plug.

At altitudes above 10,000 feet, the chances of a passenger opening a door mid-flight are virtually zero because of the pressure forces on the fuselage. Doors on airliners use cabin pressure to push them against the fuselage where they are stopped by the frame, keeping them securely in place.

In most cases, to open the door one must slide it upward along a short track to bypass the stops built into the frame. Once the stops are cleared, the door swings either out and sideways or out and down, on a set of hinges. In the Alaska Airlines case, had there been a door in the location of the plug, it would have had to have been lifted up a couple inches, then folded down outside of the aircraft.

So, how did this door plug blow off?

Door plugs like the one at issue here use the same mechanism as a normal door, including the same hinge and stop pad arrangement, but differ in that they lack a door handle. Instead, four bolts lock the plug in place to prevent it from moving up (which is the direction it needs to move to open).

There are 12 contact surfaces that press the door against the frame and prevent it from opening—unless it moves upward enough to un-align with those contact points. If the bolts failed (or were never installed), movement of the aircraft could allow the door to slowly shift upward. The creeping misalignment would not likely be noticed by a passenger, even one sitting right next to it.

Once the plug inched far enough up to surpass the stop pads, the interior pressure would forcibly blast it outward, which appears to be what happened here. (Thanks to Mentour Now! for providing a detailed analysis of the mechanics of the door plug.)

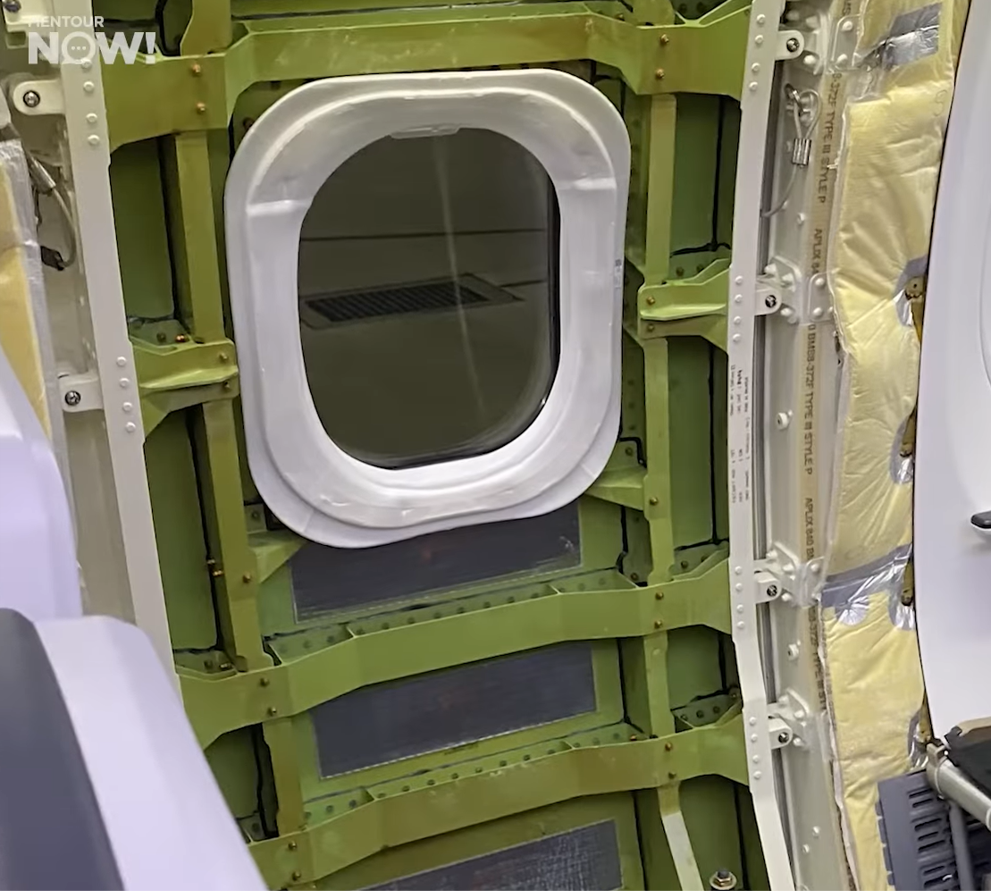

Inside view of a door plug without the interior panel covering.

More 737 Problems?

