Abandoned in Africa

Despite promises from the wealthy, Africa is largely forced to fight climate change alone

Visit the Evidence Files Facebook and YouTube pages; Like, Follow, Subscribe or Share!

Find more about me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or Mastodon. Or visit my EALS Global Foundation’s webpage page here.

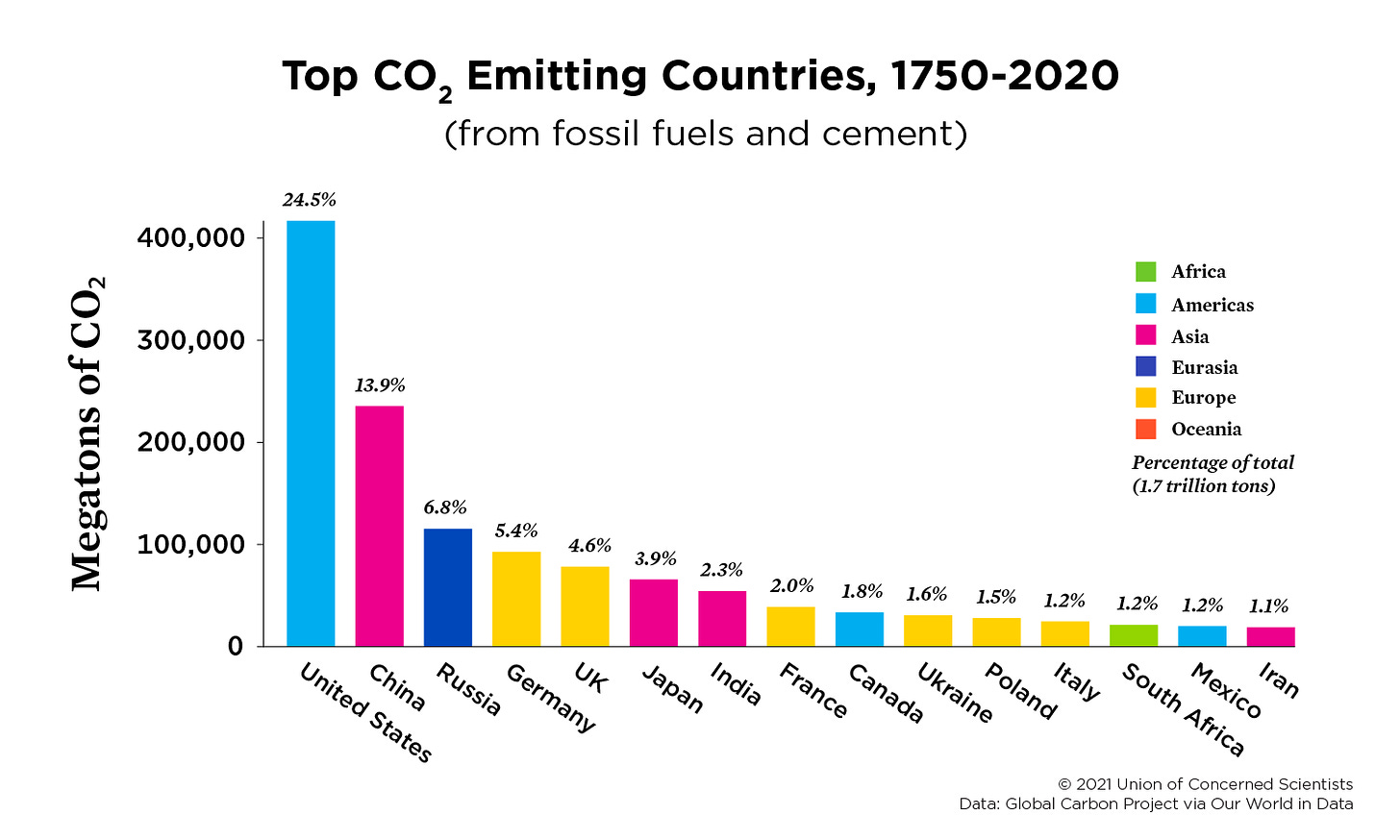

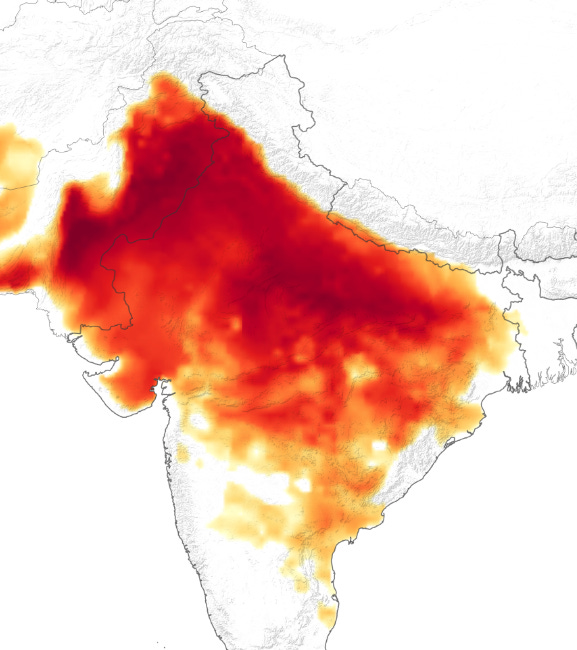

When it comes to climate change, Africa has gotten a raw deal. Despite contributing less than 4% of global emissions, it has suffered perhaps the most from the negative effects of climate change. In 2020, wealthy nations admitted that they had failed to meet their self-imposed annual goal to provide financing to countries vulnerable to climate change. As a result, African nations currently suffer water scarcity and climate-driven displacement; millions face starvation because of changing weather patterns destroying the agricultural cycle; eighty-six million people will be forced to migrate by 2050; thirty-five percent of deaths from extreme weather happen in Africa; and over 100 million people face or already endure extreme poverty. Kaveh Madani, an environmental scientist at Yale and Imperial College London, sums it up this way:

White scientists sit in their ivory towers in the west and prescribe solutions for Africa, so people can be happy at the end of the century. Black scientists are trying to cope with the absence of resources, so Africans can live today… It’s not about ‘I am saving you’, it’s actually about [saying] I’m responsible for setting your house on fire.

In October 2022, Assistant Secretary-General for Africa, Martha Ama Akyaa Pobee, told the UN Security Council, “Africa, the continent with the lowest total greenhouse gas emissions, is seeing temperatures rising faster than the global average.” After elucidating various projects happening to try to mitigate climate change there, she concluded, “Our response today does not match the magnitude of the challenge we are facing.” As Peter Muiruri wrote in the Guardian, “Africa is talking but is the west listening?”

The answer seems to be ‘not really.’ Maimoni Ubrei-Joe, a climate justice and energy program coordinator at Friends of the Earth Africa, stated:

What should be Africa’s focus now is to stop the contributors to climate change at source and not look for shortcuts to keep extracting using the smokescreen of the carbon market, geoengineering and other false solutions. This Nairobi Declaration is short of these ideas and it could just be another beautiful document heading for the shelves.

