Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

In prosecuting a criminal case some years back, our defendant—charged with bribery and other crimes—managed to delay the proceedings numerous times. On at least one occasion (maybe more, I don’t remember), he filed a motion to reargue that the court granted. A motion to reargue allows parties to relitigate a decision already reached by the court—an exceedingly unusual occurrence. Indeed, my partner—who had investigated homicide cases for well over a decade before then—confessed he had never even heard of such a motion, indicating how infrequently they are filed, let alone granted. The defendant in our case had a seemingly endless bucket of money to support his defense, whereas the accused killers my partner routinely helped prosecute typically did not. It was a stark reminder of the leverage money and influence buys in the criminal justice system in the US.

Just recently, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) agreed to hear former president, and accused criminal, Donald Trump’s claim of presidential immunity. In short, Trump requested the court to accept that he enjoys “absolute immunity” from prosecution for federal crimes committed while in office. The District of Columbia Court of Appeals roundly rejected Trump’s argument, writing:

The separation of powers doctrine, as expounded in Marbury and its progeny, necessarily permits the Judiciary to oversee the federal criminal prosecution of a former President for his official acts because the fact of the prosecution means that the former President has allegedly acted in defiance of the Congress’s laws. Although certain discretionary actions may be insulated from judicial review, the structure of the Constitution mandates that the President is “amenable to the laws for his conduct” and “cannot at his discretion” violate them.

This conclusion of law (should have) surprised no one after the oral arguments on the matter. During those proceedings, Trump’s lawyer propounded the notion that a president could not be prosecuted for ordering Seal Team Six to kill his political rival unless, and until, the Congress impeached and convicted him. The absurdity of the argument effectively destroyed any weight that might have remained among his other contentions. Upon the District Court making its ruling, the law on the matter was largely settled—no other circuit has interpreted the claim any differently (no other circuit has considered it at all) and now at least two courts have reached the same conclusion of law.

Nevertheless, SCOTUS took the case. In its brief order, here is how the Court situated the question it plans to consider:

Whether and if so to what extent does a former President enjoy presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for conduct alleged to involve official acts during his tenure in office.

The SCOTUS entertains almost all cases for one of three reasons: there is a circuit split, an open constitutional question, or on a vote by 4 or more justices on a writ of certiorari. The last of these, the writ of certiorari (pronounced: sir-she-yor-ee), is the method by which SCOTUS took this case. Notably, this is the rarest way by which a case comes before the Court. Even among writs submitted wherein an injustice might lead to the wrongful execution of a prisoner, the Court almost never hears them. Indeed, since 2020, it has granted only two stays for this reason. Moreover, the SCOTUS has shown a general irritation with receiving ‘true justice’ criminal cases at all. Neil Gorsuch openly complained that challenges to the death penalty comprised “unjustified delay[s].” Gorsuch, along with Clarence Thomas, even went so far as to propose “a radical shrinking of federal habeas corpus relief for state prisoners who are in custody pursuant to a final judgment of criminal conviction. They called for a return to the supposedly traditional principle that federal courts cannot grant habeas relief to such prisoners unless the state court that sentenced them lacked jurisdiction.” Within this framework the Court still granted Trump’s writ. Upon its declaration to hear Trump’s immunity claims, legal scholars and commentators rushed to the airwaves and web to criticize or otherwise speculate on the Court’s motives. There are arguments from those who see this as intentional interference in the schedule of Trump’s criminal cases, while others find some rationality behind the decision.