This incident represents another significant blow to Boeing, which only recently seemed to slink away from even worse news of days past. Back in November 2021, Boeing admitted full responsibility for the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. That crash was the second that happened in a span of just six months; the first occurred in October of 2018 and the Ethiopian crash in March of 2019, both involving the 737 Max-8—the 737 model released before the Max-9. Collectively, those two catastrophes killed 346 people.

In the subsequent investigations, accident investigators determined that chief among the causes was the failure of the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), a software system meant to regulate the pitch of the plane’s nose. On the Ethiopian flight, faulty sensor data tricked the MCAS into believing the plane was pitched dangerously upwards when in fact it was not.

A severe upward facing nose eventually will cause a stall, so the errant data triggered the MCAS to force the plane downward despite the pilots’ efforts to counteract the errant command. Ultimately, the MCAS pushed the flight all the way into the ground, killing everyone aboard.

It is important to understand the sequence of events that led to the Max-8’s problem. In the early 2000s, some of Boeing’s biggest clients considered switching their fleets to Airbus planes because those were more efficient and technologically advanced. To compete against Airbus, Boeing executives made the decision to take the easy way out (and more importantly, the cheaper way) in developing a new jet. Instead of creating a competing model out of whole cloth, Boeing sought to reinvigorate the 737, a plane originally released in 1967.

The Max jets, particularly the 8 and 9, can carry far more passengers than previous models of 737, but require bigger engines to do it. Larger engines would not fit beneath the wing where previous models positioned them. Engineers needed to re-situate them further forward, putting them in front of the wings. Doing so meant that a small portion of the engine sat above the wing line, thereby disrupting the airflow. This caused a destabilization of the flight trajectory in certain circumstances, which is where the MCAS entered the picture.

Forward-placed engines of a larger size caused angle-of-attack problems, so the MCAS provided automated corrections to the plane’s in-flight pitch. Unfortunately, in the case of Lion Air and Ethiopia Airlines, the MCAS performed incorrectly based on erroneous sensor data. Pilot error in responding to the subsequent mistaken directional inputs exacerbated the issue. The pilots are not really to blame, however, as will be made clear below.

Graham Simons, an aviation historian and author of the book Boeing 737: The World’s Most Controversial Commercial Jetliner, said of the Max design:

In my view, the Max was a series of modifications too far. They should have never come out with it in the first place. They should have sat down with a blank computer screen to design an entirely new aircraft.

After the investigation of the two incidents, but prior to its full confession of blame, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) filed criminal charges against Boeing. This was because the airline hid the defects of the MCAS system from their own test pilots as well as those pilots who would later carry passengers. Around the time of the two crashes, sources told the Wall Street Journal:

Boeing test pilots and senior pilots involved in the MAX’s development didn’t receive detailed briefings about how fast or steeply the automated system known as MCAS could push down a plane’s nose…. Nor were they informed that the system relied on a single sensor—rather than two—to verify the accuracy of incoming data about the angle of a plane’s nose.

Of note, relying on a single sensor in commercial aviation is a textbook mistake. The aviation industry thrives on redundancy. Worse than that, Boeing’s secrecy about the effects of the MCAS directly contributed to the Lion Air crash. On this, William Lazonick and Mustafa Erdem Sakinç wrote,

In fact, the Lion Air pilots had no idea that MCAS even existed, and hence could not know that it was the source of the plane's nose-down movement. Prior to the Lion Air crash, Boeing had not documented the functioning of MCAS in its 737 MAX flight manuals.

The DOJ eventually reached an agreement with the company wherein it agreed to pay a fine of over $2.5 billion. The US Attorney’s office said this about Boeing’s culpability:

The tragic crashes of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 exposed fraudulent and deceptive conduct by employees of one of the world’s leading commercial airplane manufacturers… Boeing’s employees chose the path of profit over candor by concealing material information from the FAA concerning the operation of its 737 Max airplane and engaging in an effort to cover up their deception… The misleading statements, half-truths, and omissions communicated by Boeing employees to the FAA impeded the government’s ability to ensure the safety of the flying public.

So, Boeing carries that baggage into the present situation. Immediately following the Alaska Airlines disaster, the FAA issued an emergency airworthiness directive (EAD). According to the FAA, an EAD is “issued when an unsafe condition exists that requires immediate action by an owner/operator.” The EAD prohibited any further flights of the affected model of plane “until the airplane is inspected and all applicable corrective actions have been performed” and approved by the FAA.