In September 2023, at a convention in Kenya, where the Nairobi Declaration was ratified, the climate envoy to the United States, John Kerry, said “The words come easily. The actions seem to be a bit more difficult. Africa is meeting. Africa is talking. Africa is deciding.” The people of Africa face the hard truth that wealthy nations do not have any real interest in mitigating the problem. One need only look at the actions applicable to their own countries. In Africa, the tradition is and has historically been to extract whatever value can be obtained and to dangle greenwashed ideas in compensation. In light of this, many there are taking on the challenges themselves.

Source: ucsusa.org

Ethiopia

In 2020, only 50% of the population in Ethiopia had access to the country’s electrical grid. Currently, Ethiopia generates 90% of its power from hydroelectric projects. Unfortunately, its seminal project, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), ongoing for 12 years now, is rife with controversy. Egypt and Sudan have complained that the project will reduce their water supplied by the Nile River that GERD will dam. Talks in 2023 among the three countries did not come to any resolution. Perhaps in response to the unpredictable trajectory of that project, the country recently signed an agreement with United Arab Emirates' AMEA Power to build a wind farm capable of generating 300 megawatts. In addition to wind energy, Ethiopia and Kenya also received a $35 billion investment in November 2023 to bolster their geothermal energy production. The project is expected to produce 90% of Africa’s geothermal production (13 GW) by 2050. If the extraction is conducted properly, geothermal energy has very limited environmental impact. The Ethiopian government is looking to commence up to 17 more geothermal projects, targeting the generation of an additional 35,000 MW.

In January 2023, the country signed an agreement with another UAE company, Masdar, to develop a solar project generating up to 500 MW. In June 2023, the World Bank provided financing for 20 solar minigrid solar projects. The bidding stage closed August 15, 2023. Rural communities will be the primary focus of these minigrid installations. Chinese company Sinosoar won the bid and claims that when complete the project will supply power to more than 20,000 rural Ethiopians.