The case arrived in front of SCOTUS weeks ago when Special Counsel Jack Smith (who is prosecuting Trump) filed a request for the Court to let stand the DC Appellate Court’s holding so his criminal case could move forward. Smith filed the expedited request in response to Trump’s own filing around that time seeking a higher judicial review on the immunity claim. In agreeing to hear Trump’s argument and granting a stay (a pause) in the criminal proceedings, the SCOTUS likely delayed Trump’s criminal trial both in DC and Florida by weeks, if not months. The court ordered an “accelerated” briefing on the case (some SCOTUS cases take months or years to move through the entire process), but as Stephen Vladeck and Dahlia Lithwick point out, SCOTUS has heard many monumental cases with far more alacrity than indicated in this one. One of those swift-moving cases involved a president accused of crimes, another involved deciding an election. Lithwick and Vladeck also note that just a few months ago, the Court heard and decided an abortion case in a total of about seven weeks. Nonetheless, they find reasonable arguments for and against whether the current situation suggests a willful intent by the Court to delay Trump’s prosecution:

There are good arguments for why the court ought to be moving faster in these political emergency appeals. But it’s worth emphasizing that, much as we don’t like them, there are arguments on the other side, too — for why the court ought not to be moving even this fast. Trump didn’t even ask the court to take up his appeal when he sought to keep the prosecution on hold; the court did that for him. And there have been some vocal commentators with no love lost for Trump, like Harvard law professor Jack Goldsmith, who have suggested that the court could and should not decide the case on an expedited schedule — where it wouldn’t get briefed or argued until the term that starts in October.

Thus, it’s worth at least indulging the possibility that the court’s action on Wednesday was a least-worst compromise — one that for the moment united the justices who would have kept the January 6 prosecution on hold indefinitely with those who didn’t want to take it up in the first place.

Randall Eliason, who teaches at George Washington University Law School, stated “My best guess is that they don't want to leave the impression that there's never any presidential immunity under any circumstances and they want to write something more nuanced.”

These commentators are not alone. Stephanie Jones, a lawyer who had advised the January 6 committee investigating the insurrection, writes that had SCOTUS elected not to take the case, it “would not have made Trump’s immunity claim go away or clear the way for him to be held accountable.” Jones argues that without the finality of a SCOTUS decision, Trump could simply assert the immunity argument in his other criminal cases, effectively delaying them all one-by-one. Only the DC case would have potentially proceeded as normal. This is probably true, though SCOTUS accepting the case and framing the legal question as it has does not necessarily preclude the possibility that Trump will assert variations of the immunity argument in those jurisdictions regardless, thereby delaying each. It will depend on the Court’s ultimate ruling.

Michael Popok, of the Medias Touch Network, a long-experienced attorney, like Eliason believes that SCOTUS may wish to bring some clarity to presidential immunity and official acts to try and settle the issue once and for all. Popok theorizes that SCOTUS may incorporate some of the DC Court of Appeals’ decision to declare that 1) former presidents cannot invoke blanket immunity, and 2) the president does not have a role in elections and therefore interference in them is not an official act. Popok’s pontification is interesting in that it positions SCOTUS in such a way to concretize the necessary elements for immunity to apply. If he is correct, it would forestall appeals by Trump related to any acts that tended to or did interfere in the election process. It would also eliminate any immunity argument in the Florida case because the charged conduct there occurred when Trump was a former president.

Popok’s analysis is supported by SCOTUS precedent. In the now-infamous McDonnell case, here is how SCOTUS defined an “official act”:

any decision or action on any question, matter, cause, suit, proceeding or controversy, which may at any time be pending, or which may by law be brought before any public official, in such official's official capacity, or in such official's place of trust or profit.

This definition cannot alone concretely answer whether Trump calling Georgia officials to “find votes” constitutes an official act without further factual analysis. In other words, Trump could nonetheless file an appeal in Georgia hinging on whether his call to the governor there fell within the definition outlined in McDonnell. But the case did not end there. In vacating the McDonnell conviction, SCOTUS wrote that a call itself generally does not constitute an official act. It wrote:

The first inquiry is whether a typical meeting, call, or event is itself a "question, matter, cause, suit, proceeding or controversy." The Government argues that nearly any activity by a public official qualifies as a question or matter — from workaday functions, such as the typical call, meeting, or event, to the broadest issues the government confronts, such as fostering economic development. We conclude, however, that the terms "question, matter, cause, suit, proceeding or controversy" do not sweep so broadly.