Initial inspections immediately following the directive revealed bolts and other hardware parts that did not meet safety standards. United Airlines discovered “installation issues” that led to “some loose hardware” on its own fleet of Max-9s. An airline spokesperson there said, "Since we began preliminary inspections on Saturday, we have found instances that appear to relate to installation issues in the door plug - for example, bolts that needed additional tightening."

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the USA’s agency charged with investigating aircraft incidents, reportedly found the door plug from the Alaska Airlines flight in the backyard of an Oregon home; it was missing four of its bolts. Moreover, the NTSB determined that the accident plane had previously been barred from flying over water because of pressurization warnings received on earlier flights.

Whether the two issues are related has not yet been determined, but they are indicative of problems with the aircraft, or the plug specifically. NTSB investigators noted that all passengers appeared to still be wearing seatbelts (which is required on climb out) at the time of the incident, which prevented anyone from being sucked out of the hole. Luckier still, no one happened to be seated in the row where the blowout occurred. The agency continues to investigate.

What the Heck is Happening at Boeing

Three events in the year from April of 2018 to March of 2019 caused quite a stir in the aviation industry, and nearly destroyed the company. Boeing’s various 737s were long held as the “workhorses” of the skies, sporting an exceptional safety record across millions of flights.

The latest advance, the Boeing 737 Max series, was touted as a highly efficient competitor to the Airbus A320neo, and another success in Boeing’s incredible fleet of 737s. These gushing reviews first changed to worry in April of 2018 when the engine cowling exploded on Southwest Flight 1380, a Boeing 737-700. Shrapnel from the cowling pierced a passenger window and killed Jennifer Riordan. She was partially sucked out the window where she remained until the pilots landed the flight. Suddenly, Boeing found itself and its vaunted 737s under severe scrutiny.

The engine of the Southwest Airlines plane that killed Jennifer Riordan, shown after an emergency landing at the Philadelphia airport, April 17, 2018. - Joe Marcus/Twitter via ABC News.

The year 2018 turned dramatically worse for Boeing with the October Lion Air crash (the first of the back-to-back Max-8 crashes). Quickly following that incident, the FAA issued an EAD. The FAA provided this reasoning:

This emergency AD was prompted by analysis performed by the manufacturer showing that if an erroneously high single angle of attack (AOA) sensor input is received by the flight control system, there is a potential for repeated nose-down trim commands of the horizontal stabilizer. This condition, if not addressed, could cause the flight crew to have difficulty controlling the airplane, and lead to excessive nose-down attitude, significant altitude loss, and possible impact with terrain.

This describes precisely what happened in the Lion Air crash, as well as the Ethiopia incident that occurred just five or so months after the FAA issued its directive. Upon the release of the EAD in November of 2018, many began asking pointed questions about the 737.

After the Ethiopia crash in March of 2019, the public and authorities demanded answers. Indeed, regulators around the world immediately grounded over 300 of the 737 Max-8 jets. Boeing tried to avoid those consequences in the United States, with CEO Dennis Muilenburg purportedly begging then-President Donald Trump not to ground the plane. After some delay, Trump eventually caved to pressure and extended the grounding to US flights. Locking down so many jets led to a roughly $28 billion market loss for Boeing.

For a brief video further explaining the Max-8 saga, click below.

In the subsequent years, Boeing worked to restore its reputation. In 2020 it replaced Muilenburg with a new CEO, David Calhoun. It rolled out the next generation of the 737 Max (the Max-9 involved in the current incident) and saw increasing numbers of deliveries of the aircraft in 2022 and even more in 2023. Business analysts predicted a strong 2024 for the company. Then, Alaska Airlines lost a wall. The depressurization of the cabin of that flight swept out numerous items and simultaneously ripped the veil off of what looks like a continuing trend of issues, ones that Boeing ostensibly believed it had successfully whitewashed.

All Finance, All the Time

FAA administrator Mike Whitaker told media outlets after the Alaska Airlines event that “[w]e believe there are other manufacturing problems” beyond those identified with the door plug, though he did not elaborate on them. Emirates Airlines president Tim Clark said that Boeing has had a pattern of issues going back many years, according to Business Insider.