Kenya

As noted above, Kenya and Ethiopia received a large investment in their geothermal industry. Geothermal and wind energy provide a substantial portion of Kenya’s energy. It continues to struggle, however, with stability in its grid. Recently, the African Development Bank and Japan combined to invest $420 million into improving Kenya’s transmission lines, which is key to reducing the regular blackouts citizens endure. This is part of its ambitious goal of reaching 100% clean energy by 2030. As of 2021, the country already produced 81% of its energy from low carbon sources.

While bolstering its geothermal production, Kenya also has ramped up its wind energy sector. Its Lake Turkana Wind Plant (LTWP) produces 310 MW. Consisting of 365 wind turbines, the complex supplies 17% of the country’s power. The Kipeto Wind plant generates 100 MW. Located southwest of Nairobi, the plant sits right in the middle of the migratory path of numerous bird species. Watchers such as Joseph Mureesi can shut down any number of the 60 turbines within a minute to accommodate passing flocks. Other projects remain at various stages of bidding or development, helped along by its 2019 Energy Act, which makes the country very amenable to outside investors.

Morocco

As of 2021, Morocco produced around two-fifths of its energy by renewables. In 2019, it launched the world’s largest concentrated solar farm. Positioned in a relatively deserted region on the border of the Sahara Desert at Ouarzazate, the complex produces 580 MW. The project is more fascinating than a mere field of solar panels: “Every few minutes, the mirrors rotate to better direct sunlight towards tubes full of synthetic oil, making it so hot, it turns into vapor. A turbine uses the vapor to produce enough power for 1.3 million people.” Ghalia Mokhtari, a lawyer and energy specialist with the Moroccan Institute of Strategic Intelligence, noted that Morocco enjoys the benefit of among the highest “solar radiance and wind levels” in the world.

The country released an updated climate pledge to the UN in June 2021, promising to reduce its greenhouse emissions by 17-18% by 2023. Along with the solar project at Ouarzazate, Morocco also hosts the Tarfaya wind farm. Located in southern Morocco, the wind farm contains 131 wind turbines that generate 2.3 MW each. In total, it outputs 100 GWh per year. Every watt of power is sold to Morocco’s National Office of Electricity and Drinking Water, providing power to 1.5 million Moroccan households. Tarfaya wind farm is the largest wind-producing complex in all of Africa.

By 2030, Morocco intends to generate 52% of its energy from renewables, and 80% by 2050. Part of the plan to do so requires phasing out dirty energy sources, such as coal. Right now, coal generates about two-thirds of the country’s electricity. In 2021, the government laid out a plan to phase out 2,400 MW of coal-generated electricity by replacing it with natural gas. In addition, increased attention and funding have been given to climate resilience research, reduction, and prevention. It implemented its Monitoring and Coordination Centre to manage growing numbers of climate-change-driven disasters. This is part of its larger Morocco Integrated Disaster Risk Management and Resilience Program, funded partly with assistance by the World Bank, which seeks to redesign the country’s planning for, response to, and mitigations of disasters in the country.

Nigeria

Nearly 71% of the population of Nigeria lacks electricity, despite it having the largest economy in Africa. Its economy benefits from the fact it is the largest producer of oil and natural gas in Africa. The World Economic Forum produced a paper in which it noted that off-grid, standalone solar distributions increase at an average of 22% per year. These are bringing electricity to growing numbers of people in rural areas. In November of 2023, the Union Bank of Nigeria and Germany's DWS Group signed a memorandum of understanding seeking $500 million in investment in green energy products, primarily in rural areas. Under the country’s Electricity Act 2023, the country plans to convert 30% of its energy production to renewables by 2030. This includes promoting waivers, subsidies, and financial incentives to encourage development in these kinds of projects. It also opens channels of communication between the private sector and government. In 2019, Nigeria emitted more greenhouse gases than every other country in Africa except South Africa. Since then, it has passed its Climate Change Act, released its “long-term vision” in accordance with its commitments under the Paris Agreement, and implemented its 2022 energy transition plan. While these documents indicate a willingness and desire to transition to cleaner energy, the process for doing so remains stalled, partly due to finances and the economic impact of shifting away from oil, but also because of politics and related issues. Nevertheless, the situation contains some promise for success.