Applying that same approach here, we conclude that a "question" or "matter" must be similar in nature to a "cause, suit, proceeding or controversy." Because a typical meeting, call, or event arranged by a public official is not of the same stripe as a lawsuit before a court, a determination before an agency, or a hearing before a committee, it does not qualify as a "question" or "matter" under § 201(a)(3).

Theoretically, Trump could still appeal on the grounds that his call to Georgia officials was to address a “question” or “matter,” but the odds do not seem in his favor. The Northern District Court of Georgia examined what constitutes official acts (albeit under a separate but similar statute) as it pertained to one of Trump’s codefendants: “To satisfy the [scope of federal office] requirement, the officer must show a nexus, a causal connection, between the charged conduct and asserted official authority.” What followed was a detailed exposition of the facts, and then a holding that Meadows’ activities fell “outside the scope of [his] federal office.” The District Court’s opinion does not help Trump and, if Popok is correct in his prediction about the way SCOTUS might situate its holding, the McDonnell and Meadows cases combined suggest Trump will definitively lose. A lot depends on how SCOTUS proceeds.

Despite all this, some are less convinced. Michael Luttig, a former federal judge widely described as “conservative,” told MSNBC “There was no reason in this world for the Supreme Court to take this case.” Michael Waldman, president of New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, described the Court’s decision to take the case this way: “It’s slow-walking. There’s very few other ways, in my view, to interpret it. This appears to be the approach that helps Trump the most while appearing not to.” Richard L. Hasen wrote for Slate that Trump’s indictment in the DC case for election subversion “is perhaps the most important indictment ever handed down to safeguard American democracy and the rule of law in any U.S. court against anyone.” He then later told the Washington Post “And now it may not happen because of timing, timing that is completely in the Supreme Court’s control. After all, this is the second time the Court has not expedited things to hear this case.”

There are two distinct viewpoints here. One is that the highest court in the land is ostensibly going against its own principles that oppose delaying criminal trials, to hear a case for which there is no lower court dispute of law, to adjudicate an issue that may be limited to facts specific to one case, which will delay the “most important” criminal case in US history. The other is that SCOTUS wants to address this unquestionably novel issue of law and set a concrete precedent for future courts. Given that SCOTUS’s extensive corruption grows by the day, it is objectively fair to harbor concern over its motives. Whether the Court acts reasonably and fairly remains to be seen, and if it missteps it will solidify the growing opinion that it is irredeemable. However it unfolds, it is not just SCOTUS that is contributing to the vast appearance of impropriety in the justice process related to Trump.

At the lower-court level, Trump has repeatedly enjoyed treatment rarely, if ever, bestowed upon other defendants. Danya Perry, a former federal prosecutor and now a defense lawyer, told Huffington Post:

Most defendants who enter the federal criminal justice system do so with a knock and a warrant at 6 a.m.; handcuffs and possibly shackles; removal of cell phones, belts, shoelaces and wallets; mug shots and fingerprints; and some form of bail package. They also face serious consequences if they issue threats or tamper with witnesses once released.

Trump has faced virtually none of that. Despite having the eminent ability to flee, he was not forced to hand over his passport. He had a mugshot taken in only one of four jurisdictions where he has been arrested. In Georgia, where that mugshot was taken, the burden is on defendants to prove that they do not pose a risk to witnesses for them to receive bail. By the time of his booking Trump had already made many intimidating statements about witnesses against him, yet the court there did not require him to prove that he is not a threat to them. And, he has even violated the only three conditions imposed upon him in the federal court in Florida. Those are:

Appear in court when required;

Do not break any laws; and

Do not communicate about the facts of the case except through counsel.

While under those provisions, Trump repeatedly threatened judges and their staff, prosecutors and their staff, and even witnesses against him. These are all crimes. Impactful crimes. In one of Trump’s civil cases, for example, the judge determined the circumstances to be so severe that he felt the need to warn jurors not to reveal their identities or risk facing “harassment and threats of violence from Trump supporters.” All of this while Trump faces 91 criminal counts for trying to overthrow an election, stealing highly classified documents, defrauding voters in New York, among many other things. It is inarguably absurd that he has not been held until trial in at least one of these jurisdictions, if the justice system followed its own standards and precedents.