On the very morning of the Alaska Airlines blowout, Boeing had asked the FAA for a safety exemption for its fleet of 737-700s related to fixing conditions that could compromise the engine housing, like what occurred on Southwest Flight 1380 in April of 2018. The company informed the FAA that its pilots currently follow protocols limiting the use of the engine anti-ice system that could aggravate the defect. Boeing wanted to continue that practice until May of 2026 to implement a full fix. It is unclear if the FAA granted or will grant the request, though the timing of the Alaska incident does not bode well for Boeing.

Kathy Gill, writing for the Moderate Voice, explained in detail how Boeing shifted from making “amazing flying machines” to becoming a mere money pot for greedy shareholders. She wrote,

The Boeing board should have fired ALL C-suite executives by the end of 2020. Instead, the Board made The Blackstone Group/Nielsen Holdings/General Electric alum David L. Calhoun the CEO. (Not an engineer: all finance, all the time.) Calhoun had sat on the board while McDonnell Douglas alumni, financiers not engineers, made decisions that led directly to those 346 deaths [the Lion Air and Ethiopia Airlines fatalities].

Gill further noted that among the questionably ethical decisions Boeing made following the Max-8 crashes, one included replacing 1,000 quality inspectors with “smart tools.” This lack of inspectors may have something to do with the discovery of loose or missing bolts by both Alaska and United Airlines following the latest incident.

Justin Green, an aviation accident attorney at Kreindler & Kreindler, stated that he has concerns based on whistleblower reports about “production pressures and shortcomings in the manufacture of Max airplanes.” He continued, “I think that right now, given the information that these whistleblowers had and what's come out so far, I would just be concerned that the airplane has a manufacturing problem, and it might not be restricted to this plugged door on the Max-9's.”

Former NTSB member John Goglia told FlightGlobal, “It would appear that Boeing needs to seriously increase the number of inspections of the installation of various pieces on their airplanes.” Goglia also pointed out that the door plug itself is not new technology, having been used for years and over millions of flight hours. Michel Merluzeau, an aerospace analyst with AIR, said “we go back to the production challenges that Boeing has been faced with, from a supplier standpoint… also the workforce problems.”

Jon Hemmerdinger of FlightGlobal highlighted other issues related to taking a capitalistic approach to safety. He wrote:

The 737 programme has been beset with hiccups. Last week, news broke that Boeing was urging carriers to inspect 737 Max jets for loose bolts in rudder assemblies. In August, Spirit revealed it had delivered many 737 Max fuselages with potentially defective aft-pressure bulkheads. That issue requires Boeing complete arduous inspections of more than 150 undelivered 737s and forced it to walk back delivery goals.

Some sources have attributed the quality problems partly to errors resulted from less-skilled workers. Boeing hired many new workers recently to replace talented employees lost both to the pandemic and to ongoing retirements.

Hemmerdinger’s last line appears to suggest that some are attempting to blame workers. This may be true to some extent in that Boeing replaced well-paid, highly qualified employees with cheaper, lower skill ones. After all, Boeing has a history of union busting activities, including moving to South Carolina from its base state of Washington. South Carolina’s labor laws favor businesses over workers’ rights. The labor union there accused Boeing of spying and other intimidation tactics against employees who voted in favor of unionization. One worker told the Guardian,

that after the union vote Boeing increased the workload of the group of workers who voted to form a union, reduced quality control and frequently sends the workers job openings in different locations [emphasis added].

Adding to Boeing’s woes, about one week before the Alaska Airlines incident, an employee at Spirit AeroSystems filed an amended class action suit against that company (originally filed in May 2023), alleging that he told company officials about an “excessive amount of defects” in parts the company produces for the Boeing 737 Max.

Spirit AeroSystems is one among several of Boeing’s partners manufacturing various parts for Boeing aircrafts. Many aircraft engineering companies rely on outsource companies like Spirit to reduce costs of production, but this price reduction often comes at the expense of safety. In the class action suit, the Plaintiff asserts, among other things, that Spirit:

…concealed from investors that Spirit suffered from widespread and sustained quality failures. These failures included defects such as the routine presence of foreign object debris (“FOD”) in Spirit products, missing fasteners, peeling paint, and poor skin quality. Such constant quality failures resulted in part from Spirit’s culture which prioritized production numbers and short-term financial outcomes over product quality, and Spirit’s related failure to hire sufficient personnel to deliver quality products at the rates demanded by Spirit and its customers including Boeing [emphasis added].