Egypt

Egypt announced its 2023 strategy focused upon a variety of measures to improve the country’s carbon footprint. Among these, it set a target of 42% renewable energy by 2030. The Electricity Law No. 87 of 2015 and its subsequent amendments have opened the door for easier investment in the renewable energy sector. Solar plants generated 4,500 GWh, while wind farms reached 5,400 GWh, and hydropower produced 14,000 GWh in 2021. Saudi Arabian firm ACWA Power signed a memorandum of understanding in 2022 to build a 10 GW wind farm that will supply power to 11 million households. Helped by financing from the World Bank, the Agence Française de Développement (AFD), and the European Union (EU), Egypt expanded electricity access to 2.25 million additional households between 2014 and 2022. The Egyptian Minister of Electricity and Renewable Energy’s Dr. Mohamed Shaker, announced in October 2023 that a Belgian consulting firm was working with the electric authorities to outfit Egypt’s transmission network to accommodate 126,000 MW of renewable energies in the next few years.

Zimbabwe

In 2015, Zimbabwe committed to reducing its emissions by 33% by 2030. The country currently contributes less than 0.1% to global emissions, but has nonetheless committed to achieving 16.5% of its overall electricity supply from renewables. According to its 2019 National Renewable Energy Policy, Zimbabwe produces a capacity of 2,300 MW, supplying 42% of its population. From 2017 to 2030, it plans to increase its hydropower output from 5% to 27%. Just days ago, Optate Africa sought a 25-year lease of 100 hectares of land in the southwest corner of the nation. Its goal is to construct a 200 MW wind-power plant, which would increase the nation’s electricity output by nearly 10%. In March of 2023, the state-owned electricity distributor signed a memorandum of understanding with France’s HDF Energy to build the country’s first green hydrogen power plant. The plant is expecting to produce up to 178 GWh of power upon its completion. In December of 2022, Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube announced that the country would offer up to $1 billion in incentives to promote the production of 1,000 MW via solar power. The country has faced significant inflation and currency problems, so it is ramping up efforts to attract foreign investment to speed up its renewable transition process.

South Africa

In 2011, South Africa initiated its Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Program. The program aimed to bring “additional megawatts onto the country’s electricity system through private sector investment in wind, biomass and small hydro, among others.” Since then, nearly $11 billion has been invested in the sector leading to more than 6.2 GW of power generation, over 11% of the nation’s total. One such example is the Eskom Just Energy Transition Project (EJETP), which seeks to decommission the Komati coal plant and repurpose it with renewable energies. This is a big step because South Africa is the largest coal-based energy producer in Africa. As of mid-2023, the country only produced 13% of its energy from renewable sources. Such a small amount reflects the challenges of some countries’ transition to cleaner energy. In South Africa, many assert that the core issue lies in mismanagement of its largest power producer, Eskom. Whether it can continue toward its goal of replacing 12 GW with cleaner energy remains to be seen. A key problem is that the coal industry employs more than 120,000 people, but the aid offered has come in the form of loans rather than direct aid. Analysts suggest that this needs to change if the green energy transformation will succeed.

Conclusion

Africa contributes the lowest per-capita volume of climate change-causing emissions of any populated continent in the world. Yet, it faces some of the most severe affects. Having endured colonialism, resource theft, and economic repression for centuries, nearly every country on the continent lacks sufficient resources to fully implement change on its own. Many countries have engaged in creative, diplomatic efforts to forward their own development of greener energies, as the above examples show. Nevertheless, the world needs to increase its commitments and, more importantly, its funding to African countries engaged green transitioning. After all, the economic and societal impacts on the continent are due in very large part (arguably at least 95% of it) to the actions of so-called developed nations that continue to pollute and to support polluters with impunity.

For more on how climate change has particularly devastating impacts on specific regions, click below.

I am a Certified Forensic Computer Examiner, Certified Crime Analyst, Certified Fraud Examiner, and Certified Financial Crimes Investigator with a Juris Doctor and a Master’s degree in history. I spent 10 years working in the New York State Division of Criminal Justice as Senior Analyst and Investigator. Today, I teach Cybersecurity, Ethical Hacking, and Digital Forensics at Softwarica College of IT and E-Commerce in Nepal. In addition, I offer training on Financial Crime Prevention and Investigation. I am also Vice President of Digi Technology in Nepal, for which I have also created its sister company in the USA, Digi Technology America, LLC. We provide technology solutions for businesses or individuals, including cybersecurity, all across the globe. I was a firefighter before I joined law enforcement and now I currently run the EALS Global Foundation non-profit that uses mobile applications and other technologies to create Early Alert Systems for natural disasters for people living in remote or poor areas.