Compare the treatment of Trump to others who have engaged in similar conduct, but do not have the luxury of wealth or influence. Remember, Trump is accused of illegally taking, possessing, and possibly sharing more than 300 classified documents—5,100 pages—and has not faced a day in a holding cell, let alone prison. Reality Winner was arrested, held without bail until conviction, and sentenced to more than five years in prison for taking a single classified document. Jack Teixeira was also charged with stealing classified information. FBI Director Christopher Wray in a press conference on Teixeira’s case told media, “Individuals granted security clearances are entrusted to protect classified information and safeguard our nation’s secrets. The allegations in today’s indictment reveal a serious violation of that trust.” Acting U.S. Attorney Joshua S. Levy said, “The unauthorized removal, retention, and transmission of classified information jeopardizes our nation’s security.” Teixeira sought to be released pending trial for the same reasons that Trump is currently free, but the court denied his request calling him a “flight risk” and “warning that a ‘foreign adversary’ could try to help him escape the country.” Here are 11 more examples of prosecutions with similar facts, but very different treatment of the defendants.

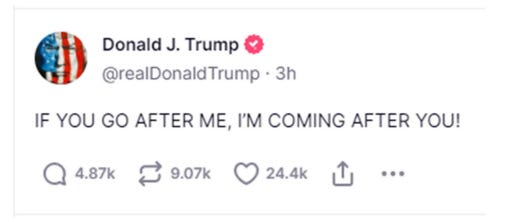

In a case in West Virginia, a man was charged with “terrorist threats” after he purportedly told correction officers that he would kick a certain judge in the balls and then “whip his ass.” A day after Trump pled not guilty to charges of attempting to overturn the election, he posted “If you go after me, I’m coming after you!” on his social media.

On another occasion, Trump posted a photo of himself holding a baseball bat while facing the direction of the New York prosecutor in charge of his case.

When it caused a firestorm, Trump offered a rather pathetic defense.

They put up a picture of me, and you know, where I was holding the baseball bat, it was at the White House. Make America, Buy America. Because I did a lot of Buy America things and this is a company that makes baseball bats. I didn’t do it, they did it. I guess the people that do the paper or somebody put pictures together. But I was holding the baseball bat in order to promote ‘Made in America’.

His vapid response notwithstanding, Trump posted the image that included District Attorney Alvin Bragg, whether he crafted it or not. The 2nd Circuit, in US v. LaFontaine, restated its position about witness intimidation and disrupting legal proceedings that it first articulated in the criminal trial of famous mobster John Gotti:

[W]e held that a single incident of witness tampering constituted a “threat to the integrity of the trial process, rather than more generally a danger to the community,” and was sufficient to revoke bail. The Gotti court reasoned that pretrial detention was even more justified in cases of violations related to the trial process (such as witness tampering) than in cases where the defendant's past criminality was said to support a finding of general dangerousness. Although witness tampering that is accomplished by means of violence may seem more egregious, the harm to the integrity of the trial is the same no matter which form the tampering takes. [emphasis added]

In the LaFontaine case, the court found the defendant to have violated her bail provisions by engaging in the following conduct: (1) contacted a government witness in direct violation of the district court's order; (2) there was probable cause to believe that [the defendant] made materially false statements in her affidavits to the court; and (3) there was probable cause to believe that [the defendant] committed the crime of witness tampering under 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c)(2). Both the district and appellate court found the revocation of bail lawful based on the defendant’s violation of imposed conditions of release, and on the inability to prevent the defendant from continuing those violations—other than sending the defendant to jail. Furthermore, the court required only a finding of probable cause, a much lower standard than beyond a reasonable doubt. Trump has repeatedly violated the conditions of his release and there is sufficient probable cause to believe he intended to intimidate witnesses.

He is getting special treatment, plain and simple

Christopher Robertson and Russell Gold, both lawyers, note that Trump has been coddled from the beginning. They point out that three-quarters of federal criminal defendants are locked up while awaiting trial. Trump has beaten those odds twice now, amidst two separate federal indictments in two different jurisdictions. His legal team has been awarded numerous delays, another benefit rarely given to defendants. Robertson and Gold suggest one reason why:

Prosecutors’ decision to treat Trump differently from other criminal defendants could serve a few purposes.