The lawsuit further claims that Boeing placed Spirit “on probation for multiple years,” which comprised a supposed “last stop” before Boeing would abandon the supplier based on its repeated failures. Spirit faced scrutiny before, for example, when 400 Max jets suffered a delay in rollout because of some defect in certain equipment for the fuselage system produced by Spirit. The complainant in the class action suit states that the company knew of those problems months in advance.

Furthermore, the complaint states that Boeing endured fines by the FAA previously because of Spirit’s inadequate work. In 2019, the year of the Ethiopian Airlines incident, the FAA levied a civil penalty of $3.9 million against Boeing “for installing nonconforming components, provided to Boeing by Spirit, on approximately 133 aircraft. The affected planes were Boeing 737 NG aircraft” (page 12). Just a month later, Boeing received an additional $5.4 million penalty for installing other nonconforming parts on 178 Max jets.

Some experts told the Lever that allegations made in the case against Spirt indicate how big-name manufacturers like Boeing outsource production to save money, possibly compromising safety in the process. Years of “probation” tells the true story; Boeing preferred saving money over concerns about quality, despite knowing about its outsourcer’s deficiencies. As former congressman Peter DeFazio (D-OR) and onetime chair of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure told Jacobin.com, “McDonnell Douglas became the final arbiter, which is now: My stock options and Wall Street have the final say, not the engineers. And that’s how we ended up with a Max.”

Adding to that, economist Mustafa Erdem Sakinç wrote, “Cost-cutting was the single major reason behind selling commercial aircraft-parts operations to . . . the new entity named Spirit Aerosystems.” In the midst of all this, some shareholders submitted a proposal to require that 60% of Boeing’s executives must have “an aerospace / aviation / engineering executive background.” The company rejected it:

because it is impermissibly vague and indefinite so as to be materially false and misleading;

because it would disqualify nominees who will be standing for election as directors; and

because Boeing intends to bring executives whose experiences are best categorized not as “aerospace/aviation/engineering” (however these are defined), but as bringing additional important experience and expertise to the board, in areas such as safety, corporate governance, executive leadership, and risk management.

For Boeing, a background in “aerospace/aviation/engineering” is so devilishly difficult to define that any such suggestion should be discarded. And with the blessing of the SEC under the Trump administration, it was tossed out.

The US government deserves further blame. William McGee, a senior fellow for aviation and travel at the American Economic Liberties Project, said that “Ultimately, the FAA has failed to provide adequate policing of outsourced work, both at aircraft manufacturing facilities and at airline maintenance facilities.” It seems that this time maybe the FAA has finally heard the criticism. On January 12, 2024, the agency announced it will take “significant actions to immediately increase its oversight of Boeing production and manufacturing.”

Notably, Boeing’s CEO David L. Calhoun, appointed in 2020, earned $21 million that year, despite the company suffering a record $12 billion loss and cutting roughly 20,000 jobs. According to the Jacobin Magazine, since 2012 Boeing spent more than $40 billion on stock buybacks and distributed almost $22 billion in dividends to its shareholders—all money which could have, and should have, been spent on safety and adequate manufacturing.

Same Old Story

How many narratives like this will it take to arouse the public against rampant profiteering that leads to quality issues, sometimes to the extent that it puts lives at risk? Boeing seems to have shifted from a focus on preeminent engineering to one of churning out cheap widgets passing as viable products. Unlike the typical mass-produced garbage people purchase every day, however, when manufacturers cut corners on the production of commercial aircrafts, failure results in catastrophes reminiscent of Final Destination movies. All to benefit shareholders and overpaid CEOs.

Indeed, after Boeing fired CEO Dennis Muilenburg following the Lion Air and Ethiopia Airlines crashes, he walked away with a $62 million payout instead of prison time. To give it some credit, the DOJ levied a substantial fine on Boeing for its lawlessness that led to those disasters. Unfortunately, it took the deaths of 346 people to arrive there—and no executive paid the price. Hardly a consolation. And Boeing did not seem to learn its lesson.

Perhaps that has to do with the fact that it showed only two profitable quarters between the grounding of the Max jets in 2019 and the end of 2022, even though its executives continued to rake in millions. In a world where shareholder dividends and CEO avarice mark the only directives on corporate behavior, is anyone surprised a door blew off at 16,000 feet because of some loose nuts?

If you enjoyed this article, consider giving it a like or Buying me A Coffee if you wish to show your support.

You would think all Boeing employees would have a background education in aviation.. well time for new plane design.