The Justice Department is prosecuting a former president. That puts the department in a delicate, high-profile position, where it has the “Herculean task of putting an ethical rope through a needle,” as one former federal prosecutor has said.

This seems to underscore the point that the higher one’s level of influence is, the more unfair the system of justice in the United States becomes. This applies not just to political figures. Elon Musk, after all, rather than face a litany of charges for his long well-documented history of crime, instead remains the preferred contractor to the US government despite frequently engaging in conduct that likely contradicts the government’s own policies. All too often, rich or powerful people escape facing justice, no matter how public their crimes. Wherever one falls on the political spectrum, repeating Trump’s claim that he is being treated unfairly to his detriment is engaging in disingenuousness or ignorance. While it is true he is being treated differently, the unfairness belongs to everyone else.

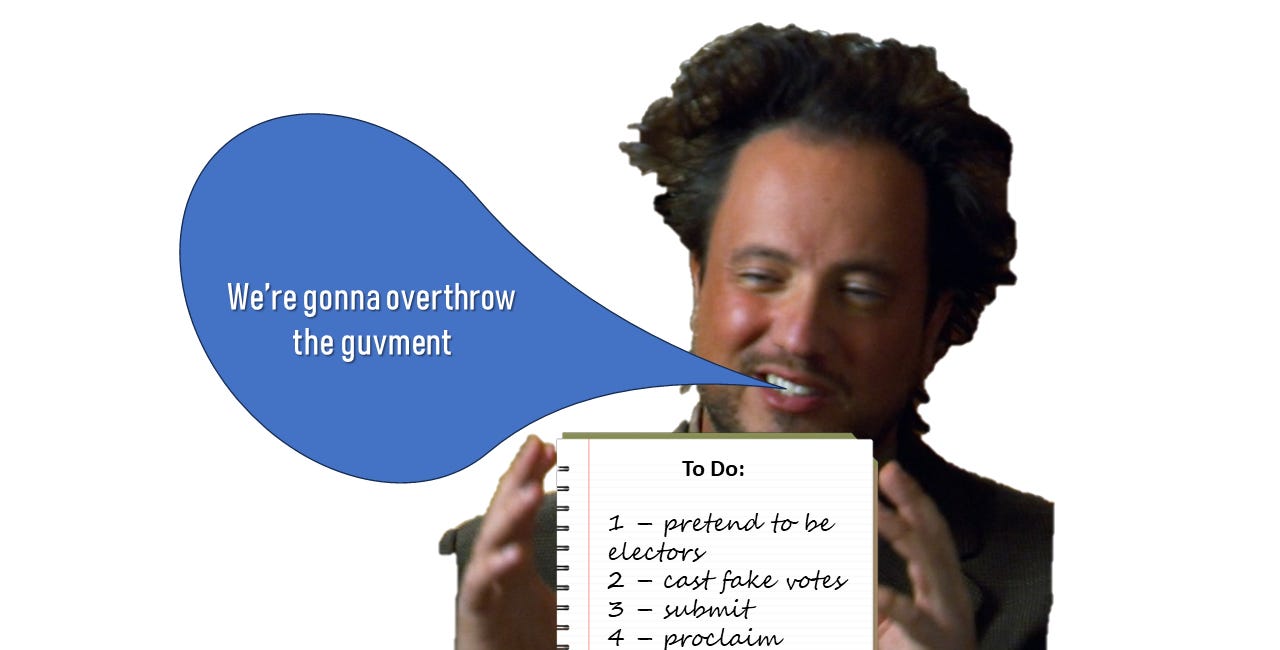

To read about one prong of the massive conspiracy Trump is charged with coordinating, click below.

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run the EALS Global Foundation non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.

Sometimes the bad guys win.. I'm sure there are others that SCOTUS's have helped, even prior to the current judges.

We wait and see 🙈